Our ancestors were able to navigate long distances, find water, and even predict the weather simply by looking at their environment. My guest today says we still have this nature instinct inside of us and with a little practice, we can revive it.

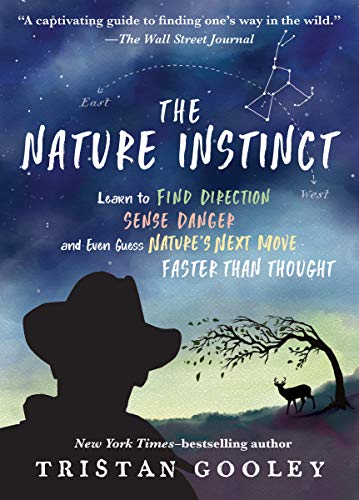

His name is Tristan Gooley, he’s an outdoorsman and author, and his latest book is The Nature Instinct: Learn to Find Direction, Sense Danger, and Even Guess Nature’s Next Move—Faster Than Thought. Today on the show we discuss how humans have the ability to simply look at something in nature and immediately see direction, time, or weather conditions. While modern humans have lost this ability, Tristan makes the case that with some practice, anyone can re-learn it. We then discuss how learning how to read nature intuitively makes us more engaged with our surroundings and able to see more significance in our environment. Tristan then shares signs to look for in nature to anticipate animal behavior, find water, and predict the weather. After listening to this show, you’ll never look at squirrels the same way.

Show Highlights

- Developing your intuition in the outdoors

- How pattern recognition plays a part in our relationship to nature

- How long does it take to re-learn this “nature instinct”?

- What hunting and animal observation can tell you about nature

- What’s the benefit of learning these skills?

- How using the nature instinct can help you inject more meaning into the world

- What is umwelt?

- Recognizing various animal “highways” and what they can tell us

- Predicting the weather

- Finding water in the wild

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- How to Read Nature — my first interview with Tristan

- 15 Constellations Every Man Should Know (And How to Find Them)

- Thinking, Fast and Slow

- How to Get Your Kids to Love Nature

- How to Track Animals

- 4 Ways Nature Restores Your Vigor

- Umwelt

- 7 Ways to Love the Place You Live

- How to Find Water in the Wild

- 22 Old Weather Proverbs That Are Actually True

- Fair or Foul? How to Use a Barometer to Forecast the Weather

Connect With Tristan

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Brilliant Earth is the global leader in ethically sourced fine jewelry, and THE destination for creating your own custom engagement ring. Get a FREE surprise gift when you buy an engagement ring and shop all their selections at BrilliantEarth.com/manliness.

Saxx Underwear. Game changing underwear, with men’s anatomy in mind. Visit saxxunderwear.com/aom and get 10% off plus FREE shipping.

Indochino. Every man needs at least one great suit in their closet. Indochino offers custom, made-to-measure suits, dress shirts, and even outerwear for department store prices. Use code “manliness” at checkout to get $30 off your purchase of $399 or more. Plus, shipping is free.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay:

Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Our ancestors were able to navigate long distances, find water, and even predict the weather simply by looking at their environment. My guest today says we still have this nature instinct inside of us, and with a little practice we can revive it. His name is Tristan Gooley. He’s an outdoorsman and author, and his latest book is The Nature Instinct: Learn to Find Direction, Sense Danger, and Even Guess Nature’s Next Move Faster Than Thought.

Today on the show, we discuss how humans have the ability to simply look at something in nature and immediately see direction, time, or weather conditions. While modern humans have lost this ability, Tristan makes the case that with some practice, anyone can re-learn it. We then discuss how learning how to read nature intuitively makes us more engaged with our surroundings and able to see more significance in our environment. Tristan then shares signs to look for in nature to anticipate animal behavior, find water, and predict the weather. After listening to this show, you’ll never look at squirrels the same way. Be sure and check out our show notes at aom.is/natureinstinct. Tristan joins me now via clearcast.io. All right, Tristan Gooley. Welcome back to the show.

Tristan Gooley:

Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay:

So we had you on last year or a few years ago, it’s been a while, to talk about your book, The Lost Art of Reading Nature Signs. You got a new book out, The Nature Instinct: Relearning Our Lost Intuition For the Inner Workings of the Natural World. How is this book, The Nature Instinct, different from some of the previous work you’ve done and writing you’ve done about reading nature, and how to figure out direction just by looking at a hill. What’s the big idea in The Nature Instinct?

Tristan Gooley:

What I’ve done is taken my general approach, which is that everything outdoors is a clue, and just look to the ones that if we practice using them a little bit, give us the sort of reading of our surroundings that I believe our ancestors had and, which I think I see in indigenous cultures to this day.

