MacGyver is stuck in the attic of a house. Bad guys are coming up the stairs and about to bust into the room. The only way out is through a window, but it’s a ways up, and angry Doberman Pinschers await below. MacGyver searches through the attic and grabs a bottle of cleaning fluid, mothballs, a telescope, a pulley, a rope, and a metal rod. He hastily assembles a rocket-propelled harpoon from the seemingly random materials, which he then uses to create a zip line to a tree outside. Just as the bad guys breach the room, he glides away to safety.

Awesome, right? This was just one of the many improvised gadgets and explosives MacGyver created during the 7-year run of the television series that bore his name. The show was so successful and memorable, that despite being canceled in 1992, it remains one of the most recognizable touchstones of popular culture and has even entered our lexicon; to jury-rig something using only the materials you have on hand is to “MacGyver” it.

The “MacGruber” SNL parody, which improbably became a full-length film, has lent MacGyver a cheesier and more satirical air in recent times, but there’s still something about the character that strongly resonates. And that resonance actually goes a lot deeper than pop culture; it in fact points to an universal archetype of manliness, and a trait of masculinity that has been valued and celebrated across times and cultures: improvisation.

A Case Study in Masculine Improvisation: The Cretan Glendiots

To understand how and why the ability to improvise has, and continues to be, considered a particularly compelling and manly trait, let us travel to the island of Crete off the coast of Greece. It was here in the 1970s that anthropologist Michael Herzfeld studied the culture of masculinity in a small mountainous village he dubbed “Glendi” (the name was a pseudonym, to protect the confidentiality of its residents). The Glendiots were a pastoral people, and because of the remoteness and hardscrabble nature of their village, had retained much of the traditional code of manhood that marked cultures around the world for thousands of years. The men had a reputation as strong, independent, outlaw-types, and stealing sheep from neighboring villages’ flocks was a central part of demonstrating their manhood; the practice was not considered by them to be immoral, but rather a way to build alliances (there’s a lot to unpack on this subject, and as the culture of shepherds as a whole, especially contrasted with that of farmers, is such a fascinating topic, we’ll cover it in full down the line).

It is in fact a Glendiot idiom that gave to us the distinction between being a “good man” and “being good at being a man.” And part of earning the latter distinction was mastering the art of improvisation. Women assuredly improvised too, but more often practiced this skill within the privacy of the household. Men were expected to demonstrate their adeptness in the public arena, so that others could judge their prowess. Such demonstrations were made through sheep raiding, dancing and singing contests, drinking and toasting, telling jokes, showing hospitality to guests, and playing cards. In such things, Herzfeld writes in The Poetics of Manhood, it wasn’t enough simply to do the minimum and stick with the basics; to show you were good at being a man, you had to invest your actions with “flair and distinctiveness” and achieve:

“performative excellence, the ability to foreground manhood by deeds that strikingly ‘speak for themselves.’ Actions that occur at a conventional pace are not noticeable; everyone works hard, most adult males dance elegantly enough, any shepherd can steal a sheep on some occasion or other. What counts…is a sense of shifting the ordinary and everyday context where the very change of context itself serves to invest it with sudden significance. Thus, instead of showing what men do, Glendiots focus their attention on how the act is performed.”

As is the dynamic of all male groups, Glendiot men both competed as individuals to achieve status within their village, and banded together to compete for status with other villages. Demonstrating one’s ability to improvise was one of the surest routes to achieving high standing as individuals and as a group. Honored was the man who didn’t seem as if he had planned out every move of a successful action ahead of time, and appeared to “have ‘chanced’ (etikhene) upon the flock he raids, the verse he suddenly thought up, the food he is able to serve his unexpected guests.” To the Glendiots, Herzfeld observes, “flexibility and an ability to make the best of any situation are key components in the definition of the true man.”

Why would this be so? Why would the ability to improvise be considered such a valuable and honored trait amongst the Glendiots, and other cultures as well? There are several reasons.

