In the first post in this series we discussed the concept of the “Pyramid of Choice,” and the way in which taking an initial dishonest step can potentially set a person on a path of increasingly serious misdeeds that eventually carries them far away from their original principles.

Yet one or even several bad choices do not cause most of us to slide all the way down into the gutter of utter corruption and depravity. Instead, we often make a few bad choices and then decide to right the ship and get back on track again.

What checks our behavior and prompts us to stop the slide? What determines how far we journey down the path of dishonesty before we decide to turn around?

Part of it is our desire to strike the balance we have talked about previously between wanting to benefit from a dishonest act and wanting to still be able to see ourselves as good people. Committing too many misdeeds can begin to compromise our positive self-image and prick our conscience, prompting us to beat a trail back to a place where we don’t feel like such a shyster.

Yet people seem to reach this tipping point at varying distances along the path of dishonesty, and you have probably let yourself slide for longer or shorter durations during different times in your life. So we are still left with the question of what may account for these variations.

The answer, at least partially, is moral reminders – checkpoints that help you remember your standards. The number and regularity of the moral reminders in your life can greatly determine whether you rarely step off the path of integrity, and quickly get back on track when you do, or you find yourself at the bottom of the pit of immorality, unsure of how you ever fell so far.

The Power of Moral Reminders

For his research on the nature of integrity, psychology professor Dan Ariely didn’t just want to find out what made people more likely to cheat, but also what worked to keep people honest.

To discover what might be an effective integrity booster, he returned once again to his tried and true matrix test and the condition that allowed for cheating. This time he divided the participants into two groups. Before they started the test, he had one group think of ten books they had read in high school and the other group think about the ten commandments. When the results were tallied after the test, the first group had demonstrated “the same typical but widespread cheating” that had been found in previous conditions of the experiment. But for the group that recalled the ten commandments before beginning their matrices, the rate of cheating was 0%. This, Ariely notes, “was despite the fact that no one in the group was able to recall all ten.” A simple reminder about morality right before being faced with the opportunity to cheat had effectively thwarted the temptation.

What’s interesting is that when Ariely conducted another experiment, this time having a group of self-declared atheists swear on a Bible before beginning the matrix test, they didn’t cheat at all either. Ariely concluded that moral reminders are effective even if the specific “moral codes aren’t a part of your personal belief system.”

He found similar results when he tested the effectiveness of moral reminders in a different way. This time he had students from MIT and Yale sign a statement before taking the matrix test that said: “I understand that this experiment falls under the guidelines of the MIT/Yale honor code.” The act of signing the statement also resulted in zero cheating, and this was true even though neither university actually has an honor code. What mattered was that the student had to undergo a small ritual that got their brain thinking about morality right before that moral sense was challenged.

As Ariely concluded from this line of his research, “recalling moral standards at the time of temptation can work wonders to decrease dishonest behavior and potentially prevent it altogether.”

Virtue Forgetfulness and the Needed Regularity of Moral Reminders

The problem with human nature is that we are all prone to what might be called “virtue forgetfulness.” Our principles and values – our vision of the men we want to be — do not stay at the forefront of our minds at all times, ever at the ready to sway our choices. Instead, our craniums are so busy processing our day-to-day issues and concerns that more philosophical data ends up stored in the reserve trenches rather than the frontlines. It is for this reason that moral reminders are so effective and necessary in our lives: they act as cues in our environment that summon thoughts about our values from the back of our minds to the front, where they can influence our behavior and be brought to bear on the temptations before us.

(For an in-depth explanation of both the philosophy and science behind this phenomenon, I highly recommend reading this post: Hold Fast: How Forgetfulness Torpedos Your Journey to Becoming the Man You Want to Be, and Remembrance Is the Antidote.)

It’s not enough to receive a moral reminder every now and again; regularity is key. Ariely saw this truth played out when he had students from Princeton participate in his matrix test. Unlike MIT and Yale, Princeton does have its own honor code. Freshman must sign it when they enroll, and they attend lectures and discussions about the code when they first arrive on campus. Wanting to find out if such ethics training would have a long-term effect on their behavior, Ariely had a group of Princeton students participate in a matrix test two weeks after completing their honor code orientation. But the students still cheated at the average rate. It was only when they were asked to sign the same pre-test honor pledge that the MIT and Yale students had, that their cheating also dropped to zero.

