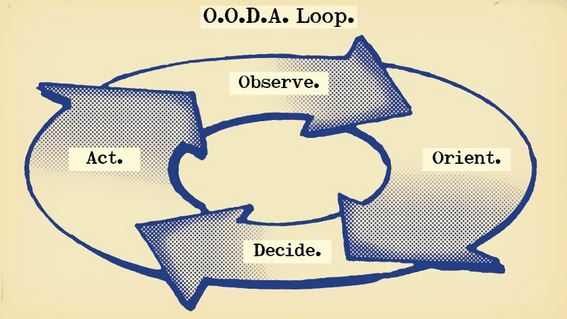

The OODA Loop — the OODA stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act — is a strategic tool designed to help people make better decisions when facing any kind of competitor or opponent.

My guest today says that when that opponent is a seasoned criminal, the Orient component of OODA — a person’s mindset — is the most underestimated and critical part of the model to understand.

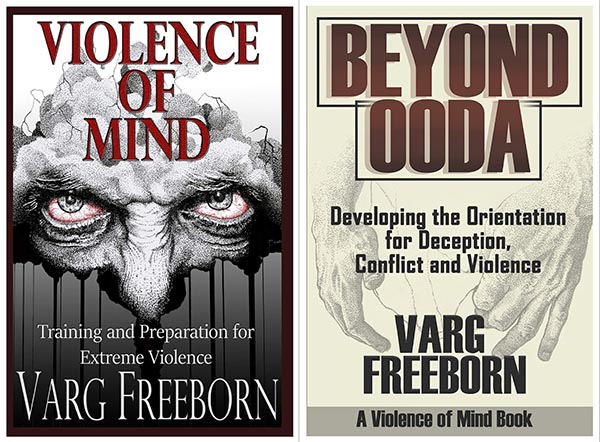

His name is Varg Freeborn and he’s the author of Violence of Mind: Training and Preparation for Extreme Violence, and Beyond OODA: Developing the Orientation for Deception, Conflict, and Violence. We begin with how Varg’s life story has uniquely positioned him to understand the dynamics of violence from the perspectives of both the perpetrators of crime, and the would-be preventers of that crime. Varg shares how he went from being a convicted felon to a self-defense and firearms instructor who’s worked with both civilians and law enforcement.

We then turn to why it’s so important to understand the difference between the orientation of an average person and the orientation of a violent criminal, and why, when the two collide, the latter has a real advantage over the former. We end our conversation with what you can do in terms of mindset and training to close that gap, and be better prepared to handle a violent encounter.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- AoM article on the OODA Loop

- AoM Podcast #198: Turning Yourself Into a Human Weapon

- AoM Podcast #334: When Violence Is the Answer

- AoM Podcast #688: Protection for and From Humanity

- AoM Podcast #513: Be Your Own Bodyguard

Connect With Varg Freeborn

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript!

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. The OODA loop, the OODA stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. It’s a strategic tool designed to help people make better decisions when facing any kind of competitor or opponent. My guest today says that opponent is a season criminal. The Orient component of OODA, a person’s mindset is the most underestimated and critical part of the model to understand. His name is Varg Freeborn, and he’s the author of Violence of Mind: Training in Preparation for Extreme Violence and Beyond OODA: Developing the Orientation for Deception, Conflict, Violence. We begin with how Varg’s life story has uniquely positioned him to understand the dynamics and violence from the perspectives of both perpetrators of crime and the would-be preventers of that crime. Varg shares how he went from being a convicted felon to a self-defense and firearms instructor who’s worked with the civilians and law enforcement. We then turn to why it’s so important to understand the difference between the orientation of an average person and the orientation of a violent criminal and why when the two collide, the latter has a real advantage over the former. We enter into a conversation with what you can do in terms of mindset and training to close that gap and be better prepared to handle a violent encounter. After the show is over, check at our show notes at aom.is/orientation. Varg joins me now via clearcast.io.

Varg Freeborn, welcome to the show.

Varg Freeborn: Hi, thanks for having me on.

Brett McKay: So you are a strength coach, and you’re also a firearms and self-defense instructor who trains both civilians and law enforcement. And you’ve got two books out that are really good, you got Violence of Mind and then Beyond OODA Loop, and I hope we can discuss some of your ideas there. Before we do, I think it would be helpful to talk about your background because you got to your career as a strength coach, as a self-defense instructor, a firearms instructor differently than a lot of other firearms instructors, and I think it’ll help… Understanding your background will help readers understand your approach to self-defense and violence. So, what was your upbringing like? Tell us a story.

Varg Freeborn: I grew up very, very rough. I was basically raised up in a dope house, and my mother was 16 when she had me, so a single teenage mom. She had probably seven or eight brothers and sisters, and they were all drug addicts, alcoholics, gang members, drug dealers. So the house I grew up in was very violent, I experienced very violent things at a very early age. Nearly became the victim of a stabbing when I was seven, someone was loose in the house and stabbing my family members and came after us and my mother and aunt were able to get us barricaded in my grandfather’s bedroom with a tool box, and basically the attacker was stabbing through the hollow core door. That was a very memorable moment for me as a young kid. I was, again, like seven years old, so it’s pretty dramatic. That was an example of that… Things like that happened quite often. Had a cousin murdered, best friend was murdered, one of my uncles was murdered. So it was a pretty rough upbringing.

Brett McKay: And so from a very young age, you saw violence firsthand, you experienced it. And I think at one point, your mother re-married and your step-father, very violent, strangled you and I think you took a baseball bat to his head and he stopped messing with you after that. So your teenage years, same thing, continue on. Just getting more intense. And then there’s this moment, you ended up in prison. What’s the story there?

