Hardtack.

The name sure doesn’t make it seem appetizing, does it? And yet it has left an indelible mark on the edible history of the world, sustaining and fueling explorers and armies for a few hundred years between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Not quite bread, not quite a biscuit, hardtack is a hard (very hard; often rock-like, in fact), dry, and unleavened foodstuff that is most comparable to a thick cracker. It’s made with a rolled dough that is best described as parched, and it’s baked for a comparatively long time in order to eek out every last bit of moisture while also hardening the end product. This process is what makes hardtack nearly un-spoilable. There’s just nothing in it to go bad.

It’s inexpensive to make, requiring just flour, water, and salt. It’s lightweight, easily packable, and damn near indestructible, able to withstand severe jostling (like in a ship’s hold or in a soldier’s haversack), as well as intense temperature fluctuations and extremes. Finally, and most importantly, it lasts forever. Specimens from the Civil War can still be found in museums and are theoretically edible (you can watch a guy eat one from 1863 here).

All of which makes hardtack the perfect — albeit not-quite-enjoyable — survival foodstuff.

As such, you’ll find some folks making it even today as an emergency ration to have stored in the home. While modern ingredients and flavorings are often added, those actually decrease its shelf life. It’s not like you’re going for flavor in that scenario anyway, so why bother? Many folks will stick to the original recipe and store hardtack for years and years, and that’s what I’m going to show you how to do.

Beyond preparing it as a survival item, it’s fun to do just to get a literal taste of history; you can eat basically the same thing that soldiers and ocean-going explorers ate hundreds of years ago. That’s kinda cool.

Before getting to the recipe though, let’s take a quick look at that history.

A Brief History of Hardtack

A piece of hardtack, alongside a butter knife, fork, and spoon from the Civil War mess kit of a Union soldier.

While dry unleavened bread products have been around basically as long as civilization, hardtack as we know it really gained steam with Europeans as they crossed the Atlantic to survey the New World in the 1500s. Back then it was often called cabin bread, sea biscuits, ship biscuits, and more. (Though behind the cook’s back it was often called dog biscuits, molar breakers, sheet iron, and tooth dullers.) Hardtack was a staple of the Royal Navy all the way through the mid-1800s and was often manufactured in bulk many months prior to ingestion.

As the exploration and settlement of the American landscape increased, so did the production of hardtack for both sea voyages and long overland trips. It was particularly useful on the epic wagon trains to the West, especially as gold and silver were found in California and then the Rocky Mountain region. Few rations could hold up as well on such lengthy journeys.

Of course, most people’s notion of hardtack comes from the Civil War. It fed soldiers in both the blue and gray, sustaining them on long marches and campaigns with biscuits that in some cases had been in storage since the Mexican-American War of the mid-1840s. As one soldier ruefully recounted, since fresh foods were obviously hard to come by, hardtack was an ever-present companion in the camps:

We are living very high nowadays, have pork, hardtack and coffee for breakfast and of course for dinner coffee, hardtack, and pork for change. Then for supper we have a little coffee, pork, and fried hardtack.

Later on in the war, as resources dwindled for both the North and the South, it was common for whole days to pass with men subsisting on just a few 3×3” pieces of hardtack and some coffee — usually together. Indeed, the biscuits were often so tooth-chippingly hard that they would have to be dipped in some liquid — water, broth, and especially coffee — or broken up by a rock or the butt of a gun and cooked in grease to make a kind of mash.

After the Civil War, while America was focused on Reconstruction (rather than exploration) and decreasing the size of the army, hardtack didn’t have much use. It was briefly seen again during the Spanish-American War at the end of the 19th century, though Theodore Roosevelt said that the humid, moist Cuban environment often turned the crackers moldy. Hardtack then fell out of use as preservation methods improved and the military focused on providing its servicemen with foods more palatable than what amounted to baked flour. (Many WWII soldiers would argue, of course, that Spam wasn’t such a great improvement!)

