Romanticism, not in terms of courtship and bouquets of roses, but as a philosophical approach to life which blossomed in the 19th century, embodies many tenets, including a nostalgia for the past, a heroic view of the world, a firm sense of right and wrong, and the idea that an individual can shape his own destiny, as well as have an outsized impact on the world.

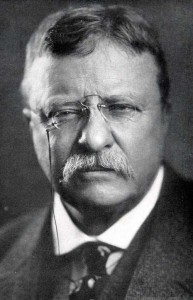

It is through this lens of Romanticism, my guest says, that we can best understand one of the most memorable, influential, and legendary figures in American history: Theodore Roosevelt. His name is H. W. Brands, and he’s a professor of history and the author of numerous books and biographies, including T.R.: The Last Romantic. Today on the show, Bill explains how Teddy Roosevelt was one of the last bearers of the Romantic spirit, where his Romanticism came from, how that spirit motivated him to push and challenge himself from boyhood ’til death, led him both to egoistic excesses and worthy, epic deeds, and influenced everything from his familial relationships to his time as president to his second and third acts in life.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- What is Romanticism? Why is it essential to understanding TR?

- How Romanticism was baked into TR’s childhood

- How TR made his body as strong as his mind

- The ways that Roosevelt’s father influenced him

- Roosevelt and war

- Roosevelt and love

- Why TR got into politics

- How the West impacted Roosevelt’s worldview and development

- TR’s role as Assistant Secretary of the Navy and how it led to his battle experience in Cuba

- How Romanticism shaped Roosevelt’s politics and time in office

- How TR changed the office of the presidency

- Roosevelt’s second and third acts

Resources/Articles/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Theodore Roosevelt, Writer and Reader

- The Secret of TR’s Greatness

- Theodore Roosevelt On Citizenship

- Roosevelt’s Advice on Reading

- I’ll Make My Body! (AoM Original Comic)

- Becoming Teddy Roosevelt

- The Cowboy President

- The Bully Pulpit

- A Lesson From TR and Taft on Pursuing a Life You Like

- Theodore Roosevelt and the River of Doubt

- TR’s Last War

Connect With H. W. Brands

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Romanticism, not in terms of courtships and bouquets of roses, but as a philosophical approach to life which blossomed in the 19th century embodies many tenets, including a nostalgia for the past, a heroic view of the world, a firm sense of right and wrong, and the idea that an individual can shape his own destiny as well as have an outsized impact on the world.

It is through this lens of romanticism, my guest says, that we can best understand one of the most memorable, influential and legendary figures in American history, Theodore Roosevelt. His name is HW Brands, and he’s professor of history and the author of numerous books and biographies, including TR: The Last Romantic. Today on our show, Bill explains how Teddy Roosevelt was one of the last bearers of the romantic spirit in America, where his romanticism came from and how that spirit motivated him to push and challenge himself through boyhood till death, led him to both egoistic excesses and worthy epic deeds and influenced everything from his familial relationships to his time as President, to his second and third acts in life. After the show’s over check out our show notes at aom.is/rooseveltromantic. HW joins you now via clearcast.io.

HW Brands, welcome to the show.

HW Brands: Delighted to be with you.

Brett McKay: So you are a Professor of History at the University of Texas. And you’ve also written several biographies and the one we’re going to be talking about today is TR: The Last Romantic. There’s been a lot of biographies written about Theodore Roosevelt, but what makes yours unique, and the reason I really liked it, was you make this argument that to understand TR, or one of the ways you’re going to understand TR is to understand that he was a romantic. Now, for those who aren’t familiar with that term, beyond the association of roses and being in love and Romeo and Juliet, how would you describe a romantic worldview?

HW Brands: Well, certainly the way I use it in the book and as I apply it to Theodore Roosevelt, it implies a heroic view of the world, that a person, in his case, Theodore Roosevelt, can have a great and positive impact on things, that there is right and wrong in the world. The romantic view also gravitates toward, backward toward a golden age, thinking that there was a time when things were better and trying to hold on to some of that, but it emphasizes the individual. In the case and in the time of Theodore Roosevelt, a competing theory, a competing worldview was that espoused by the Marxists who said that things… That history unfolds according to great forces, class conflicts, and leaves little room for the individual. The romantic view is just the opposite. The individual can make a difference. And that was the essence of Theodore Roosevelt’s approach to life.

Brett McKay: And what got you thinking that this would be a good way to explore TR’s life, was it this romantic worldview?

HW Brands: Well, part of it came from knowing Roosevelt as President of the United States. I’m a historian of the United States, and so I first came to know Roosevelt as the President, the first president to enter office at the beginning of the 20th century. And so I knew him as this president, he was a young president, he was full of energy, he had progressive notions, so that’s how I knew him. And I also recognized, I knew enough about him personally to see that he was a transition figure, he was born before the Civil War, but he died after World War I. And the United States, American society has never undergone a more rapid, thorough transformation than it did in that period than it did in his lifetime. So he was a child of the 19th century but he was an adult in the 20th century.

And so I could see in… I knew enough about the United States, about Americans, to know that there was this sense that we’re moving from this first era in our history when we were a small country, when we were a frontier nation, to the apex of world power, and Roosevelt was one who embodied that transition. And so he had these ideas and we’re all, in some respects, products of our upbringing, and so he was surrounded by an America, he grew up in America that was rooted in the tradition, well, where the frontier was a big deal, but then it’s a different world that he goes into. And so I get the romanticism from his early times, but I call him the last romantic, and I’m not going to argue that there might be somebody else who would perhaps qualify for that, but it’s a time when the romance is going out of American life.

