It often seems that men and women have never before held such a low opinion of the opposite sex. Women complain that there are no more real men out there, that today’s generation of males are akin to a tribe of rude, crude, lost little boys, who won’t commit and are drifting through life. Men lament that modern women are the worst crop of females the world has ever seen — that on a whole they’re flighty, crass, and prickly, and come in two equally unpalatable flavors: angry social justice warrior and entitled princess.

Have women and men really devolved from a past golden age, when ladies were ladies and men were men?

While the Art of Manliness has a nostalgic bent both in our aesthetics and in the way we often draw lessons from history, because we spend so much time researching that history, few know as well as we do what was and was not in fact true about the past. In particular, as a collector of old books, ephemera, and vintage men’s magazines, I’ve gotten a unique look at how men actually used to feel about women back in the day. And the truth of the matter is that there’s never been a time when men haven’t complained about women (and women haven’t complained about men).

Some of the complaints of yore are unique to the time, but many have held surprisingly consistent through the ages. Indeed, though folks often react to the “red pill” sites out there as if they’re some kind of new, unprecedented phenomenon, pretty much everything brought up on those forums, both in content and tone, can be found in the men’s magazines of the 40s, 50s, and 60s.

Don’t believe me? Let’s take a look at just a few excerpts (edited for length) from books and magazines, not only from the mid-century “golden age” of sex relations, but even farther back to the 1800s, and see what men used to complain about women.

What Men Complained About Women 50+ Years Ago

In the September 1946 issue of PIC, a magazine for college-aged men, coeds shared their complaints about their male classmates’ behavior and style. WWII had just ended the year before and most of the men on campus were veterans. The ladies’ answers thus generally revolved around the fact that men weren’t dressing up enough and often came to class in the military clothing they had been issued during the war; for example, guys often hung out in their government-issued t-shirts, which the ladies thought looked like underwear. Men in jeans was another trend they weren’t crazy about. The women also complained that college men drank too much, didn’t give them enough notice before dates, and preferred to hang out with their buddies instead of socializing with the girls.

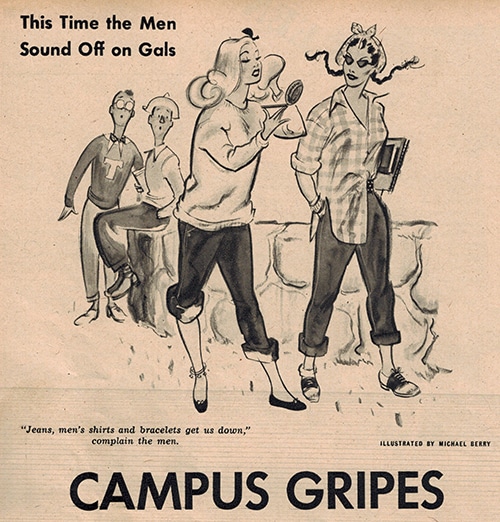

The men got their turn to sound off in PIC’s subsequent issue. Their complaints generally swung between bemoaning the high-maintenance ladies who wore too much make-up, and lamenting the women who had carried over mannish “Rosie the Riveter” fashions from the war.

“Campus Gripes”

From PIC magazine, 1946

When we gave co-eds the green light to sound off on college men’s gear and actions in the September PIC we thought their acrid comments would shrivel the lads into a deafening silence. We were wrong. The boys put up their dukes and started bringing their punches off the floor. In two words, their collective letters add up to something like, “Oh yeah!” O.K. men, we backpedal, throw in the towel, and give you the floor. Take it away.

Quote the Newark College of Rutgers University: “So they like us clean-shaven! Well, even with three-day stubble we don’t look as bad as some of them look with their war paint. When I was in grade school, I was taught that two coats of paint were enough for any wooden article I made in manual training class.”

Says another lad, “A fellow doesn’t stand a chance with a sorority girl after she gets through comparing notes with her sisters after a date.” And still others, “Parlor dates are as extinct as the Vanishing American—these days if you date a girl, you’re broke for two weeks.”

Loud in lament was a group who wished girls would “carry tissues to remove lip rouge before kissing—and it’s no fun trying to get that pancake stuff off our collars.”

