Every dad wants his children to grow up to be responsible, contributing members of society. But before they head out on their own and make their mark on the world, our kids need to learn how to be responsible, contributing members of the family household. Household chores are training exercises for real life. Chores not only teach children important life skills that will prepare them for living on their own, and impart a pull-your-own-weight work ethic, but recent studies show that starting chores at an early age gives children an enormous leg-up in other areas of their life as well.

Unfortunately, very few children today are getting the training at home they need to become industrious, responsible adults. Studies show that children in the West spend little time helping around the house. While children a century or two ago were expected to do many things to keep the household running, especially if they lived on a farm, according to the Maryland Population Research Center, today’s 6-12 year-old child spends only about 24 minutes a day doing chores. This represents a 25% drop even since 1981. When kids do help around the house, it’s frequently done under duress; parents often have to plead, bribe, and threaten to get their children to do basic things like taking out the trash or cleaning up after dinner.

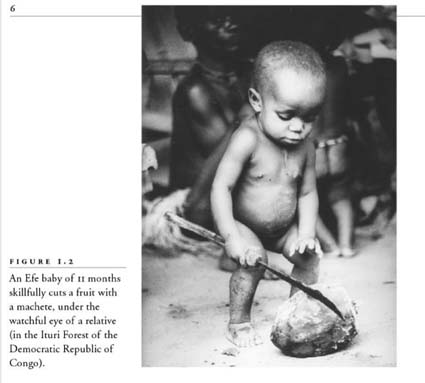

Anthropologists studying child-rearing across cultures have noted that this “chore strike” by children is primarily a Western phenomenon. In developing societies, children are almost universally eager to help out and be useful. For example, in the remote Guarra settlement in Nepal, children as young as 18 months carry firewood and water. Young boys of the Nuer people of Southern Sudan and Western Ethiopia can be found herding sheep and goats without any cajoling from their parents. And infants in a community in Zaire are taught to use even “dangerous” tools like the machete with skill:

A page from The Cultural Nature of Human Development

The contributions of children in developing countries can be crucial to their family’s survival. But doing chores is still important for kids living in the suburbs of America; while their responsibilities may not be central to the livelihood of their households, they are essential in helping them grow up in an unselfish and well-adjusted way and shaping them into fully-functioning adults and contributing members of society.

Last month we ran a series on the basic life skills a young man would need to know as he headed out on his own — they were the things I wish I had learned before leaving home. While it’s never too late to learn those skills, in an ideal world, you would master them as you grew up. So, unsurprising, writing that series got me interested in what I can do now as a dad to help my young son Gus grow into a more competent young man than I was. Below I share some of the benefits of giving your kids chores, as well as what we can do as fathers to get our kids to do the chores we assign them. (Along with some pictures of how we’ve incorporated these ideas in encouraging Gus’ desire to pitch in around the house).

The Benefits of Chores

Gus putting the tops to our Pyrex dishes away in a drawer.

There are two systems that emerge in adolescence that propel young folks into adulthood. One is motivation and emotion — as young adults move into the teen years they seek new rewards and want to branch out, travel, spend time with friends, develop ideals, compete hard in sports, get into good schools — see and do as much as possible. And they feel things very intensely. The other system is control — the prefrontal lobes develop, acting as a check to the newly surging emotions and aiding the adolescent in making good decisions, planning, and delaying gratification. These skills develop through trial and error — through the gaining of life experience.

Human beings have the longest and latest adolescence in the animal world — and spend that time under the watchful guidance of their parents for more than a decade (and these days two). This protected and protracted adolescence allowed the two developmental systems to emerge in tandem: young adults got practice at grown-up responsibilities, but did so under the watchful eye of parents and elders who could assist and guide them when they made mistakes. Professor of Psychology Alison Gopnik explains how the two systems have now gotten out-of-sync and how this has affected the development of young adults:

“In the past, to become a good gatherer or hunter, cook or caregiver, you would actually practice gathering, hunting, cooking and taking care of children all through middle childhood and early adolescence—tuning up just the prefrontal wiring you’d need as an adult. But you’d do all that under expert adult supervision and in the protected world of childhood, where the impact of your inevitable failures would be blunted. When the motivational juice of puberty arrived, you’d be ready to go after the real rewards, in the world outside, with new intensity and exuberance, but you’d also have the skill and control to do it effectively and reasonably safely.