Varg Freeborn: Yeah, so I was 17 and obviously there was a catalyst for this event, and the beginning of it was a relationship with a girl. And so, out of that came a guy that was angry with me over who I had dated, and he just pushed this thing over and it went on for six, seven months. He was much older than me, outweighed me by about 100 pounds, and he relentlessly pursued me for about six months. And I really tried to avoid him, I was trying to kinda get my life on track and pursue things that I wanted to do and get away from the nonsense that the beginning of my life had been marked up by. So I was trying to avoid this situation as much as I could, unfortunately, I wasn’t able to, and one night he found me at a house party, and this was like 1:00 in the morning, and he had two his friends with him, and he was incredibly drunk and high, just really out of his mind, intoxicated. And he initially had tried to get me to leave with him and his buddies, and it was one of those things where someone’s incredibly drunk and they think they’re making sense, but they’re not making any sense at all, and that’s kind of what it was like.

He really thought that maybe he could convince me that we were friends and that I could leave with him safely. As I said, this was a time when my best friend was shot in the head and thrown in a lake, one of my cousins was murdered, so when someone like this guy had been… Is telling you that they’re gonna kill you, it’s something that you take serious back then. In that environment, that day and time, it was something that you would take serious, so I didn’t take it lightly when he said that. And that night basically, he ended up cornering me, and I told him a bunch of times, I was even to the point of witness coaching by this point where I’m saying things for people to hear it because I know something bad’s gonna happen and I’m trying to at least lay the ground work that I’m trying to avoid this situation, I want people to remember that. Of course, they didn’t.

But he comes and corners me in a back room, and I see that his friends had went outside and pulled the car back to the back door, which is where the back room was also. So I’m thinking to myself, this is about to go really bad. Because if these three guys that outweigh me and outnumber me get a hold of me and put me in that car, who knows what’s gonna happen next. So I just made my mind up that I wasn’t going into the car, and he reached up and I told him several, several times, “Leave me alone, don’t touch me.” And of course, he was just persistent in doing what he thought he was gonna do. So when he reached for me, he grabbed me and began to choke me, and that’s when I pulled a blade and I went to work on him and I stabbed him a couple dozen times and he didn’t draw up until the last one. So it was very eye-opening to the resilience of the human body and how much it takes to actually stop someone who’s determined, whether they’re intoxicated or not. And during that situation, he had a lacerated internal artery in his neck, lacerated jugular and a collapsed lung and he was in pneumothorax, and he still survived.

However that comes out, he survived those injuries, and then when we went to court, he wasn’t the tough gangster anymore that was gonna kill me, he was the afflicted victim of a vicious attack and on and on, and this type of thing was just… It was the most unbelievable thing I’ve ever experienced in my life, to see how the story shift and all of a sudden you become a villain in a way that’s like, it’s getting ready to take your life away. And so I ended up being convicted, and I started out with an attempted aggravated murder charge, which was 25 years, and I was able to plea that down with some help from some family members who scraped together some money, and I was able to play that down to a two to five year sentence, and I ended up serving the entire five, probably due to be in such a model prisoner. But yeah. So that was basically how that went down.

Brett McKay: And then when you were in prison, you continued to see violence firsthand. What was prison life like?

Varg Freeborn: Oh, for sure. Now, this is something that… And I don’t claim to be hardcore or be an expert on anything, and I don’t claim to be an amazing fighter or anything like that. But I can tell you that I was in prison during one of the most violent times to be in prison, because if you look at the violent crime statistics and the murder rates, which it’s going back up now for reasons that’ll be another discussion. But before 2020, violence was way down and used to be able to say, “Well, the murder rate is down 50%.” And it was true, because if you look back to between ’85 and ’95, the violent crime and murder was up to 50% higher during that time. Well, by the early ’90s, and ’94 was when I got convicted and locked up, most of those people had been locked up, the ones that weren’t dead. So it was a time where you had the most violent street criminals in the longest time that we had seen for a while and they were all locked up and the prisons were overflowing.

And so when I first got there, it was so overflowed that we ended up being put in a gymnasium that was converted to a bunk room that had probably 400 bunks in it, so you got 600 to 800 people shoved in this gymnasium that was a basketball court, and this is an intake prison. So an intake prison is… They bring in everyone to this initial facility and decide where you’re going to go as a parent facility from there, and they’ll ship you to wherever in the state they want to. And so, the problem with an intake facility is that you’re in there with everyone. You’re not… If you’re minimum security, your’re bunking with a maximum security guy. I remember I had one cellmate that had murdered five prostitutes with a claw hammer, and so you have to go to sleep at night with these people. And this is the type of thing that was your introduction to prison, like 19 years old and I’m like 135 pounds. And I was a pretty violent kid, for sure. But this was like the big leagues, so your introduction is a paradigm shifting experience, for sure.

Brett McKay: I wanna talk more, maybe there’s some insights we can take that you’ve learned about violence from your experience in prison, and we can talk about that later. But you serve your time, you do five and you get out, you’re a felon. And mostly, when you’re a felon you can’t vote, you can’t have a gun, you can’t work at a government job, etcetera. But you were able to do all those things. What happened there?

Varg Freeborn: Well, I was fortunate enough to have been locked up in Ohio. So Ohio has an automatic restoration of the right to vote, the right to sit on a jury and to right to hold public office when you’re released from prison. The thing that they don’t have is an automatic restoration of firearms rights, and that’s obvious. Most states, you can’t even get it back, but Ohio did have a restoration process. I had continued to fight my case while I was in prison, and I continued to fight my case when I got out of prison because I always believed that I acted in self-defence and I had no choice. And basically what happened after I got out is I finally got them to sit down with me and they said, “Look, we’re not gonna open this case up, because if you cause us to open his case up again, we’re gonna take you right back to the original 25 years and we’re gonna disregard the five that you served.” Which is a tactic that the state will use any time they don’t wanna do something.

So what they did do is they said, “We will give you a restoration of your rights and give you all of your rights back.” And so, I thought, Okay, that’s a pretty good deal. So they gave me a restoration of all of my rights to vote, sit on a jury, hold a public office and own and possess firearms as allowed by state and federal law. And then they issued me a concealed carry license, but they never removed the felony, so I have a very unique situation of being a felon that also is allowed to carry a gun. The felony was never expunged, it was never removed from my record. And if you pull up my record, I get pulled over, they pull it up, they’re going to see the felony and they’re going to see the restoration, and then they’ll see the concealed carry license. So it’s a very interesting thing, but I was able to fight that enough to get at least that back and that took quite a few years for that to happen, for sure.