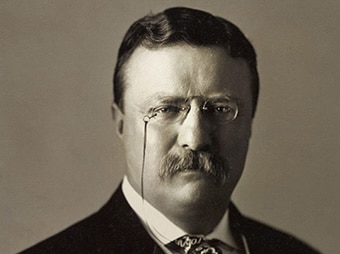

Now, that’s sort of what I knew about Roosevelt from a distance. When I started studying him to write a biography of him, then I realized this romantic view was cooked into his upbringing, because he was a sickly kid. He was often ill of one thing or another when he was young. He was also from a well-to-do family, and so he didn’t attend public schools, or really hang around much with other kids, partly because of the wealthy family, partly because of his illness, and so he spent a lot of time… He spent his childhood in books, and the books that really spoke to him were the ones that spoke about, well, not surprisingly, people, males, in his case, he was a boy, who were strong, who were heroic types, exactly the kind of people he wanted to be.

And at least at that age and in his circumstances, he couldn’t be, but he could escape the confines of his bedroom or his house by reading these books, and he imbibed this thoroughly romantic view of the world of the heroes, and he gradually got a sense that I want to be one of them.

Brett McKay: So this romantic worldview developed in his childhood from his reading of books. Beyond the reading of books, how else do you see that romantic worldview manifest itself in TR as a child? Are there any particular moments that stand out to you?

HW Brands: Well, when he is a young boy, he’s about 10 or 11 years old, his father, whom young Roosevelt, he shared the name of his father, they’re both Theodore Roosevelt. When elder Roosevelt called young Theodore into his office, in his home, and he basically told Theodore Roosevelt, young Theodore, “You need to take responsibility for yourself.” He said, “You have a first rate mind.” The kid was smart. “You have a first rate mind, but you do not have a first rate body, and without the body, the mind can go only so far.” So the elder Theodore was challenging the son. He said, “You must make your body.”

Now, he had the financial resources where he could build a gym on the fourth floor of the house, and he could hire boxing coaches and wrestling coaches and personal trainers and all this. And so Roosevelt took it as his personal mission that he was going to build his body, but there was another angle to this. Because he had spent so much time indoors, he associated the outdoors with this challenge, with a place that he could demonstrate that he was as good, he was as strong, he was as brave as other people, so he started hunting.

Now, the hunting initially was an adjunct to a very… Some people might say nerdy kind of hobby. And that was ornithology. He collected birds. In those days, bird watchers were also usually bird shooters, and the way you develop your collection is you go out and shoot birds, and then you’d mount them and you’d do all this other stuff. So Roosevelt became a hunter, and of course, in his reading of history, many of the great heroes in American history, the Daniel Boone types, they were hunters, and so Roosevelt associated hunting with the kind of manhood that he wanted to grow into, because if you could test yourself against fearsome beasts, then boy, that was a real measure of your courage and of your skill and of your strength, you start out with birds, that’s no big deal.

But you advance from birds to larger animals, to deer, to moose. Moose are pretty dangerous, bears and things like that. So Roosevelt grew into this idea that what he wanted to be, in addition to being strong and smart, was being an outdoorsman, and this in his teen years, and of course, in those days, if you grew up in New York City, you didn’t go hunting in New York City, you had to go some place else. So he would go to Maine, for example, that was the nearest, more or less wilderness area, but like very many Easterners in those days, his imagination naturally flew to the American West, because the West was that part of the country that in some ways was quintessentially American.

It was the part of the country that continually remade itself, it’s what made America different from Europe. America had this frontier, America had this unsettled region out to the West, and of course in the West, there were buffalo, there were grizzly bears, there were the big game of North America, so from the time he was a teenager, Roosevelt began dreaming of, “I’m going to go west and I’m going to test myself against the great beasts of the Western wilderness.”

Brett McKay: Well, that’s that idea of getting back to nature, that’s an important part of romanticism, that you want to get in touch with nature because that’s what you do as a romantic.

HW Brands: And this is especially true in America, because there is this notion, there’s long been this notion of the unspoiled Eden that greeted English colonists when they arrived in the early 17th century, and it’s partly connected to a Protestant theological view of the garden of Eden, the fall of man and all this other stuff, but it also seemed to play out in front of American eyes. And so if they had stayed in England, if they had stayed in other parts of Europe, they wouldn’t have been able to identify with this wilderness because you get very far from the populated east and in fact, the land looks pretty wild, and if you get across the Mississippi and across the Missouri, then it still is wild. There were wild Indians out there, and that seemed to make this connection with this earlier time, and it was possible to imagine, this was the era of the so-called noble savage, the unspoiled person of the wilderness, this bled over into some of the books that Roosevelt has read as a kid, James Fenimore Cooper and The Last of the Mohicans and The Deerslayer and all of this.

And so he had these models in his head of this is what the real America is like, and Roosevelt recognized that a silk stocking kid from New York, that’s not the real America. The real America is the Daniel Boone character, the Davy Crockett, the frontiersmen. And there was a part of him that really wanted to either become that or to test himself against that model to see if he could become that if opportunity arose.

Brett McKay: Alright, so as a child, he exercised, built his body, helped him overcome his asthma, that’s that sort of origin story of his, that’s a romantic thing too as well, but then also he developed his love of nature that you would see throughout his life, and we’ll talk about this later on, this cattle ranching and also his work in conservation and some of his big hunting trips, but you mentioned his father, and you talk a lot about the influence that Theodore Roosevelt Senior had on Theodore Roosevelt. Did Theodore Roosevelt Junior, did he have a romantic view of his dad?

