A lot of ink has been spilled on time management and productivity hacking; you can find endless tips on how to master your workflow, tame your inbox, slay your to-do list. Far less examined, however, is the philosophy that underlies these strategies. My guest says that when you do examine that philosophy, you find it doesn’t actually align with lived experience.

His name is Oliver Burkeman, and in his book, 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, he forwards a philosophy of time management that is more realistic and humane. Today on the show, Oliver makes the case for a kind of contrarian way to make the most of the 4,000 weeks of the average human lifespan, beginning with why he reached a point in his own life where he realized that standard methods of productivity hacking were futile and just made him feel busier and less happy. We then get into the fact that we’d like to do an infinite number of things, but are finite beings, and how this contrast creates an anxiety that we attempt to soothe and deny through productivity techniques. We then discuss the problem of treating time as a thing, a resource that’s separate from the self, and how one antidote to this mindset is to do things for pure enjoyment alone. Oliver explains why engaging in efficiency for its own sake only creates more stuff to do, and why recognizing you can never “clear the decks” of your daily tasks, nor get everything done, can actually help you focus on the things that matter most. We end our conversation with why really digging into a deep philosophy of time by facing up to its stakes and engaging in what Oliver calls “cosmic insignificance therapy,” can allow you to live a bolder, more meaningful life.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- AoM Article: Your Three Selves and How Not to Fall Into Despair

- AoM Article: Good News! Your Life Isn’t Limitless!

- AoM Podcast #602: The Case for Being Unproductive

- AoM Article: 75+ Hobby Ideas for Men

- AoM Podcast #527: The Journey to the Second Half of Life With Richard Rohr

- Tombstone “there is no normal life” scene

Connect With Oliver

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript!

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow others to enjoy it as well. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Now, a lot of ink has been spilled on time management and productivity hacking, where you can find endless tips on how to master your workflow, tame your inbox, slay your to-do list. Far less examined, however, is the philosophy that underlies these strategies. My guest says that when you do examine that philosophy, you find it doesn’t actually align with lived experience. His name is Oliver Burkeman, and in his book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, he forwards a philosophy of time management that is more realistic and more humane. Today on the show, Oliver makes the case for a kind of contrarian way to make the most of the 4,000 weeks of the average human lifespan, beginning with why he reached a point in his own life where he realized that standard methods of productivity hacking were futile and just made him feel busier and less happy.

We then get into the fact that we’d like to do an infinite number of things, but are finite beings, and how this contrast creates an anxiety that we attempt to soothe and deny through productivity techniques. We then discuss the problem of treating time as a thing, a resource that’s separate from the self, and how one antidote to this mindset is to do things for pure enjoyment alone. Oliver explains why engaging in efficiency for its own sake only creates more stuff to do, and why recognizing you can never “clear the decks” of your daily tasks, nor get everything done, can actually help you focus on the things that matter most. We end our conversation with why really digging into a deep philosophy of time by facing up to its stakes and engaging in what Oliver calls “cosmic insignificance therapy”, can allow you to live a bolder, more meaningful life.

Also, I mention a poem during our conversation that I decided to recite full in the show, so be sure to listen to the end, so you can hear it. You can find a link to that poem in our show notes, which can be found at aom.is/fourthousandweeks.

Alright. Oliver Burkeman, welcome to the show.

Oliver Burkeman: Thank you very much for inviting me.

Brett McKay: So you got a new book out, it’s called, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. And you take a deep dive into philosophy, psychology, sociology, history, religion, to suss out a philosophy of time management, that’s, I think it’s a humane philosophy of time management, and you make the case in the book at the beginning, that our popular idea of time management we have, like getting things done in black zero, being efficient, is that it’s paradoxical ’cause it allows us to get more things done, and these systems do work to help you do a lot more, but at the same time, they cause us to feel busier and busier. When did you start noticing this paradox in your own life?