Why Improvisation Is a Valuable and Manly Trait

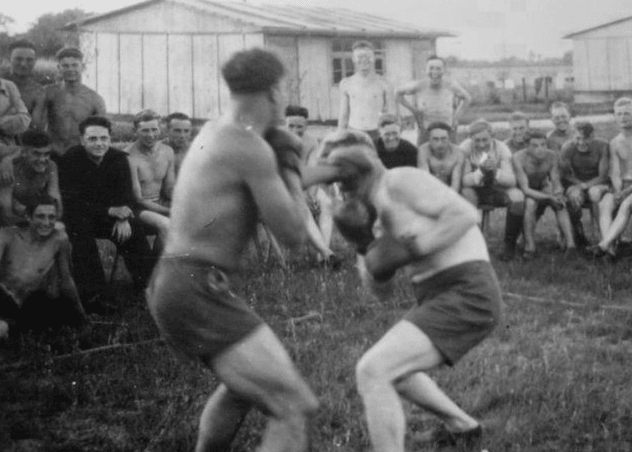

Offers an advantage in battles, of all kinds.

“The qualities that make a good soldier are, in large part, the qualities that make a good hunter. Most important of all is the ability to shift for one’s self, the mixture of hardihood and resourcefulness which enables a man to tramp all day in the right direction, and, when night comes, to make the best of whatever opportunities for shelter and warmth may be at hand. Skill in the use of the rifle is another trait; quickness in seeing game, another; ability to take advantage of cover, yet another; while patience, endurance, keenness of observation, resolution, good nerves, and instant readiness in an emergency, are all indispensable.” –Theodore Roosevelt, Outdoor Pastimes of the American Hunter

In every kind of competition, the man who can improvise has an edge. You can train all you want, and make the most thorough of plans, but you can never predict with certainty all the moves your opponent will make (including the wrenches thrown by Mother Nature). As the military maxim goes: “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” Or as Mike Tyson memorably said: “Everyone’s got a plan ‘til they get punched in the mouth.”

The ability to adapt to changing circumstances is key in winning any battle, including those of the non-physical variety. For example, the Glendiots had singing contests where men traded improvised verses back and forth. Those who crafted a clever new idiom, or used a familiar one in a fresh context, garnered the respect of their fellow villagers. Predictability was considered a flaw, and it was an insult to imply that one’s opponent was a hack who didn’t have the cojones and ingenuity to play with convention and create something original, clever, and effective.

The same dynamic exists in everything from debating contests to rap battles to musical “duels.” Jazz has always been considered a distinctly masculine genre of music because of its emphasis on competition and improvisation; piano players in 1920s New York, for example, would often muster for rousing back-and-forth “battles,” with each man trotting out his best stuff in late-night cutting sessions. To come out on top, you had to have a readiness with the notes, and an ability to riff on whatever was happening.

The same dynamic exists in everything from debating contests to rap battles to musical “duels.” Jazz has always been considered a distinctly masculine genre of music because of its emphasis on competition and improvisation; piano players in 1920s New York, for example, would often muster for rousing back-and-forth “battles,” with each man trotting out his best stuff in late-night cutting sessions. To come out on top, you had to have a readiness with the notes, and an ability to riff on whatever was happening.

The competitive nature of contests of all kinds brings up another manly virtue of improvisation: embracing risk. To improvise takes courage — you have to step in the arena and hope that whatever you need will come to you in the moment, accepting that, if it doesn’t, you will royally fail.

Enhances the ability to adapt to challenging circumstances and uncertainty.