HW Brands: He did probably more than most sons have of their fathers, in part because there seemed to be such a gulf between Theodore Senior and Theodore the younger. The father, as Theodore Junior the younger said, he was the finest man he had ever known. He was strong, he was big and muscular and sturdy in a way that the young kid was not. Now, to some degree, that’s true of every adult father and little boy son. That distinction is always there, but in Roosevelt’s case, as far as he knew, his father had never been sick a day in his life. Now, this would change. His father died of cancer when Roosevelt was in college.

But as a child, he looked at his father as this tower of strength, as this brave person, as this handsome person, as this rock of stability. And young Theodore wanted to be like that. Now, of course, as he grew older, he realized, “Okay, it’s not exactly that. It’s not… My father isn’t everything I thought.” And there was an aspect of this that really sort of intensified Roosevelt’s desire to prove himself, and that was that during the Civil War, which came along when Roosevelt… Started when Roosevelt was three years old, so he was this young kid in New York and he saw the troops marching around New York, he was there in the draft riots in 1863, and so he was really swept up in the war, but he… The war came home, the Civil War came home for young Theodore Roosevelt in a way that it’s not for most people, because his family had divided loyalties.

His mother and his grandmother, his maternal grandmother, who lived with him at this time, they were both from Georgia, and so they were rooting for the South. He had uncles who fought for the Confederacy. And his father, however, was a Unionist, a Northerner, except that his father did not put on the uniform of the Union Army, did not fight. His father didn’t fight primarily because his mother said, “I cannot bear the idea that you might kill my brothers.” So what Theodore Senior did was to take a civilian position, and it was a very responsible, important position. He went from camp to camp persuading the soldiers to allow the War Department to send their paychecks to their wives and their dependants at home, so that they wouldn’t be in want while the fathers were off fighting, so it was a very worthy thing.

He probably did more good for the Union cause in that function than if he had put on a uniform and been a staff, an aide to some general, which is probably what he would have done. But to the young kid and to the teenager he’s growing into, being a civilian during wartime, that was falling short. And when Theodore Roosevelt would hear his age peers tell stories of what their fathers had done during the war, he just had to keep embarrassedly silent, because his father didn’t have any war stories. And Theodore Roosevelt’s sister, he had two sisters, and his younger sister recalled that he made a silent pledge, Theodore Roosevelt made a silent pledge in some way to make up for this one chink in his father’s armor, this one deficit in his father’s resume, and that was, he was going to prove, the younger Theodore, the son, was going to prove that the Roosevelt men were brave. He was going to go to war and show his courage under fire in a way his father had not.

And so the relationship with his father was one that drove even further Roosevelt’s notion that I have to be a hero, or I have to prove my courage, I have to demonstrate that I’m strong and brave and able. The fact that his father died when Roosevelt was in college meant that the adult son never got to measure his father sort of adult to adult, ’cause his father was gone. In most cases, when an adult child grows up and then comes to know the adult father, there’s a kind of equalization, there’s a kind of… Some measurement that, “Alright, I understand that you can have your flaws, we all have flaws,” and so on. With Roosevelt no, his father dies, and so he is deprived of the ability to develop that relationship, show his father is this hero with one little Achilles heel, and if I can somehow make up for that, then my father will be perfect and he can remain perfect in my vision. So this is part of what drives Roosevelt as he becomes an adult.

Brett McKay: And that would probably play an influence in his involvement in the Spanish-American War, and we can talk about that here in a bit, but before we do, so this is… We’re talking about… We’re up to him being a young man, he’s hunting, he’s gone to college. You describe him in college, he was sort of an odd duck at Harvard, he was boxing, but also he wanted to recite Tennyson while he was boxing, and people thought it was kind of weird, but he ended up flourishing. He gets out of college and he marries his first love, this girl named Alice. Let’s talk about his family life. How did TR’s romanticism influence his relationship with Alice, and then how did his romantic worldview shape how he responded to her death?

HW Brands: Yeah, so this is a case where sort of the romantic worldview coincides with what people often think of when they talk of romance, Valentine’s Day and so on, because Roosevelt indeed was an odd fit at Harvard. And there are a lot of odd fits at Harvard, but he wanted to be an athlete, he wanted to be the star of the football team, he just wasn’t coordinated enough. But he tried, and so he was stubborn, he was dogged and he realized that he could succeed at certain sports like boxing where, okay, if you just keep standing and stay in there, wrestling, if you can just… If determination will conduce to success, then you can be a success. So he was that way, but he wasn’t a particularly well-liked person, he wasn’t most popular until, until… Well, when his father died, his father left him a sizeable fortune for a young man.

And so all of a sudden now, he can throw the parties and he can be the one who has the resources that bring other people around. So in his last couple of years at Harvard, he’s much more of a success, and it may be… I don’t know if it goes without saying, but it certainly was true that he became more eligible in the eyes of young women, including one Alice Lee over whom Theodore Roosevelt fell head over heels for her. Now, this is kind of interesting, because Roosevelt had had a boyhood girl friend, Edith Carow, she was a friend of the family, a friend of his sisters.

And Edith certainly thought that there was some kind of understanding she had with Theodore when he went off to college. They were too young to get married, but in her head anyway, marriage was in prospect. And then he forgot all about her when he fell for Alice Lee, and Alice Lee was this young, beautiful, charming girl. And at first, Roosevelt thought that, boy, she’s out of my league. But he was persistent in wooing her, as he was persistent in a lot of things, and he finally proposed and she accepted, and they were married. And Roosevelt thought, “Oh, my gosh, this is the greatest thing could ever happen to me.”