Oliver Burkeman: Well, I mean, for years, I wrote a column for the Guardian newspaper about psychology, productivity, science of happiness and all the rest of it, and one of the things I got to do that was indulge my, at that point, life-long interest in productivity systems and trying to find the technique that would make me feel perfectly in control of everything, so that I could handle anything that might be thrown at me, fulfill all the work ambitions I had while making plenty of time for all the other things I wanted to do and sort of never getting there, because you’re sort of in this mode of constantly feeling like it’s next week or next month or the next system that you implement, or that you’re gonna wake up tomorrow with 10 times as much self-discipline than you’ve ever demonstrated in your life before up to today.

And so it’s that sort of gradual process of realizing that I wasn’t gonna get there that way, and that in the meantime, what happened was I got busier… Yeah, I did process more things, I did get more things done, but firstly, I didn’t get this kind of peace of mind, this sense of tranquility with respect to time. And then secondly, they weren’t necessarily the most important things. In fact… And I argue about this in the book, that there’s a reason to believe that you’re gonna do more and more of the least important things, the more you focus on just becoming more efficient and sort of productive for its own sake. So that was a sort of slow realization. And then I talk also about having this epiphany sitting on a park bench on a winter morning in Brooklyn, where I lived then, and just sort of suddenly realizing like, “Oh, none of this is ever gonna work. I’m never gonna reach this level of total control and security with respect to time that I’m fighting for here.” And how sort of liberating it was to see that I had been trying to do something that is kind of, I think, inherently impossible for human beings to do.

Brett McKay: And I’ve experienced the same thing you’ve experienced where I went through that, I think every person, if you’re a modern human being living in liquid modernity and hyper-individualistic, hyper-capitalist society like, that you go through a productivity phase. I think everyone does that. It’s a rite of passage at this point. And then… Yeah, you finally realize, “Man, none of this works.” And so you’re always looking for the next best thing. And one of the cases you make in the book is that part of the problem that underlies all of our frustrations with popular time management paradigms is that it causes us to think of ourselves as limitless while ignoring the fact that we are finite beings. So how does thinking of ourselves as limitless, how do you think that makes us miserable?

Oliver Burkeman: Great. Yeah, no, that’s exactly the sort of underlying thing I’m trying to get at. I think that we are made deeply uncomfortable by all the ways in which we are limited, especially the ways in which we are limited when it comes to time. We only have so much in a day, we only have so much in our life and we don’t know how much that’s going to be. We can only focus on one thing at a time. And even more profoundly, I think we can’t control, we can’t be in control of how our time unfolds in the way that we would like to be. In other words, you launch into some creative project, for example, you can’t know it’ll work out, you can’t know you will not encounter insurmountable obstacles, you can’t know this all in advance, so we’re sort of vulnerable in time, in a way that I think… And to time, in a way that makes us really uncomfortable.

And so we do what human beings since beginning of history have done when they feel uncomfortable about something, which is to pursue methods of emotional avoidance, ways of not feeling the discomfort, and I think that time management and productivity techniques used wrongly in the wrong spirit are absolutely an example of this kind of emotional avoidance, they can fuel this illusion that you’re en route to this position of limitless-ness, this kind of state of perfect optimization where you would never have to make tough choices about what to spend your time on, you would never have to disappoint anybody who might have any expectations of you.

Any obligation you might feel, or goal you might set, there’ll be a way to get that done too. Of course, it’s never happening in the present moment because we are limited and it’s not actually possible, but you’re sort of kept comfortable in a way by chasing this feeling that it’s gonna happen, and that you’re almost there. And so I think all sorts of aspects of human culture get drafted into this kind of emotional avoidance in many different domains, but productivity culture is just one of them, and the one that I was particularly using, I guess, for many years for just that kind of avoidance of the experience of reality, I guess.

Brett McKay: And going, you go to a philosophy a lot, and as I was reading that section about this idea of limitless-ness, but we’re finite beings, remind me of Kierkegaard, he said that was the human condition, we are the infinite and the finite combined in one, so humans have, unlike other animals, humans have the capacity to think about eternity or forever, they can see lots of choices, animals, they’re not really thinking about too much. But the problem is, Kierkegaard says that’s the source of a lot of our anxiety or our angst, we wanna do all this stuff limitless, but we are finite beings. We have to figure out how to manage that paradox.

