Last year, 25 people were killed by avalanches in the United States. The number may not sound like much, but that’s 23 more than were killed by sharks last year, and 25 more than have ever been killed by a Yeti.

The victims are typically backcountry recreationalists—skiers, snowboarders, climbers, and snowmobilers. Snowmobilers account for twice as many avalanche fatalities as the other groups, mostly because of their surging numbers, and also because the weight of the snowmobile and rider is greater than that of a person on skis, making them more likely to stress the weak layer in a snowpack and set off an avalanche (the noise isn’t the reason, by the way. The idea that noise can cause an avalanche is a myth). Avalanche victims are often risk takers that set aside safety concerns in the pursuit of their goals, and 89% of them are men.

While the majority of avalanches happen naturally, 90% of avalanche fatalities occur in avalanches triggered by the victim himself, or by someone in the victim’s party. So avalanches aren’t exactly freak accidents, and there is a lot you can do to avoid getting swept up in one and to increase your chances of survival if you do.

Now here in Oklahoma, the avalanche threat hovers right around zero percent. So I called up Sarah Carpenter, an instructor at the American Avalanche Institute in Victor, Idaho to fill me in on how to prepare for, survive, and help a buddy out of an avalanche.

Preparation

Of course the best way to survive an avalanche is to avoid getting into one in the first place! How do you do that?

Education

Avalanches will never be 100% avoidable, but understanding and watching for the elements that make avalanches more likely to occur can significantly reduce your risk of becoming a victim of one.

The factors that increase (or diminish) the likelihood of an avalanche occurring are surprisingly complex—things like weather, sun, temperature, wind, the angle of the mountain’s slope, and snowpack conditions all play a role. And the avalanche hazard level can fluctuate daily and even hourly as conditions change.

Thus, the ability to scout for potential avalanches takes a goodly amount of both know-how and skill. You should be able to do things like measure the angle of the slope and test the stability of the snowpack, in addition to being trained in how to search for a buried victim using a transceiver.

In order to learn this life-saving knowledge and skill set, it is highly recommended that you take an avalanche safety and survival course. And I’m not just saying this because Sarah was so nice and helpful with me! Talk to any mountain or ski guide and you’ll hear the same thing: if you’re going to be heading out into the backcountry, you need to take an avalanche course.

Avalanche professionals make up less than 1% of avalanche fatalities, and the closer you can get to thinking like a professional, the better.

Equipment

In addition to your knowledge and skills, you also need to carry a few key pieces of equipment into the backcountry with you.

Transceiver. Sometimes referred to as a beacon, a transceiver is a radio that both transmits and receives electromagnetic signals. If you’re buried by an avalanche, the signal from your transceiver will allow your partner to find you. But obviously you both must be wearing one, and you need to set your transceiver to transmit when you head out. People have died because they got buried with their transceiver set to receive. Using a transceiver takes skill, so you want to practice with it before your backcountry adventure.

Avalanche probes. Using a transceiver will get you close to the victim, but a probe will allow you to pinpoint him in the snow. The best kind to get are collapsible probes that you put in your pack and assemble like a tent pole. Ski poles that can be screwed together to form a probe are also available. If you lose your probe in the avalanche, try using a long tree branch–it’s better than nothing.

Shovel. Digging with a shovel is almost 5 times faster than digging with your hands, and as we’ll discuss below, the speed with which you can dig is absolutely critical in saving the life of an avalanche victim.

What to Do If You’re Caught in an Avalanche

Sarah says that “If you’re caught in an avalanche, the best thing you can do is try to get out of the avalanche!” Sound advice. How do you do that?

When the Avalanche Starts

If the avalanche starts right under your feet, try running uphill or to the side to get off the fracturing slab of snow. If you’re on skis or a snowboard, head downhill first to gather some speed, and then veer to the side and off the slab. If you’re on a snowmobile, continue in the direction you were going and throttle it off the sliding snow.

If you’re not going to make it out, drop your ski poles, pack, and equipment, and abandon your snowmobile—you want to be as light and buoyant as possible in order to minimize how much you sink into the snow.