In contemporary life, the relationship between these two systems has changed dramatically. Puberty arrives earlier, and the motivational system kicks in earlier too.

At the same time, contemporary children have very little experience with the kinds of tasks that they’ll have to perform as grown-ups. Children have increasingly little chance to practice even basic skills like cooking and caregiving. Contemporary adolescents and pre-adolescents often don’t do much of anything except go to school. Even the paper route and the baby-sitting job have largely disappeared.

The experience of trying to achieve a real goal in real time in the real world is increasingly delayed, and the growth of the control system depends on just those experiences. The pediatrician and developmental psychologist Ronald Dahl at the University of California, Berkeley, has a good metaphor for the result: Today’s adolescents develop an accelerator a long time before they can steer and brake.

This doesn’t mean that adolescents are stupider than they used to be. In many ways, they are much smarter. An ever longer protected period of immaturity and dependence—a childhood that extends through college—means that young humans can learn more than ever before. There is strong evidence that IQ has increased dramatically as more children spend more time in school, and there is even some evidence that higher IQ is correlated with delayed frontal lobe development.

All that school means that children know more about more different subjects than they ever did in the days of apprenticeships. Becoming a really expert cook doesn’t tell you about the nature of heat or the chemical composition of salt—the sorts of things you learn in school.

But there are different ways of being smart. Knowing physics and chemistry is no help with a soufflé. Wide-ranging, flexible and broad learning, the kind we encourage in high-school and college, may actually be in tension with the ability to develop finely-honed, controlled, focused expertise in a particular skill, the kind of learning that once routinely took place in human societies. For most of our history, children have started their internships when they were seven, not 27.”

I want Gus to be book smart. But I want him to be “street” smart too, and know how to do the laundry, how to clean a house, how to cook — how to function like an independent adult. Chores give children hands-on training in the basic life skills they’ll need to thrive when they head out on their own, while also developing crucial traits like hard work, responsibility, and delayed gratification.

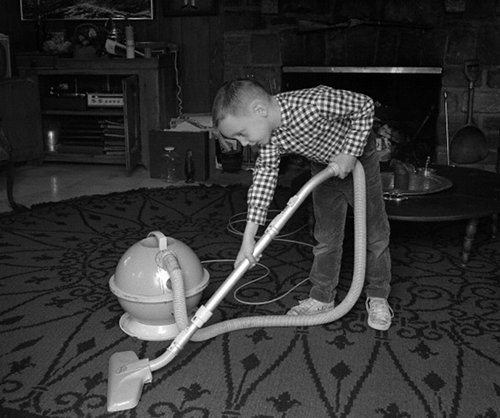

Gus calls the vacuum the “namu.”

In truth, manual tasks and higher learning go hand-in-hand. Doing chores has been shown to develop children’s large and fine motor skills; sorting laundry, sweeping, and digging in the dirt are great ways for children to develop and practice these skills. And this in turn makes them smarter. Studies show that young children who take part in hands-on activities, like chores, develop the parts of the brain that are needed for more abstract thinking like reading, writing, and math.

To sum up: expecting your kids to do chores from an early age helps shape them into self-sufficient, responsible, well-rounded and well-adjusted adults. And studies bear this out. Alice Rossi, a professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst found that doing chores as a child was a major independent predictor of whether that child would do volunteer work as an adult, and research by Marty Rossman, a professor at the University of Minnesota, has shown that one of the best predictors of success as an adult is whether that person started regular household chores at an early age.