Oliver Burkeman: Right, that’s exactly it. And just to sort of bring Kierkegaard down to Earth in a sort of maybe disrespectful to Kierkegaard way, but yeah, it’s like on the level of your daily productivity, you can imagine an infinite number of things that you might want to do, you can feel an infinite number of obligations or duties, you can set all sorts of visions for where you want to be, and there’s no limit to those things that happen in the world of your consciousness, but there’s obviously very, very severe limits when it comes to your time, your stamina, all the rest of it. And yeah, there’s a sort of constant disconnect there, so I don’t think that you can ever really get away from that sort of anxious situation, I think there’s something inherently anxiety-inducing about this, I think Kierkegaard said that too, but you can choose whether you’re going to try to sort of dull the pain completely and just end up wasting time as a result, or whether you’re going to make some effort to sort of lean in to that discomfort in the service of carrying out some goals that you really care about.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I think what your book is trying to do is trying to help readers embrace their finitude a bit more, like don’t discount the infinite, but you have to wrangle it a little bit and just realize you have a limit, you have to work with it and I think what you’re saying is a lot of time management techniques, and it encourages us to think that, “Oh, we can get more and more done as much as we want, we can have it all,” and you’re saying, “Yeah, probably… ” Well, no, that’s not gonna happen.

Oliver Burkeman: Right. And I just wanna say something in defense of some of those techniques, I think a lot of this is to do with the spirit in which you try to integrate them into your life, there are certainly some time management gurus who are guilty of promoting this notion that full control and mastery over time in a way that humans, I think can’t have, is on the cards, but lots of these techniques are perfectly useful, if all you’re using them for is to organize your day a bit more, make slightly better choices between competing priorities. The problem is that… I think a lots of it, anyway, we sort of glom on to them as if we’re going to achieve some kind of salvation through them, and the salvation in question is actually, if it were real, it would involve somehow getting outside of reality, getting outside of the situation in which we all inevitably are in.

Brett McKay: And one of the things you do too, is you do some genealogy of our approach to time to figure out what it is, how did we get this time management system or these systems in place, this idea of time that makes us think we can control time. And you go back in history, and this idea that we can manage time or control time is a relatively new idea, it’s a very modern idea. If you go back to Medieval serfs, they never would ever thought, it wouldn’t have crossed their minds that time is a resource. So how did… If you went back to your great, great, great, whatever grandfather who was a serf in England, how did they think of time and how does that differ from how we think of time and how did we get to where we are now?

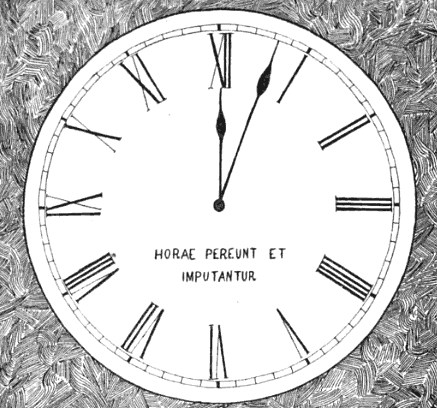

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah, it’s not a straight linear story because you certainly see very modern ideas about time expressed in the ancient world, and on the other hand, I think there are probably some indigenous cultures, even today, who have an approach to time that feels more like something that I’m talking about as belonging to pre-industrial cultures, but it’s just this whole incredibly basic idea that time is a thing. I mean, it’s very hard to express this, and in the book, I end up using this phrase, thinking of time as a “thing”, meaning as some kind of separate entity from yourself, not merely the medium in which your life unfolds, but somehow a resource to be maximized or something you have to be careful not to waste.