And he was in a state of romantic bliss and he… So this is going on, and he’s trying to figure out what to do with himself after college because he was wealthy enough that he didn’t have to work, but he had to do something. So he shocked members of his family by deciding to go into politics. Now, for somebody of Roosevelt’s class and station, this was an unusual choice, because politics, certainly in New York, was not what members of the elite did. The elite folks, they counted their money and they circulated at their clubs, but they left the grubby business of governing to other people, to the striving Irish-American types, to the ones who don’t have any other way of getting ahead.

But Roosevelt conceived this idea that he wanted to be part of what he called the governing class. Now, to some degree, I suppose this is because Roosevelt by now was insisting on always challenging himself, and it wouldn’t be any challenge just to fill his time going to his clubs and going on fox hunts and doing stuff like that. No, no, he needed a challenge, and politics was where he could make a challenge. Well, he got elected primarily because he was wealthy and could afford the bar tabs for all of his followers, and he got elected to the New York legislature.

And for a couple few years, he thought his life was golden, because he would go back and forth from his home in New York up to Albany when the legislature is in session, ride the train up and he’d write letters, love letters home to Alice, and everything was great. And then when Alice became pregnant and they were going to have a child, boy, this was even better. But tragically, Alice died. Alice died giving birth to their daughter, and it just so happened that on the same day, and it happened to be Valentine’s Day of all days, his wife died and his mother died, on the same day in the same house because Alice was living with the mother when… In the final stages for pregnancy. And so there’s this double blow on Roosevelt.

Now, to be honest, Roosevelt felt much more deeply the death of Alice than of his mother. He was fond of his mother, but the father was the parent that really dominated Roosevelt’s mindset. But when Alice died, then Roosevelt felt as though, in fact, as he wrote in his diary, he put a big black X over that day in his diary and said, “The light has gone out of my life.” And this was exactly the way you would expect the romantic hero to respond to the death of his true love. And Roosevelt thought that I will never feel love again.

And so what he did was, he fled. He fled the East, he fled politics for the West. Now, it just so happened that the summer before, he had gone out to Dakota territory to hunt buffalo. He had always been wanting to hunt the biggest game of North America, so off he went. And while he was out there, he was very impressed with the region along the Little Missouri River and with the people he met out there. And Roosevelt, like very many Easterners, thought that Westerners, Western men were the authentic men of the country. This was the real America, and he wanted to be like them. So he had enough money that he decided to buy what amounted to a cattle ranch. He wrote a check for, I think it was $14,000, to this guy he had just met several days before, and said, “Okay, I trust you, basically, ’cause you’re an honest Westerner and you wouldn’t cheat me. And now go buy me the cattle, get this thing set up.” And so off he goes back East.

And then, and then when his wife dies, he has this refuge to which he can go, a refuge in the West. And he finds solace for his heart in the wilderness of the West and he writes about riding through the badlands of Dakota territory, these strange, weird landscapes that they were so strange that they did provide this kind of other-worldly solace. They were balm to his soul. And to Roosevelt, this… The West became this place to which he could go when he needed to get away from the cares of the East.

Now, this had been in the collective American mindset for generations, the West was where we can go when things go wrong in the East. Now, as a matter of fact, most Easterners didn’t go West, but the idea that they could, that was really important, and it’s critical for Roosevelt’s emotional and political development, and for that of the country. It was at just this time that the frontier is vanishing. Enough Americans have moved West so that in the 1890 census… So Roosevelt’s wife dies in 1884, Roosevelt’s out there in the 1880s. But in 1890, the director of the census says, “You know what? There’s no longer any frontier because the settlement is scattered all across the West.”

So there’s this idea that the frontier is vanishing, and this important aspect of America’s psychic life is disappearing as well. But Roosevelt believed that there was something special, that he was able to get there before it went away, but it became a very important part of not only of his life, but of the identity that he had created for himself. He was an Easterner by birth, but he was a Westerner by adoption and a Westerner in spirit.

Brett McKay: So his first wife dies, Alice Lee, and he had this romantic ideal of love that, okay, if your first wife dies, you don’t remarry, and he told his sister that, “I’m not going to remarry.” Well, he ends up remarrying, and it was Edith Carow, his childhood friend. And he even wrote letters to his sister, “You know how I feel about getting remarried, but yeah, I just feel this is the right thing to do.” And it’s sort of like this whirlwind wedding kind of under the radar. Then he becomes this family man. Is there anything we can learn about TR’s romanticism through his family life?

HW Brands: Well, what we see with Roosevelt is this sort of full-blown romanticism of his boyhood that continually runs up against reality, because romanticism is at its heart an unrealistic view of the world. Now, we all have certain unrealistic views of the world and they have to be reconciled with reality at times. And Roosevelt was able to retain some of these, but when he re-encountered Edith Carow, he realized that, well, he was attracted to her. And as you suggest, he felt guilty about it because you’re only supposed to have one true love, those romantic Knights of the Round Table and all this other stuff, this one true love for each of us.

And he talked about how he didn’t know what he would do should he be fortunate enough to get to heaven after he died, because he’d have to explain to Alice that he had been unfaithful to her after her death by marrying Edith. Anyway, but he does, and they have children, and the kids aren’t really part of Roosevelt’s romantic vision, but one of the things they do is they make Roosevelt really attractive to voters and because… Okay, here’s this family man, and he’s young. Roosevelt was remarkably young in all of this stuff, he’s going to be… When he does become president, he’ll be the youngest president in American history till then, and since then.

But the fact that he had kids, it demonstrated a kind of vitality. Often, the virility of someone is measured by, okay, did you have kids? And he had bunches of kids, he had six kids, and the kids were all running around. And so while he was in politics, even when he got to the White House, he was the first president, I think since Lincoln, who had young kids in the White House. And this was, this was fantastic for a lot of people because they tended to look on politicians as these old guys in stuffy suits. And Roosevelt wasn’t stuffy, and he had children running around, the children were doing what kids did.