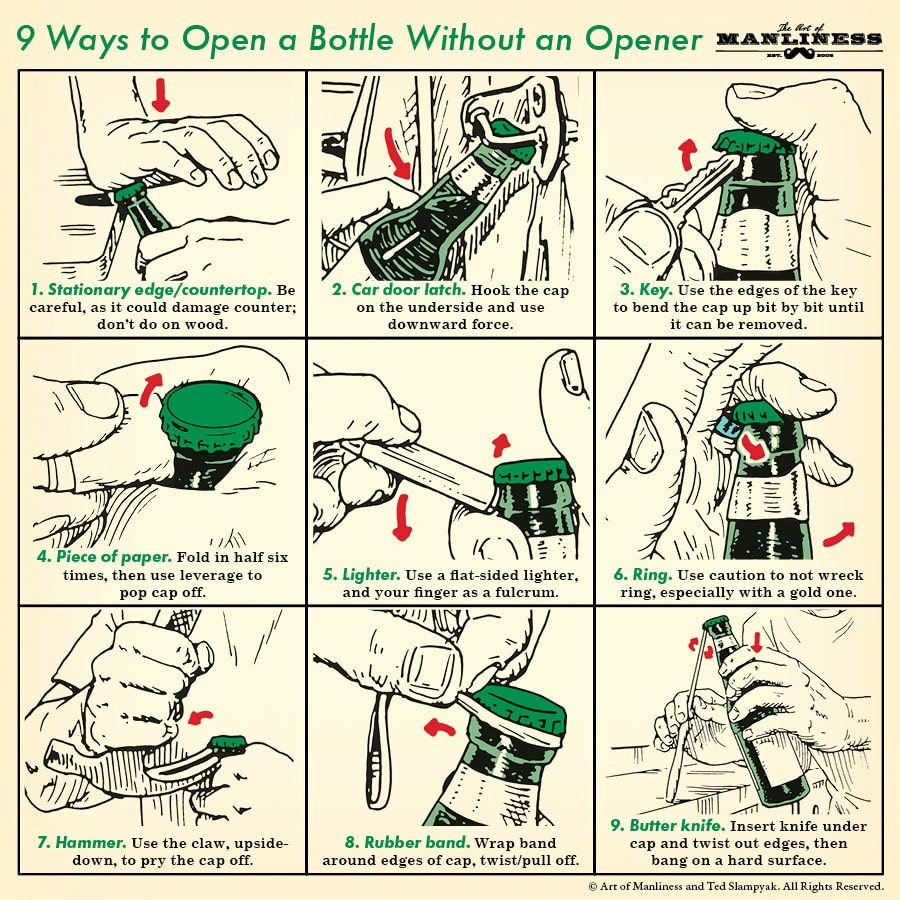

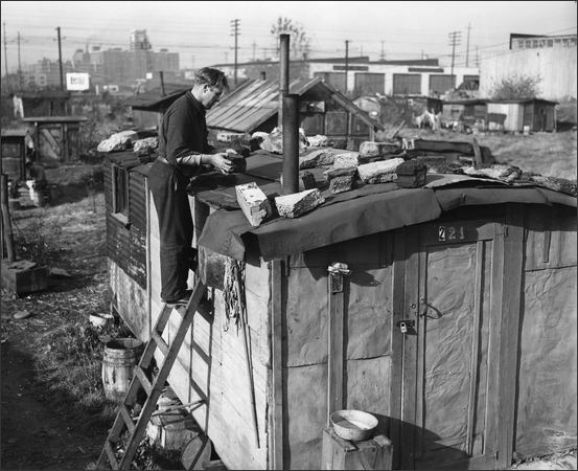

It is not so surprising that the Glendiots, who lived a rugged, hardscrabble life, would “applaud in word and deed: the serendipitous response to hardship and poverty, the ability to turn the meager gifts of chance to advantage.” The man who can make the most of whatever he’s got is going to be better able to fulfill his central roles as a man, and be the superior protector and provider. We respect the guerilla warrior who is able to take on forces that have much more equipment, weapons, and money — who is able to create inventive ways to trap and weaken a far greater foe. We imbue much more heroism into the David than the Goliath. Likewise, we have more respect for the man who can catch a fish with an improvised spear or dissemble a cell phone and use it to survive in the wild, than one who’s got a backpack full of high-tech gear.

The reason we respect those with the ability to improvise weapons and gadgets is that we know life is incredibly uncertain. We may be living in luxury now, but might one day be struggling through a harsh environment. In such a situation, the resourceful man — the man who is able to “make the most of whatever chance offers” — is the man we want on our team, and that we hope to be ourselves. He’s the guy who will get us through.

The ability to improvise speaks not only to a tangible skill for jury-rigging, but also to a tough, flexible, resilient mindset. A man who has confidence that he can find a way out of a challenging circumstance, even when prospects are grim, is someone far less likely to break down in the heat of crisis.

So too, improvisation doesn’t just help in combat or survival situations. A man who can find new ways to stretch a budget, repair something without buying an expensive part or calling in a professional, figure out a way to defuse a tense dispute between friends, think of a comforting word to say to a distraught relative, or come up with an alternative date when the one he plans go awry, carries a lot of value.

For these reasons, Glendiot men actually welcome challenges, and “rejoice in the very uncertainty of their lives, since it is this that gives them the chance to demonstrate their improvisational skills.” And it’s true: there can be something uniquely satisfying about making something out of seemingly nothing — more so than if you had a ton of options and materials to work with. It feels good to know you have a bit of the MacGyver in you — that come what may, you are always prepared.