Brett McKay: So you got your rights restored and now you are an instructor, you teach police officers and military guys about self-defense and firearms, right?

Varg Freeborn: I do. I am semi-retired from the active training part of it here in the recent time since COVID, actually, that kind of pushed me into a slow down for sure, and then I just never kicked it back up because I just never intended on retiring in that business anyway. And so, it was a good time to kind of semi retire. But I still work with… I’ll be at Ohio Tactical Officers Conference this year, and I’ll be at maybe one other conference and it’ll be working with civilians and law enforcement and military guys. And I do like to train, I do like to teach. And the way that I accomplished that was after I had gotten my restoration, I started to see the boom that was happening in self-defense training. And one thing that I seen was this huge gap in information between reality and what was being taught in the mainstream of that industry. And so, all that I wanted to do was fill some gaps in for people and say, “Hey, based on my very real experience, this is not how that typically goes, and you’re going to need to prioritize things differently than what you’re being taught here.”

And I was pretty early on, grabbed by law enforcement guys and pulled into the law enforcement training world. I was sent through a lot of closed enrollment training on the LE side. So I’ve been to breaching school, ballistic, thermal, mechanical, explosive breaching, I’ve been to just hundreds and hundreds of hours of CQB training from different angles and different disciplines and different agencies. I was certified all the way up to a full team CQB instructor, which I will never do, but it added to my knowledge base for their benefit as well as mine. And I’ve done law enforcement executive protection training and just on and on to the things that I got fortunate enough to get pulled into, so I was able to train at a very high level on that side of the fence after having a very real experience on the other side of the fence with violence. I’ve been involved in multiple stabbings, I was involved in stabbings in prison. I’ve been stabbed multiple times, myself, I have at least one body part missing from the stabbing. And so, this was something that really rounded out my experience and my perspective. To be able to see these things from both sides of the door, basically.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Let’s talk about, how does your personal experience with violence change the way you approach or think about training people in self-defense? I mean, what are you… Like you said, there’s gaps. What gaps do you see in traditional self-defense training that your experience can fill it? What’s the difference between the way you approach it and most other self-defense instructors approach training?

Varg Freeborn: I think that it didn’t change anything for me, it was more cultivated from a very young age, so I didn’t have a change moment for myself. But what I do see in the difference between myself and what’s taught by most of the instructors, especially when I started this business, is the prioritization of decision-making and the components that go into decision-making over weapons and techniques and things like that. So I think that your least experienced instructors will always be weapons-focused, technique-focused, speed-focused, always thinking about those types of things. And your more experienced instructors tend to be more decision-making focused and cultivating the ability to make good decisions when faced with very dire consequences and fast moving situations. So I think that’s probably the biggest marker between the two that I see.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I’ve noticed in my own experience, I’ve taken firearms training, you go and it’s just… You’re just kind of doing like a choreo… Like a kata, almost. Just like, “Here you can do this draw and then you’re gonna take a step… ” And I mean, it was fun. But after the experience, I don’t know if this is actually gonna be useful in a real life situation.

Varg Freeborn: Yeah, it’s kinda like, if we remember the times of the McDojo age, in the late ’70s into the ’80s when everybody wanted to learn karate, because Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris were the main things on the big screen and everybody wanted to do that. And then, when reality hit that whole movement in the face with MMA, and you don’t see Karate and Kimpel black belts dominating anything anywhere in any ring, that was like a wake-up call for that. And I think the firearms industry has had that coming and is experiencing it now to a certain extent, but when you have guys coming back from… And not necessarily like 11B’s or something, but special operations. Guys that have been in very heavy situations, heavy fights with very small numbers, very up close and personal, you’ll see more and more the decision-making process is almost all that they will focus on. The weapon skills are very professional to a standard, and that’s it. Like you just… Here’s your standard, work until you can achieve the standard and then work to maintain it, and that’s the simplicity of the weapons part of it. The rest of it is all being able to make the decision, being able to see the situation for what it is.

Analyze the information, synthesize it with what you already know, and then move forward with good decisions that’ll keep you and your people safe, and that’s the difference that I see that… That you really need to focus on if you’re going to really think about getting into a fight. Like you say, the kata… Is it gonna help you? It might. It might because it may be there when you need it and you’ll do this perfect move, and it was the thing you needed at the time, but the likelihood of those circumstances lining up like that is very low.

Brett McKay: Okay, so let’s shift gears to your book. So there’s Violence of Mind, and your most recent one is Beyond OODA. And OODA loop was developed by a guy named John Boyd, military strategist. It is a decision-making model, and you hear it used a lot in the tactical self-defense world. But you have a different emphasis that a lot of guys miss so I wanna talk about that, but before that, for those who aren’t familiar with OODA loop, can you give us a big picture overview of what it is and how it’s used in the tactical world?

Varg Freeborn: Yes, so John Boyd, who retired a full colonel from the Air Force, was the developer of OODA loop, and it’s not really a loop, and it really grew and developed beyond that first conception that he had as an OODA loop, which was very much like… Observe, Orient, Decide, Act, which is what the acronym stands for, and it became a very complex series of loops, and there’s bypasses and there’s different mechanisms within this process that change how a person makes decisions, how quickly they make decisions, and how quickly they can act on it. And so, I’ve never been a big OODA loop guy, I’ve never used OODA in my training, I’ve never used it as a model in the lectures I do or any of the classes that I’ve taught, but I do focus on the orientation part, and one of the things that I think people miss the most about the Observe Orient Decide Act concept is there were many, many…

There was 30 years of development that went into that with Boyd, and for most of that time, Chet Richards and Chuck Spinney were working very closely with him, so there were actually three people involved in the development of that concept. Boyd gets full credit because it was his idea, and he was the main driver, but it couldn’t have been what it became without the other two guys helping him and being very close friends with him. And as the stories go, they would get these crazy phone calls from Boyd at 2:00 AM and he’d have this breakthrough idea and they’d have to get out of bed and listen to, is this the type of person that Boyd was.