Brett McKay:

So the idea is, so like before, we went through some of the tips and some of the ideas in the last podcast, so the idea in the previous book is like, okay, you’ve looked for the way the tree, a tree is pointed or the leaves are growing on a tree, and you can deduct the direction that, which way is north, south, east, west. In The Nature Instinct, the idea is you’re going to skip beyond the deliberation where you can just look at the tree and see north.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah. What happened was a couple of things happened to me very personally. I was teaching people how to use what I call the check effect; the shape of the branches to find north and south in a tree. They grow close to horizontal on the south side, and closer to vertical on the north side. And lots of people in a group could see this, but one or two people couldn’t and I thought, “That’s odd.” And I showed them a couple of techniques to spot these things; like if you squint, it filters out small details and you see the bigger shapes and patterns, and we got there in the end.

And round about that time, I was going on a car journey and a tree announced direction to me. Now, there isn’t language that does this sensation perfect justice, because as we’ll discover as we discuss it, this is stuff that’s going on quite deep in our brains; deep in a historical sense; what used to be called our lizard brain. And this was all quite strange and new to me, but I had noticed quite a few years ago that very occasionally I would see direction in the night sky. So what happens for a lot of people is you can show them how to spot what we call the Plow here in the U.K. and what you guys call the Big Dipper, and you use that to find the North Star. And it’s very methodical and it’s straightforward, and once you’ve done it a few times, it’s almost child’s play.

But what happens after doing it maybe a few times a week over a month? There comes a moment where you will see north in the night sky just in the way that you can see direction in trees. And this book, The Nature Instinct, is really the patterns that allow us to do that, which, if you talk to any indigenous people and you say to them how did you do that thing in the wild; and it can be pretty much anything; what you tend to find is that they find it extremely hard to describe what they’re doing. In the same way that if you ask somebody who’s been riding a bike for 20 years or driving a car for 50 years how do you do that, it’s quite hard to articulate because it’s so deep within our brain.

Psychologists call it the difference between fast and slow thinking, and the Nobel Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman, wrote an excellent book looking at that area; mainly written to do with economics, but exactly the same type of psychology applies, and from my perspective applies more originally to the outdoors.

Brett McKay:

So with The Nature Instinct, it’s this idea of intuition, this fast thinking. And it’s all about pattern recognition; it’s something that you develop with just more and more experience. An example you gave of sort of modern Western civilized cultures of the fireman who went into a building, and he went in without even really knowing analytically why they need to get out of that building, he said we got to get out of here. And as soon as they got out of there, the building collapsed.

Tristan Gooley:

Yes, and again the mechanics of that were very hard for that individual to explain immediately afterwards. But after, because it was such a key thing and the people researching it, the psychologists researching it really needed to know what had happened, that I believe they spent quite a lot of time getting to what was actually quite simple clues, and it was to do with temperature from below and sound not quite fitting the expected pattern. So they were expecting a fire on the same level as them, and that would present certain sounds and certain temperature sensations, and those two things didn’t match, which gave a feeling, and not a … it’s not like a sort of crystal clear report that comes through that says the fire’s not on this level, it’s below you. It’s much more that sensation that we’ve all had, which is something’s not right. And in a fire situation, something’s not right is akin to the survival feeling that we can all get if you’re outdoors and there are dangerous predators in the area. You’re much more likely to be tuned to those sorts of signs.

Tristan Gooley:

But we do, we haven’t lost any of this ability; we’re just focusing it in different areas. So if you’re in a car and the driver in front of you drives at all erratically, that’s something we’d pick up these days. But it’s exactly the same, exactly the same skill, and that’s why teenage drivers’ insurance costs more than people who have been driving for 20 years. It’s because when you’ve been driving 20 years, you spot these patterns. And when you’re past 18, you’re too busy thinking about indicate, signal, maneuver, that type of stuff.

Brett McKay:

So this idea of pattern recognition, if you’re exposed to it long enough and frequently enough, you can start seeing things or noticing things that other people wouldn’t notice. So going back to those indigenous cultures, I’ve read about and I think you’ve talked about them as well, Inuit, for example, that live in the north of Canada. They can navigate these basically ice deserts; everything’s white, everything pretty much kind of looks the same. But because they are so familiar with that environment, they can like recognize like different types of snow, and say this type of snow means this, and so I’m going to keep going that way. And they can do that because they were exposed to it. But if I were to be dropped off in the great white north of Canada, I would get lost probably because I couldn’t make those distinctions.

Tristan Gooley:

Yes, and those patterns are global; so exactly the same techniques being used on the snow by the Inuit can be used by Pacific Island navigators on the ocean. And there are documented examples of captains of ships, of modern ships, perhaps a sailing vessel, being asleep; they’re off watch, they’re down below decks. And they’ll just suddenly come up on deck and say something’s not right. And what’s happened there is their body and their senses have become tuned to the point of sail, the direction the boat is taking over the water. And exactly the same thing happens with sleds over ice and that sort of thing, where a certain rhythm develops. And if you change direction, the sound, the feel, absolutely everything changes.

It might not be … it’s only dramatic if we make it dramatic. So a lot of developing this sense has to do with what we care about, and our brain has evolved to attach more value. That’s what we mean by care. So if, for example, you’ve had problems with burglars in your neighborhood, you’re going to attach a lot more weight and importance to strange sounds outside your home. It’s exactly the same process to any of these things. If the sound of the snow underneath you means you’ve changed direction, and the last two or three times that happened you got lost and spent 24 hours trying to find your way home, we’re automatically going to start to care more about those sorts of sounds and rhythms.