Thus we see that becoming a man of integrity is not like riding a bicycle; you don’t learn how to do it once, and then expect to ride that ethical conviction as an automatic behavior for the rest of your life. Instead, acting with integrity is something you have to decide to do over and over again, and the more moral reminders you have in your life that reinforce your commitment, and the more regularly you encounter those reminders, the easier it is to stay on track.

How to Establish Moral Reminders in Your Life

I think the fact that virtue forgetfulness is a universal trait is reflected in the fact that all the world’s religions, despite greatly varying doctrines, employ moral reminders to keep people on the straight and narrow. Prescriptions to pray multiple times a day and regularly study one’s scriptures are really calls to partake in regular moral reminders that ritually reinforce one’s faith and its code of behavior.

For believers of some religions, these moral reminders can be quite concrete and intimate, as Ariely demonstrates in retelling “a story in the Talmud about a religious man who becomes desperate for sex and goes to a prostitute”:

“His religion wouldn’t condone this, of course, but at the time he feels that he has more pressing needs. Once alone with the prostitute, he begins to undress. As he takes off his shirt, he sees his tzitzit, an undergarment with four pieces of knotted fringe. Seeing the tzitzit reminds him of the mitzvoth (religious obligations) and he quickly turns around and leaves the room without violating his religious standards.”

Moral reminders aren’t just for theists, however. Atheists will argue that they can be just as moral as any religious person, and I for one don’t disagree with that. Yet an atheist’s morality must be guarded, cultivated, and strengthened like anyone else’s.

There are plenty of ways to create secular moral reminders that can be effective for the integrity-seeking atheist, as well as serve as additional supplements for theists who already partake in traditional religious reinforcers like prayer, scripture study, and weekly worship. The simplest thing to do is to try to consciously recall your moral standards before you’re faced with a temptation, as the students who thought about the ten commandments did before the matrix test. But of course in real life we often don’t know when a temptation is coming, and in the heat of the moment, we may be incapable or unwilling to summon our principles to the forefront of our minds. For this reason, you should cultivate built-in moral reminders that you can encounter each day without much effort.

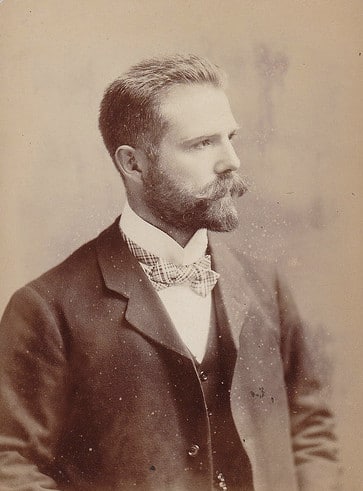

“Truth is much more forcibly impressed upon the mind when accompanied by illustration, either in incident, anecdote, example or in a drawing or picture. Where the mere statement of truth in the abstract may fail of results, the illustration comes to the aid of truth and impresses and fixes the thought upon the mind.” –Henry F. Kletzing, Traits of Character, 1899

First, I recommend hanging up wall art — especially by the door through which you leave for school or work — that reminds you of your standards and the man you want to be each day. Here are some examples we have hanging up in our home:

Clockwise from top: 1) Benjamin Franklin’s daily affirmation, 2) an illustration from a 19th century book on character, 3) a modern play on a popular WWII song that reminds me to live up to my grandfather’s values.

Second, consider creating a personal manifesto and reading it each and every day, as AoM reader Zach Sumner did. You might also shrink it down into a laminated card you can carry in your wallet or pocket notebook and review regularly.

Another idea is to wear a piece of jewelry that reminds you of your standards. This could be an item with religious symbolism or a watch your upstanding grandfather gave you. If you wear it every day though, you can start taking it for granted, so make it a point to touch, fiddle with it, and think about its meaning consciously each day.

Even something like a tattoo that you often see can serve as a moral reminder of who you want to be.