And without those guys there, this would have never became what it did, and some guys will get stuck on the simple loop that it began as and think that’s what it is, and I’ve even heard it so incorrectly put us to say that orienting was physically facing yourself towards the threat, which couldn’t be more farther from what it really is. And I think that the other guys will consider themselves guru of the concept, but they’ll point towards things like the Aerial Attack Study, which was Boyd’s work in the ’60s and completely disregard what he did in the next 30 years of his work life. So what I think that is most important to understand about OODA is basically your orientation is what drives your decision-making and your actions, and your orientation is made, as he put it, a repository of your genetics, your cultural inputs, your value systems, your experiences, your confidence, all of those things are what actually drive and influence your decision-making process, and I think that’s really, for me, the most key takeaway from OODA that you can have.

Brett McKay: Yeah, even Boyd said, orientation was the most important part, is that orientation is based, this is the kind of way I summarize, your mental models of how you see the world or perceive the world, and again, like you said, like Boyd says, your genetics, your culture, your upbringing, your personal experience with violence, all color how you see the world, so orientation will influence how you observe. Right?

Varg Freeborn: Yes.

Brett McKay: And then orientation will also determine how you’d make a decision, and orientation will also determine how you’re going to act. So I think like you said, I’ve read a lot of articles and I’ve heard… I’ve gone to the gun range and had some guy tell me about OODA loop, they just kind of glance over orientation. They just focus on the observe part and then decide and act, but then if you look into it, like you guys did it, like orientation, that is everything. I’d be better just to focus on that when you think about the OODA loop.

Varg Freeborn: Yes, yes. And actually, of the two guys that worked with Boyd, Chet Richards and Chuck Spinney, I actually was able to develop somewhat of a relationship with Chet Richards during the writing of this book, and he obviously wrote a review for the book, and he also really advised me on the first part of the book where I’m talking about the OODA loop so this is not something I just flew by the seat of my pants. I took this to the source and I was like, “Hey, here’s my perspective. What do you think?” And I had no idea what would… I didn’t know if he’d come back and say, “You’re a full of shit guy and you’re way off base.” And so I threw this at him and he came back and was super excited about it, and he said, you know, this is exactly… He’s like, “You’ve got Boyd figured out here.”

He said this is exactly what Boyd would get excited about and would wanna talk about and would wanna work on when he was still alive. And he said this is a very important book, and I felt great about that when he said that, and I said, okay. And then he even took the time to dig into personal letters that Boyd wrote him and gave me access to quote some of those and things like that, stuff that people have never even seen. So it was a very cool experience, but the validation encoded in that was extremely powerful, and with the orientation part of it being the central… Obviously, the central focus on the book, and orientation also being the central focus of a lot of Boyd’s work, especially in his last 15 to 20 years, I think that we can safely say that if you focus on the orientation components, that is what drives decision making.

Now, can a person’s culture be changed? Yes, but it’s not an easy thing to do. And at some level, it requires what might even resemble brainwashing, where… And the military does a good job of this sometimes, where they take young men and completely change their culture to one of brotherhood and camaraderie, and you’ll fall for the guy next to you and all this type of thing, and that’s what they send them effectively into war with, is that new culture, this new paradigm, this new system of values that they’ve instilled in them. And if they genetically receive that, that’s great. The problem that I see with it is the big difference between the good guy and the bad guy. There’s an initiation process that happens in an orientation to violence, and it’s gonna be probably your first big event, you’re first killing, your first lethal force level event that is going to initiate you into the experience.

And for someone who’s been prepared for that or someone who seeks that initiation, then it’s a very different experience than for someone who does not seek the initiation and gets it. And I think that there’s such a violent shift in their mind, and psychologically, their paradigm has shifted so quickly and so violently that there’s moral injury and other things that cause severe PTSD to happen after a violent shift like that. And I’m no expert, but from my own experiences and from talking to several of my friends who’ve experienced war first-hand, these are conclusions I come to, and I think that the initiation process with the orientation is probably the most important thing to look at and try to simulate or try to achieve at that point.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I wanna dig more on that initiation process and how it can shape orientation, but before we do, let’s talk about this. One of the things that Boyd talked about so generally with the OODA loop, is if you wanna beat the other guy. So in any competition, he’s basically saying there’s a OODA loop going on in every competitor, right? If you’re the guy defending yourself, you have a OODA loop going on, and then the guy who’s trying to do something to you has an OODA loop going on, and whoever can cycle through their OODA loop first is gonna win, but how fast that OODA loop goes depends on things like orientation, for example…

And you argue that if you really wanna make better decisions when it comes to self-defense, you need to understand the orientation of the person who’s attacking you. And I think a lot of people who are just sort of regular dudes who grew up in the suburbs, they don’t really understand the mind or the orientation of a criminal. You’ve been in prison, where you’ve seen criminal life firsthand, what’s their orientation? What is the orientation of a violent criminal and what’s contributed to that orientation?

Varg Freeborn: So we can’t speak just generally about every criminal, because just like every other profession or sub-culture, there’s the whole spectrum of human beings and they’re from idiots to experts, but I think that the biggest difference when we’re talking about serious violent criminals that are going to do very high levels of damage or become lethal, that… Again, we go back to experience, confidence, and initiation. The thing that’s going to be lacked the most in the good guy group, whether it’s law enforcement or civilian and self-defense, is initiation experience and confidence that comes from both of those things. Now, when a criminal… Let’s say, for example, when you look at a young gang-banger who grew up very rough, didn’t have anybody who really cared about them, had a really rough way to go, was treated like trash at school and by the establishment and looked at very suspiciously if they went anywhere and just was just rejected by the world, now, I’m not condoning or anything like that, I’m just saying, this is their experience, this is their paradigm, this is what they see around them.

