Spectator sports are a multibillion dollar industry. Hundreds of millions of people watch sports worldwide whether on TV or in person, and the personal lives of athletes are fodder for news stories and television shows. Star professionals make huge salaries, plus they rake in boatloads more with endorsement deals.

But what’s interesting is that the money-making mania of today’s sports world was kicked off in the 19th century by the riveting, action-packed sport of….walking?

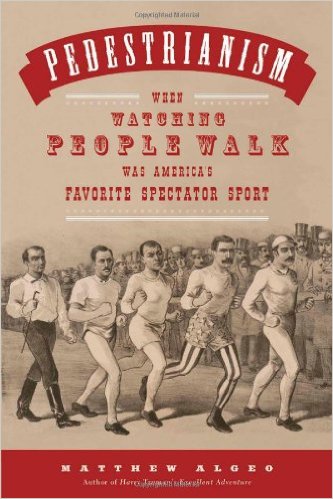

In Pedestrianism, writer Matthew Algeo takes a look at the long-forgotten sport of pedestrianism or competitive walking. During the 19th century, it was the absolute bees knees. Tens of thousands of people would fill arenas to watch mustachioed men compete for giant paydays by walking in circles for six days straight. While the history of pedestrianism is interesting in and of itself, Algeo also shows how it laid the groundwork for modern spectator sports.

In today’s podcast, Algeo and I discuss some of the more interesting and larger-than-life characters who competed in this old-time sport, as well as the ways in which it birthed the money-fueled sports industry of today. I think you’ll find the conversation anything but pedestrian!

Show Highlights

- How a bet on the 1860 presidential election kickstarted the pedestrianism craze

- The insane distances walkers would traverse

- The bloused shirt-wearing, cane-carrying superstar of pedestrianism

- How the first doping scandal in sport occurred during a 19th century walking race

- The weird rules of pedestrianism

- How professional pedestrians paved the way for the mega-paid professional athlete

- Why watching people walk for days on end was so popular in the 19th century

- How pedestrianism was the first sport in America to break the “color barrier”

- Why pedestrianism declined

- How you too can take part in an old-time pedestrianism race today!

- And much more!

Pedestrianism was a fun and fascinating read. I found myself laughing out loud at several points. What’s more, by taking a microscope to a forgotten 19th century sport, Algeo is able to show readers the cultural currents of the 19th century that gave rise to many aspects of modern spectator sports.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Today, sports is a multi-billion dollar industry: football, basketball, soccer, baseball. I mean thousands upon thousands upon thousands of people come to watch these sports. They watch them on television. The athletes are making millions of dollars, hundreds of millions of dollars. There’s salary plus the endorsement deals that go along with it. Here’s the thing. This whole mega sports industry that we have today started with the super exciting sport that happened in the 19th century of competitive walking. Yes, I’m being serious.

My guest today dug up this long forgotten sport that really kicked off the modern sport era. His name is Matthew Algeo. He wrote a book called “Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport.” It’s a fascinating look at a lost bit of American history that has a wider influence on sport today. Everything that we know about sport today with the endorsement deals, super high salaries, super high payouts, thousands of people watching a sport, this all started with competitive walking, which is really bizarre.

It happened during the late 19th century during a time that I like. It’s when boxing was coming to rise, John L. Sullivan. Teddy Roosevelt was coming to power. You had the rise of mass media, the rise of consumer culture, and all these things came together around competitive walking. Well, today on the podcast, Matthew Algeo and I discuss this long forgotten sport and how it influences sport today. It’s a really fun, interesting look into a forgotten bit of history. Without further ado, “Pedestrianism” with Matthew Algeo. Matthew Algeo, welcome to the show.

Matthew Algeo: Thank you. Thank you for inviting me.

Brett McKay: Well, you’re welcome. The reason I invited you, because I forgot where I heard about your book, but it’s talking about this obscure sport that I knew nothing about even though Gilded Age American is one of my favorite parts of American history. You have the rise of price fighting. We’ve got John L. Sullivan, the masthead of our website, Teddy Roosevelt, all this stuff, but I had no idea that there’s a sport called pedestrianism, which is just basically walking, was the most popular sport in American for about 40 years. I’m curious, how did you come across this bit of forgotten American history?

