Rocky Marciano was a slow, stocky kid, with short arms and stubby legs. He wasn’t the kind of kid you’d pick to one day be an elite boxer, yet he went on to become the only undefeated heavyweight champion in boxing history. In the process, Marciano became a cultural icon in 1950s America, rubbing shoulders with presidents, movie stars, and gangsters.

How did someone who got a late start in the sport, become one of boxing’s greatest athletes? And what happens to a man when fame and fortune are suddenly thrust upon him?

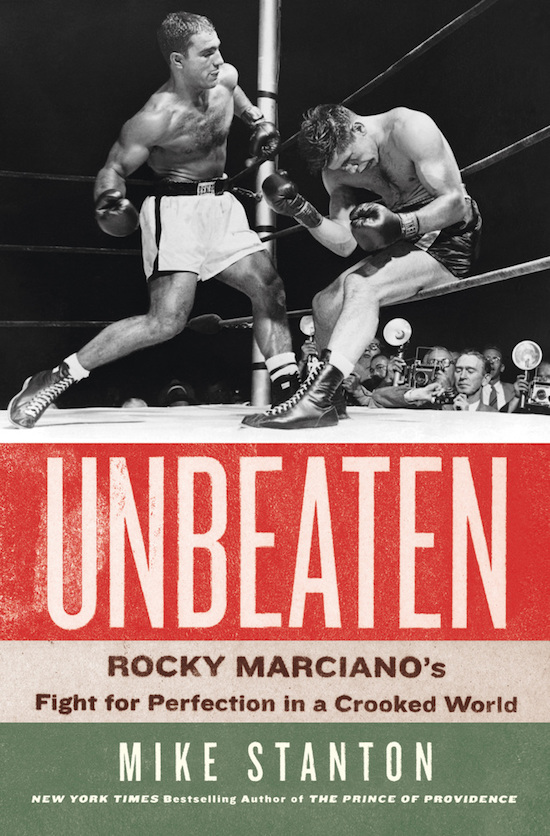

My guest today explores those questions in his new book Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a Crooked World. His name is Mike Stanton and today on the show Mike shares how grit, discipline, and fate led Rocky to become the only undefeated heavyweight fighter in boxing history. Mike then shares the challenges Rocky faced with his newfound fame — from balancing work and family, to managing a huge influx of money, to navigating the crooked world of organized crime that controlled the sport of boxing. We end by talking about how Rocky is both an inspiring and tragic figure.

Show Highlights

- How Mike became captivated by Rocky Marciano

- The importance of boxing to mid-20th century America

- What was Rocky’s childhood like?

- Rocky’s WWII service

- The inauspicious start of Rocky’s boxing career

- The fight that catapulted Rocky to the national stage

- How his fight with Carmine Vingo changed Rocky’s life and career

- Why Rocky walked away from boxing

- The mob connections to boxing in the mid-20th century

- What does Rocky do after his boxing career ended?

- Rocky’s untimely death, and his family’s troubled finances

- Why boxer’s stories tend to be both so inspiring and so tragic

- What sort of lessons did Mike take from writing about Rocky?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Prince of Providence by Mike Stanton

- My interview with Paul Beston about the American heavyweight kings of the 20th century

- James J. Braddock

- Carmine Vingo

- Rocky’s legendary “Suzie Q” punch

- Al Weill (Rocky’s manager)

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Squarespace. Creating a website has never been different. Start your free trial today at Squarespace.com/manliness and enter code “manliness” at checkout to get 10% off your first purchase.

The Great Courses Plus. Better yourself this year by learning new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to The Great Courses Plus. Get a free trial by visiting thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Rocky Marciano was a slow, stocky kid with short arms and stubby legs. He wasn’t the kind of kid you’d pick to one day be an elite boxer. Yet, he went on to become the only undefeated heavyweight champion boxer in history. In the process, Marciano became a cultural icon in 1950s America, rubbing shoulders with presidents, movie stars, and gangsters.

How does someone who got a late start in the sport become one of boxing’s greatest athletes, and what happens to a man when fame and fortune are suddenly thrust upon him? My guest today explores those questions in his new book, Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a Crooked World. His name is Mike Stanton, and today on the show, Mike shares how grit, discipline, and fate led Rocky to become the only undefeated heavyweight fighter in boxing history. Mike then shares the challenges Rocky faced with his newfound fame, from balancing work and family, managing a huge influx of money, to navigating the crooked world of organized crime that controlled the world of boxing. We’re going to be talking about how Rocky is both an inspiring and tragic figure.

After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/marciano. Mike joins me now via clearcast.io.

Mike Stanton, welcome to the show.

Mike Stanton: Hi, Brett. How are you?

Brett McKay: Doing well. Well, you got a new bio out about one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time. Some would say … This is up for debate. We’ll talk about whether he is the greatest, but one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time, that’s Rocky Marciano. I’m curious. Were there a lot of bios about Rocky or were you surprised at how little there was written about him when you first started thinking about this project?

Mike Stanton: There were a couple of good bios, but not a lot and not anything real recently. I thought that Rocky was just such a great story and such an embodiment of so much of American history as well as boxing in the middle of the 20th century that I thought his story deserved to be told to a new generation of people who might know who he is, know that he’s history’s only unbeaten champion, but don’t really know anything beyond the broad outlines.

Brett McKay: I’m curious. What was your draw to it personally? You said in the book you were 11 years old when he died, so that means-

Mike Stanton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: … you were about two years old when he retired, so you probably never saw him fight live, missed the period-

Mike Stanton: No.

Brett McKay: … when he was the biggest thing in America. Without that firsthand experience, what drew you to writing about him?

Mike Stanton: Well, a couple of things. First of all, I always believed that all history is biography, and I love history and I love telling stories about America and who we are and how we got here, and Rocky seemed like a great embodiment of that. I discovered his story as a long-time newspaper reporter in Providence, Rhode Island, and I wrote a book, Prince of Providence, about the long-time mayor, Buddy Cianci, who was a very colorful rogue and the mayor in more recent times.

When he was a boy, I discovered in my research, his father would take him to Fight Night at the Rhode Island Auditorium in Providence. This would have been in the late 1940s, early 1950s, and that was when Rocky Marciano was the headliner there. He came from Brockton, Massachusetts, about 35 miles away. I was just fascinated by that culture. First of all, not just in Providence, but across America and around the world, boxing was one of the biggest sports back in that era. If you were the heavyweight champion of the world, everybody knew who you were. You walked with presidents and kings and movie stars.