Here’s a choice bit of description from a junior at New York University: “These jeans and men’s shirts the girls wear, get me down. They look like a bunch of bombed-out refugees trying to trade for a can of Spam.”

Bergen College is in the ring: “I wish girls would realize most of us are in the 65-12 Club—65 dollars a month for 12 months—GI Bill of Rights stuff. You’d never know it from the way they suggest the Stork Club for a date.” Another lad voices a pet peeve—girls who take up classroom space that could be used to educate more vets: “If it’s just to meet a man that they come to college—tell them to stay home. We’ll find them.”

Under attack from all the lads are: “The distinct line of demarcation where the make-up ends and the skin begins, slacks that accentuate the negative, pancake make-up you have to dig through to kiss a girl, eyebrows tortured into a hair line, ankle bracelets that tinkle like cowbells, eye-blinding nail polish, unwashed and greasy hair, bleached hair that hasn’t settled into one color, blue jeans—especially the rolled-up-on-one-leg kind, and lipstick on the teeth.”

And a senior offers advice to the lovelorn: “A girl who insists on putting up the top of my convertible so her hair won’t get messed in the wind, is a dead duck for another date”

Still another sad sack lists things that bore him to death—“Girls who talk about the other guy, girls who read love stories instead of newspapers, the matriarchal type, and the type that tries to make a brother of you even after the first date.”

Also on the Stanford disapproval list are shoes worn without either socks of stockings, wooden-soled Dutch shoes, girls who’ve bought up men’s white shirts—then wear them in giant sizes to go with tight-fitting blue jeans, pigtails, broad-studded belts, bandanna-and-pork-pie hat combinations for rainy weather, girls who look so good at formals that you can’t recognize them on the quad, and “saddle-shoes that look as if the wearer spent the night prowling around Rossetti’s creek bed.”

And now for the tenderer side of things. “With all their faults, we’ll take American girls to foreign women any day” is the unchallenged opinion of the American college man, who adds “And I ought to know.” Sampling in foreign ports has convinced him that Susie College is the “prettiest, sweetest, wholesomest and smartest girl in the world even if she isn’t the most cooperative.” Most of them will grovel at her feet if only she’ll stay away from the pants. “No pants please!”

The article below actually ran in the same 1946 issue of PIC, and provides a counter to the other piece’s contention that American women are the best in the world. The author laments the fact that the greater independence women gained during the war was not being wholly relinquished.

“I’m Fed Up With Career Girls”

From PIC magazine, 1946

Now let’s not treat this as an indictment of all American womanhood. For surely, there must be some women left in this fair land who still retain those feminine graces Grandma knew in the days of lavender and lace. But there’s an ever-increasing segment of the country’s female population which is all-out to prove it’s a woman’s world—and to hell with the war-worn GI who’d like to seek self-assertion somewhere other than behind a door labeled “Gent’s Room.”

I’m speaking of America’s Smart Young Businesswoman—the Career Girl, to coin a cliché. She’s the gal whose economic independence has given her a chance to forget the word femininity. For when it comes to being feminine, the current crop of the nation’s lovelies are a sorrowful lot. Schooled in the routine nine-to-five as smart young executives, they’ve become a legion of well-tailored mannequins, each with the warmth and personality of a cam shaft. As for any observances of the social graces—that’s a joke, son.

It used to provoke no end of ire on the part of American girls to hear GIs speak favorably of their female friends in Australia, France, or Italy. “What is it they’ve got that we don’t have?” was the angry cry. “Nothing, but they’ve got it here,” became the rejoinder. Unfortunately, that remark is a grave misstatement. For as a former correspondent recently noted, the European woman is head and shoulders above her American counterpart when it comes to exercising a few of the proprieties normally expected of women in public.