So some of Roosevelt’s romantic view, part of it makes him appealing to the American public because they have a romantic view too. But other things that made him appealing were just the fact that he seemed to be this honest guy, and he had kids and he paid attention to the kids and he used to play with the kids and he would let the kids have pets, and sometimes they would bring horses into the White House. There’s one case where they brought a small horse in the elevator of the White House.

Now, the kids were up to what kids do, and so Roosevelt became… And in decades later, when John Kennedy became president and his two cute kids, they made Kennedy and Jackie, his wife, all that more appealing because, “Aww, what cute kids.” And they said the same thing about Theodore Roosevelt and his children.

Brett McKay: So we talked about after he got involved in politics early on in his young adult life, fled it for a little bit, then got back in, and he was primarily involved in New York politics, but eventually he gets… The National Party catches, they seize Theodore Roosevelt like, “This guy’s got potential.” And he finds himself Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and he’s in a position now where he’s able to have some amount of influence on world affairs, and it allows him… And kind of the way you describe it, allows him to start making up the deficiency that his dad had of not fighting in war. Can you tell us about his involvement as Assistant Secretary of Navy and how that eventually may have led up to the involvement of him charging up San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American war?

HW Brands: Sure. So Roosevelt was really talented guy, and people recognized the talent in Roosevelt, but he was basically in the wrong political party because he was of a reformist frame of mind at a time when the Republican Party was growing more conservative by the year, by the decade. So he was an odd fit, and he was also this… Well, at least before he goes off to war, he was somebody who couldn’t get elected outside a narrow circle. So Roosevelt wanted to get back into politics, but the Republican bosses didn’t like him, and so they wouldn’t give him the nomination.

So what he did was he went back into politics, but as an appointed official rather than an elected official. He couldn’t get elected, but he could get appointed and he was good at what he did. So he was a civil service commissioner, then he was on the New York Police Board, and while he was in those positions, he would campaign on behalf of the Republican candidates for elective office. And he campaigned in 1896 for William McKinley, and was a stout campaigner for McKinley and when McKinley won, he was in line to get a job. This is the way people get appointed jobs in national administrations, and Roosevelt, well, he dreamed, “Oh, maybe I’ll be Secretary of State.”

He was very interested in foreign affairs, but that was above his grade, but instead he got the job of Assistant Navy Secretary. Now, this was… Assistant might sound relatively small potatoes, but for Roosevelt, it wasn’t, in part because the cabinet secretary, his boss, was somebody who wasn’t particularly interested in running the office, and so he let the daytime running the office go to Roosevelt, but also because Roosevelt had grand ideas about what the United States ought to be doing in the world. Roosevelt looked upon the United States as a bigger version of himself, and just as he looked for a chance to prove himself, to prove himself strong and brave and upright and all this, he looked for opportunities for the United States to prove itself strong and brave and upright.

And when a rebellion against Spanish colonial rule broke out in Cuba in 1895, Roosevelt was all for American intervention, and he kept, as Assistant Navy Secretary, he kept pushing William McKinley, his boss, the President, saying, “You gotta intervene, you gotta intervene.” And finally, not by himself, but in conjunction with other people, Roosevelt talked McKinley into declaring war against Spain, into intervening in the Cuban uprising against Spain. And Roosevelt… Well, a lot of people thought the United States ought to do it to relieve the suffering of the poor Cuban people.

Roosevelt didn’t really care that much about the poor Cuban people, what he cared about was the opportunity for the United States to step up and play the role he thought it ought to play on the world stage, and he was going to help this happen. And so while he was Assistant Navy Secretary, he gave orders when his boss was out of the office. One Friday afternoon, his boss had gone home, he sent orders to the Commander of the American Pacific Fleet, they called it the Asiatic Fleet in those days, George Dewey. Said, “In the event of war with Spain, go straight to the Philippines and attack their fleet there.”

“The Philippines?” one might say, “The Philippines?” And people did say later, “What, the Philippines?” Well, the Philippines were another Spanish colony. So if the United States went to war with Spain, then the Philippines would be fair game. So Roosevelt’s order went out and when the war came, that’s exactly what Dewey did, and the United States seized control of the Philippines and made… Eventually, at the war’s end, made the Philippines an American colony.

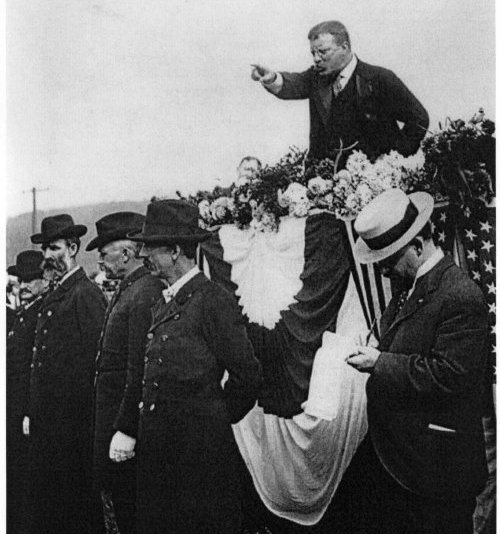

But meanwhile, meanwhile, Roosevelt did something that should have boggled the mind of just about anybody else and should have boggled his own mind, if he hadn’t been so wrapped up in proving that the Roosevelt men were brave. His sister and other people who knew Roosevelt, said, “Roosevelt.” This is when Roosevelt was a relatively young man. He’s still in his early 30s, mid-30s. And they say, “Roosevelt, he just wants a war. He doesn’t care who the war is against, he wants a war, so he can go to war, so he can stand up under enemy fire and show that he’s brave. And basically to atone for his father’s failure in the Civil War.”