I was also interested in that whole colorful guys-and-dolls era of the characters who lurked around boxing, the Mafia, the spectacle, the big fight in a smoked-filled arena in Madison Square Garden, and then Toots Shor’s and the nightclub scene afterwards.

Brett McKay: How big of a deal was he during the 1950s and how much of a cultural impact did he have on America?

Mike Stanton: He was huge. If you want to understand America in the 1940s and ’50s, you need to know about Rocky Marciano. He was the heavyweight champion of the world from 1952 to ’56, and that was that postwar era in America. After World War II, there was this euphoria, and he kind of embodied the American spirit of anything was possible, anyone could be a contender. He was also the poster boy for American might makes right in the Cold War era that we were entered into. In fact, the Speaker of the U.S. Congress actually held him up as a symbol of American superiority, and his manager said that he punched like the atomic bomb. He was really a reflection of that era.

This is kind of a darker side of that era. He was viewed by a lot of Americans as the great white hope, and that wasn’t a mantle he put on himself. He had a good relationship with black fighters. He respected what they went through, and I get into a lot of that in the book, the racial climate, but that was how he was viewed. When he won the championship, he went to the White House and President Eisenhower measured his fist, and Joe DiMaggio was standing there. Everybody wanted to meet Rocky.

Brett McKay: Yeah. He was the first white heavyweight champion of the world for, I think, 15 or 20 years. Right?

Mike Stanton: Yeah, since Joe Louis knocked out James Braddock in 1937 to break the color line that had been enforced in boxing since the early 1900s when the controversial Jack Johnson was the champion. Joe Louis, of course, he transcended race. He was the American champion who beat Max Schmeling, Hitler’s champion in the years leading up to World War II. Then he served in the Army during the war and was an American hero, and he was a hero of Rocky’s. Rocky was listening as a boy on the radio at the Brockton Fairgrounds when Louis knocked out Schmeling. Years later, when Rocky has to face Louis and knocks out his boyhood idol to put him on the path to the title, Rocky cried.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, we can talk about that in a bit. Let’s get to his … What led to him becoming the heavyweight champion of the world? Because I knew nothing about, hardly anything about Rocky before this book. What was he like as a boy? I’ve read a lot of other biographies of fighters, and you could see signs that they would be a boxer, right?

Mike Stanton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Early in life because they get in lots of scraps or they found a local gym, they just hung out there all the time. Was Rocky like that? Was it like you could see from a young age he was destined to become the heavyweight champion of the world?

Mike Stanton: Yes and no. The first thing he loved hitting was a baseball. He loved to play baseball, but he loved sports of all kinds. He was a classic immigrant son. Father came over from Italy, mother came over from Italy. They met in Brockton. The father worked in a shoe factory. Brockton was the shoe factory capital, sent out 12 million pairs a year around the world. They lived on a big playground, and Rocky was outdoors in all weather, playing all sports.

The other thing, boxing was a big part of our culture back then, and so boys fought. Kids would set up rings in the neighborhood in someone’s back yard, and they would have a fight. They would put on the oversize gloves and go at it. Kids fought over bragging rights, different ethnic groups in Brockton. The Irish kids and the Italian kids would fight it out or friends would settle their differences, but then they would blow over like a summer storm.

Rocky was a big, strong, husky kid, great appetite, as I said, loved sports, kind of quiet, but he hung out with some friends who were very mischievous and would get into fights and then they would call on Rocky, the strong, silent one, to kind of restore order. Rocky had a neighborhood reputation as the strongest kid in the neighborhood, and he did a little fooling around boxing, but all kids did that then.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What was his relationship like with his parents?

Mike Stanton: It was very close. He was the eldest son in a family of six, three boys and three girls. The oldest son in a first-generation immigrant family has a special place. He would be the one that would go to the school with his parents, who didn’t speak English very well, if one of the other siblings was having trouble with a teacher, and he was the one, when he got older, who would get a paper route and other odd jobs to try to make money to help the family make ends meet.

They grew up. They were in the Italian second ward of Brockton. It was a working-class neighborhood, and they struggled during the Depression, but his father kept working and they made ends meet. In some ways, it was a very idyllic childhood, and he was very close with his parents, and through all the twists and turns that his life later took, he always remained close to them. He always had that pride in being their breadwinner.

Brett McKay: You mentioned these friends that he hung out with. These friendships he made, they weren’t just childhood friendships. These lasted throughout his entire life. Some of these guys even had a big role in his career as a boxer.

Mike Stanton: Yeah. What’s interesting about Rocky is that boxing is a pretty cutthroat business. It was a very cutthroat sport, and Rocky learned to trust the people who had been with him the longest. The people that came along later, for the most part, he knew he couldn’t trust them, so he always … Brockton was always his touchstone. His oldest friends were always the ones he trusted the most and who were by his side.

One friend, in particular, who was a few years older, Allie Colombo, lived next door, always organized baseball games, and Allie was the one who really pushed him when he started out in boxing and really didn’t know his way and didn’t know how to go about it. Allie was there right through his entire career.

Other friends would come to his training camps at Grossinger’s and keep his spirits up. There was that bond he had. The other thing, this was a gambling culture. Everybody bet on things, and when Rocky went into the ring, he said, “I knew I could never fall down. For the people of Brockton, I would always get up because I knew they were counting on me. They were betting their money on me, and I wasn’t going to let the down.”

Brett McKay: Yeah. So, not much interest in … He did have an interest in boxing, but he was more of a baseball player as a young boy. I love reading biographies about famous people or people who did great things from decades gone by. I think a lot of young people today think this idea or this feeling of listlessness or not knowing what they’re supposed to do with their lives is something new. Their grandfathers had it all figured out when they were 22 as well, but when you read these biographies of these guys, they were just as clueless as a 20-something is today. Seemed like Rocky was the same way. He was in his early 20s, and he didn’t really have his bearings. He didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life.