The actually noticing them is very, very easy. It’s just a case of deciding to do that attaching of importance to it and then our brain will do the rest because we have evolved for our brain to take shortcuts. It’s part of our survival tool kit. None of us and none of our ancestors would have survived … Well, I should say none of us would exist because our ancestors wouldn’t have survived if they had to go through a very slow, methodical approach every time. If they had to sort of sit there, and sort of scratch their head and go, “Well, the kind of feel of this snow and ice, or the feel of this water, or even the feel of these sand dunes has changed a little bit. Now let me try and remember what does that mean.” In evolutionary terms, that’s a bit of a non-starter because there’ll be another species that gets there a bit quicker, and that’s really what we mean by survival in a broader evolutionary sense.

Brett McKay:

So all of us, every human being has this ability to look at a tree for example, and see direction, but we have to re-learn it. How long does it take? What does it require to re-learn this skill? Like, do you have to be in the wilderness for extended periods of time? Or is it something you just sort of gradually pick up as you walk around your suburban neighborhood?

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, absolutely. I mean I’m most motivated as a researcher and then a writer by patterns that are as global as possible, as accessible as possible, and with quick meaning. So there are plenty of these sorts of signs that I come across that are just too rare, and they’re of less interest to me and they don’t tend to make it into the book. So what I really like is where a sign can be used in this way to give us a far sense, an intuitive reading of our surroundings, I promote it. I call it a key. So a sign will give us meaning, but we might have to think about it a little bit, whereas a key is something that if we do practice looking at it. So in the examples we’ve talking about, the key there is something I nicknamed the ramp. So what we find is that the wind shapes ice, sand dunes, water waves, even rocks to have two distinct angles; a shallow gradient on the windward side and a steeper gradient on the downwind side.

Now that can apply to a sand dune that might be 200 meter high, but it might apply to a ripple of ice that is only half an inch high. Exactly the same physics is taking place. It can apply to grass. So instead of thinking we have to go and join the Inuit or we have to go out to the Pacific, we can actually see a very, very similar pattern in grass that’s exposed to the wind. There’s a shallow gradient on the side the winds come from, a slightly steeper gradient on the downwind side. And we just practice looking at that, and this is where the caring comes in because if you just sort of look at it and go ‘ah, whatever,’ your brain’s not going to invest the energy needed for the shortcut. But if you actually spend even quarter of an hour walking using just the shape of grass, your brain does a … I’m sort of giving a little bit more of a sort of character here, but it sort of affects, “Oh, so you’re serious about this. Oh, okay. Well if you’re serious about this, then this actually means something to you. Then yeah, sure, we’ll make this happen for you.

And that’s what we tend to find, is that … I find it on expeditions, the sun is the very first example. The sun is due south in the middle of the day, but on a longer expedition I might be aware that it is passing through southeast at a particular moment and I can do calculations that are sort of saying, “Okay, we’re before the September equinox, therefore it’s going to rise seven degrees north of east,” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, all very … in psychology terms, all very slow thinking.

But by the end of the first day and certainly into the second day of an expedition, my brain’s sort of saying to me, “Please don’t do any more of that slow, laborious thinking. It’s really grinding me down. Here, I’ll just give you the answer.” That’s what it feels like. I mean psychologists would probably have slightly better terminology than I’m giving you there, but that’s what it actually feels like. You can just sort of go, you can look at a landscape and you can go it’s this way. And similar to what how we were saying sort of earlier, if somebody says how do you know that, you’d have to sort of take a step back and go well, I kind of know what my brain’s doing but I wasn’t witness to every, single calculation that it did there.

Brett McKay:

You talk about in the book hunters; people who hunt have probably experienced this. I know I have the few times I’ve gone hunting. When I first went out there, I really didn’t know what was going on, but then I had a guide who started showing me things. Like okay, look at the tree; you can see the rut marks. Look at the grass; you can see this is where they’re bedding down. And after a while, after like I think two days, I just started seeing the things, and I knew what it meant, I didn’t have to think about it anymore, and it happened pretty fast.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, that’s a great example. Historically, hunting and obviously for some communities to this day, hunting is the difference between life and death. Therefore, the care is there. And if you are trying to effectively out-compete an animal, even if you’ve got the help of a weapon of some sort, if you notice that certain ear movements precede flight behavior, like deer heading off at speed, that is the difference between success or failure, kill or not, success or not, and survival or not. And in The Nature Instinct, what I try and do is break down every, single one of these behaviors.

So from the face to the tail, and then looking at … it’s basically body language broken down into the typical behavior responses. So to give you an example, if we know that prey animals are going to lift their heads when they sense something in their environment that they’re not entirely comfortable with, we can tell when they sense us. So, that’s the sort of thing I think most people would probably pick up intuitively without having to do an awful lot of thinking about it. But if we then give a little bit more attention to head-tail behavior, we find in certain species like squirrels their next move is quite often predicted by tail flicking. That is a sign that kind of signals that ‘I’m aware of something out there and I may be about to go into flight behavior.’