Several days ago I met an old friend who expressed considerable doubt as to the strength of his wartime marriage. He had served outside of the country for a full three years and he’s now discovering that this business of readjustment isn’t done by the numbers. His wife, who had never worked before, is holding an excellent job as copywriter for a leading advertisement agency. While he was in Europe she had the foresight to rent an apartment—supposedly a sincere move to provide a home on the return of her mate. Even though he had been out of service for six months, he has discovered home life isn’t all he hoped for. “You know,” he admitted, “this may sound petty as hell. But every time my wife mentions our place, she says ‘my apartment’ or ‘my furniture’ or ‘my book case.’ It becomes damned annoying never to hear her mention it as our home.”

Small as it seems, this business of first-person singular only lends credence to the fact that the American female increasingly considers herself an entirely self-sufficient individual—one free from the bothersome necessity of a guy in pants.

While mid-century men complained about women becoming more self-sufficient, dependent, fainthearted housewives were no cup of tea either, as explained in “The Female Fears That Bind a Man” — an article which appeared in a 1965 issue of True: The Man’s Magazine.

“The Female Fears That Bind a Man”

From True: A Man’s Magazine, 1965

I used to know a fellow who worked at a bank in the Midwest. Call him Pete. Pete was not happy with his job. Whether you like your job depends on your personality, and there are many men who get a kick out of the kind of work Pete did. But Pete was a special breed of man who needed something else. He found the job too comfortable. Too secure, too lacking in adventure. “I don’t feel alive around here,” he used to tell me gloomily.

Pete longed for some lustier kind of life, something with a physical and mental challenge, and maybe a spice of danger—“even if it’s only the danger of going broke,” he used to say. But he stuck with the bank year after year because he had a wife and kids to support.

Then one day a white-haired, robust old man walked into the bank, bearing Pete’s salvation. The old man wanted to retire and was looking for somebody to buy his business, a small marina and boat repair shop on one of the Great Lakes.

Pete leaped at the chance. One of the bank executives, a man who perhaps had dreamed the same dream himself, told Pete the bank would understand if he wanted to quit—and, what’s more, would arrange a loan to help him buy the business. For the next few weeks, while figuring out the details of his big move, Pete was a man reborn. There was a new glint in his eye. Then the dream fell apart.

Pete’s wife announced that she’d have no part of this hairbrained scheme. She liked the security his bank job provided. In truth, she would rather spend the rest of her life creeping along a comfortable rut than poke her head out into a bigger, stormier world.

Pete knew enough about divorce and separation laws to realize his wife had him over the barrel. If he left her and went to run the boat shop by himself, alimony payments would complicate his financial problems enormously. Reluctantly, he abandoned the dream. Today he still works at his old job—because his wife was afraid of insecurity.

Women are afraid of all kinds of things. Financial insecurity is only one of them. Women are afraid of physical hardship, physical danger, illness, the dark, lizards, mice and insects to list a few. This is understandable because women are constituted to fear things more intensely than is reasonable, and there isn’t much a man can do about it. But when female fears prevent a man from doing things he wants to do, it’s time to blow the whistle, time for a declaration of male independence from womanish worries!

It’s more than a question of man’s personal satisfactions; the very character of the United States as a nation is at issue. Pete’s wife did damage to Pete, but her kind of thinking—the womanish security-above-all-else philosophy—also does damage to our once lusty country. Multiply Pete’s wife by several million, and you have an attitude that softens the nation’s economic guts.

Women are making their fears felt more and more strongly in the national life. We are becoming increasingly a nation of big corporation employees, men like Pete whose jobs yield safety but don’t lead to glory and high adventure. Women don’t deserve all the blame for this, but they should get much of it. Women are the traditional guardians of home and hearth. Their overriding concern for security, like a great perfumed blanket, has smothered many equally important concerns.

What Men Complained About Women 100+ Years Ago

So the mid-20th-century was not entirely a golden age of women and sex relations. Maybe we need to go even farther back — to the 1800s. Perhaps women were in fact more lovely and upstanding “in the days of lavender and lace.” Alas, as it turns out, men had complaints about the ladies back then, too.

To write 1892’s Girls: Faults and Ideals, author James Russell Miller asked “a number of Christian young men” the following question: “What are some of the most common faults in young women of your acquaintance?” He then compiled their responses into a short book.