Mike Stanton: No. Well, you know what? Back then, his ticket … There was a one-way ticket to the shoe factory, and for a blue collar Italian kid without a lot of other opportunities, without an education … He dropped out of high school. He was the first to admit that he wasn’t a big lover of books. Sports was his way out, and initially, he thought that would be baseball. He could hit the ball a mile. He was short, stout, prototypical catcher, but maybe …

Life has its twists, and maybe it all happened for a reason, but he went down to spring training with the Chicago Cubs in 1947, and he had a tryout with them. He hit the ball pretty well, but the supreme irony is that he couldn’t make a strong throw to second base from catcher. Here he is, the greatest slugger in heavyweight history, he can’t make a strong throw to second, and that was his undoing in baseball.

Brett McKay: What do you think held him back from having that strong throw, despite being able to throw a really strong punch?

Mike Stanton: Well, he said that he had injured his arm in the Army playing sports. It was never quite clear. But let’s face it, the competition is stiff to make the major league baseball rosters, especially back then when there were far fewer teams. There were a lot of good ballplayers from Brockton. He went down with some friends who were good ballplayers, and some stuck in the minors for a few years, and one made it to the Triple-A Dodger’s team but then got hurt and stopped playing.

Actually, they were signed by the scout that signed the Chicago Cubs player who was the inspiration for the movie The Natural. A lot of good ballplayers then, and that was Rocky’s love. Later, when he became a successful boxer, he found himself being friends with Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio and other great baseball stars like Yogi Berra.

Brett McKay: Yeah. But still, at this point, he wasn’t boxing regularly.

Mike Stanton: Well, no. What’s interesting, though, when you … Like I was saying, everything happens for a reason. When he became a boxer, his trainer incorporated some of his baseball mannerisms, particularly his catcher’s crouch, into his fighting style, because Rocky was short and he needed to get up close to his opponents to be able to hit them and that opened him up to being hit, so he had to be down low so they couldn’t get at him.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, another thing that added to Marciano’s all-American appeal when he became a celebrity was that he served in the Army during World War II, but the thing is he never really talked about it much. Why is that?

Mike Stanton: Well, one of the things I discovered in my research for this book … I had heard some rumblings he had some problems in the Army. When I got his Army file from the National Archives in St. Louis, I discovered that he had been court-martialed along with another G.I. for robbing and assaulting two British civilians. Rocky was over in England on the eve of the D-Day invasion. He was in an Army combat engineers unit that was going to deploy to Normandy as part of the invasion.

On the night he got into trouble, he was supposed to be confined to base because the D-Day was coming and he and this friend snuck off base. They went to a pub. They met a couple of British civilians who worked for an airplane company. They were back at the civilians’ apartment, and they got into a fight and they robbed them and punched them and were later court-martialed, so they never deployed to Normandy.

Rocky wound up being sentenced and wound up serving two years in a military prison back in Indiana. This was in the spring of 1944, around the time of D-Day, and then he was freed in the spring of 1946, the year after the war ended. Unlike most people who were drafted into the Army for World War II, whose service ended with the war, Rocky stayed in through the end of 1946 so he could come out with an honorable discharge.

That was really a pivotal point when his boxing career really begins in a more formal way, because he goes out and serves in Fort Lewis, Washington state, and he boxes on the Army boxing team, which is a very good team. He starts to fight regularly for the first time, and he gets himself into shape. He had fought an amateur fight back in Brockton before he went out to Fort Lewis, but he was totally out of shape. He went over to his uncle’s house and he had a big dish of macaroni before the fight, and he ran out of gas in the second round and he kneed his opponent in the groin and was disqualified.

After that, he said, “I’m not going to embarrass myself anymore.” He got himself into shape in the Army, and he boxed pretty well out there. He went to the National AAU Championships in Portland, Oregon, where he reached the finals, and another fateful turn happened in his career at this point. In the semis, because he was so clumsy … He could hit hard but he was very clumsy. He hit his opponent on the head, and he fractured his knuckle very severely, and it could have been a career-ending injury.

Fatefully, there was a Japanese American Army surgeon at Fort Lewis, Thomas Takeda, who performed an experimental operation and saved Rocky’s knuckle, and it allowed him to be able to fight. Interestingly, Dr. Takeda’s family had been interned in the Japanese American prison camps during World War II, but Dr. Takeda was in medical school and was spared that, and he was in the right place at the right time as far as Rocky’s career was concerned.

Brett McKay: When he started boxing on the Army team, did he have any formal boxing training or did he just kind of get in there and sort of going back, falling back into those schoolyard scraps he had, that’s how he boxed?

Mike Stanton: Yeah, that’s how he boxed. They had coaches on the Army team and they started to give him advice. He was training so he could have the energy to go the distance in the fights he had, unless he knocked his opponent out, as he often did. But he was very rude and crude, and well into his career as a professional he was as well, but this was the beginning of the formal education of Rocky Marciano in the ring.

Brett McKay: How old was he at this point? Let’s kind of get some context there?

Mike Stanton: He would have been about 22, 23 years old at this point.

Brett McKay: 22 years old, so it’s kind of a late start-

Mike Stanton: Yes.

Brett McKay: … to get into the boxing game.

Mike Stanton: Yeah. His trainer, Charley Goldman, once said, “He started way too late. I got a guy who’s got two left feet. He’s stoop-shouldered, he’s balding. He don’t look so good with the moves in the ring, but his opponents don’t look so good on the canvas either.”

Brett McKay: Right. At what point did Rocky think like, “Boxing is going to be my ticket out of the shoe factory”? When did he think that that was going to be reality?

Mike Stanton: Well, after he got out of the Army at the beginning of 1947, he carried on his boxing experience. He fought some amateur fights and Gold Gloves fights in New England, but then he had his baseball tryout with the Cubs that spring, and he really wasn’t so enamored with boxing. It was just a way to make a paycheck while he waited for the baseball career to take off. Once that didn’t take off, he came back in the spring of ’47, and that was when he started boxing in earnest.

His friend Allie Colombo was the first one to really see that he thought Rocky could go all the way, which seems pretty ridiculous to think about back then, but that was the dream that Allie had, and Rocky didn’t really have any alternatives. The interesting thing … You asked about his relationship with his parents. The first son of an Italian mother, she hated the idea of him fighting, didn’t want to see him fight, would be upset about it, so he used to sneak out of the house to train.