Matthew Algeo: Yeah, it’s definitely been forgotten. I was actually researching a book about eight or nine years ago about the 1943 merger of the Steelers and the Eagles. You might be aware of this. They were the Steagles for a season because in 1943, during WWII, the teams were so short of players they had to merge two teams, so they merged the Steelers and the Eagles. I was writing a book about the Steagles. While I was researching that book I did some research on the history of spectator sports in the United States. I’m like you, I’m a big fan of the Gilded Age. I love the 1890s, the 1880s.

I was blown away to realize that, when I was researching the history of spectator sports, in the 1880s and 1890s this sport of pedestrianism was the most popular spectator sport in the United States. Thousands, tens of thousands of people would fill arenas to watch guys walk around a dirt track for days at a time. This was just the most entrancing, fascinating thing that was going on in the Gilded Age. People bet on this. I mean it’s funny right now we have all this controversy about fantasy sports and online betting with fantasy sports. I mean this was the original fantasy sport. People would bet on anything about these guys. Who would be the first to walk 100 miles? Who would be the first to drop out of the race? It was just like the most amazing spectator sport in the United States for, like you said, a really short period of time, but for that period of time in the 1880s and 1890s, it ruled.

Brett McKay: Yeah, like the New York Times would write about it. The National Police Gazette, we’ve talked a bit about that on the show and the website before, they were …

Matthew Algeo: They loved it.

Brett McKay: They love the pedestrianism.

Matthew Algeo: They love it.

Brett McKay: It was like a freak of nature was really what it came down to.

Matthew Algeo: Well, one of the most popular form of pedestrianism was the six-day race. Guys would walk for six days beginning … you couldn’t because back then, of course, on Sundays you couldn’t have any entertainment.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Blue Laws.

Matthew Algeo: Blue Laws, exactly. So the races would begin right after midnight Monday morning and then continue right up until midnight Saturday night, so it was six days long. During this time you would have the newspapers covering the event. They would be posting updates all over the city on billboards, and people would just be following it. They would have extra editions of the newspapers published to show who was in front, who was leading at that time of the day, on Monday morning, on Tuesday afternoon, on Wednesday afternoon. It really was just an amazing cultural phenomenon at the time.

Brett McKay: You said it was a high stakes game, like lots of money was … We’ll talk about how much the purses were for these competitions, it was insane, but the gambling that was involved. What’s funny about pedestrianism is that it got started on a bet. Tell us a little bit about the story of how pedestrianism got its start.

Matthew Algeo: Sure. It was the 1860 presidential election. Of course, Abraham Lincoln was the Republican candidate in 1860. There were about three other candidates, the Democratic Party was split. There was a guy in Boston, a guy named Edward Payson Weston. He bet a friend that Lincoln would lose the election in 1860. Of course, Lincoln wins the election in 1860. The terms of the bet though were unusual. Weston had to walk from Boston to Washington in time to see the inauguration of Lincoln in March of 1861, so Weston did this walk. It’s the middle of winter. He’s walking from Boston to Washington. It really caught the nation’s attention. He became a very popular figure in the media. The newspapers covered this walk: Would Weston make it to Washington in time to see Lincoln’s inauguration?

Weston was actually about four hours late to the inauguration. He didn’t win the bet. Well, he lost the bet. He didn’t fulfill the wager, but he became such a sensation that people all over the country wanted to see Weston walk. I mean it blows your mind, but people came out just to see him walk through their town when he was doing this walk from Boston to Washington. He figured there’s got to be a way I can monetize this, and so he started taking his act on the road. He walked indoors, in rolling skating rinks. He tried to walk 100 miles in 24 hours, that sort of thing. That’s how he became a very famous pedestrian. He started the whole idea of competitive walking in the United States.