I think whenever anybody today visualizes time in the context of work, say, “Do I have enough time to do these three things by Friday. ” You’re thinking, you’re imagining a calendar or a yard stick or a clock face. This whole idea that time is this objectified thing that you then have to deal with or that can sort of hound you, none of that would have arisen in the first place to a peasant in early medieval England. I think they would, we’ve got some reason to believe from the historical record, they would have lived in what anthropologists called Task Orientation, this idea that the rhythms of life just emerge from the things that you’re doing in your life and in your work, that it’s not like you make a schedule and you can decide where to slot things in, it’s like the cows need milking when they need milking, and the harvest needs harvesting when it’s ready to be harvested, and a productivity guru who arrived on a medieval farm and said, “Look, it’s really useful to batch your task, so why don’t you do all the milking of the cows for the month today, to get it out of the way.”

Obviously, that’s absolutely absurd. You’re too yoked into nature and the rhythms of reality, to make that kind of decision, to have that kind of pictorial control over time, and I think most of us have some experience with this today, it’s just not the norm anymore, anyone who has been a parent of a very small child, a newborn, I think has experienced being in that world where things just happen, the baby needs to be fed when it needs to be fed and diapers need to be changed when they need to be changed, it’s not something you can ever hope at least at the beginning to schedule, and I think that arises in lots of other contexts as well, so all I really wanted to do here was to just say, “Hey, let’s at least remember that our main way of relating to time today is not the only option it is historically contingent. It is something we can sort of hope to get outside of at least for some hours of the day or some weeks of the year,” which is not the same as saying, “I think we should live like medieval peasants” ’cause that is a terrible, terrible life in all pretty much every other respect. [chuckle]

Brett McKay: And again this transition to thinking of time as a resource, I sort of went through different cycles, like monks were involved, then capitalism in 19th century, where we shifted from task-oriented work to, you’re gonna work by the hour. And then now we’re kind of stuck with that, but what is it about thinking of time as a resource as opposed to thinking of time as just being… I don’t know, not even… It’s not something to be used. It just is, how to see time as a resource, how does that make us miserable, you think?

Oliver Burkeman: Well, firstly caveat, I think it’s probably essential to almost all the achievements of the modern world, so I don’t think it’s something we can just get rid of, but I think it does have this strong set of problems as well, and there are a number of different ones, but the sort of fundamental one, I think is just that this instrumental approach to time, this idea that you’re in a use relationship with time and you’re always on some level asking, “Am I making the best use of my time?” Or sometimes it’s more in certain times of history as well, employers asking how to get the best use of time out of their employees, whatever, it broadly has this effect of postponing the value of life, it makes everything you’re doing now valuable solely in terms of what it’s leading up to. And it makes that… This is a thing that makes it very, very difficult to sort of extract a sense of meaning from life in the present, because you always got an eye on the future, to the moment when this is all going to deliver or fail to deliver in some future, accomplishment. Which of course never happens because the future remains in the future.

Lots of other different ways in which this causes problem, but I think it leads overall to the sense that you’re in a kind of a struggle with time and you’ve got to try to subdue it somehow got to try to get on top of it or out front of it, whatever special metaphor you wanna use, and the problem is that’s always gonna be a recipe for a kind of never-ending anxiety and stress because actually, you’re not really relating to time, you’re relating to a certain set of ideas about time, and the problem with declaring war on time is that, eventually time is always going to win that struggle, and it just sort of keeps going on regardless, no matter what you do with it. If that makes sense.

Brett McKay: No that makes sense. And I really related this idea of treating time as a resource causes you to make… Treat time as an instrument, because a lot of time management is all about planning for the future, and I think if you’ve grown up in any Western country, you’re kind of set on to this… It’s like in the culture, it just seeps into you go to… The idea is you gotta get good grades in high school so you can get into a good college, and then you gotta get in a good college, so you can get the good job, then you gotta get a good job so you can be an attractive mate and get a good house. So you’re never… You’re always doing something for something else and you’re never… And it just feels like it’s like a never ending… It’s like the rat race is a never-ending conveyor belt, and it just makes you feel terrible and then you always reach that point, once you achieve all those things, “Alright, what now? , What do I do now? What happens now?”.