There are also some smaller, simple things you can do to try to stay on track. Keep post-it notes on your computer with some kind of phrase or saying that motivates you throughout the day. Use a photo of your spouse/loved one/family as the background on your phone, so that you’re always reminded of the reason you’re trying to be a man of virtue. Take a page out of Ben Franklin’s book and use a pocket notebook to record any indiscretions you may commit – the simple act of writing it down puts it more in the forefront of your brain moving forward. Be creative in this endeavor and find what works for you!

Employing moral reminders is especially important when you’re away from home; Ariely theorizes that we’re more likely to engage in dishonest behavior when we’re on a trip since we’re outside our day-to-day routine, away from the eyes of those who watch us, and the social rules aren’t as clear. For such reasons, while there aren’t any statistics on how often infidelity occurs on business trips and the like, the popular perception of it as a frequent occurrence is probably not too far off the mark. So if you want to stay true while jetting around the world, be sure to pack some moral reminders along with your luggage. Check in with your significant other frequently, put her picture on your nightstand in your hotel room, and don’t take off your wedding ring – doing so isn’t just a literal move to signal your availability, it’s a psychological impulse to rid yourself of a moral reminder that might deter you from following through on your desire to cheat.

Pressing the Reset Button

Moral reminders won’t force you to do the right thing. They’re just checkpoints where hopefully you’ll be prompted to stop and reflect on your values, giving you the strength to resist temptation. But you can also choose to blow right through them.

So what do you do if you’ve never instituted moral reminders for yourself, or have lately chosen to ignore yours, and you find yourself far enough down the road of dishonesty – having maybe even reached the what-the-hell point and really gone on a bender — that you’re unhappy with yourself and want to find your way back to the man you’d like to be?

Just as it’s not surprising that all religions promote moral reminders to their adherents, it’s also not surprising that all faiths offer opportunities for repentance or renewal.

Christians have the weekly Sabbath; Catholics, the sacrament of confession; Jews, Yom Kippur; and Muslims, Ramadan. These rituals allow people a chance to hit the reset button on their lives and begin again with a fresh start.

As with moral reminders, just because you’re not religious doesn’t mean you don’t need such reset rituals just as much as the next fallible human being. There are secular events that can be used as psychological turning points in the same way: birthdays, New Years, moving, break-ups, new jobs, and so on. And you can intentionally create your own regular times of renewal, like bi-annual camping trips where you take time to reflect, sort through mistakes you’ve made, and commit to doing better in the next six months. Create your own rituals like writing about your regrets, tossing them into the campfire, and watching them burn away.

Series Conclusion

We hope you have enjoyed and gotten something out of this series on integrity. Ariely’s research on the subject does not offer all of the answers to the nature of morality, but we felt that it was a fascinating jumping-off point for creating personal reflection and group discussion. I know I have experienced the former myself, and I have not been disappointed in the thoughtful nature of the latter in the comments.

One of the things I found most interesting about Ariely’s research was how closely his results mirrored the sheep/wolves/sheepdog paradigm articulated by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman. As we explored in our series on that subject, Grossman believes a very small percentage of the population are wolves, a very small percentage are sheepdogs, and the great majority of people are sheep.

What Ariely found in conducting his matrix test was that very few people cheated to the fullest extent possible. Likewise, very few people were strictly honest. Most people cheated…just by a little. Ariely reports that while they did lose money to the small number of big cheaters, they lost far more to the many people who were willing to each fudge a bit. Small lies, multiplied by lots of people, added up to a big impact.

While the media often focuses on the big problems of corruption in our time, and politicians debate how best to fix them with broad rules and regulations, the solution to establishing a more honest society may lie far closer to home. If each individual man committed to living a higher standard of integrity, if he strove not to compromise that integrity in even small ways, and set an example that inspired others to do likewise, our homes, neighborhoods, and nation would slowly become better places for all. Our world will never be perfect – either individually or societally – but why not do whatever you can, wherever you are, to make it a better place now and for those coming after us?

Read the Series

Part I: Why Small Choices Count

Part II: Closing the Gap Between Our Actions and Their Consequences

Part III: How to Stop the Spread of Immorality

_________________

Source:

The Honest Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone–Especially Ourselves by Dan Ariely