Brett McKay: He was actually a showman, which I thought was really interesting. He wasn’t really much of a … I guess he was an athlete because he was able to do these things, but he brought a bit of showmanship into the sport.

Matthew Algeo: I like to say he was the Ab- … He was the Abraham Lincoln. He was the Muhammad Ali of the 1870s. He understood just instinctively the connection between entertainment and sports. For instance, he would walk 100 miles in 24 hours, which is really an incredible feat. It’s hard to do even today, but, when he did it, he wore long velvet coats, and he always carried a cane. He wore a top hat, and he always wore a necktie or a cravat. He understood that you had to play to the crowd. I mean it was almost a head of its time in the way he understood that you really had to entertain at the same time that you were performing an athletic feat. Like I say, it’s a lot like Muhammad Ali.

Brett McKay: This was during the Gilded Age. This is really when mass media was starting. I guess he was one of those first people who intuitively understood the power of mass media. I think Teddy Roosevelt was the first president that really understood the power of mass media. I guess Weston was the first athlete who understood the power of mass media that catapulted him to fame and riches.

Matthew Algeo: It’s funny. I’m actually working on a book about Roosevelt right now and how he played the media. Weston really played the media so well. I don’t mean that in a negative way. He knew that the picture on the front page of the paper was more dramatic if he was wearing a long, flowing coat and carrying his gold-topped cane. He really understood how entertainment worked, how sports worked, how business worked. He was one of the first athletes to really become interested, invested in his own business. He negotiated his own contracts. This was unheard of at the time. Most athletes were sort of led along by guys who took advantage of them, but Weston wasn’t like that. He was kind of the first generation of athletes who really knew how to capitalize on their fame.

Brett McKay: How did it transition? How did it start from Weston doing this bet basically to walk all the way to Washington, DC, and transform into this thing where there was competitive leagues. There were matches, and money was at stake. How did that transition happen? Here’s the other … why did it happen? What cultural forces were going on at the time that allowed pedestrianism to be the most popular spectator sport in America?

Matthew Algeo: Well really, one of the things was that roller skating became very popular. The roller skate was invented, the kind we know today with the four wheels on the bottom that you can lean and turn, and roller skating rinks popped up all over the country. These were really kind of the first enclosed public spaces, and so there were these venues that were sitting there with nothing to do except rolling skating. Weston, who had just walked from Boston to Washington, realized that all these people wanted to watch him walk. All these roller skating rinks were out there, and so he would go to a roller skating rink, and he’d set up a track. It might be 50 laps to a mile. These were tiny, little roller skating rinks. He would go in there, and he would charge people 10 cents to go watch him walk 100 miles in 24 hours, that sort of thing.

It was this weird convergence of indoor spaces and Weston, people like him, seeing how they could capitalize on these indoor, public spaces for the first time. You also have to remember at the time, we’re talking about after the Civil War, for the first time people have a little extra money in their pockets. You see industrialization coming in. People have a little extra time on their hands, extra time, extra money. These indoor rolling skating rinks, Edward Payson Weston traveling around the country walking 100 miles in 24 hours all over the country and so all these things came together and turned what was this weird bet that he could walk from Boston to Washington into a professional sport.

Brett McKay: I guess at the time baseball was just getting started, so that wasn’t a factor. They weren’t competing with baseball. Prize fighting was around, but that was an underground sport and looked down upon, so walking …

Matthew Algeo: You also …

Brett McKay: Oh, go ahead.

Matthew Algeo: … have to remember baseball sort of had a bad reputation. Boxing, of course, had a bad reputation. Pedestrianism was a wholesome sport. It was walking. What could be more wholesome than walking? So really it was this void that Weston filled when he started going around the country staging these walking exhibitions that said you could bring the family. It was family entertainment, 5 or 10 cents a person, and you could take the family to go see it. You would never take the family to go see John L. Sullivan. Even baseball at the time had a bad reputation. So it really was the first family entertainment, mass entertainment in the United States in 1870s, 1880s, 1890s.