In the spring of ’47, he snuck out to Holyoke, Massachusetts, and he fought his first professional fight. He fought it under an assumed name, Rocky Mac, an Irish name on St. Patrick’s Day in an Irish working-class city, and he won his first fight. Then he kind of crept back to Brockton without letting his mother know. Later, when she did find out he was fighting, she always made him promise that he would stop if he ever got hurt, and she’d always make him lift up his shirt and inspect his body for marks to see if he could keep fighting.

Brett McKay: That affected his fighting style because he would stand in certain ways he wouldn’t do today.

Mike Stanton: It did. When he later got a seasoned manager and trainer and they looked at him and said, “Why are you holding your hands up like that and letting people hit you in the stomach?” He goes, “Well, I just figure I’d let them punch themselves out. I don’t want to get hit in the face because that would leave a mark, and then my mom would see it.”

His mother was this indomitable woman, Pasqualina, or Lina, and that’s where he got his strength from. She was a big, powerful woman, very gregarious, vivacious, the heart and soul of that family. His friends would say that she was the one person that people feared in his house.

Brett McKay: Rocky starts boxing semiprofessionally. He’s trying to maintain an amateur status so he can be eligible for the AAU Golden Gloves.

Mike Stanton: Right.

Brett McKay: But those rules got flouted all the time. People would fight like he did, fight under different names.

Mike Stanton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: When did he get connected with a legit manager and trainer that would lead him and train him to actually turn pro?

Mike Stanton: Well, that would be in the summer of 1948. He’d been boxing some amateur fights. He’d won the New England Golden Gloves in Lowell, Massachusetts. He went down to New York where he lost to Coley Wallace, who was kind of a young, upcoming black fighter who was hailed as the next Joe Louis. The only way he was the next Joe Louis was he played him in a movie. But Wallace won a controversial decision in New York that a lot of people felt should have gone to Rocky, and that probably cost Rocky a shot at the Olympics, the Olympic team.

At that point, the local manager in Brockton that Rocky had for amateur fights, they weren’t really getting along and Rocky had some family advisors who’d been in the fight game, and they said, “You’ve got to go to New York. You’ve got to get a connect manager, and New York is the center of the boxing universe. Boxing is such a treacherous sport, you got to have a guy with connections who’s going to look out for you, get you the proper training and get you the fights to put you on the path to the top.”

So, he went to New York, and he got a meeting with the premier manager at the time, a guy named Al Weill, who was a great character. Weill was the matchmaker for the International Boxing Club, which controlled boxing, or he would be, and he was very influential. He’d had three champions in other weight classes. So, he got hooked up with Al Weill, and Al Weill brought along his trainer, Charley Goldman, who was a walking encyclopedia of boxing knowledge, earned in 400 bantamweight fights of his own in the early 1900s. With those two guys in his corner, Rocky started a more formal education in the ring that would later put him on the path to the title.

Brett McKay: Initially, these guys didn’t think much of Rocky.

Mike Stanton: No, they didn’t. He was a guy who was very clumsy, he was very awkward, he was slow, he was short. He was old for a fighter starting out. They actually brought him down to the gym down in lower Manhattan, a CYO gym, and just had him spar a few rounds with a guy. They’re looking at each other, Goldman and Weill, and some of the other guys in the gym, and they’re shaking their heads. Then suddenly, out of nowhere, Rocky floors the guy with this thunderous looping right, and then they started to take notice.

Later, Charley Goldman would nickname that punch the Susie Q. It was that punch that convinced them and also Rocky’s dedication. They could tell that he really wanted it. He wasn’t going to run around and fool around with girls and party. He was going to train, and he was a monk about it, and so they took a chance on him. It didn’t cost them anything. They just told him to train. They weren’t putting any money into him at the beginning, and because Rocky didn’t really have a lot of money, he was digging ditches back in Brockton, they wanted him to move to New York and train, but they didn’t want to pay his expenses.

He said, “Well, I can’t afford that,” so Weill, who’s connected all over the place, sent him to Providence, Rhode Island, which was the fight capital of New England back then as well as the mob capital, and that’s where Rocky started to fight because he could live at home in Brockton and he could go over to Providence for fights. Then he would hitch a ride on overnight produce trucks down from Brockton to New York to train with Goldman, and he lived at the YMCA for a dollar a night.

Brett McKay: Right. Yeah, this is the prototypical boxing story. He was living it fully.

Mike Stanton: Yeah. I love the images I found of him and his friend Allie, who was by his side for all of this. They would roll off the produce truck at 4:00 in the morning in lower Manhattan, and the sun would be coming up and they didn’t have much money in their pockets. They would just walk the street, and at night for entertainment, they would walk up and down Broadway, watching the people in their fine clothes and dream about life.

One time, he saw the great fighter Willie Pep, who was a champion, and he saw him walking up Broadway with a beautiful woman on his arm. They were both well-dressed, and he bought her a flower and pinned it to her lapel and they went into a fancy theater. Rocky dreamed of having that life.

Brett McKay: In Providence he’s doing some fights, doing the work. What was the fight that brought Rocky to the national stage, yeah, he was a contender?

Mike Stanton: Yeah. Well, he built his record up in Providence, and he became a real crowd favorite there. First of all, Providence is a big Italian American town, and so they loved him. Everybody loved his knockout punch. It became a tradition in Providence that whenever Rocky would be ready to knock out one of his opponents, he would hit him with his punch, his Susie Q, and the guy would kind of stand there and topple for a minute, and then he would crash to the canvas and the crowd would yell, “Timber.”

So, Rocky started to develop a reputation, and after a few fights, the local promoter was initially angry with Al Weill because Al Weill would always betray these other managers and cut deals that would screw them. They kept trying to put guys in the ring that would beat Rocky and shut Weill up, but Rocky kept knocking them out. Finally, the local promoter said, “Al, you better lock this guy up. He’s starting to get a following.” So, Weill signed him to a contract, and that’s when he started to come down to New York and train.

He kept winning all these fights, and then he finally gets to the point where he has his first big feature fight in Madison Square Garden a few nights before New Year’s Eve in 1949. He fights a guy named Carmine Vingo, who is also an unbeaten, up-and-coming but younger Italian fighter from the Bronx who has a big following there. His name is Bingo Vingo, and they have one of these great unknown fights that really puts Rocky on the map.