And so they become angry, they become violent. Violent tendencies begin to grow, and then they glorify that lifestyle, and then they wanna think about bucking somebody in the chest and putting their enemies down like dogs and being a soldier and things of this nature start to become important to them. They start to prioritize that very highly. At this point, it’s still a story that they’re telling himself about who they are, and they may be like, “Yeah, yeah, I’ll buck somebody to the ground,” and they’re telling themselves this, but they haven’t acted it out yet.

Now, the second that they act that out, there’s going to be a very dramatic paradigm shift that happens inside of their brain, and they’re going to become a part of the story they’ve been telling themselves, a part of the story that they’ve been glorifying. So if they come home, they’ve got Tony Montana on their wall and they wanna be a big time dope dealer and have the cars and the women, and the pitbulls and all this stuff, so they start to live that story. They start to make that story real, and so when the story becomes real, the confidence level goes way up, because now, they’ve actually done the thing that they said they were going to do. They’ve experienced it, they’ve proven it to the world, they’ve run it to themselves, and there’s no questions anymore. It’s a very real thing, and it’s known. It’s not an unknown.

And so the difference is for the good guy, so the so-called good guy, doesn’t have that initial sociopathic tendency towards violence that glorifies it, and the initiation is gonna be a very different experience when he gets it. And if he’s not properly prepared for it, then when it happens, it’s gonna be a violent shift that might tear his psychological world apart. And then there’s gonna be that whole thing to deal with, and we see this when we see aftermath videos of officer-involved shootings, where the officer just break down and just uncontrollably go into trembling, crying and things like that, and it’s male and female both.

It’s not just one, and we’ve seen this, it’s not a lot, but there are times where we have had the opportunity to watch that happen, and that’s that violent shift tearing their world apart, and that’s going to cause major problems for them down the road, whereas, their counterpart glorified it, looked forward to it and now has benefited from it because it has completed a story. It has completed a mission for them, and I think that that’s the big difference between the criminal thought process and the good guy when it comes to lethal level of violence.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for words from our sponsors. And now, back to the show.

Okay, so the criminal has this predator orientation. It’s influenced by their past experience with violence, maybe growing up around it, experienced it first-hand. It’s shaped by the stories they tell themselves, like you talked about, sometimes these guys tell them stories, like they’re like the mob boss, or you talk about in prison, a lot of these guys would kinda harness this sort of warrior ethos, so you had the white guys getting rune Viking tattoos and the Mexicans getting a Aztec warriors and the black guys getting Zulu tattoos, so that’s a story they’re telling, like they’re a warrior. Then you say a really powerful thing that shapes a criminal’s orientation, this idea of initiation… Let’s go back to this like, what is an initiation? For a criminal, what does that look like?

Varg Freeborn: So it can be very literally, an initiation into a gang where you have to shoot someone to get in or you have to commit some kind of a beatdown or some type of a violent act to prove yourself and also incriminate yourself in front of the group, because there’s a type of leverage there that comes with that. And so that, an initiation could be something as simple as that, or it could be more esoteric in nature, that it’s not specifically called an initiation to them or their culture, but when it happens, it has the effect of making the story they’ve been telling themselves about this violent soldier, that they’re a warrior and they’re down for the cause, they’ll go down with their crew, and they actually do it. They back it up and they survive. That is an initiation from a story that was not founded on anything true, to now living a story that’s founded on truth. I do these things. I’ve done these things and I’ll do them again, and I know how to do ’em. I know how it feels. It actually feels good, and I will go it when I need to go for it, and I don’t care at that point.

And there’s also a memento mori aspect to that too. I think at the highest levels where people are accepting to live by the sword, die by the sword philosophy in their life, where they accept it, they’re like, someday I’m gonna get bucked to the pavement, but until that day, I’m the one doing the bucking. And so that’s something that comes at a time when the actual transfer to real action from thought takes place, that’s when those thoughts become really powerful and they’re backed up by experience. So you can have a guy that gets tatted out and runs around and is jacked, and he’s on TRT and he’s doing all this stuff, but he doesn’t have any real experience to back it up, so if he’s called out on the carpet and the bell rings for him on any given day and he’s gotta prove it, is he gonna have what it takes to do it? You don’t know.

I’ve seen some really tough looking guys that talk tough, act tough and lived a really tough life that hadn’t actually done anything, and when I see them get called out, they crumble, just absolutely crumble. And so there’s that moment when you’re facing someone who has had those moments and they’ve passed it with flying colors, and maybe they’ve done it multiple times. I tell stories in the book and about people I’ve met that have been shot 11 times in four different shootings. Like, you go up against that guy, you’re not going up against an amateur, not at least psychologically. He might not be a great shooter, but he’s a killer, and he’s not afraid to die. And he probably thinks he’s pretty damn hard to kill, and he’s proven that that’s true so far. So when you’re facing that type of orientation, it’s a deficit. It’s a deficit for the good guy.

Brett McKay: Okay, so with criminal orientation, the criminal tells himself stories, he’s initiated into violence, either literally or just through experience, and the more he experiences violence, the more confidence he gains in its power. He’s able to use… He’s more comfortable with using violence as an answer to situations and he’s more… I don’t know, he’s more comfortable operating outside standard societal moral values, so that’s the criminal orientation. Let’s talk about the orientation of the non-criminal. What stories do they tell themselves about themselves, and what parts of the average guy’s orientation can become deficits when he encounters a criminal?

Varg Freeborn: Yeah, so one of the most dangerous things you can do as a good guy is develop the notion of righteousness, and I’ve seen this very, very often, where they have what’s also known as good guy syndrome, where you just think, automatically, you’re the good guy, so you can just act and everybody’s going to clearly see you’re the good guy, and that’s honestly not how that goes. It’s not at all how that situation goes, and if one thing goes sideways, you’re going to be called out into the court system, and then you’re in for a long, hard haul, and it is not an experience that anybody should want to go through. There’s a very, very high chance of being convicted at some level. Most over 95% of cases in the country end in a plea bargain of some sort, based on independent study done for the Department of Justice some years ago, and that I think is very accurate from what I’ve experienced in the system. They over-charge you, they’ll hit you super hard, they’ll throw everything at you, and then that leaves room for them to strike a deal.