So that’s one very simple key, but so much of this sort of reading of the environment is about bolting two quite simple keys together to come up with something, which to the novice seems quite advanced, but it isn’t really. So in the case of a squirrel, if we put the peak, as I call this kind of awareness behavior, the key is, my name for it is the peak. The head is lifted. We know if we take one step towards that squirrel, the next likely thing is going to be flight behavior. And with each animal, we can just look at that key; okay, the flight key; where is it going to go? In the case of a squirrel, it’s going to head to a tree. We all know that. But not any tree. It’s probably going to head to a tree that has a network, so it might dart past three isolated trees and then go up the tree that has branches that interconnect with other trees.

So you can now see there were two … well, a lot of this stuff is common sense with hindsight, but it’s, again, hidden in plain sight. So if we tap a friend of the shoulder and say, “You see that squirrel there? When we take two steps towards it, it’s going to get up onto its haunches, it’s going to set up, but it’s going to take two more steps. It’s going to run past those three trees. It’s going to go up that tree there. We’re going to add another key here. It’s going to go into its refuge behavior, which around the back of the tree.” We start to put these things together, and that’s I think at the point where people go, “Wait a minute, this is weird. This is kind of … this is like a sixth sense or something.” It’s not. It’s simple keys put together.

In the case of some of the deer I see near me, very similar behaviors; we just kind of tweak our knowledge of the key for that species. Fallow deer are going to go uphill towards trees. Now if you predict to somebody, “We’re going to walk towards that deer. It’s going to lift its head, then it’s going to run in that direction towards those trees.” Simple pieces, simple keys put together, but they lead to something which we’ve lost but is very retrievable.

Brett McKay:

We’re listening to this, people like, “Okay, you can develop the ability to look at a tree or look at an animal, predict its behavior instantly. Like, all right, so what?” What do you think the benefit is for people to re-learn this nature instinct?

Tristan Gooley:

Well, it’s not entirely practical. I never, with any of my work I never start from the sort of point of view that life will stop if you don’t learn this stuff. So my view is always about experience, connection, and the feeling of engagement, and the again quite hard to describe positive feelings that come from that.

There’s a big movement all over the west world at the moment towards mindfulness, but actually quite often when you pin people down and say what do you actually mean by mindfulness? And if we add to that, people go time in nature is good for us; lots of studies are saying time in nature helps our mental and our physical health. But for me, and I think a lot of people out there, if somebody sort of taps me on the shoulder and says you should spend time and nature and you should be more mindful, I hope I’m polite enough not to say what I’m thinking. But my initial thoughts to people saying that, that’s a lovely, nebulous concept. It’s largely meaningless. But if we tickle our brain by giving ourselves something to look for, which when we practice looking for it, it then leads to this intuitive sense, and with that quite a positive feeling.

I sometimes liken it to feeling like your brain has been tickled. Do you know that feeling when you’re either reading a detective novel or you’re watching a murder mystery type thing on TV or in a film, and you solve the mystery; so you’ve seen the clue. Ah, it’s that.

Brett McKay:

I love that feeling.

Tristan Gooley:

And that, that is the positive feeling. That feeling comes, and in fact that whole genre of murder mystery, puzzles like crossword, Sudoku, any puzzle you name, all of that I firmly believe comes because our brain has evolved to get pleasure from solving puzzles, and originally that was to reward us for understanding what was going on around us. So instead of finishing a crossword and thinking I feel good, I feel clever about that, we can use similar parts of our brain to actually go I think it’s about to rain because the birds are making that sound again. And we get a very similar, we’ve solved a similar puzzle. We’re just using our brains for what they originally evolved to do, and my take is that they doubly reward us for it because our brain’s sort of saying, “Finally, you’ve worked out what I’m for.”

Brett McKay:

In my experience, one of the things that learning how to read nature like this on an intuitive level, it’s empowering. I think oftentimes for people in the Western world, there’s a disconnect from them and the environment, and so there’s this idea that the environment or the wilderness is scary, random, et cetera. And there are parts of it that are just sort of random, right? But as you highlight in the book, there is a, there’s like a system going on that if you know where to look, you can see the gears working in the background. And once you see those gears moving, it feels good; it feels good to know that information.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, I think that’s a good point because I think in a lot of areas of knowledge, people feel that there are experts, and there’s this kind of cabalistic knowledge, and I’m excluded, that group over there, good luck to them, they know it, I don’t, and there’s this kind of invisible wall between us. But there are different reasons for that feeling, but one of the big ones is actually language. I feel very strongly that people shouldn’t be put off any engagement with nature because of vocabulary.