In some ways, it puts him on the map for the wrong reasons because they start wailing away on each other, and it’s like two heavyweights fighting at the speed and intensity of lightweights and they’re landing thunderous punches on each other. The New York Times writer wrote that it would seem like more than human endurance could stand. Finally, in the third or fourth round, Vingo hit Rocky a tremendous shot to the chest, and Rocky later said he blacked out, but he stayed on his feet and just went into a clinch until he could regain his senses.

In the sixth round, with Vingo tiring, Rocky hit him with a thunderous right, put him on the canvas. Then his head kind of thumped up and hit the canvas again, and while Rocky was celebrating, Vingo slipped into a coma. Later, the ring doctor tried to revive him, was unsuccessful. They called an ambulance. They couldn’t get an ambulance to come, so they piled the blankets and coats on him and carried him through the streets of Manhattan to a nearby hospital.

Then Rocky heard about it and went over there and stood vigil as Vingo’s family and fiancé came, and he basically fought to see if he would live or die. A few days later, he pulls out of the coma, and he eventually recovers but never will fight again. He’s blinded in one eye. He has a permanent limp, and for the rest of his life, Vingo never remembered that fight. The last thing he remembered was the six steps leading up from the floor of Madison Square Garden to the ring, and then the next thing he remembers was lying in the hospital bed and seeing his mother.

Brett McKay: How did that affect the rest of Rocky’s career? Because I’m sure knowing that you almost killed a guy would make you a bit timid next time you go into the ring.

Mike Stanton: Absolutely. And it did, but the longer term effect would have been had Vingo died. Rocky said that he’s not sure he could have continued had Vingo died. I’m not sure that’s true, and Rocky’s friends think he would have continued, but still, you wonder how the effect it’s going to have on you, and that’s the specter of boxing, isn’t it? Death in the ring that lurks. And it’s interesting, in researching this period, I found that as popular as boxing was, it was kind of like the NFL of its day. People loved it, but they also had this love/hate relationship with it, and they realized that they were lusting for blood and lusting for the thrill of seeing another man potentially killed or maimed.

There was a lot of hand-wringing publicly about whether boxing had a role in society. Interestingly, Rocky later came around to some of those views later in life, but at the time, there was a lot of talk about what kind of reforms can we put into boxing to make it safer? Can you make it safer? It did bother Rocky. He was very on edge about what had happened. And other great fighters, his trainer had seen other great fighters lose their killer instinct.

His next fight was his next big fight in the Garden against Roland La Starza, who was another unbeaten, young, darling heavyweight of the New York press. He was very stylistic. He had gone to local college, but he was a guy that lacked the killer instinct. They kind of compared it to a Dempsey versus Tunney fight, Dempsey being Rocky, the hard hitter, and Tunney being the more thoughtful, strategic, defensive fighter. Rocky won that fight in a very narrow controversial 10-round decision in Madison Square Garden. That really put him on a path to being a contender, and from then on, his fights were headliner fights. He wasn’t on the undercard after that fight in 1950 against La Starza.

Brett McKay: Right. Then he eventually fights Joe Louis. This wasn’t for the title, though, correct? There was another guy who held the title. Joe Louis-

Mike Stanton: Jersey Joe Walcott and Ezzard Charles were champions, in reverse order, after Louis stepped down. Then what happened was, the tragedy of Joe Louis’ life was he had a lot of debts and he needed to come back into the ring to try to make money, even though he was past his prime, but he was still the Brown Bomber. He was still Joe Louis. When Rocky was rising to contender status, Louis was suddenly the match that was made for them to face each other.

When Rocky won that fight in October of 1951, he was kind of declared the champion-in-waiting. Again, some of this goes to racial overtones of the era, that after Joe Louis, the black champions were kind of unsung and really never really connected with the public, and Rocky was seen as the fresh face, the white face, the great white hope, if you will. Once he beat Joe Louis, his idol, he was the top contender to the crown.

Brett McKay: I wonder if Rocky seeing Joe Louis had an influence on how Rocky decided to end his career, because Joe Louis’ story is super sad. That was a story of a lot of heavyweight, a lot of boxers in that time. They would go and they’d make a lot of money, and they retire and they would need more money, so they’d come out of retirement and they’re past their prime and they’re still trying to win one more fight, and it’s sad. Right?

Mike Stanton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: It’s just really tragic. I wonder if Rocky saw that as like, “I’m not going to do that,” so that’s why he just decided, “I’m going to walk away. I’m going to walk away completely from boxing.”

Mike Stanton: Yeah. He was 49 and 0. He was in his early 30s. He still had some fights left in him. 50 and 0 would have been a nice round number, but there were two things that Rocky was afraid of. He was afraid of not having money. He grew up in the Depression. He also saw a lot of fighters who got fleeced and left with nothing. They lived the good life while it was there, and then it was gone. He also saw a lot of broken-down fighters who are sitting alone, mumbling in bars and their wits aren’t all about them, and he feared that.

Those are the two things he feared. He was a real assassin in the ring, but he was a pretty gentle man out of it and he didn’t really hold grudges against fighters. The one time he really got mad at a fighter, though, was when he was champion and he fought Roland La Starza in a rematch, and he was angry that before the fight, La Starza was quoted making some comments about the way Rocky fights, he takes so many punches, he’s going to become punch-drunk. That really struck a nerve with Rocky because he feared that, and he didn’t want that. He knew when to walk away.

There were some other reasons we can get into about his manager stealing from him. That again goes back to his fear of not having enough money, but he had the presence of mind, and later in life, he helped Joe Louis. He helped Joe Louis get jobs. When he met Muhammad Ali late in his life, Ali’s wife pulled Rocky aside one day and said, “Do you think I can get Muhammad to retire?” Rocky looked at her and said, “No, darling. He’s got the lust in his eye and he’s just going to have to … He’s too big an ego. He’s not being to stop.”

Brett McKay: Yeah. You mentioned once Rocky decided he was going to do boxing, he became pretty much a monk. He quit smoking, he quit drinking. Then you go into his training camps and he becomes even more monk-like. Walk us through his training regimen to get ready for a fight, the extremes he’d go to to make sure he was in tip-top shape for a fight.