Girls: Faults and Ideals, 1892

By James Russell Miller

Several writers have referred to the matter of dress. One says, “Too much time is given by many young ladies to dressing. They scarcely think of anything else.” Another names, “The love of dress, the inordinate desire to excel their companions in this particular,” as among the common faults in young women, adding that it has led many of them to ruin. Another says they like to make themselves attractive by conspicuous colors, and suggests that if they would spend less time in shopping and more in some elevating occupation, for example in making home brighter for brothers and parents, it would be better.

Another fault mentioned is the lack of moral earnestness. “Frivolity, arising from want of purpose in life,” one names, “even the most sacred duties and relations being marred by this frivolousness. The best years of life are wasted in small talk and still smaller reading, tears and sighs being wasted over a novelist’s creations, while God’s creatures die for want of a word of sympathy.” Another names, “Frivolity, want of definiteness of purpose.” Still another says: “The giving of so little time to serious reflection and for preparation for the responsible duties of life. In other words, frivolity of manner, shallowness of thought, and, as a consequence, insipidity of speech, are strongly marked faults in some young ladies.” This writer pleads for deeper, intenser earnestness. “Young women will reach a high excellence of moral character only as they prepare themselves for life by self-discipline and culture.” Another puts it down as “A want of firm decision in character and action,” and says that too often, in times “when they ought to stand like a rock, they yield and fall”; and adds: “The young ladies of our land have power to mold the lives of the young men for good or for evil.”

Some of these letters speak of the common talk of girls as being largely idle gossip; criticisms of absent people; unkind words about persons whom the ladies would meet with warm professions of friendship and fervent kisses if they were to come in a minute later.

One mentions “want of reverence for sacred things” as a sad fault in some young women. He has seen them whispering in the church and Sunday school, during sermon and lesson, even during prayer, and has marked other acts of irreverence.

Others speak of a want of respect for the aged, and especially for parents, as a fault of young women. “How often is the kind advice of a father and mother set aside, just because it goes against some whim or fancy of their own! A desire on the part of a young lady to live in the fashion, to be well-dressed at all hours and ready for callers — how much toil and sacrifice often fall to a good mother from such an ambition!”

One writer notes as a fault in some young women, that they are careless of their good name. “They are not careful enough as to their associates and companions. Some of them are seen with young men who are known to be of questionable moral character. On the streets they talk loudly, so as unconsciously to attract attention to themselves. They act so that young men of the looser sort will stare at them and even dare to speak to them.” In these and other ways, certain young women, this writer says, imperil their own good name, and, I may add, imperil their souls.

In one letter received from a thoughtful young man, mention is made of a “disregard of health,” as a common fault in young women. Another mentions but one fault, — “the lack of glad earnestness.” Another specifies, “thoughtlessness, heedlessness, a disregard of the feelings of others.” Another thinks some young women “so weak and dependent that they incur the risk of becoming a living embodiment of the wicked proverb, ‘So good that they are good for nothing.'” On the other hand, however, one writer deplores just the reverse of this, the tendency in young women to be independent, self-reliant, appearing not to need protection and shelter.

____

Miller compiled a follow-up book called Young Men: Faults and Ideals, in which he asked young women to describe the flaws they saw in their male friends. The ladies’ top complaints were: self-conceit (“their cool self-satisfaction and expectation of worship without any effort to make themselves particularly admirable or worthy of worship”), irritability and grumpiness, selfishness, a lack of respect for women (“In these days, old-time courtesy, true gentlemanliness is often wanting in young men”), using women only for pleasure and amusement, putting women on a pedestal, indulgence in vices, a lack of refinement and manners, and especially a lack of courage and ambition:

“Having opportunities and abilities,” says one, “they waste their lives because they fail to realize the true object and meaning of living.” Says another, “Too many of them seem to have no grand aim, no aim higher than to dress well and be social favorites. They have no energy to make anything of themselves.” Another names as a fault “that love of comfort which makes them too easily satisfied with things, if only the outward conditions are pleasant.” Another says that “young men have time for every amusement and pleasure, but none for study and useful reading. Many of them show little desire for self-improvement.” Several of the writers think that the young men of to-day are not a stalwart type, but are in danger of becoming effeminate, indolent, not fighting the battle of life bravely.