And what so often happens, and we’ve all probably had this experience, is you go out with somebody and they start spouting off names, “Oh, that’s that thing. And that bird, is it this species or that species?” And when people talk like that, if that’s not your lingo there’s an instant feeling of exclusion. Whereas the thing I often to say to people I feel really strongly about is that there is no right name for anything. So for this sort of engagement and to develop these sorts of skills, language is right at the end of what’s necessary, and you can do the whole lot without any names at all.

So we notice colors, we notice shades, we notice shapes, we notice patterns basically. Those are important, and they are to me a global language. So in a tribal, historical sense, you could notice the body language of a bird and know that it’s about to take off, and then you could debate for another three weeks what the right name for that bird is. It doesn’t change the body language or the fact that you’ve sensed that it’s about to take off.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, and I think one thing that you talked about, too, is that there’s this … I guess conservationists, one of the sort of metrics they use to determine whether someone’s in tune with their environment is the number of species, plant species they can list in their local area. That’s actually, like you said earlier, that’s not a useful metric because you might know the names, but then that’s as far as your knowledge goes of that fauna or animal.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, absolutely. And I think we can, if we look at young children, they don’t take to names terribly quickly, but they learn things like stinger nettles, and around where I am things like brambles, things like that; anything that causes pain is a lesson that we learn a lot more quickly than names. There could be a hundred common names for a wildflower, and I get into these conversations where people say, “Ah, but that’s why we use the Latin.” And I always say, or sort of saying something along the lines of, “The Latin’s not so strong in the heart of Borneo, and they know their plants really well.” So there is no right name, but there is recognition of patterns and that is a different sort of language.

Brett McKay:

Another benefit that I think comes from re-learning this nature instinct that I got from your book, but also just my experience learning how to do this stuff, is that it gives life more meaning. There’s that sort of … people write about ‘there’s a crisis of meaning in modern life,’ but I think the nature instinct is one small way where you can inject more meaning into your life. You can look at the world and say that means something, and I don’t know, there’s something fulfilling about that.

Tristan Gooley:

Thank, yeah. And that’s certainly one of the things I hoped to achieve with this book, and for me the tipping point personally, which is now something I try and share because I think it is, it can be the difference for people deciding whether to give this a go or not, is very early on in my life; I mean, I sort of got the point where I go, “I hope it’s not a cloudy day because then I can see the sun and I can use the sun to find direction,” or “I hope I can see the stars.” But the time I was in my early 20s, the collection of signs was probably big enough that I was hopeful of finding one out there.

But there came a point where my whole philosophy changed, which is now everything outdoors is a sign; literally everything has some meaning because nothing is random. And that stretches all the way from the wildest parts of planet Earth, where we might be noticing that a sudden spike in the number of insects is telling us that there’s water nearby, all the way up to urban examples. You know, shops are not random. Somebody spent a lot of money to put a store somewhere, so although I’m focusing on nature, the philosophy applies to literally everything. The color of the side of a building is trying to tell us something about the amount of light and moisture, which in turn is telling us direction. The way people move is analogous to the way animals move. It’s not random.

Any one individual might decide to go somewhere strange on any particular day, but a group of people moving along a street late in the day heading towards the station, that sort of thing is not a random pattern. So feel free to fire it back at me, but I’ve yet to have an example given to me where I’m left thinking there is no sign in that. Sometimes it takes me awhile to work out what it might be, and sometimes the sign isn’t super powerful. But there is, I believe, a sign in everything. And once people sort of become open to that sort of idea, then every minute outdoors becomes very, very exciting because instead of it being a thought, “If I’m really lucky I might find one of these things that Tristan was calling a sign,” it quickly becomes, “Everything’s a sign.” So if I look at something, the thought is what is it? And then you’ve got your kind of murder mystery feeling.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, and it causes you to engage with the world in a more active way, and I really like that feeling. Another kind of high level concept that you talk about in The Nature Instinct that I thought was interesting was this idea, and I’ve never heard of this before, but it was the idea of the umvelt, or umwelt … did I pronounce that? I think it’s German; or umwelt. What is that and what insights can it give us to developing the nature instinct?

Tristan Gooley:

It was one of the great joys of this book for me because it had to be pointed out to me that the word author is connected to the word authority. I wasn’t a genius when it came to that little quite simple connection. But nobody gets commissioned to write a book unless they’ve proved that they are expert enough in that field that the world will have an interest in what they have to say about it, which is again sort of slightly obvious stuff. But the great joy in writing any book is you enter it with a level of knowledge which is high enough to justify the exercise from a publisher’s point of view and a reader’s point of view, but you always learn little things along the way and that is so, so exciting from my perspective.

And this … I don’t know the exact way to pronounce it; I’m guessing as it’s German, I think it’s umvelt, but my German is close to non-existent, so forgive me anyone if I’ve got that wrong. But I’ve only ever seen it in print, but I’m very familiar with the concept now, which is that this is the landscape and the environment as perceived by another creature, which initially doesn’t sound that exciting. But when scientists start looking into this, some really quite bizarre stuff starts to happen because quite often we can see creatures that have much, much smaller bodies and brains than us doing things that look a bit smarter or certainly a bit more able than us.