Mike Stanton: Rocky realized that his body was his temple, and he would train for months. He would run relentlessly, and he would box several hundred rounds to prepare for a 10- or 15-round fight. The other thing about him is even when he wasn’t formally in training, he would always be working out. His brother talked about waking up in the middle of the night and there’s Rocky on the floor doing push-ups with a chair or some exercise, squeezing a ball with his hand to strengthen the knuckles that he had broken.

So, he was always training, and he liked the heat. He said, “Oh, this reminds me of digging ditches in Brockton.” He liked enduring the punishment. Sometimes he would go up to Grossinger’s in the Catskill Mountains of New York in the winter, and he said that the cold wind would toughen his skin. He was a rough, tough guy.

Brett McKay: Yeah, yeah. Not only was it the physical training was hard. He would sort of, I don’t know, spiritually, psychologically prepare himself for this fight. He would have no distractions whatsoever. He wouldn’t see his family. He would cut off mail. He was just thinking about fighting all the time.

Mike Stanton: Yeah, he wouldn’t read stories about his opponents, and he would just paint mental pictures. In some ways, he was a good model for athletes today about how to train. He was ahead of his time in terms of avoiding fried foods and eating green vegetables and things like that. He also somewhere early on, somebody told him don’t lift weights and get yourself all bulked up. He was more about flexibility. Even though he was not the most graceful of fighters, he kind of incorporated that into his training.

One of the things he did when he was young, he would go to the Brockton YMCA and get in the swimming pool, and he would throw punches underwater, and he would go mock three rounds. People would come into the pool area and see the water sloshing up over the sides from the force of his underwater punching.

Brett McKay: Right. He had a lot of discipline. He knew how to just discipline himself.

Mike Stanton: Incredible discipline. There’s a great story I found. There was a Hollywood bombshell actress named Jane Mansfield, kind of like a Marilyn Monroe type, and she’s at Grossinger’s. His training camp was also a big entertainment mecca, a lot of Hollywood stars would go and entertain the people at the resort down the hill from where Rocky trained, so there were always stars around.

Jane Mansfield was at Grossinger’s once when Rocky was training, and some friends thought it would be kind of a funny joke to send her into his cabin to see if she could seduce him. She went in, and not many men would say no to Jane Mansfield back then, but he said, “No.” And she left his cabin in a huff, frustrated that he had rejected her, which she wasn’t accustomed to.

Brett McKay: Right.

Mike Stanton: But that was Rocky. He said there would be plenty of time for living the good life later, but, again, it was, I think, that fear that drove him and that pride. Even if he got knocked down while he was sparring, he would want to spar more or say, “I just slipped and fell.” There was that fierce pride.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah. You mentioned earlier that when he fought, he felt the weight of the world on his shoulders. He wasn’t just fighting for him and his family. We can talk about his family life here in a bit, but he’s also fighting for the people in Brockton, because he knew people were probably betting enormous amounts of money on him, and he couldn’t let them down.

Mike Stanton: Yeah, they were. It was part of the culture then. People gambled. As a kid, he would go to these illegal dice games in the woods behind the ball field where there was a one-legged gambler from Providence named Peg Leg Pete would run them. So, gambling was ingrained in the culture. It was interesting. I found that when Rocky started his rise in boxing, started getting the bigger fights, the people in Brockton, little old Italian ladies and men would take the money, the dollar bills stashed in their coffee tins and they would bet it on Rocky. Then he’d win and they’d take the winnings and they’d roll it over and bet on the next fight and the next fight.

Then you hear stories about people in Brockton would be buying refrigerators and stoves and cars and even new houses. There was one taxi driver after Rocky became champion, he told a visitor that before every fight, he takes this elderly Italian couple to the local loan company so they can borrow money. He said, “Heaven help Brockton if Rocky ever loses,” but he never did, and he said, “You know, I knew that these people were counting on me and for them, I would always get up.”

Brett McKay: Yeah. Rocky’s Italian American, family obviously very important. He gets married. Took him a while because his manager didn’t want him to get married because it would distract from boxing, but he finally does get married to his wife, Barbara. Right? Is that her name?

Mike Stanton: Yeah. He gets married to Barbara Cousins.

Brett McKay: Yeah. He was gone all the time, so how did his boxing career … How did he balance boxing or family, or did he?

Mike Stanton: Well, that was a real tension. Not so much in his marriage at the time. It was more a tension within himself because his wife, Barbara, she was a good natural athlete and she accepted what he was doing and she was willing to make the sacrifice, but it was hard on Rocky. He’d talk about, “I just got married,” or, “I’m engaged, and I can’t see my wife or my fiancé.”

Then when they had a daughter after he became champion, he would bemoan, “You know, I miss my family. I haven’t seen my daughter in eight months. I go home and she doesn’t even know me. She’s scared of me and runs away.” This is a guy that grew up with strong family bonds, so that was hard. But he also loved boxing. He loved training, and he was willing to make the sacrifice, and he didn’t regret doing it.

Brett McKay: What I found interesting about Rocky’s career is even though he was winning every match he was in and knocking people out, the journalists and the boxing critics weren’t … They still, they weren’t that … They were always criticizing him and saying he wasn’t actually that great of a boxer. What was the critique against Rocky, despite him winning every single match he was put in?

Mike Stanton: Well, he was slow. He was awkward. He was clumsy. He wasn’t a great stylist. People were used to the stylists like Joe Louis, who were very graceful and good counterpunchers and good strategists or quick and could move in and out, and he was like a bulldozer. He was like a working-class guy. He’d come in with his pickax and he’d just keep banging on the brick wall, seemingly futility until suddenly the wall crumbled.

Finally, again, the Cold War America started to embrace that heavy puncher, and they started to like that about him. He was a guy who could never win on dial points. Even as he advanced in his career, he and his trainer would admit that he’s not the most graceful guy, but there’s more than one way to win a fight and Rocky had the punch, and he also had the ability to take a punch and take incredible punishment and keep going when he was knocked down, when he was bloody, when his nose was hanging in tatters and bleeding like a faucet. He just kept coming.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The dedication or determination, the grit that he had, that surprised opponents. They’d be like, “I gave him a really good wallop, but he just, he didn’t go down. He just kept coming at me.”

Mike Stanton: Yeah. One opponent said it was like hitting the side of a rhino. Archie Moore said it was like wading into a moving airplane propeller. Another opponent early on said that every time Rocky hit you, you saw a flash of light.