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah, completely, and of course, we do need to do those things, I would be a complete hypocrite if I claimed that I don’t live many suaves of my life with a strong focus on the future and instrumentalizing the present moment, but there’s two things. Firstly, it doesn’t need to be the sole focus that you take to any moment of experience, I don’t think, and secondly, it’s very useful… I’ll get a book to try to make sure that there is something in your life, some activity, some past time that is just for itself alone that resists that instrumentalization. These are things we tend to think of as hobbies, which is sort of in many circles, I think is sort of a slightly embarrassing, cringe-making kind of idea to deliberately cultivate a hobby which has no purpose other than itself, but I think it’s cringe-making because it’s so antithetical to the prevailing message of the culture, which is that nothing is valuable unless it is for some future, some future purpose. Preferably financial profit. So yeah, I think it’s just something to pay attention to and make sure you don’t eliminate entirely from a life.

Brett McKay: And what’s sad and interesting is that we’ve even instrumentalized hobbies, and it used to be, you could have a hobby and people are like, “Oh yeah, you build model trains, that’s fine”, but now it’s like, well, if you’re gonna build model trains, you gotta have a social media account where you’re… As a model trained influencer yet there has to be a side hustle. So you can’t just have model training just because you enjoy it.

Oliver Burkeman: Right. Yeah, side hustles. Side hustles are cool, hobbies are uncool, and I think there’s a reason for that. And so one way around that, which I certainly do in my life is to find something that you enjoy, that you’re not very good at. I really enjoy hammering out various piano rock songs on the keyboard that I have here, but I tell you, I’m not good at it. I would not perform for love or money, and I certainly wouldn’t get any money for performing, that’s a useful thing in a way because there’s no pressure there, there’s no attempt to think that I might one day instrumentalize it, and obviously, what I do professionally, writing is absolutely different from that. It’s really hard to not think about writing with one eye to, well, “Is this is gonna be a huge success? Is this book gonna sell a lot of copies?” etcetera, etcetera. So good to have something that you suck at, but that you find enjoyment in.

Brett McKay: There’s a word for this type of activity, it’s a Greek word you threw but I can’t remember it. It starts with an A. There’s telos activities…

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah, that’s atelic, actually. It’s Greek in a sense, it’s really, it’s essentially coined by contemporary philosopher, Kiran Satyr, but what he means as I understand it, is an activity that is not defined by its telos, atelic. It’s just something you do for itself alone. Hiking is the other example I talk about at length in the book. If you wanna get more efficient at hiking where you drive the car somewhere and then you walk in a loop or you walk to a point and turn around again, the most efficient way to do a hike, is just not to go. Then you’re back at the starting point immediately. So doing that for some future purpose, it’s not a perfect point ’cause maybe you get more physically fit through hiking or you update your social media account with great pictures from your hikes, but basically hiking is a thing, is an atelic activity par excellence really, because you just do it, you’re not leading up to something, there’s not gonna come a time when you say, “I have completed all the hiking I planned to do in my life.” It just resists all of those kind of pressures, I think.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so that’s a way to rebel against our instrumental culture, just do something ’cause you enjoy it and then that will bring you happiness, and it’s like that happiness is the side effect, that’s another thing people can get into like, “Well, I read this study, if you have a hobby, it will make me happier, and by being happier, I’ll be more productive and blah, blah, blah.” You can’t go down there just like, no. Just play piano because you like to hammer out piano rock tunes. That’s it. That’s it.

Oliver Burkeman: Right, right. And yeah, that’s just instrumentalization again, right? Chasing happiness. We’re made to do this. I don’t think that people should feel bad about this sort of natural tendency towards achieving future goals, I just think consciousness of what’s going on can be really helpful because then it makes you… Nobody wants to spend their whole life only waiting for the moment on their death bed where they get to say like, “Oh, that was enjoyable in hindsight.” right? Nobody wants that. So once you see that that’s part of what you’re doing, I think it becomes pretty natural to ease up on that focus a bit.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Yeah, and you quote Richard Rohr a lot and we’ve had him in the podcast, and he has that idea is that there’s a first half of your life where you’re doing the instrumental stuff, like you’re trying to build a career, you’re trying to do those things, but he said at a certain point and this is gonna happen at any time in the lifespan, you’ve gotta move beyond that and just enjoy life for what it is, and he said it’s a hard process, it’s not, doesn’t something you can’t force it, it just happens.