How to Get Your Kid to Do Their Chores

Gus helps empty the dishwasher. Careful with that plate Gus!

Start early. The most important thing you can do to help ensure your kids do their chores is to start them as early as possible — ideally when they’re just 18 months old. Psychologists have observed that children naturally want to start helping at around this age. Michael Tomasello notes in his book Why We Cooperate that children as young as 18 months who see an adult having trouble opening a door or picking up a dropped clothespin will immediately lend their little hand in assistance.

I noticed this sudden urge to help in Gus at about that age, too. When I was emptying out the dishwasher one morning, Gus came waddling over and started handing me dishes. He also started helping Kate with the laundry. He’d gather clothes off the floor and put them in the laundry basket and help her put clothes in the washer.

The main thing that squelches this nascent desire to pitch in before it has a chance to fully take root is that kids are unhelpfully helpful. Their “assistance” makes the chore take a lot longer, and they often mess things up, leading parents to just want to do it themselves and quickly get it over with.

Fight the urge to shoo your toddler away when he begins to naturally volunteer to help with chores. Yes, it will take longer to unload your dishwasher, but it’s much easier to instill the chore habit when your kids are young than when they’re surly teenagers. Time invested now will reap rich dividends down the road.

Begin giving your kids age-appropriate chores as soon as you notice them wanting to help and add to that list as they get older and can handle more complex tasks. A lot of parents have very low expectations of what their children can handle chore-wise — but even the littlest kids can really surprise you. Give them new tasks to try, and if they can’t do them, reintroduce them a little ways down the road.

Gus loves to read, but we make sure he puts all his books back when he’s done. Note Gus’ amazing baby mullet; Mom didn’t want to cut his hair for as long as possible, much to Dad’s chagrin. But his glorious rat tail was finally snipped a few weeks ago.

Here’s a good breakdown of age-appropriate chores for your kiddos:

Ages 18 months to 3 years old

- Pick up books and toys

- Put clothes in hamper

- Help unload the dishwasher (take out any sharp utensils first!)

- Help sort and load laundry

- Help put away groceries

- Help clean up spills

- Water flowers

- Put a sock on their hand and let them dust tables and door knobs

Ages 4 to 5

Any of the above chores, and:

- Help make the bed

- Bring things from the car to house

- Help set and clean the table

- Pick weeds

- Help with leaf raking

- Help with simple tasks in meal-preparation

Ages 6 to 7

Any of the above chores, and:

- Make their bed on their own

- Vacuum rooms

- Keep own room clean and tidy

- Empty indoor trash cans

- Put their laundry away

- Sweep garage

- Sort laundry

Ages 8 to 9

Any of the above chores, and:

- Take pet for walk

- Make simple snacks and meals

- Clean the toilet

- Load and unload dishwasher

- Collect garbage and take it to the curb

Ages 10 and older:

Any of the above chores, and:

- Wash car

- Clean kitchen

- Change bedsheets

- Wash windows

- Mow yard (with adult supervision at first)

- Clean shower

- Make a complete meal

Make it routine. Kids thrive on routine. If you want chore-doing to stick when they’re young, make it a routine part of life. Kate and I have been trying to do this with Gus. For example, after Gus eats breakfast, I’ll have Gus take his bowl over to the sink and then we unload the dishwasher together and sweep up any detritus he might have created while eating.

Gus really enjoys cleaning out the lint from the dryer. Next thing I need to do is show him how to use said lint as a fire starter.

Offer praise. It’s easier to get your kids to do something by praising the good things they do than by reprimanding them after they make mistakes. Whenever your tyke makes an effort to help, tell him what a good job he did.

Make it a game. Today’s behavioral scientists are uncovering the power “gamification” has in our lives. Gamification involves using game mechanics in non-game contexts. Researchers have found that turning everyday tasks like exercise, studying, and working into a game-like experience boosts productivity and motivation. You can harness the motivating benefits of gamification with your kids’ chores. There are a few apps on the market that help you turn your kid’s chores list into a fun game with points and level-ups.