Brett McKay: Right. Let’s talk about his manager, because his manager, you said he’s a character. Someone, I think, described him as Hitler, Mussolini rolled into one or something like that, had connections to the mob. What was Rocky’s … Obviously, he’s Italian American. He’s a boxer. He must have rubbed shoulder. Since an early day, since he was a kid, he was also going … He’s gambling. He probably saw it, encountered it. What did he think about it? Was it one of those things where he was both … There was a tension there? He was both appalled and sort of drawn to it at the same time?

Mike Stanton: Very much a tension. That would manifest itself more after he retired from the ring and he needed a new outlet for the adrenalin rush of boxing, and he would hang around these dangerous mobsters who all adored him. They adored him because he was one of them. He was a countryman, but also because he did them proud, and he resented that anti-Italian prejudice and stereotype that mobsters brought onto his race. He resented the corruption in boxing, and the mob control permeated it. It didn’t matter whether you were black, Italian, Latino, Irish. If you were a boxer and you were in the mix, you had to deal with the mob in some way, shape, or form because they were in the background behind all of it.

Of course, the flip side of the coin, Rocky gets one of the most politically-connected managers in boxing, Al Weill, and that means that Al Weill is also answers to Frankie Carbo, who is a notorious mobster known as the underworld’s commissioner of boxing as well as a hit man for Murder, Inc., implicated in five murders, including his former partner, Bugsy Siegel.

Al Weill, though, was a real character and there was real tension between Rocky and Weill throughout his career. First of all, he hitches his star to this big-time manager, and he’s happy about that because he’s going to get him a shot at the title. Al Weill was in interesting character. He and Charley Goldman came of age, both poor immigrants, Jewish immigrants from Europe in the early 1900s. They come to New York. They battle their way up. Weill, interestingly, he started dancing in the dance halls and winning $5.00 in these dance competitions, and that’s how he survived.

One of his rivals was a young, up-and-coming future star actor named George Raft. This is in Manhattan. Later, he gravitates into the boxing game, and it turns out he’s got a real gift for matching fighters, and so he gets into that, but he’s still hustling odd jobs. Boxing is still illegal a lot of the years in the early 1900s. He’s working at the Golden City Amusement Park on the waterfront in Brooklyn in Canarsie, and he’s running the high striker, getting guys to impress their girls by taking the mallet and hitting the bell and winning a prize.

Nearby, he meets this guy, this old broken-down boxer named Charley Goldman, who’s running the wheel of fortune. They wind up striking up this great partnership that produces three world champions, a lightweight Lou Ambers, a featherweight Joey Archibald, and a welterweight in Marty Servo. The one crown that’s eluded them is the heavyweight crown, the most glamorous of all. When they take Rocky on, Rocky’s eager because now he’s got the best management, but Weill is very domineering. There’s one profile that compares him to Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and Simon Legree rolled into one, and this is a favorable profile.

Weill was the master manipulator. He was a control freak, and he would tell his fighters when to eat, when to sleep, where to go, whether they could date, when they could marry. He was very domineering. He was very crude and abrasive and didn’t always treat Rocky well, and Rocky bristled at that, but he had enough restraint that he knew he had to put up with that to get to the title. That was the uneasy marriage that lasted throughout his career and eventually broke up and was a big reason that Rocky retired when he did.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah, let’s talk about his retirement. You mentioned that he loved boxing, he loved training, but when he was getting to win 48, 47, he started talking to people, was like, “It just doesn’t do it for me anymore. I climbed all the mountains. What else am I supposed to do?” There was that. What else about his relationship with Weill that made him want to retire as well?

Mike Stanton: Well, as I said, Weill was connected to the mob, and the mob would skim the money from a lot of these fights because it became a very … We always know. Damon Runyon, Guys and Dolls, that’s Rocky’s life, and that’s the world of boxing. So, we know the mob has always been around the fight game and all these characters, but what people don’t realize, I discovered in researching this book, was that after World War II, boxing becomes bigger time because of all the new TV money. TV is suddenly in every American’s home, and the two biggest early forms of entertainment were boxing and I Love Lucy, and so there’s a lot of money now to be made.

So, Weill is taking half of Rocky’s earnings, even for public appearances outside of the ring, which is a lucrative side business for champions. On top of that, Rocky’s starting to hear rumblings that Weill is selling tickets under the table, that he’s not sharing any of the proceeds with Rocky to his big fights, that he’s skimming money off the top of his purses before he divvies it up. Then he’s fighting in San Francisco against Don Cockell in the spring of 1955, his second-to-last fight, and there’s a boxing investigation of the corruption out there that later uncovers a $10,000 check that was cashed and went to Weill that was skimmed off the top of Rocky’s purses.

This was all starting to build up in Rocky, and now he’s the champion, he’s got some independence and he’s just had it, and he’s also burned out from … When you train as hard and as long as he did, even though his career was relatively short, he had had it and he was starting to have some back trouble. He did see what happened to Joe Louis and he did see what happened to some of these other broken-down fighters, and he didn’t want to follow in their path. He decided after he fought Archie Moore in Yankee Stadium in the fall of 1955 that that was it. He was done, and he walked away.

Brett McKay: So, he retires. This guy for the past, was it 10 years, just constantly moving, constantly training, always going after something, what does a guy like that do when there’s nothing to go after, no set goal to go after?

Mike Stanton: Yeah, he kind of drifts. At first, he enjoys it. He’s the most famous man in the world. He can command all kinds of money from business deals, speaking fees. People want to throw money at him. They want to give him land. They want to give him suits, restaurants, hotels, plane flights, and so he’s living the good life and he’s enjoying all the things he deprived himself of when he trained. He’s gorging himself on rich food and beer, and he’s gaining a lot of weight. He’s also starting to become a pretty notorious womanizer, and he also starts hanging out with mob guys. Again, they love him and he’s kind of drawn to the danger and the excitement and the action. So, this becomes his life.

Meanwhile, the country is changing. He retires in 1956. Boxing, this is kind of the last golden age of boxing and it starts to decline in popularity. People wish he would come back. Muhammad Ali comes along to kind of breathe new life into it for his career, and the 1960s comes along and the country is changing. In the late ’50s, he goes down to Cuba and there’s some talk about him getting involved in a mob-run casino down there. Then shortly after, he leaves. He’s supposed to come back. Some of Fidel Castro’s gorillas shoot up the casino, and then Fidel Castro overthrows the government down there and the casinos all have to shut down. So, that deal goes away.