So when the war comes, the war that Roosevelt had been instrumental in bringing on, Roosevelt quit his job in Washington so he can go fight, he can join a cavalry regiment, and can go test himself under fire. And he does, he goes off to Cuba and he performs quite bravely, quite gallantly in the battle for San Juan Hill. And the enemy shoots at him and people get killed on either side of him, it was kind of dumb luck that he himself wasn’t killed, but he wasn’t. And ever afterwards, Roosevelt described that battle as his crowded hour. And strikingly, up to that time, Roosevelt was what could fairly be called a warmonger. He wanted war. Other things being equal, he wanted a war.

After that… Nope. Nope. In fact, after that, Roosevelt eventually would win the Nobel Peace Prize because the war had served his purpose of proving to himself that he was brave. He didn’t flinch under fire. And once having demonstrated that, he didn’t have to do it again. But he came home a military hero. And one of the reasons he came home a military hero was… Well, in the army, during the war, he wrote a memoir. He sent back weekly, monthly reports that were published in Scribner’s Magazine and then gathered as a memoir called “he Rough Riders. And so he told his own heroic story of his role in the Spanish-American War. He came home to a hero’s welcome.

Brett McKay: And basically it catapulted him to the national stage. It’s probably why… Well, he became vice president and he became president because the president was assassinated. But after that point, he was able to get elected on his own. Yeah.

HW Brands: Okay, so in fact, his… Although he came home a hero, there were lots of heroes from the war and there is no clear path for Roosevelt to the White House. In fact, he was chosen by those Republican pols, Republican political bosses in New York, to replace a corruption-stained candidate for governor. They needed a new governor, they thought this Roosevelt character, he’ll be a good stand-in. And so he accepted and he got elected. But everybody thought that was as far as he would go. In fact, he soon ran afoul of his sponsor, Tom Platt, the Republican boss in New York, because he was too independent-minded. Roosevelt realized something. Maybe he was chosen by Tom Platt to be the nominee, but the voters voted him governor.

And so the next day, he wakes up and said, “I’m governor, Tom Platt. You’re not.” And so he started to demonstrate that he would govern as he wanted to do. So Platt goes, “What am I going to do with this guy? He’s not the person that I wanted to get elected, at least it turned out not to be the one.” So Platt engineers his nomination to be vice president, thinking, “Okay, going to kick him upstairs, get him out of my hair.” Because in those days, the vice presidency was almost like a witness protection program. People went into it, never came out. You never heard of them again, except, except on those couple of cases, and there had been two cases before, three cases before this, where presidents had died or been killed in office.

And people on the national Republican stage said, “Oh, God, we sure hope this doesn’t happen to McKinley because then Roosevelt will be president.” He was the last person they wanted to be president. That’s exactly what happened. William McKinley was assassinated and Theodore Roosevelt became president. And he told his friend, Henry Cabot Lodge, “It’s a shame to have to enter the White House this way, but here I am. So now I’m going to do what I want to do.”

Brett McKay: And I think you make the case that throughout his presidency, his romanticism is what… That shaped how he approached the office of the presidency, and it fundamentally reshaped how Americans think of the office of the president.

HW Brands: Well, I wouldn’t say that it reshaped how Americans view the office because romanticism was sort of a dwindling resource in American life. And its one of the reasons I call Roosevelt the last romantic. And there’s not a president after him that follows that model. And Roosevelt, a romantic, at least as I use it, is someone who looks back, but Roosevelt was not… There was more to Roosevelt than that, he looked forward. And Roosevelt could use that romantic strain in himself and in others to his advantage, but he wasn’t bound by that. And so, as I said, Roosevelt told Henry Cabot Lodge, “It’s a shame to have to become president this way.” He would rather had been elected by the people. But he hadn’t, but he was still president, he was going to do what he was going to do.

And he was going to yank the United States into the 20th century, because Roosevelt believed, for example, that big business had gained too much power in American life, that capitalism had run away with American democracy. And that just as capitalism had bulked up during the last decades of the 19th century, Roosevelt was going to bulk up American democracy. One of the first things that he did was to call in JP Morgan, who was the great financier and the orchestrator of various mergers that gave rise to these big trusts, trust was the term for monopoly in those days.

And he told Morgan that he was going to break up Morgan’s most recent trust, a railroad trust called Northern Securities. And Morgan was outraged, wait a minute, you can’t move the goal posts on us now because this was fun.” And Morgan said, “Look, if you got a problem with this, you know, just send your guys to my guys and we’ll talk it over,” and Roosevelt said, “That’s not the way we do it. America’s democracy runs the show here, I am the president, the people elected me, nobody like to do to anything, JP Morgan. And so, you’re going to play by the rules that I established.”

And furthermore, Roosevelt was going to push the United States onto the world stage. It already came in partly from the push that he gave in triggering the war against Spain, but the United States under Roosevelt really stepped out and stepped into world affairs, he served as a mediator between the Russians and the Japanese in the war those two countries were fighting, and for that he won the Nobel Peace Prize. But Roosevelt had this grand vision for the United States, and it was a vision that there was a certain romanticism to it, but it certainly was not confined to that, and it wasn’t backward-looking at all, it was very forward looking.