While nearly always alluded to with derision and sarcasm, hardtack literally kept men alive for hundreds of years, through world-crossing ocean voyages, long overland explorations, and military engagements.

Now, let’s learn how to make it. Whether preparing as a batch for survival prep, or just for the sake of seeing what it’s like, I guarantee you’ll have some fun.

How to Make Civil War Era Hardtack

There isn’t really an agreed-upon ratio of flour to water (or salt either). This is a “recipe” that, unless made in a factory, is different every time it’s made. Can you imagine pioneers or hardened Civil War soldiers measuring out precise amounts? Of course not. They’d mix some water into a pile of flour until it came together just enough to be baked.

That said, below is a starting point to use that should make about 15 crackers.

Ingredients

- 2.5 cups flour (~315 grams if using a scale, though, again, precision really does not matter here)

- 1/2 cup water (some old recipes show even less water; I ended up using just under 1/2 cup)

- 1 tsp salt (optional, but was certainly added when available to the folks cooking it)

1. Mix flour and salt.

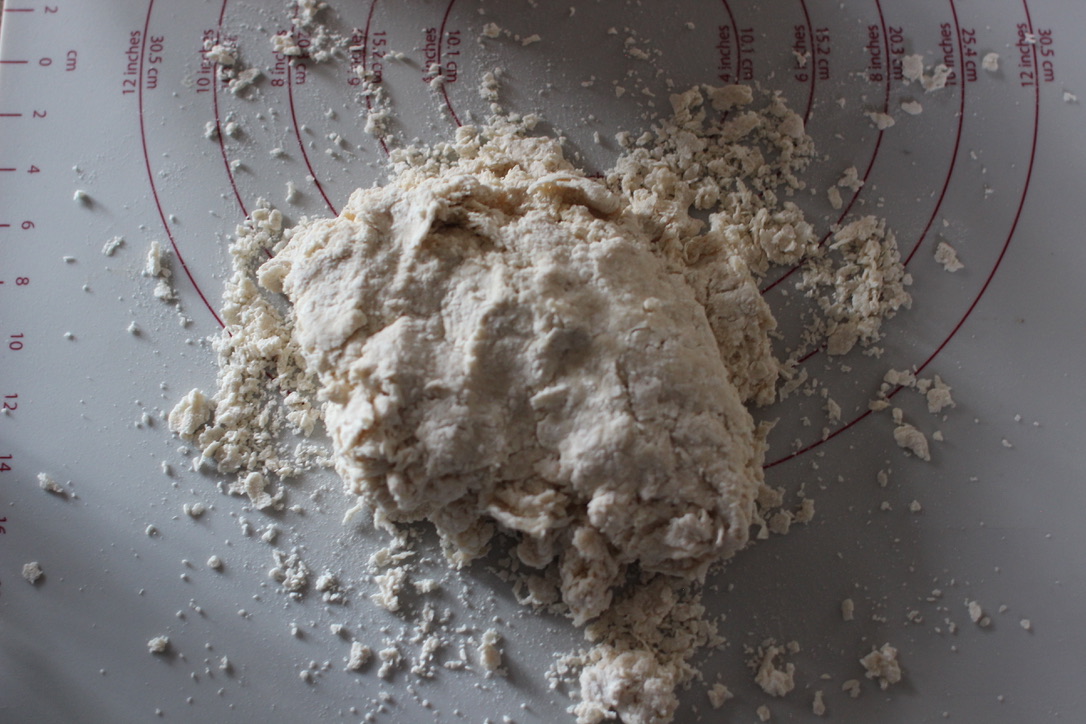

2. Begin adding water in small amounts. Knead.

Just starting to come together.

Add about 1/4 cup water at a time, kneading as you go, and mixing until you absolutely need more liquid to get the dough to come together. If it’s excessively sticky after all the water is used, add some more flour, one tablespoon at a time.