He meets with the notorious mobster Johnny Roselli about taking a stake in a Las Vegas casino, and that deal falls through, but he has a lot of other things going on and he actually does get involved with a Cleveland loan shark named Peter DiGravio and winds up putting some money into DiGravio’s business, and then the IRS is sniffing around. One of the really eccentric things about Rocky in retirement … this goes back to his Depression childhood, I suppose … is he loves cash, doesn’t trust banks. He hides cash in all sorts of bizarre places, toilet bowls, curtain rods. He’s got a friend who has an estate in Florida. He hides it in his bomb shelter.

So, this is Rocky’s life, and he’s traveling around and the IRS is asking this Cleveland loan shark, “Well, where’s all this cash coming from?” And he said, “It’s from Rocky Marciano.” The IRS wants to talk to the loan shark about it, and they want Rocky to answer some questions and Rocky’s heading out to Cleveland when the loan shark is out golfing and he gets shot dead on the course because he’d been having a feud with some local mob bosses about his loan sharking business.

Brett McKay: Yeah. His financial stuff was really interesting. He loved cash, and I think one of his friends rummaged through one of his pants pockets and he found these crumpled up checks for $50,000, $100,000 not cashed. He’s like, “Rocky, why don’t you cash them? It’s $100,000.” He was like, “I don’t like checks. I only like cash.”

Mike Stanton: Yeah. There was one time his nephew told me a story that Rocky goes to a dinner to give a speech, and he walks into the ballroom and he sees a heavy bag hanging from the ceiling. He says, “What’s that for?” And the guy says, “Well, we thought you could hit the bag a few times for the crowd.” Rocky basically looks at the guy and cusses him out and says, “What do you think I am, a trained monkey?” And he goes, “I’ll tell you what. If you want me to hit the bag, you take up a collection and a hundred bucks a pop.” And they look at him like, “Well, where are we going to get the money?” He looks out at this well-dressed crowd and he says, “From them.” Apparently, they raised it and he hit the bag.

There was a sadness about his existence.

Brett McKay: Like a well-trained monkey.

Mike Stanton: It’s the 1960s, the world is changing.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Mike Stanton: I kind of picture that mythical character Don Draper in the TV series Mad Men. He’s kind of wandering through this changing country wondering what his place is, and he’s kind of unmoored from his family. He doesn’t go back to Brockton much. His mother laments that he doesn’t see his family often enough. He still cares about them and he feels almost like a hamster on a wheel, that he has to keep doing this thing so he can bring in money to support the family and fly them to Florida and fly them on vacations.

He takes his nieces down with his daughter to see Chubby Checker and Little Eva and to live this lifestyle. He’s kind of wistful. He looks at his married brothers and sisters and he says, “You know, you have it good. You have a normal life and everybody doesn’t call your name when you walk down the street. You know where you’re going to be sleeping tonight.”

Brett McKay: Also, he dies tragically in a plane crash. The way he kept his finances, hiding cash all over the place, that actually ended up putting his family in financial straits because they didn’t know where the money was at.

Mike Stanton: Yeah, it was terrible. It was this kind of cheapness that did him in, because often, he would get these airline tickets to go fly somewhere to do an appearance, and he would cash in the ticket and he’d find some rich businessman with his own private plane to fly him for free because everybody adored the ex-champ. So, he’s in Chicago and he’s supposed to fly home to Florida where he’s living at that time to celebrate his birthday the next day. This is in 1969 at the end of August.

He gets a last-minute proposition from a mobster pal in Chicago, “Fly out to Des Moines. My nephew has a steakhouse there. Put in an appearance and then you go back home tomorrow.” So, he agrees, and he gets on a little Cessna airplane at Midway Airport in Chicago with the mobster’s nephew and this inexperienced pilot. They fly out toward Des Moines and they fly into a massive Midwest thunderstorm, and the pilot loses visibility and he crashes in a cornfield outside of Des Moines.

Jim Murray from the Los Angeles Times the next day wrote, “Stop the count. He’ll get up. We’re all wishing today that there was an honest referee in a cornfield in Iowa.” But he dies, and now his family doesn’t know where his money is. His daughter later talked about how they hired detectives and they searched for it. They went to some of his friends where they believed he had stashed cash, and suddenly the friends didn’t know nothing, and so they struggled.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I love reading biographies of boxers because their stories are both inspiring, the discipline that Rocky showed during his career, his dedication and determination, his grit, but they’re also tragic. I don’t know why that combination of inspiring and tragic is appealing to me. It makes for a good story, right? I’m curious.

Mike Stanton: It definitely makes for a good story.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’m curious. As you researched and wrote about Rocky Marciano, what life lessons did you take from him, both positive ones, I want to be like that, and also sort of as a warning, don’t emulate that.

Mike Stanton: Well, Rocky was true to himself until he wasn’t, and those are both positive and negative life lessons. Be true to yourself and don’t lose who you are. For most of his remarkable career, he never lost sight of who he was and he never lost sight of his goal, and he put all distractions and obstacles aside in his pursuit of perfection. But he lived, as my subtitle of the book says, in a crooked world, and that tension was what really drew me to this story and really transcends boxing.

It’s surviving in a world that’s changing, where there’s all kinds of hidden intrigue and corruption, and you have to make sacrifices to get where you want to go and try to preserve your humanity in the process. The fact that Rocky kind of walked this tightrope was what really drew me to his story. In some ways, he came out triumphant, and in other ways, of course, his life had a tragic ending.

Brett McKay: Well, Mike, is there someplace people can go to learn more about the book?

Mike Stanton: Well, it’s available online, and at stores everywhere. It’s called Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a Crooked World, and the publisher is Henry Holt.

Brett McKay: Mike Stanton, thanks so much for coming on. This has been a great conversation.

Mike Stanton: Well, thank you, Brett. I appreciate it.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Mike Stanton. He’s the author of the book Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a Crooked World. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. To find out more notes and delve deeper into this topic, go to our show notes at aom.is/marciano.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com, and if you enjoy the show, as an additive, I’d appreciate it if you leave us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who might get something out of it.

As always, thank you for your support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.