It’s just the same as you go for a car, you wanna buy a car and you decide, “I want $10,000 for this car,” and you’re like, “Man, I was thinking more like 7000.” Really in his head he wants 7800. So he’s shooting you the 10,000, you come at 7000, you get to 7800, you get the deal. You wanted it for less, but he gets what he wants. Courts are the same way, they shoot high, because they wanna hit you low and boom, now you’re going to prison or you have a felony on your record and you’re disarmed for rest of your life. So it’s something that you have to really consider very deeply. And I think that another problem about it, for the good guy is understanding the selective valuation of life and selective or the sliding scale of morals. And I’d like to correct you on saying that, you know, the criminal has no morals and they just do whatever they want. They do have morals, they have a selective valuation of human life, a lot of them would not… They might shoot your mother, but they wouldn’t shoot their own mother, so there’s definitely a selective-ness there, and it can change too, because one day they might not shoot the mother of their children, but another day that might change it.

So it’s very selective and it’s a sliding moral scale, and there’s also a justification built within that, and so the justification part of a sliding moral scale is the problem, that’s the hardest part to solve, once you develop a sliding moral scale, you are vulnerable to justifications like righteousness. So you feel like you’re the good guy, you’re on the side of good fighting evil, and you go too far in a defense case and you anchor shot somebody once they’re down, anchor shot them a couple of times, meaning that they go, they hit the ground, they stop doing what they were doing that was bad, and you put a couple in them just for good measure. That’s illegal. That’s not allowed. You’re going to go to prison for that in almost every case, but in your mind, at that moment, if you’ve slid your moral scale too far to one side and justified that by saying, I’m doing the world a favor here and I’m saving people’s lives, you’re gonna get yourself in trouble.

So most good people keep themselves in line by having a very static valuation of human life and a very static moral compass, whereas the criminal and the higher level military guy, sometimes even the law enforcement, have to have the sliding moral scale there because you have to be able to change the valuation of human life in the moment according to what’s being called for. If someone is in front of you that is an innocent person and they should be saved, you have to be willing to step into harms way to save them if that’s your job or if that’s what you’ve chosen as your mission. If there’s someone in front of you who is a bad actor and they’re going to hurt you or other people, you have to conversely, be able to make the decision to possibly end their life. And that’s a very tricky situation to be into morally. And so the criminal develops that very easily because they have a lot of justifications in their mind and society often backs that up, and I can attest to that because even after getting out of prison and having my rights restored, there’s several times that I’ve been road blocked even recently, in my life, 25 years after being out of prison, almost 30 years after being convicted, I still get roadblocks from things, I was just denied admittance into a technical school because of my felony.

And so these are justifications for some people to be like, “You know what, screw society, you don’t want me, you don’t want me to succeed, you don’t want me to try to do things right, so now I just move my scale and this is where I put you on the valuation of human life.” And it’s that simple, but the good good doesn’t have that, they have to be more… They’re raised in a culture that’s more static about things like, Violence is bad, don’t do violence, or things like that, and that has to change into an adjustable, manually adjustable situation, but it has to be backed up by professionalism, because if there’s not a professional structure behind it, then you can lose control of that very easily, and then you become not such a great person.

Brett McKay: Okay, so one potential problem with the non-criminal orientation is having too inflexible of a sliding scale for your decisions, you wanna be able to adjust your approach based on the circumstances, but at the same time, you can’t overly tip into justifications that seem justified at the time, but actually push you to go too far like into illegal territory. So you have to have a sliding scale, but have hard limits on it, you have to be a professional about your approach, and you described being a professional as being able to meet a minimal requirement of safety and accuracy with your weapon, if you decide to carry a weapon and conducting yourself with self-control and discretion under pressure, so you’re… You’re only gonna apply your skills and capabilities when they’re appropriate or where they’re appropriate to apply and under the confines of the law. So another deficit, you talk about an orientation for someone who sees themselves as the good guy is an over-confidence about their ability to handle violence, like they think, Okay, I’ve done the training, and if I encounter violence, I’ll just do steps one, two, and three, and it’ll work out like I expect. Can you talk about that, that over confidence?

Varg Freeborn: I think that anybody that’s been in real violence knows… We used to have a saying in prison that all the badasses were in the graveyard, and that there’s a very deep meaning to that, and it applies to soldiers, special operations guys that know that some of the best of the best have went in and died and they’ve been killed by goat herders and guys in sandals, so it doesn’t matter how much you train and how hard you go at it, there is also the factors of good days and bad days. And that’s it. And sometimes it’s just a bad day. And there’s nothing you can do about it. You’ve seen the best fighters in the world go into the ring and catch a left hook and go to sleep, because it’s just that day, and so that’s how violence goes. You’re never prepared enough to be untouchable. Untouchable is not achievable. And I think that there’s a glorification of if I train hard, I do Jiu-Jitsu, I carry a gun, a train at the range, I’m doing all this stuff, I’m just harder to kill, harder to kill, harder to kill to the point to where they really over-glorify their capabilities, and they underestimate the very negative effects and probabilities within violence, and I think the violence is a very nasty, unpredictable thing, and you could wake up on any given day and it’s gonna be a bad day, and that’s the truth of violence that I think most people miss.

Brett McKay: Alright, so the orientation of a typical non-criminal can be a disadvantage when he goes up against a criminal because he’s not familiar with the realities of violence, he’s got an inflexible moral scale when it comes to making decisions. And then he can also get caught up in his own sense of righteousness. Are there any other potential deficits in the average person’s orientation?