Brett McKay: No, yeah, I would say that idea that a single man can change the world, a single individual could have influence on the world, he expanded… Like before that, the office of the president was… There was a very limited view of the office of the president. It was like, okay, the legislature takes care of everything. Roosevelt said, No, I’m going to use as much power as I have, and I’m going to do things, like he did the Panama Canal. And he said, well, Congress is debating that while here I am in a back hoe, digging the Panama Canal. He saw opportunities to take control or take charge, and he just took it by the reins.

HW Brands: Roosevelt was a complex individual, and he was also a very resourceful individual in finding arguments for positions he wanted to take for reasons that transcended the arguments. So Roosevelt was one who believed in the power of the presidency; actually, he believed in the power of himself. He was unusually self-confident, and I’m not quite sure where this comes from, being the eldest child, the eldest son, excuse me, is probably part of it, being named for your father maybe contributes to that. But he took the view that, well, if the Constitution doesn’t say I can’t do it, then I’m going to do it, and people can try to stop me.

So Roosevelt had this idea that the United States… And he did believe that the presidency, the president embodied the United States in a peculiar way. Now, some of this was simply Roosevelt, but some of it was a consequence of changes in the nature of America’s position in the world, changes in things like technology. But in the first place under the US Constitution, the executive branch, the presidency, takes second place to Congress, the legislative branch, it’s Article 2 in the Constitution after Article 1 dealing with Congress. And through the 19th century, that was the position that most presidents took. The executive branch is called the executive branch because it executes the will of Congress.

But Roosevelt thought it should be more active than that, he thought it was necessary, especially in a world where foreign policy plays a large role, because Congress is this very large committee and it can’t make decisions very quickly. In domestic affairs, that’s not a particular drawback, but in foreign affairs, that’s fatal. And Roosevelt recognized this. Roosevelt also recognized with the emergence of modern communications technology, in particular with a modern mass circulation press, all these newspapers, they have to sell lots of copies of their papers to cover their costs, they need a riveting story.

And it’s a lot easier to write a story, a more dramatic story about one person about one man, forceful man, than it is about the committee of several hundred that Congress consists of. And then there’s a fact of Roosevelt had these children and they were a story in themselves, so Roosevelt galvanized the attention of the American political culture. Roosevelt is the first truly modern president in that regard. Until Roosevelt, the president was not usually the focus of American political attention. At certain times, during the Civil War, of course, with Abraham Lincoln, but in the 20th century, the president is going to be really at the center of everything in American politics, and it’s largely because the Theodore Roosevelt set the model there.

Brett McKay: So Roosevelt described his time as the president, said he had a good time. He genuinely enjoyed being president. There’s some presidents that they described like I hated it, it was like the worst job I ever had, like Taft, I don’t think really particularly enjoyed being president. What happened after his presidency, how did his romanticism keep pushing him when he didn’t have anything to do?

HW Brands: So part of Roosevelt’s problem in this regard was that he became president too soon. He became president when he was 41, and that’s young for such responsibility, but of course what it meant was that he’s going to, not even going to be 50 when he leaves the White House. So what’s he going to do for his second act? And he thought, okay, well, he hand-picked his successor, William Howard Taft, and so he thought the Taft saw eye to eye with him on important issues and so, okay, good, I got my guy in there, so now I’m going to go and give them a chance to form his own presidency, to make his own reputation.

And off he went to Africa, which is of course where something like Theodore Roosevelt would go. He had basically hunted all the big game there was in North America, so where is even bigger game? Ah, there are elephants in Africa. So off he went to Africa, it was a safari that he’d always wanted to go on, and now he had a chance, and he was able to do it under the auspices of science. Roosevelt was a conservationist. Now, to modern sensibilities that might seem weird. Roosevelt slaughtered more animals in his life than all but probably a handful of other people in his age.

So what does that have to do with conservation? Well, in fact, Roosevelt helped found one of the first and most important conservation groups, the Boone and Crockett Club in America, and they conserved natural resources so they would have something to hunt in the future, they didn’t want to kill all the animals. And so it wasn’t uncommon for Roosevelt to go off to Africa and shoot elephants and rhinos and other big game for the purposes of science and conservation, because he made sure that the elephants were sent back to the Museum of Natural History and stuffed and put on display there. And so people can say, “Oh, that’s what an elephant looks like,” and this is of course, before television or anything like that.

And so, yes, he could do it for science, he could do it for conservation, but he could also do it because there was still in Roosevelt that itch, that, “Okay, I have to prove myself.” This had become part of Roosevelt. So he had to keep proving himself. He went off to Africa, and he proved himself by standing there in front of a charging elephant and killing it, not himself getting killed, not flinching. That was good. But then he came back to America, he finally came. He spent a year in Africa nearly and he had to come back, and what’s he going to do now?

And some people who were unsatisfied with the way McKinley had handled the presidency began whispering in Roosevelt’s ear, “He’s just not doing what you thought he should do. He’s betraying you.” And it didn’t require too much whispering to get Roosevelt to say, “You know what, I need to take over again.” In those days, there was not a constitutional ban on third terms, and technically it wouldn’t have been a third term anyway, ’cause he had inherited the first term, but in any event, he decides to run again. Now, this was perhaps Roosevelt at his least admirable, because he talked himself into believing that his country needed him, the progressive movement needed him.

Really, it was Roosevelt needed something to do, he needed a challenge, and the challenge was to run for president as a third party candidate. Third parties had never done well in American politics. Roosevelt did better than any third party candidate before or after, but he failed, he didn’t get elected and he destroyed the elective political career of William Howard Taft. He split the Republican Party, costing Taft and himself both the election which went to a Democrat, Woodrow Wilson.