At the end, it’s a little easier to turn the dough out onto the counter/baking mat to continue kneading.

3. Roll the dough.

Using a rolling pin, roll the dough until it’s about 1/2” thick or less.

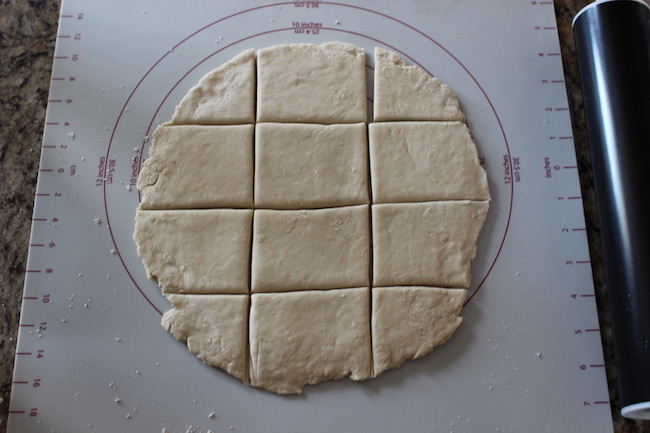

4. Cut into “crackers.”

Using a knife (or dough cutter if you have it), cut the dough into squares. As mentioned above, 3×3” is how big they were during the Civil War.

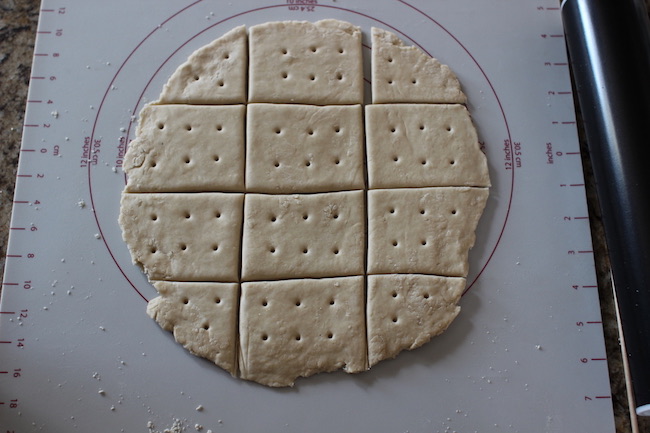

5. Dock the crackers.

This just means poking holes in them, which you do for a few reasons: 1) it helps them bake more evenly, 2) it creates spots for moisture to escape (a good thing in this case), and 3) it makes it easier for the cracker to be broken apart after cooking. You can buy a dough docker, but using any implement with a pointy end — like a skewer or kabob stick or even just a fork — will do.

6. Bake.

Pull out of the oven just as they start to brown around the edges. I pulled mine out at 28 minutes.

Most of the bread I bake is cooked at a rather high temperature. With hardtack, though, you want to go low and slow. Bake at 375 degrees for about 30 minutes, until the surface just begins browning. Keep an eye on it at the end.

7. Allow to cool completely.

After baking, leave it out for several hours so that it completely cools and no moisture remains. In a dry environment, you can leave it out for days if you’d like.

8. Consume!

To really experience your hardtack like a soldier did, dip it in coffee or break it into chunks and serve in broth to make a soup. You’ll notice that it’s not particularly tasty, but it would get the job done in a desperate situation.

9. Store. Consume again.

Store in any sort of air-tight container, be it tupperware or sealed bags. If preparing for survival purposes, make a large batch and vacuum seal it in bags. If just for fun, store in tupperware for a few weeks or months and then try it again!

_____________________________

Sources

If you’re into Civil War history, the below two books are a hoot to read. The things soldiers did to improvise with food and drink and other daily life activities are really quite something to read about.

Daily Life in Civil War America by Dorothy Denneen Volo and James M. Volo

A Taste for War: The Culinary History of the Blue and the Gray by William Davis