The most beautiful example is one I cite in the book, which is the Jackdoor going for a locust. So the bird sees the locust, and the locust is moving in front of the bird, and the bird identifies a male. But the locust has evolved to notice the predator there, notice that moving is not the right thing to do, so the locust freezes, which is another of the keys. And what is interesting is at this point, the bird ceases to be able to see the locust. The meal has become invisible not in a sort of ‘it’s no longer grabbing my attention.’ As in as far as scientists can tell, that actual, that there is no vision there anymore. It’s almost like somebody’s turned off the lights, and this is why we see freezing so much in nature and why we instinctively quite often do it.

If we’re walking through a woods hopeful of seeing some wildlife and we catch something moving around us, it’s quite, it is quite a sort of intuitive and instinctive response to freeze. But the more time you think about it, the more you realize that it’s not that animals sense the world like us; they just don’t have language like English attached to it. It’s they are sensing an entirely different world, and that’s where when I’m spending time … if we come back to squirrels, if you wave your hand and imitate the motion of a squirrel’s tail, it feels hilarious because you feel like a bit of an idiot.

My family and I were over in New York recently and we’re in Central Park, and I was having a conversation and with a squirrel there by waving my hand. And beneath the sort of ridiculousness of how it looks, there is something genuine going on there because the squirrels, I can’t tell exactly what’s going on in their brain, but they definitely, they are definitely picking up the sign, and hardwired into them that motion has a meaning. Now my take is that that meaning doesn’t quite fit with the rest of what they’re seeing, as in they’re not thinking wow, that’s a big squirrel. They’re thinking I’m getting a sign with meaning and that is an instant, fast understanding of what’s going on somewhere. But they’re then probably getting the subsequent hang on a minute-type feeling as well because the other signs and patterns aren’t fitting it. So through that, the little insights again to how different creatures are experiencing their environment allows us to have more faith and believe a little bit more that these signs do actually work that way.

I mean another example is prey animals like rodents have to be very, very sensitive to birds overhead, because birds of prey can sweep down and it’s game over. So they are tuned to the shape of birds. They don’t related to birds in the same way that bird lovers around the world might do. They might buy a guide book and they might say, “It’s got bars on its tail feathers and the ring around its eye is this color.” That’s a very, very slow, human way of looking at a bird.

A prey animal will just sense the shape, and if that shape is of a bird with a short neck, it’s gone instantly. It’s not, as far as science can tell it is not the rabbit or the rodent or whatever it is, it’s not sitting there thinking, “Look a little bit like predator A, which can kill me, but not at all like predator B, which is safe. Okay, if it looks like the one that can kill me, I’m going to head off.” All it does is sense a shape, and that is its umvelt. That is its whole reading of the sky. As far as we know and my best guess is it’s not even sensing a bird. It’s sensing a shape which means run for cover.

Brett McKay:

All right. So we’ve been talking about this stuff on a high level. We talked about the benefits of developing this nature instinct. I think there’s a big case for it, not in a practical sense. I think a lot of people think I’m going to learn this stuff so if I ever get lost in the woods, yeah, it’ll probably come in handy. But I think most on a day to day, it just gives more meaning, enriches your life. But to develop that nature instinct, we have to learn these things deliberately first, and then with practice they become encoded, so it just becomes like instinct.

So let’s talk about some of these patterns. We’ve mentioned a few throughout. We talked about the ramp that we see in nature in different places that indicate wind direction. What are some of your other favorite signs in nature that, once people know that they’re there and notice that they’re there, they start seeing them everywhere and it tells them information about their world?

Tristan Gooley:

One of my favorites is a good one for people to learn early on because it stacks the odds in your favor. If you’ve ever had that experience of going outdoors into a rural or semi-wild environment and thinking, ah, this is going to be a feast for the senses; I’m going to see a lot of wildlife and a lot of nature happening in there. And then after 20 minutes, you get that feeling there doesn’t seem to be a lot going on here. Well that’s, it’s partly because we’re there and we haven’t necessarily settled into the landscape, so there’s a lot of creatures out there watching us to see our next move. But there are things we can do to massively stack the odds in our favor.

The keys I call, the edge is a nice, simple one. So in ecology terms, it’s known as an eco-tone, where two landscape types meet each other, we get a massive spike in activity. And when I first sort of was getting familiar with this sort of concept, I thought I’ve noticed that happening but I don’t really understand why. I mean, what’s the logic? And a lot of it’s very simple math. So if you’ve got woodland meeting a field, open country, for the sake of argument you might have 50 species that need woodland to live in, and 50 species that need an open field to live in, and there might be 50 species that need both. There is only one part of the landscape where you’re conceivably going to see 150 species.

Now if we imagine those are 150 prey species, we’re going to see a spike in predator activity. And indeed, what we tend to find is these edges are sort of mini-highways. We’ve got the prey moving up and down them; we’ve got the predators focusing on that as well. So instead of us scanning, if we had … in gambling terms, if we absolutely have to see something happen and we’ve only got five minutes in our landscape, there’s no point scanning the whole landscape. The animals aren’t doing it, and they’re the ones that really know. You focus on the edge.