Chore Wars is a free role-playing game that allows your kids to earn XP (experience points) and level up their character as they complete chores. You get to control how many points each chore earns. Chore Wars is free.

HighScore House is another free online app that allows you to assign points for each of your kid’s chores. She can then use the points she earns from doing chores to “buy” rewards, like a half hour of television. Parents sometimes do an analog version of this kind of reward system by placing some sort of token into a jar when the kid does her chores. Once the child earns enough tokens, she can “cash” them in for rewards like video game playing time. This system, along with the idea of paying kids for chores, seems quite effective and logical on the surface, but does have some drawbacks, as we’ll discuss next…

One of the many benefits of a push reel mower is that they’re safe enough to let Gus help me push — which he loves to do. Every day when we go to the garage, Gus will head straight to the mower saying, “Push! Push! Push!” even if I mowed just the day before. Because I have to go slow when Gus is “helping” mow, and the push reel mower requires some speed to get the blades spinning, I usually just go over the rows I’ve already mowed when Gus is assisting.

Allowance for chores? There’s a lot of debate as to whether you should or should not give your kids an allowance for completing chores. One of the benefits of giving your children money in exchange for doing chores is that it teaches them the connection between work and money. They learn that if they want something in life, they have to work for it.

But there are some possible downsides of trying to entice chore-completion with money, and they relate to the roots of human motivation. Psychologists break down motivation into two types: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation comes from within — you want to do something because you enjoy it, it interests you, or it’s in line with your values. Extrinsic motivation comes from outside the person — either someone is making you do something, or you’re motivated by a reward like stickers or money. The problem with extrinsic motivation is that the satisfaction gained from a task moves from the task itself to the reward for the task. Thus, if the reward is taken away, the behavior ceases. Studies have shown that once children are offered a reward for an activity, their interest in that activity declines.

Intrinsic motivation leads to a greater sense of well-being and is fed by the fulfillment of 3 needs:

- Competence. Sense that you can control the outcome of something and the feeling of mastery.

- Relatedness. The desire to interact, connect with, and care for others.

- Autonomy. The feeling of being the director of your own actions.

Paying kids money to do chores does not meet these needs nearly as well as expecting them to do chores simply because they are part of the family and need to be a contributing member of it. Kids will experience the reward as an external form of control, and as something that doesn’t have anything to do with membership in the family. And what happens if they decide the money offered isn’t worth it or Grandma slips them $100 for their birthday, and they don’t feel they need their chore allowance? Then the parent has to try to force them to do something for free they didn’t want to do for cash, creating a power struggle, and making the child feel decidedly un-autonomous. Perhaps most worrisome, offering money for doing chores can also create the sense in children that everything they do should be rewarded. This sense of entitlement can hinder their development later, when they discover that they must fulfill many adult responsibilities that don’t offer any immediate reward and simply have to be done to function independently. It can even stymy their interest in hobbies done solely for pleasure — kids taught to always look for an external reward may not see the point.

The better approach, at least in my opinion, is to expect kids to do chores from an early age simply because that’s what’s expected of them as members of the family; mom and dad don’t get paid for their chores, so neither do they. This will build their competence and relatedness and thus intrinsic motivation from an early age. But you still want to teach your kids about managing their money, so each week they get an allowance not tied to chores. With guidance from mom and dad, they’re allowed to spend and budget it as they’d like. If they want to buy something out of reach of their weekly allowance, they can save and budget, or they can talk to you and the Mrs. about doing extra jobs — chores outside the scope of their expected chores — for extra pay. With this system you still help them experience the connection between hard work and getting what they want, while boosting their autonomy and their competence in managing their money.

What are your tips for getting kids to do chores? Share them with us in the comments!