Brett McKay: Besides having these exhibitions where people would pay to watch, it evolved to becoming a sport where there were like belts. They created a belt system like prize fighting. Can you talk a little bit about what I thought was just mind boggling was the amount of money the purses that these walkers, these pedestrians could win? Can you talk a little bit about some of the prizes that were won by some of these athletes?

Matthew Algeo: You’ve got Weston, and he’s going out. He’s walking these exhibitions. Of course, people see how much money he’s making, and competitors arise naturally. The biggest competitor was a guy named Daniel O’Leary. He was an Irish immigrant, and he figured if Weston can walk 100 miles in 24 hours, I can walk 105 miles in 24 hours. Eventually they met in a race, and it was a six-day race as we mentioned earlier. That was as long as you could race. The first big race was in Chicago. This sort of morphed into these six-day races involving all sorts of competitors, from the United States and from Great Britain.

As you mentioned, the payouts on these races were tremendous, because, think about it, it’s a six-day race. You’re at the first Madison Square Garden. They might have 10,000 seats, but it’s continuous. It’s for six days, and so people are coming and going constantly. You could have 500,000 people maybe come and see this race over the course of a week because you might come in and see it for five minutes and leave. Everybody was paying 50 cents or $1.00 a ticket. The winner of the race might receive $25,000, $30,000, $40,000, which today is a million dollars. I mean this is for six days’ work. Whoever won would get a million dollars for six days’ work. This actually stands up to what you see for professional athletes today because a million dollars for a week is $50 million for a year. That’s a pretty good baseball player right there even today.

Brett McKay: Besides the payouts, did some of these athletes get sponsorship deals like modern athletes do?

Matthew Algeo: Yeah. What was interesting, you mentioned the Police Gazette before. You guys know all about the Police Gazette, but they were one of the big sponsor because they covered the races. People who subscribed to the Police Gazette loved pedestrianism. They had a guy that they paid, I think, $2,000 to wear a shirt that just had the Police Gazette logo on it during a race. I mentioned Dan O’Leary earlier. He was the spokesperson for a brand of salt. “When I need to re-salt, I use Tiger Salt.” These guys, they were some of the first athlete spokesmen in the United States. It’s the beginning of this whole sports industrial complex.

Brett McKay: There were also the first on sports cards, like the cigarette cards.

Matthew Algeo: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Cigarette cards really came out … started beginning in the 1870s and 1880s. I’ve got a couple of them. Some of the first athletes featured on these sporting cards were pedestrians. Frank Hart who was actually one of the first famous black athletes in the United States … He was an African American who won a couple major pedestrian events. He’s probably the first African American ever featured on a trading card in the United States. All these guys are forgotten now. Nobody remembers them. That’s probably why nobody’s buying my book. I really think that they were a huge part of American sports history, and I really think they need to be remembered.

Brett McKay: Tell us a little more about Frank Hart, because I thought this was really interesting. This was before, I guess, Plessy v. Ferguson.

Matthew Algeo: Yes.

Brett McKay: People always had this idea that sports has always been segregated, but there was a time right before Plessy v. Ferguson when separate but equal was the law of the land where you had black athletes who were competing and doing really well in competitive sports in America. Can you tell us a little bit more about Frank Hart?

Matthew Algeo: There were even black baseball players in the 1880s and 1890s. You’re right. Plessy v. Ferguson ended everything. It ended any kind of integration that was going on. The beauty of pedestrianism was that anybody who could walk could do it, and almost everybody can walk. Black people can walk. Chinese people can walk. White people can walk. It was amazing the variety of people you had in pedestrian events because anybody who could walk could take part. It didn’t matter what your race was, what your color was.

People tend to forget this that in the Gilded Age, you had this weird period between Reconstruction and Plessy v. Ferguson, as you mentioned, where there was a wide-open field, really. I make the argument in the book that things were a lot better for African American athletes between Reconstruction and Plessy versus Ferguson than they were between Plessy and Jackie Robinson. I mean black people could take part in sporting events with white people. Frank Hart was one of those people, an African American, who took part in these events, and he won several six-day races. His picture was on the front page of the New York newspapers. It was amazing for an African American at that time to do what he did. It’s a shame that it really ended with Plessy versus Ferguson.