And then we add another key, which comes from an old Medieval English hunting term, which is the little sort of, the mini-highways through undergrowth. So if we image we’ve got a wood touching a field, there will be some undergrowth there; perhaps some thorns, some brambles, some things like this, there will be lots of animals that can’t pass freely through that. So anything bigger than a small rodent is not going to be moving randomly through that. So we find these, sometimes they’re tunnels, but they always exist. So it’s not like you have to go and search for half an hour; you’ll be able to see one within a couple of minutes quite easily. So then we’ve got the edge, where most of the activity is happening, and this little kind of highway, which is it’s a funnel, it’s a pinch point, it’s where stuff is going to happen.

The final key we add is time, so we will, again the max is really quite clear here. We’re going to see a lot less in the middle of the day and the middle of the night than we are at dawn and dusk. The reason for that is that in evolutionary terms, prey has its best chance of in sense terms outwitting predators when it’s half-light because the nocturnal animals can’t use their incredible night vision. Animals like owls in twilight are at no greater advantage, whereas the middle of the night, of course they’ve got their trump card. In the middle of the day, a lot of prey animals are extremely vulnerable to being that well lit. So if we had the time, in the book I give it this sort of funny nickname, which is just a Greek name for a water clock, because I’m just trying to get people to think about time differently. And there what I’m encouraging people to do is think about the edge; think about the, the little highway through it; and then think about not clock time, but for example, sunset time, and then relate that to weather.

So if we put all the pieces together that we find, it’s been very dry for five days. It’s been a little bit of rain. We normally see activity round about 20 minutes past sunset, but because it’s been dry and it’s been a little bit of water, we got used to the idea that brings our nature clock forward a bit so we’re actually going to head out at sunset. And suddenly you see sort of four animals out there, whereas if you’d had an hour just looking at the whole landscape at the wrong time, you’d see nothing.

Brett McKay:

I think one nature instinct that people would like to develop is the ability to predict weather. Maybe they’re great-grandfather or grandfather was like, “I feel like it’s going to rain today.” Like they could feel it in their bones. Is that really a thing? Are there like signs that you could look for in your environment that can help you figure out if it’s going to rain or if it’s going to be snowy, if it’s going to be foggy? Have you found any tried and true signs?

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, definitely. And I’ve been doing a lot of research in this area and there are examples in all my books about the weather. And it is quite a good example of the big, quite dramatic signs all the way down to really very subtle stuff that takes focus and experience.

The biggest one is like so many nature signs, is related to wind. If we just make a habit of noticing where the winds come from in very, very crude terms; we don’t even have to sort of … we’re not sort of getting to the point of sort of saying it’s south-southwest or anything like that. It can just be I’ve noticed it comes from between those two buildings, or it comes over that mast on a hill, or something like that. You’re just, okay, that’s where it’s coming from now. And then a few hours later, you go wait a minute, it’s changed. That is the sort of thing that our ancestors … that’s just in neon lights in terms of indigenous and I believe ancient reading of landscapes. It’s just for the simple reason that if a constant wind shifts direction by more than 20 or 30 degrees, something’s on its way because again, nothing is random. So, that is a very strong indication that a frontal system may be about to go through.

Then we move to quite bold cloud signs. So what I encourage everybody to do is cheat early on. Wait until you’ve had a really good, one of those quite sort of well-established good weather times. It doesn’t have to be summer at all, but where you have sort of four days of blue skies, light winds, you start to get that feeling that this is going to last forever. We know it doesn’t. And then cheat. When you’re early on, this is about getting from slow to fast thinking, what we do is we way, okay, right, I’m going to cheat. I look at the forecast. Oh, okay, so I can see that there’s a front coming through and it’s due to start raining in 24 hours. I’m just going to scour the sky once every hour over the intervening time.

And you start to notice wispy, sort of candy floss cirrus clouds, and then there’s kind of almost like, sort of think frosting, cirrus stratus cloud comes, that’s the one that gives us halos and things like this. And like so many of these things to start with, we’re having to kind of sell the concept to ourselves. We’re having to convince ourselves that this stuff works. Okay, well I’m feeling a slight pick up in the wind; I’ve noticed that it’s back and it’s moved anti-clockwise; it’s no longer over that tower, it’s now coming from over that wood. And wait a minute, it was completely blue three hours ago, and I’m now seeing little bits of, you guys call it something else, we call it candy floss. Oh, I forgot what it’s called over there. What is the name?

Brett McKay:

Oh, cotton candy.

Tristan Gooley:

Cotton candy, yeah. And then we do that a few times cheating, and then we do start to go, okay, this stuff works. And then the next thing that happens is that we move from knowing what’s going to happen with a bit of help from modern forecasting to actually just sort of going, oh, the weather’s about to change. And then when it does, we get that huge solve the mystery type feeling. And so that’s pretty much, I wouldn’t say it’s with us automatically forever then, but like so many of these things, you’ve got to push it up the hill a little bit and then it just rolls down the other side and you have a lot of fun with it.