Varg Freeborn: We also have the exploitation of social courtesies that work against us, which is a deficit where we’re not the aggressors were not the offensive actors in any situation, we have to respond, we have to defend. That means there has to be an initial action that takes place before we can go into action as good guys. You can’t just smoke somebody because you think they’re about to do something, they have to actually begin the process of doing it for the justification, legal justification to be reached for them to be dealt with at a certain level, lethally. So there’s a huge problem with deficit of orientation, deficit of experience, and also a deficit of social courtesy, and those are gigantic problems to overcome as a good person trying to learn self-defense at a highly violent level and try to match what’s gonna come at them some day. Those are the problems that I think instructors should be trying to solve, not just getting people to shoot fast, I think that’s the last thing that they should learn, the first thing they should learn is the decision to shoot and then learn how to shoot well.

So I prioritize decision-making. In the last several years, my class is devolved into very concentrated force-on-force simulation UTM training away from a broad scope of square range skills and live fire skills and this and that, and some combative and all this, and I’m like, Alright, let’s go down to the very basics of making decisions in tough situations and putting people in hard situations, and one of the unique things about my classes that I would do when I did the force-on-force training was I would make… I didn’t bring professional role players in, I would make the students play all of the roles, so at any point in a class, you could be a good guy, you could be an armed bystander, an unarmed bystander, you could be an observer or you could also be the bad guy. And one of the things I wanted them to do was be able to see the perspective of the bad guy entering the situation trying to accomplish a goal, and look at all the problems he has to solve because he has problems too, he has an orientation problem, he has confidence problems, he has analysis and synthesis that has to take place.

It’s not just as simple as walking in and robbing somebody. I think that people have pushed this narrative that the wolf is at the door and he’s vicious, and they don’t think like you and it couldn’t be further from the truth. We all have the same exact processes that take place and being able to see it from that other side, that other perspective gives you that insight to how to get into that, like how they like to say, Get into their loop and disrupt it. Right. So you’re getting into that mindset and seeing the problems he has to solve so that you can create those problems or manipulate those problems to your benefit and against his. I think that’s the biggest thing that we can accomplish there.

Brett McKay: Okay, yeah, so you’re big on simulation training, so at least you’re getting a little bit of a feel of what an actual violent encounter is like rather than just doing more of a kind of scripted training, and I’d like to talk more about the kind of training you recommend in a bit, but you mentioned earlier the idea of having a mission, can you talk about what it means to have a mission, and what part does that play in creating an effective orientation?

Varg Freeborn: Mission is the most important thing. It needs to be established when you embark on a journey of self-defense and carrying a weapon and things like that. If you’re not clear with yourself about what your actual mission is, then you will not be able to train properly, equip properly or conduct yourself properly in stressful situations because you don’t have the proper boundaries and parameters defined. The mission defines your boundaries parameters, it defines what you’re willing to fight and die for, it defines what is legal, what you’re allowed to do, who you’re allowed to do it to, for example, a civilian that’s carrying a gun needs to understand the state they live in, the laws for self-defense in the state they live in, is there a duty to retreat, is there not a duty to retreat, is there a stand your ground, is there castle doctrine. Like all these things need to be understood in the mission, because if your mission is not in line with the external boundaries, with the laws and where you live, or the use of force policies with the agency that you work in then your actions and your training and your equipment are gonna vary outside of those allowed parameters, and you’re gonna get yourself in trouble there.

So I think that understanding how that works and where your mission is at first puts you in line with the rest of the things that come after that, and that is… That is the most important thing to really consider if you don’t have… A lot of times I would start classes, when I used to do live fire classes, I’d say, “You know, you’re carrying a gun, you wanna defend yourself, your family, so what’s your mission?” And most people would say it’s because I want to make sure I make it home and my family makes it home so we can live our life together, and that’s a good mission. I like it. And then I put up a scenario where you walk into a gas station and the guy’s got… A bad guy’s got a gun to the clerk’s face and he hasn’t seen you yet, you can make the decision to take the shot, or you could step outside and call the police and go home. And a lot of people will say, I’m taking a shot, and I say, Alright, let’s examine that for a minute. If you got out of there and got in your car and call a place and went home, would you accomplish your mission of getting yourself home and making sure you and your family make it home safe? Yes, you would have accomplished your mission.

If you went in and got into that fight and you got shot by the clerk because your gun jammed or you slipped on some water or whatever could happen in violence and you die, did you fail at that mission of making home and taking care of your family? Yes, you failed. So what is your real mission? Now, I’m not downing people, if they say they wanna jump into fights and protect people wherever they go, that’s fine, but just state that mission clearly to yourself and to your family, and then train for that mission, like don’t tell yourself you’re only in it for yourself and your family, if you’re gonna jump in and defend whoever else is out there around you and vice versa. Don’t say that you’re gonna jump in wherever you can, and then you don’t protect your own family when you need to, so having your mission stated is the way to get all that squared away. And I think that’s gonna attack the root of that initial problem.

Brett McKay: Understanding the orientation of a criminal, understanding the orientation of just a regular good guy who just wants to get home to their family, take care of their family, how do you think that should change their approach to self-defense, once they have that understanding?

Varg Freeborn: I think it’s gonna give them a more realistic perspective of who they might be dealing with, and that’s very, very important because I don’t think that a lot of people have a realistic sense of who their opponent might be. And one of the things that I encourage people to do is spend some time watching death row interviews, and there’s just countless shows on criminals and talking to especially murderers and serial murderers and things like that, and just get a glimpse of what the mindset is in some of these people and their philosophies and their viewpoints, and how they just have zero valuation of human life for certain people, and certain people meaning innocent people that they don’t know, they just do not value your life at all, they don’t value your kid’s life, they don’t value your parents life, they do not value you. And so understanding that is going to give you a better realistic viewpoint of the level of threat you could be facing. Also understanding the level of violence these people have experienced and how many times they’ve been involved in violence, and you may never have been in a real fight in your life.

And so you’re going up against… It’s like going into an MMA ring with someone who has not only trained but has 100 fights under their belt and you went to a couple of eight-hour classes, it’s just ridiculous to think that, right? So it’s the same thing, you have to get a realistic view of this to understand, Okay, this is what I’m up against, and then establish your mission, and with those two pieces of information, now you can go and put together a proper gear and equipment acquisition protocol and a proper training protocol that are going to help you address that problem better, because if you don’t do those two things first, then everything you do after that is just you are winging it.