So that’s what he did, and then having lost that one, he’s got to do something else now. He’s still, still a relatively young man. He’s in his early 50s, and what’s he going to do? Well, he decides to go on a trip of exploration into darkest Amazonia. He’s going to follow this river from its headwaters, people knew about the headwaters, and they sort of knew what they thought were where the lower part of the stream, but the part in between was unknown. It was called the River of Doubt, and Roosevelt was going to join this expedition and go down and explore this river.

I mean, after hunting big game in Africa, how are you going to top that? If you’re going to be the explorer type, the one who discovers great things… Well, Roosevelt had never really discovered anything, but this is his chance. Now, when you get to this point in Roosevelt’s life, you start to think that there must be something more about this. And one of the things that I at any rate concluded about Roosevelt is his activism, his activity, his inability to slow down, his inability to just relax and absorb what’s around him. This derived from, I think, from a certain kind of background… Well, in our day, we call it depression, that he was dealing with.

Depression ran in the Roosevelt family. There were suicides in the family. And Roosevelt at a relatively young age quoted the Roman writer Horace who said black care can never catch a rider who gallops fast enough. And it seemed to me that Roosevelt was doing that galloping his whole life. And so he always had to find something else. There was another thing, that just before he was married, just before he married Alice Lee, who became Alice Lee Roosevelt, he underwent a physical exam. This was not uncommon in those days, and especially for somebody who had had this background of illness like Roosevelt. And as Roosevelt told it later, the doctor heard an irregularity in his heartbeat. There was a heart murmur or an arrhythm or something, and the doctor suggested that Roosevelt ought to take life easy because if he strained himself too much, he might just fall over dead.

But Roosevelt concluded, “Nope, nope, I’m not going to live that way. I’m going to live my life to the fullest, and if I die before the age of 60, so be it.” So in going to the Amazon, one can look at Roosevelt’s actions and think, “Okay, he doesn’t know what to do with himself.” There’s really no act after the presidency in American life that would suit Roosevelt. So first, he went to Africa. If he had been killed by a charging elephant, he would have been okay with that. And I think that part of him thought, “Well, okay, if I die of fever in the jungles of Amazonia, I’m okay with that. What a way to go out.”

And in fact, he nearly did die of fever in the Amazon, but he survived and he came out of that. And he still has to figure out what to do, but he got out just in time for World War I to break out. And he decides, “Yes, that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to reprise my actions in the Spanish-American War, but this time on a bigger scale.” So instead of raising a regiment of volunteers, he proposes to President Woodrow Wilson to raise two divisions of volunteers, and he goes to the White House and says, “This is what I want to do.” And Wilson says, “No.” And for Roosevelt, in fact, at one point, somebody told Roosevelt, “Aren’t you kinda old to be volunteering to go off and fight in France?”

But Roosevelt said, “I cannot think of a better epitaph than Theodore Roosevelt died on the battlefield in France.” So it’s almost as though that romantic streak in Roosevelt was stronger than ever. He was going to go down to a hero’s death. The last thing Roosevelt wanted was to get old and frail and just die the way people died in ordinary life. He wanted to die a heroic death if he died at all.

Brett McKay: And well, he did die eventually and it’s probably…

HW Brands: He did die.

Brett McKay: Yes, correct.

HW Brands: He didn’t get to go off to France, but he did die of a heart attack and it came right after his 60th birthday. And it was about the time that his doctor said, “You know, you might die by that time.”

Brett McKay: Bill, what do you hope people when they finish your book, what do you hope they walk away with thinking or chewing on after they finish your book?

HW Brands: That there is a place for a grand vision of the world in causing people to attempt great things. And Roosevelt is one of the most… I’ll call him laudably ambitious figures to hold the White House. He set high standards for himself. And he came… He did pretty well in living up to them. To some degree, those high standards were part of this unrealistic view of the world, this romantic view of the world. So that can… Even an unrealistic view of the world can have worthy consequences. But Roosevelt also was very shrewd while he was president in keeping his romanticism in check.

And this is, if there’s one thing to keep straight about Roosevelt, Roosevelt as an individual was separable from Roosevelt the president in a greater sense than is often in the case. So I said that Roosevelt, before he became president, was this warmonger. Roosevelt had several opportunities while he was president to push the United States into war, but he refused. So Roosevelt understood that the president is this different, not necessarily a different person, but he has a different function than an individual. So before… And now, as from the standpoint of the biographer, the presidency is the boring part of Roosevelt’s life, because presidents do what presidents do.

Before Roosevelt was president, he’s this really colorful character, and you can see his personal and career trajectory rising; after he’s president, you can see the trajectory falling, but he’s still this very interesting figure, a very… Does dramatic stuff. While he’s president, he’s kind of boring. But Roosevelt understood the purpose for that. What you don’t want is somebody who as president is trying to play out these inner struggles, these inner visions and all of this other stuff. So Roosevelt is a really good example of how you can be this very interesting character, you can really be a character and still be a really good president. So in that regard, Roosevelt is kind of a model of how to keep the personal separate from the professional, to the advantage of both.

Brett McKay: Well, Bill, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and the rest of your work?

HW Brands: Well, the book is available everywhere books are sold. The book was published in the 1990s, but it’s in most bookstores if you go there, and certainly it’s available on Amazon, TR: The Last Romantic, and next to that book, you might find some of the other biographies that I’ve written.

Brett McKay: Well, fantastic. Well, Bill Brands, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

HW Brands: Good to talk to you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was HW Brands, he’s the author of the book TR: The Last Romantic. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about the podcast and his book at our shownotes at aom.is/rooseveltromantic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AoM podcast, check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher premium. Head over to Sticherpremium.com, sign up, use code manliness at check-out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast.

And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to gives us a review on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member, who you think could get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to the AoM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.