Brett McKay:

And some of my other favorite signs were animals, and looking at their behavior to help you figure out about your environment. So this idea that I think cows, they typically stand north-south; typically, it’s not always, but oftentimes. So, that’s one way you can look at animals to find direction. The other one is like using animals to find water if you’re out in nature. You can look at how animals behaving and see, oh, there’s probably water in that direction.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, there are two ways of coming at this. There’s the kind of very broad map making sense, which is all plants and animals have a relationship with water, we know that. But if we kind of finesse that a little bit and think, okay, every animal will be found within a certain radius from water. And this applies to every animal and every landscape type. So if we think for example, if we turn it on its head, the Pacific Island navigators know how to find land by using birds which will only fly a certain distance from land. So there are certain birds like the Frigate, for example, that will be found 70 miles from land, and others like the Boobys that will be found 40 miles from land, down to the Terns at 20 miles from land; if we come back and flip that back on a land sense, the land becomes like the ocean and the water becomes like the island, as in certain animals will only be found a certain distance.

So within birds, what we find is that the corvid family get a lot of their moisture from the animals they feed off, so they can be found a very long distance from water. But seed feeding birds and other birds, woodland birds like Pheasants, things like that, they indicate water really quite close by because they won’t range far from it. But the general principle is more important than the detail here because the details can change all over the world, but the patterns and the principle doesn’t, which is every, single animal you see is telling you something about the proximity of water. So that’s kind of one very general principle that works all over the world and has saved peoples’ lives on countless occasions.

The next is to look at individual behaviors and see if you can refine that map; so see if you can go from thinking, okay, there’s definitely water within half a mile of here, to thinking okay, where is it. And there we can start to look at things like flight patterns. So a lot of birds will fly to water in the morning or at the end of the day, and I won’t claim that I can do this routinely although I do keep trying, but there are documented cases people like the Aboriginals in Australia being able to tell whether a bird is coming from water or to water by the way it alights on trees. So if we kind of think of birds, even big birds don’t weigh much, it doesn’t take much water to weigh them down, so a bird that’s coming from water will effectively hop from trees because it’s lugging a great big tank of water with it. Whereas a thirsty bird that hasn’t had any in the morning will take a direct flight path straight past all the trees in the direction of the water hole or whatever it’s resting on.

Brett McKay:

So yeah, there’s a lot of signs and as you said, the key, what you’re hoping people will do is they’ll deliberately learn these things by reading it in your book, but then get out there and practice it so they get to the point where they could just see something and they know what that means without having to think about it.

Tristan Gooley:

Yeah, and I, all my books, I try and give people a real wealth, a large number. I mean, there are 52 keys in The Nature Instinct, but realistically I think of them slightly like characters in the sense that I can’t predict who’s going to get on with which one. If we kind of imagine we’re going to a big house party and there are 52 people in it, the chances are you’d get on really, really well with a handful of them, and a few of them are going to leave you cold. It’s the same with these sorts of signs, and each of us has our interests from our experience and our preferences, so all I’m really doing is hopefully a good introduction to 52 of these keys.

And then it’s down to the individual to sort of say that, that really resonates for me. That’s what I like. I am really into birds, therefore I’m going to look for this particular key, and then a relationship forms. It makes me sound incredibly dysfunctional talking about sort of signs in nature as sort of characters, and I don’t always manage to shop short describing them as friends because it does feel like that. There are certain ones that it doesn’t take long before you recognize them, and you kind of feel a kinship; it’s kind of yes, there you are because it’s such a positive feeling. That all sounds weird until you actually get out there and try it, and then you’ll know exactly what I mean.

Brett McKay:

It’s always weird until you do it, and then it’s not weird anymore. Well Tristan, where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Tristan Gooley:

Thanks. I have a website, naturalnavigator.com, and I’ve been adding examples to that for over a decade now, so there are hundreds in there. There’s information about my books. I’ve written a few now, and again, I’m coming at the same idea from different angles. I’m on a lot of the sort of usual social media things; Twitter, Instagram, Facebook. But yeah, I just encourage people to pick one or two, keep having a bit of fun with them, and then instead of it feeling like you’re having to put stuff in, you just start getting, giving stuff back and that’s a really lovely moment.

Brett McKay:

Well, Tristan Gooley, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Tristan Gooley:

Thanks so much, Brett. I’ve really enjoyed our chat. Thank you.

Brett McKay:

My guest today was Tristan Gooley. He is the author of the book, The Nature Instinct. It’s available at amazon.com and book stores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at his website, naturalnavigator.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/nature instinct, where you can find resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the A-O-M podcast. Check out our website, artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives, those thousands of articles we’ve written over the years about physical fitness, how to be a better husband, a better father. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the A-O-M podcast, you can do so in Stitcher Premium. Head over to Stitcher Premium, sign up, use code manliness for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the A-O-M podcast. And if you haven’t noticed already, I’d appreciate it if you could take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to not only listen to the A-O-M podcast, but put what you heard into action.