Brett McKay: Yeah, let’s talk more about that training protocol, basically, what we talked about today is that when your OODA loop is going up against the OODA loop of a criminal, the criminal has certain advantages while you, the non-criminal has certain disadvantages. So I guess the question is, what can the average guy do to close that gap, you’ve talked about the importance of simulated training and role play, which can give you a closer approximation of what actual real world violence is like, but beyond that, what do you recommend training wise?

Varg Freeborn:0:55:13.1 VF: Personally, I think that your individual strength and fitness is your most important component, if that’s available to you, now, if you’re handicapped or you have some type of a disability that prohibits that, then you have to recognize that deficit and go harder on the other elements like weaponry, things like that, because that’s a fall back, that’s not to go-to, but most people put that as a go-to first, and I’m telling you that, for example, we referenced me being a strength coach, I run an online coaching program, and I have several clients that are either competitive in some sport or another, or they wanna… They’re training self-defense, they just wanna be stronger and better, and for me, that’s also something that was born out of prison, I was fortunate enough to land in prison during a time when they still had free weights and we still had weight piles, amazing experience. I’m certainly glad I got to experience it. There’s nothing in the world like the aggression of a prison weight pile. It’s very, very unique experience that you cannot duplicate, and I lived on that pile for the whole time that the weights were still in there, and that’s where I learned…

And this was at a time when… This was the early ’90s, and I was probably about 30 miles away from where Louis Simmons was, Westside Barbell. And so at that time, Louis had a lot of very questionable characters coming through that gym, and some of those same guys were coming through the prisons and stuff, and the information was just filtering out, and so I learned very quickly. I went from being a 130-pound kid going into prison to hiting about… I peaked out about 200 pounds within the first two years, and I was very significantly different, I was different psychologically, and I was different physically, and I found life to be much easier, be it both in fighting and in avoiding fights when I became strong like that, and it taught me a very, very important lesson about strength and its importance to survival. Also, there was a difference between training in an atmosphere like that and training out here on the streets, most people go to the gym here, they’re trying to look good to attract a mate, or they just wanna be jacked and intimidate people or just wanna look cool on Instagram or whatever their motivation is, and some people is for health, but in there, it’s purely motivated by survival, like I need to get big, I need to get big fast, and I need to be able to fight. I just can’t be a big dude just lunking around.

I have to be able to run, I have to have some cardio, I have to have some endurance, and so the motivation for training is very different, and that was ingrained in my mind, and today I have my own gym at home, and there’s not a day that I step into my gym that I don’t slap back into that mindset that I was in 27 years ago on the prison yard weight pile. And I’m right back to where I was then. And this is, it’s ingrained. And so I think that if a person is going to train for this, if they’re going to set themselves up to be prepared to deal with a self-defense situation, your first and most important thing has to be your strength and fitness. Not only will it help you avoid fights because you’ll look more formidable and that’s not always a deterrent, but it does work in some cases, but if you do actually have to fight, you’re gonna be mentally tougher because being willfully uncomfortable under weights and pushing yourself in a training program is a very difficult thing to do, and it’s going to cultivate mental toughness, no matter how you do it, you’ll also be physically stronger, and so you’ll be much more capable of handling someone when they get a hold of you.

And also too the biggest threat to your life is heart failure and the multiple diabetes and multiple diseases and things that happen that are killing people by the hundreds of thousands because they’re obese or out of shape or out to weight, are overweight, they get older and their muscles atrophy, their skeleton begins to droop and sag and their joints become disaligned and everything is just based on the degradation of their strength and integrity, and so in today’s world where we have this virus, and it’s already been proven that viruses of this nature, lean muscle mass is generally an indicator of how well you will handle it, the higher lean muscle mass you have, the less severe the symptoms typically are, and that’s been found in studies in the last two years and before. So it’s just a general good idea And it cultivates the foundation for everything else.

A lot of guys will jump straight into BJJ, and the problem I have with that is that you’re getting off the couch and you’re going to do something that’s great, but you’re going and putting loads on your joints and you haven’t done anything to prepare those joints to handle those loads and that’s physiologically bad, it just does not make sense from that from that standpoint. As a barbell and strength coach, I like to say, Okay, let’s do some body building, let’s do some volume work to build up the connective tissues, the ligaments tendons, the small musculature around the joints, gets you strong in those areas before we start one rep maxing, before we start BJJ, before we start all of those things. And that’s just the approach I like to take with it, and then weapon skills, of course, it’s a good step if you’re so inclined to use weapons or carry weapons, make sure that they are the type that are approved for use in justified self-defense in your area, in your state, and also take instructors who emphasize decision-making over flash. That’s the biggest piece of advice I could give you for weaponry, but those would be the order I would put things in, so you have your strength and your health and fitness, your comparatives and then your weaponry.

Brett McKay: Okay, I like that. That’s a good rubric to follow. Well, Varg, it’s been a great conversation. Is there some place people can go to learn more about your work?

Varg Freeborn: Right now my main website is just vargfreeborn.com, and I don’t have… Like I said, I’m semi-retired from classes, so I’m doing one-on-one work and I’m doing some strength coaching and some lectures, some lectures here and there, but if someone wants to do some work or they’re interested in something, they can contact me through that website and we could probably work something out for sure.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Varg Freeborn, thanks for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Varg Freeborn: Alright, thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Varg Freeborn, he’s the author of Violence of Mind and Beyond OODA. They’re both available on amazon.com, you can find more information at his website, vargfreeborn.com, also check out our show at aom.is/orientation where you find links to resources and we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast, make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles, there’s about pretty much anything you think of, and if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium, head over stitcherpremium.com, sign up using code manliness at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher App Android, iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM Podcast, and if you ever done so already, I’d appreciate you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always thank you for the continued support. Until next time, it’s Brett McKay reminding you to not only listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.

Tags: Self-Defense & Fighting