Sharpens the ability to seize an unexpected opportunity.

Improvisation isn’t only valuable as a defensive skill that allows you to effectively react to challenging circumstances. Being resourceful and able to think on your feet also allows you to be proactive in grasping positive opportunities. The Glendiots believed that “the greatest achievements are those that entail seizing some quite unexpected chance.”

Let’s say your boss calls on you to make an impromptu presentation to an important client. Could you ace it? Or a woman unexpectedly responds to your advances and wants to go somewhere to hang out. Could you figure out what to do next?

When Theodore Roosevelt was president, an autographed copy of the poem “Opportunity” by John James Ingalls was said to be the only thing besides a portrait to hang in his executive office in the White House. It sums up the importance of being able to seize the chances that suddenly appear, and just as quickly disappear, from our lives:

Master of human destinies am I!

Fame, love, and fortune on my footsteps wait.

Cities and fields I walk; I penetrate

Deserts and seas remote, and passing by

Hovel and mart and palace—soon or late

I knock unbidden once at every gate!If sleeping, wake—if feasting, rise before

I turn away. It is the hour of fate,

And they who follow me reach every state

Mortals desire, and conquer every foe

Save death; but those who doubt or hesitate

Condemned to failure, penury, and woe,

Seek me in vain, and uselessly implore.

I answer not, and I return no more!

Creates a tool that can quickly shut down a naysayer and/or resolve conflict without violence.

Herzfeld found that being able to offer a clever, improvised quip or insult had the perhaps counterintuitive ability “to restrain physical violence.” This was because responding to a verbal insult “with knife or fist would demean the assailant by suggesting that he was incapable of responding with some witty line of his own.” In other words, if you insult an opponent in a really clever way, it limits his options as to how to retaliate. He could still sock you, but lashing out physically shows he can’t reply with an equally witty retort, which dishonors him in the eyes of his audience. He must remain silent, and take his verbal licking.

Even if violence is unlikely to occur in a dispute, a sharp, witty quip can quickly shut down a heckler or critic, leaving him speechless. Winston Churchill, for example, was a master of this art!

Thus, being able to throw out a really clever put-down can sometimes end an argument and vanquish a foe without it coming to blows. This makes improvisation an especially valuable tool for the weaker, less formidable man, and indeed, men who haven’t been blessed with physical prowess have often honed their humor and wit into a potent weapon.

Tailored communication = greater effectiveness.

Have you ever gotten an email where you can tell the writer was just sending the same template to multiple people, and simply changing a few details like your name? Or have you attended concerts from the same artist in multiple cities, and heard them give the exact same shoutouts and banter to the audience? In these instances you probably felt like the sender/artist was less sincere, and it weakened your affinity for them.

Humans prefer communication that seems spontaneous — that’s tailored to the specific circumstances of the time and the audience. Someone who uses the same speech, pick-up lines, jokes, sales pitch, etc. in every situation, often finds that their banter falls flat because it doesn’t best fit the exigencies of the moment. A man who has the core elements of what he wants to say in mind, but then tailors his message to the changing circumstances, is the far more effective communicator.

Creates a memorable, impressive reputation.

The abilities gained by a man who masters improvisation don’t just pay off in the effective actions he is able to perform, but the reputation those actions create for him.

Classically, honor meant having a reputation worthy of admiration and respect. It was earned by winning kudos from one’s fellow men. Achieving such a reputation is useful, because it makes other men want to be your friend and ally, instead of having you as their enemy. And it acts as a deterrent to attacks, as a man with a reputation for strength, skill, and ingenuity is not someone others want to mess with.

In Greek and Cretan culture, a man’s reputation, his whole identity, was staked on the actions he took. As Herzfeld writes, “Insofar as he can foreground the quality of his ‘doing,’ Glendiots are able to appreciate what he ‘is.’” Doing deeds that demonstrated improvisation was an especially effective way to build an honorable reputation, because such actions surprise, impress, and even shock others, and are thus very memorable. Improvised action effectively served notice to a man’s audience or opponent of the skill, ingenuity, and quick-thinking he was capable of. As Herzfeld writes, in all competitive domains, “a man’s every action must proclaim itself a further proof of his manhood. An action that fails to point up its own excellence is like the proverbial tree falling in an empty forest.”