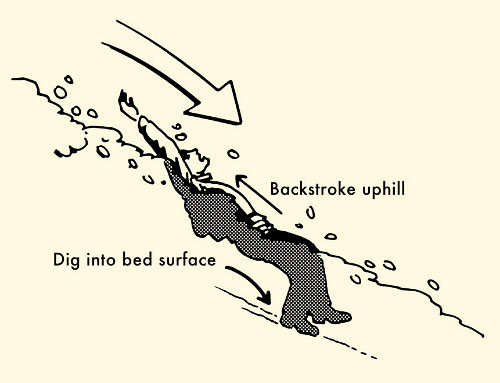

Once the snow topples you, “swim” to try to stay on top of the snow. You may have heard that you should swim like you’re bodysurfing a wave, but that will actually take you towards the “toe” of the avalanche (the tip of the avalanche debris) which is the most turbulent zone of the avalanche—not a place you want to be. Instead, you want to roll to your back with your feet pointed downhill. Do the backstroke and try to head uphill. You can also try to dig into the bed surface–the layer the avalanche is sliding on–with your feet in order to slow your descent.

You may have also heard that you should try to crouch behind rocks or trees, but this is a bad idea. Trees and rocks slow snow down, causing it to pile up in that area. Hiding behind a rock will just bury you deeper in the snow.

If you can grab onto a tree, do it. But being able to do so is easier said than done. “Grabbing onto a tree is a lot less likely than it sounds, as avalanches move at a high speed,” says Sarah. “Grabbing trees is possible when the avalanche is first triggered. It is much less likely as the avalanche gains momentum.” Indeed, avalanches can move at 60-80 mph!

Once the Avalanche Has Buried You

If the avalanche buries you, and you’re still alive, consider yourself lucky. About 1/3 of avalanche victims are killed by trauma; the avalanche can carry you into a tree or over a cliff and the debris it picks up as it storms down the mountain can clobber you.

Once the avalanche stops moving, it will begin to set around you like concrete. So your window for taking any kind of action is very small.

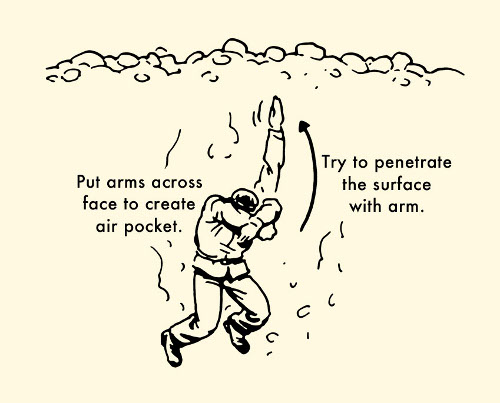

Immediately create an air pocket by putting your arm across your face—this gives you a little room to breathe. As the snow begins to set up, take a big breath. This expands your chest, which can give you a little extra breathing room as the snow hardens around you. If you’re near the surface, try to reach an arm or leg up to penetrate it; this will obviously make finding you a lot easier.

But which way is the surface? You may have heard about the trick where you spit in order to see which way is up. But you’ll likely be so entombed that this will be very difficult to do, and knowing the direction of the surface won’t help you anyway; unless you’re very near the surface, once the snow sets it’s going to be impossible to dig yourself out.

The big thing is to stay as calm as possible, which Sarah admits is “easier said than done.” But the calmer you are, the slower you’ll breathe and the less quickly you’ll use up the oxygen. Don’t yell either—the snow is so insulating that rescuers are unlikely to hear you.

Now you just have to wait for your buddy to rescue you. Hopefully, he’s prepared.

What to Do if Your Partner Gets Buried by an Avalanche

If you see an avalanche sliding towards your friend, do your best to keep your eyes on him and track where he ends up. Once the avalanche stops, be sure the danger is over, and immediately begin to search for him.