Brett McKay: He won a lot of money, too.

Matthew Algeo: These guys won so much money. You really don’t appreciate but winning $12,000, $15,000 in 1889 was like winning half a million dollars today. Really for six days work, you could take half a million dollars home. If these guys won two races a year, they won a million dollars a year. I mean it was amazing.

Brett McKay: I guess something we really haven’t talked about is how these races actually went down. A lot of them were six-day races, but they weren’t walking continuously for six days. How did the whole walking match occur, and what were some of the rules that governed these events?

Matthew Algeo: For a walking match, strictly, one foot had to be on the ground at all times, heel, toe, heel, toe, just like today. In the Olympics you have 10, 50 kilometer walking matches. You see the way people walk, that funny, swiveling in their hips kind of walk. That’s how people walked. The match would begin, as a I mentioned earlier, right after midnight on Monday morning. Typically it would continue right up until midnight on Saturday night. There would be tents erected in the middle of the track. There’d be a dirt track on the floor. It’d be maybe an eighth or a seventh of a mile around. It’d be inside an arena. Almost always these were indoor events. Whoever walked the most miles over those six day would be the winner. You could stop whenever you wanted. You could go rest in your tent. Most people ate while they walked. They might eat some greasy eel broth or something like that. It wasn’t really the kind of nutrition that people take today. Whoever walked the most miles in six days was the winner. That was the most common race, the six-day race.

Brett McKay: I thought it was really interesting how they kept themselves … some of the things they did. You mentioned the greasy eel broth, but I guess champagne was a really popular drink to keep you going.

Matthew Algeo: They thought alcohol was a stimulant, and so a lot of guys would drink a lot of alcohol and then sometimes literally fall off the track. It was just amazing. It took them a while to figure out that you probably shouldn’t be drinking during the race. The guys who took it most seriously, really, they did training. I tend to make fun of them or whatever, but the guys who were very serious about it, they did a lot of training. They did a lot of running, a lot of jogging, that sort of thing. I mean they were athletes on a par with the athletes of today.

Brett McKay: Speaking of how pedestrianism really laid the foundation of modern sport in America, you talked about how pedestrianism had America’s first doping scandal. I thought this was really funny, too.

Matthew Algeo: Yeah. Edward Payson Weston, who we had mentioned earlier, he took part in a race in the UK. It was discovered that he was chewing coca leaves. This was, of course, a stimulant, but at the time there were no rules. I mean this was one of the problems with pedestrianism and one of the reasons it died is that there was no governing body of pedestrianism. There was no commissioner of pedestrianism. There was nobody to really take control of the sport, and so when Weston was found to be chewing these coca leaves, there was nobody to enforce any rule to say it was wrong. There’s nobody to tell him that he should be expelled from the sport, that sort of thing. So it really went by that Weston got away with this. He later insisted that it gave him no competitive advantage. Of course, that’s what everybody says when they chew coca leaves, I guess.

Brett McKay: When they get caught, right?

Matthew Algeo: Yeah.

Brett McKay: You mentioned there was a lack of an organizing body that led to the decline, but what other factors led to the decline of pedestrianism? Why was it forgotten from American history?

Matthew Algeo: Wow. Well, baseball really … I mentioned that pedestrianism had no commissioner. Well, in 1876, the owners of baseball teams organized the National League and baseball really became the American pastime within 10, 20 years of that. They had a commissioner. They could oversee the sport. They could wipe out gambling. They could maintain the integrity of the sport. Pedestrianism had nothing like that. Also the invention of the bicycle. Remember the old time 19th century bicycles was that kind with the big, huge front wheel …

Brett McKay: Yeah, that hipsters drive around in.