This is one of the perils of prosperous times when everything is going pleasantly.”

Conclusion

One can continue to follow this thread even farther down the line, finding men’s complaints about women dating all way back to antiquity.

Now all this doesn’t prove women (or men) haven’t in fact gotten worse; just because people have had the same complaints over time, doesn’t mean the degree of what they’re referencing hasn’t deepened. For example, during the 1920s, people complained about how vulgar and sexual new dances like the Lindy Hop and Charleston were; today people complain about how vulgar and sexual bumping-n-grinding is. While the complaint is indeed the same, the core of the criticism has demonstrably deepened in degree.

But whether or not women are in fact worse than they used to be, we do know men have never been completely happy with them relative to the times in which they lived. They have always found women wanting — either too dependent and shallow or too independent and domineering.

This fact may elicit one of two responses. On the one hand, it may seem depressing, and justify the idea that the sexes are fundamentally incompatible and that men should deal with women as little as possible.

On the other hand, it’s kind of liberating and comforting to know that one is not living in some uniquely terrible time, with burdens unfaced by past generations of men. That men and women sometimes butt heads then comes to be seen not as some insurmountable problem of the modern age, but as something inherent to the human condition and perfectly navigable. After all, flaws aside, plenty of folks in every age have made a happy, successful go of relationships. Plenty of relationships have failed over the centuries too, of course.

So perhaps the triumphs and difficulties of modern relationships have more to do with the timeless qualities of individuals, rather than “men today” or “women today.” Men have always been happy when they’ve chosen women who try to maximize their virtues and minimize their flaws, and unhappy when they pair with those who embrace the reverse equation. And each type has existed in every era. The same dynamic holds true for the happiness of women and the men they choose as companions.

Indeed, the failings and ideals we alternately criticize and champion in the opposite sex might be better characterized as human failings and merits rather than gender-specific ones. Men and women work for the same virtues and succumb to the very same flaws, but often express and manifest them in different ways.

With this realization comes a new mindset: How can I help my brothers and sisters become their best selves? Because while men and women have complained about each other since time immemorial, at least one difference can be observed between our time and the past: folks used to look on the bright side of things — seeing what was praiseworthy despite the flaws, and only seeking to criticize constructively. Miller notes that “The young men who have replied to my question concerning the faults of young women have done so in the most kindly spirit, for to a noble soul it is always an unwelcome task to find fault: it is much easier to name the beautiful things in those we love than the blemishes.” He reports that the young ladies’ critiques were likewise written “in the most kindly spirit,” and that they “show no glee in the use of their opportunity to tell of the faults they have seen in young men.” Miller makes a point to let his readers know that the young women’s complaints should not be taken to mean there weren’t “many noble and beautiful qualities in the young men in whom some faults have been seen”:

“On the other hand, there are thousands of young men whose lives are rich in the elements of truest manliness, whose characters are radiant with the luster of ‘whatsoever things are honorable,’ and who are making for themselves records worthy of all praise. This is the golden age of young men. The faults that are here noted are lesser or greater blemishes on noble lives, pointed out in sincerest friendship, in the hope that by correcting them these lives shall rise to still fairer beauty and yet manlier strength.”

The skeptic will likely say that maybe the late 19th century really was the golden age of men and women, making such mutual kindness and respect warranted. But that then begs the question: did men and women formerly appreciate each other more because each sex was better and nobler, or were they better and nobler because men and women appreciated each other more?

In other words, might it not be possible that in only concentrating on each other’s faults and failings, men and women alike sink to these abysmally low expectations? And that if we criticized each other only in the spirit of friendship, and set common goals for greater virtue and excellence, we all might rise to greater beauty and strength?

For as Miller advises:

“While we must not be blind to our faults and imperfections, the best way to deal with them usually is not to try to remedy them one by one, but to seek larger abundance of life, thus expelling them by the power of new affections…Without doubt the true method in the culture of character is not to give too much thought directly to one’s defects and faults, but to seek to have the heart-life pure, strong, and full, so that it will throw off the blemishes and flaws, and fill up what is lacking in the outer life.”

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a tweet or join the discussion on Facebook!