Don’t go for help. It might sound counterintuitive, but one of the worst things you can do for your buddy is hike to a rescue station for help. To survive an avalanche, time is of the essence. There are different sets of data on survival rates, but generally speaking, the best chance of survival is within the first 15 minutes of getting buried; if the victim hasn’t been killed by trauma, he has about a 90% chance of making it if he’s rescued during that window. At 30 minutes, his chances of surviving drop to 45%.

So again, it’s essential to begin your rescue efforts right away.

If you weren’t wearing transceivers, Sarah recommends looking “for clues on the surface–skis/poles/hat/gloves.” “Oftentimes,” she told me, “people are buried in line with these surface clues. There are also likely burial spots that should be searched with a probe–above rocks and trees, on the outside of the avalanche path if it curves, on benches. These are areas where people tend to be buried, based on the dynamics of moving snow.”

How to Dig for an Avalanche Victim

When you picture yourself trying to rescue your friend from an avalanche, chances are you imagine frantically looking for where he is buried. But locating a victim with a transceiver and probe is the easy part; it’s the digging that takes the longest. In uncovering an avalanche victim, you’re going to have to move 1-2 tons of snow—that’s no easy task.

Thus, understanding how to dig efficiently and effectively is one of the most important keys of avalanche victim rescue.

If the victim is buried under a meter or less of snow, just start digging like a mad man. But if they’re buried in snow that’s over a meter deep, you should employ one of two different digging strategies, depending on how many people you have with you.

If you have a big group of available diggers, use the “V-shaped conveyer belt” method. The rescuers line up like a flock of geese in a “V.” The front person does the digging, and moves the displaced snow just a little ways behind him. The two people behind the digger then push the snow to the people behind them, and on down the line. The front person is rotated every minute or so, so that the digger remains fresh.

If it’s just you and the buried victim, you’ll want to employ the “strategic digging” method.

When you locate someone with a probe and know exactly where they are in the snow, you don’t want to dig straight down into where the probe is sticking out of the snow. The probe might be at their legs, and when you dig down, you may shovel snow behind you and onto their air pocket, collapsing it. And you’ll end up with a cone-shaped hole that’s not at their airway.

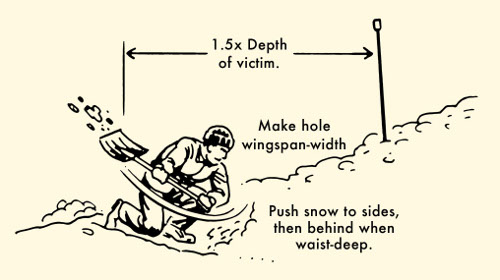

Instead, shift downhill from the probe, about 1.5 times the length of the depth the victim is buried, and start digging into the side of the slope, straight into the buried person. To save more time and energy, shovel the snow out to the side instead of behind you, until the snow rises to your waist—then start moving it downhill. Uncover their face and clear an airway as soon as you can.

If there are two available shovelers, position one just downhill of the probe, and the other downhill 1.5 times the depth of the buried victim. You should both start digging the hole, moving the snow to the side. When you have to lift the snow above your waist, start shoveling it downhill—the digger furthest downhill works on keeping the hole clear as the front digger keeps shoveling into the victim.

Another advantage of strategic digging is that you can create a platform onto which you can pull out and then work on the victim. From this position, it will be easier to clear their airway, perform CPR, and administer first aid, if needs be.

Backstroke uphill

Dig into bed surface

Put arms across face to create air pocket.

Try to penetrate the surface with arm.

Make hole wingspan-width

Push snow to sides then behind when waist-deep.

___________________________________________

A big thanks to Sarah Carpenter for her patience in answering my many, many questions for this article! If you’re looking to take an avalanche course, be sure to check out the American Avalanche Institute. For more than 35 years their seasoned experts have been teaching recreationalists and professionals alike with hands-on courses that are at least 60% field-based.

Additional Sources:

Forest Service National Avalanche Center

National Snow and Ice Data Center: Avalanche Awareness

Strategic Shoveling with Backcountry Access

Like this illustrated guide? Then you’re going to love our book The Illustrated Art of Manliness! Pick up a copy on Amazon.