Matthew Algeo: .. and that tiny back …? Exactly. I saw that on Gawker recently. Anyway, yes, the hipsters who drive these big bicycles around, but those are very hard to race. They weren’t very nimble. The invention of the safety bicycle in the 1880s, that’s the bicycle we drive today, with the two same-sized wheels and the drive chain. Well, that was much more interesting to watch race for six days than people walking around a track. So the combination of baseball and the bicycle really eliminated pedestrianism from the sporting scene in the United States. People just stopped watching it. Moved on to other sports, moved onto more interesting things. As for why they’re forgotten, I don’t know. I mean why would you remember people who walked? I don’t know.

Brett McKay: Excuse me, I thought it was interesting, too, towards the end of its heyday, like moral crusaders started going after pedestrianism much in the same way they went after prize fighting or bull fighting or cock fighting.

Matthew Algeo: One of the most entertaining things about watching a six-day race was going into watch day number five or six because the competitors would be so bedraggled. They would be so wore out they’d almost be dead on their feet. That was the exciting thing was to go watch these people after five or six days of continuously walking, what they would look like, how they would behave. So there were morality crusaders, and they were aligned with the temperance movement who came in and said this making fun of these people. It’s like exhibitionism. It’s immoral to watch these people after five or six days. So the weight of this crusade came down on pedestrianism, and it really had a hard time recovering from that.

Brett McKay: We forgot about pedestrianism, but it did lay the groundwork for modern sports as far as its connection to mass media, its connection to gambling, the connection to athletic sponsorships. I’m curious, I think you mentioned the Olympic walking. Is that a remnant of pedestrianism?

Matthew Algeo: It is. Walking is one of the very few sports that has been in the Olympics continuously since the very first Olympics in, what was it, 1896, I forget. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say, pedestrianism really you see it more in even major league baseball or the NFL where the idea of capitalizing on an athletic event. Pedestrianism was one of the first sports to figure out a way to monetize itself. There were sponsorships. There were championships. There all sorts of different ways to make money. That’s all what sports is about today is making money. Pedestrianism was the first sport, I really think … because the other sports were under the radar, boxing and baseball. They were either for gentlemen or for ruffians, but pedestrianism was the first sport that was for the general populous, and they figured out a way to make money.

Brett McKay: I’m curious writing this book, did you start walking more? Because I’m going to try doing one of those feats. Did you start walking more? Because after reading it, I was like, “I’m going to start walking more.”

Matthew Algeo: I encourage you to attend a 24-hour race. I actually did a 24-hour race. People came up to me and said, “Have you ever done this?” “No, no, no, no, no.” Actually last year in October I did a 24-hour race in New Jersey, and I walked it, just walk your 24 hours, see how far you go. I did 51 miles, so I am proud to say that, yes, after all that I was inspired to attempt a 24-hour race.

Brett McKay: There you go. I’m going to have to give that a try. I’m going to do it.

Matthew Algeo: But that’s half, that’s half of what Weston did, or O’Leary did, or Frank Hart did. They would walk 100 miles in a day.

Brett McKay: That’s crazy.

Matthew Algeo: Your basic walking speed is about 4 miles an hour so just go walk but not stop for 24 hours, and you’re not at 100 miles.

Brett McKay: All right. Well, I’m going to give it a try. I’m going to challenge everyone out there who’s listening to go try it this, too. We get some records on here, so we can beat Weston.

Matthew Algeo: It’s really cool. The races are a lot of fun. It’s really cool. The ultramarathons are not for regular people, but 24-hour races, those kinds of races, a regular person can do it because there’s no ‘did not finish.’

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Matthew Algeo: Everybody finishes, so it’s really a lot of fun.

Brett McKay: Very good. Well, Matthew Algeo, thank you so much for your time. This has been an absolute pleasure.

Matthew Algeo: Oh, Brett, I really enjoyed it. Thank you for inviting me.

Brett McKay: Thank you. My guest today was Matthew Algeo. He’s the author of the book “Pedestrianism,” and you can find that on amazon.com. Go get it. It’s a fun, quick little read, and you’re going to find out a bit about American history that a lot of people don’t know about.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this podcast, I’d really appreciate if you would give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher or whatever it is you use to listen to this podcast, or tell a friend about the show. I’d really appreciate that. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.