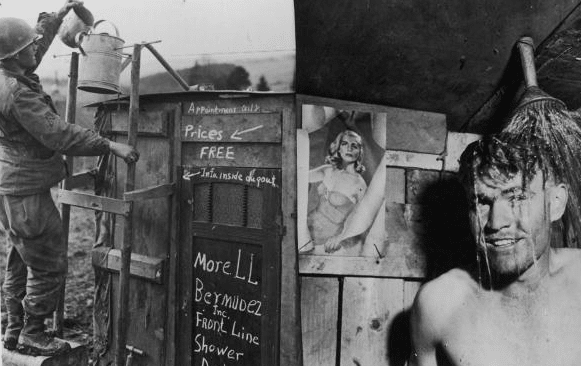

The Bread Helmet: Memorable masculine improvisation at its finest, if not its most functional.

Impressing an audience wasn’t just about pride, but turning an improvised escapade into a story that one’s peers would tell and re-tell — one that would burnish his reputation far and wide. “Remember that time when that dude made a rocket-propelled harpoon out of a telescope and moth balls?” Once such a story got around, competitors would think twice about challenging that man. Not to mention, the ladies would be pretty intrigued (if not by the gadgetry, then definitely by the mullet).

Think about the famous quips of Winston Churchill that still get passed around today. When Herzfeld shared some with the Glendiots, they were so impressed and tickled by Churchill’s improvisational wit, they would make the anthropologist repeat the stories over and over again.

Imbues life with meaning.

If no one was around to witness your impressively improvised feat, you had to be able to tell the story in a memorable way yourself — another skill that involved the mastery of improvisation! In Glendi, men were judged not only on the action, but how well they spun a narrative about it. In turn, the act itself and the subsequent story folded back on each other, as Herzfeld explains:

“If the narratives reproduce the quality of raiding, moreover, it is also true that the raids in turn possess some of the expressive properties of narrative. Glendiot idiom recognizes this in the use of istoria, ‘tale,’ for any exciting event, be it interpersonal violence or adventure in the foothills. ‘We’ll have ‘tales’’ means that serious quarrels are anticipated. But the term is particularly apposite for animal raids…As the shepherd with whom I began this chapter recalled: ‘I remember the first time I went on such a tale.’”

Glendiots believed that an embrace of improvisation, the relishing of the chance to be resourceful and take advantage of serendipity, made “an adventure out of every encounter.” They also felt it added simasia or meaning to life.

Glendiots regarded life “as a barren stretch of time, a blank page on which the genuine poet of his own manhood must write as an engaging an account as he can.” The more one is able to improvise things like humor, better ways to spend one’s time, and how to pull off an exciting escapade, “the more successful the transcendence of the mundane existence and the more pleasing aesthetically the resulting memory.” For this reason, Glendiots believed that “The ability to play with conventions in aesthetically intriguing ways, and above all to seize opportunity from unpromising materials, is what generates simasia in particular contexts.”

Part of why improvisation creates meaning is that in bending “fickle chance to the actor’s own ends and the comfort of his guests” he reveals “an infinite swath of possibilities.” Improvisation takes words and materials out of their ordinary context, and puts them into a new one; “I never would have thought an egg could have been used to fix a radiator!” The audience of such an act not only sees the improvised object in a new light, but it inspires them to look at everything else from a different perspective as well; what other interesting opportunities might be hiding in the seemingly mundane?

Another part of the meaning improvisation imparts to life, is the way is puts a man in the role of competitor with death itself. In Greek symbolism, Herzfeld explains, “Death is a talented thief” who steals you away from mortality. This is not just meant literally, as in final, physical death, but also in the slow, everyday crushing of one’s spirit and joy. To fight back, to take the unpromising, meager materials given to you by circumstance, and turn them into something meaningful and successful that rises above the ordinary and adds something to your life, and to the lives of others, is then in Glendiot idiom to “seize a bad hour from death.”

Think about the most memorable experiences of your life. Were they not often the times where things went awry or the going was tough, but you managed to make the most of it anyway? “Death” had conspired to rob you of having a good time and a meaningful experience, and had you given in, he would have won. You would have lost those hours or years forever. But through improvising a plan B, you snatched them back from Death’s wilting touch.

“A well-lived life,” the Glendiots thus say, “is a life of well-stolen moments, each one unique.”

__________

Source:

The Poetics of Manhood by Michael Herzfeld