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah. You get this idea, I love Richard Rohr’s work, I think he is influenced by Jung, right, and that’s a Jungian notion as well, that there’s a first half and a second half of adult life, and that certain ways of being, perhaps even certain forms of productivity geekhood, are maybe appropriate to young adulthood up to a point, but then they’re gonna stop being the answer, if they ever are the answer, and at that point, you do need to come up with a different way of thinking, one that isn’t entirely targeted on where you’re going. Some things people have said about this book in a semi-critical way, which I’m receptive to is that it’s a bit of a mid-life book, whether, I’m not sure I could have written it if I was in my 20s, I’ve tried very hard not to make it only appropriate to people in mid-life and I don’t think it is, but I think there are certain things you come to see just by being around long enough that certain methods and things you thought might work eventually that it’s like, “Oh, I’m never going to get to this summit that is implied in all these techniques that I’m pursuing, and if I’m not gonna get to it, maybe it’s time to think about a different approach.”

Brett McKay: So let’s go back to this idea of where you discover that the more efficient you got at doing in stuff, you felt you just, you started doing more stuff, and what’s interesting is half a century ago, there was an economist, I think, Maynard Keynes made this prediction, it’s like, “Oh, we’d only be working a few hours a week ’cause we’d be so productive and efficient.” But people are still working 40 hours a week or more, so what’s going on there? Why is it that we’re getting more done than ever, we’re more productive than ever, but we just feel like we have to work more to do more?

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah, it’s completely extraordinary, especially the way now that being incredibly successful in some professional sector is likely to leave you more busy than if you weren’t extremely successful, and you look at almost the whole of history, the whole point of being wealthy was so you could go hunting and have banquets or something, so you didn’t have to work all the time, and now that’s turned on it on its head. There are a huge number of different factors here, macroeconomic, social, cultural issues, but I think a very simple part of what we’re talking about here is just that if you focus on making any system such as your own personal productivity, any system, more efficient in the absence of some other guiding value just like efficiency for its own sake, then all else being equal, you’re gonna end up being busier and busier on less meaningful stuff because you just sort of create capacity that is then naturally filled by the pressures of the world, the pressures of capitalism, pressures of other people. If you get really, really good at processing your email as I know from bitter experience, you just get lots more email because you reply to things and that generate replies to those replies and etcetera, etcetera.

There’s this phrase, this saying, and if you want to get something done ask a busy person. The idea, if you’re really good at processing your work, you’re gonna get more work or take on more work, if you’re a sort of independent person who gets to, independently employed person that gets to choose, you’re still gonna choose to do more and more and more. And it’s exactly like when they widen freeways to try to ease congestion, like they add another lane to a freeway and then it makes that route more appealing to drivers, so more drivers are incentivized to use it and the congestion returns to what it was before. You get this sort of seems to work in all sorts of domains of life, this idea that just sort of becoming more productive will invite further inputs into the system. And the other thing I found was that they are less meaningful inputs because they don’t have to clear this hurdle. Someone says to you, “Can you do this?” And you don’t think to yourself, “Well, what am I going to neglect in favor of this?” You think, “Oh, just through becoming more efficient, I’ll be able to do it all.” And so you gradually end up taking on more and more and more things that you probably shouldn’t take on until the system is full of junk.

Brett McKay: And so how do you avoid that? Is it just a matter of having… In this instance, having a telos, like having… Here’s what I’m about, and if this task doesn’t fulfill that what I’m about, then that… It’s not coming on?

Oliver Burkeman: I think that’s a big part of it. Obviously, to the extent that this is a social and cultural-wide problem, it probably has to be addressed at a policy level too. But yeah, I think on a personal level, you can just see that you can bring yourself to see that you are not… To understand that you’re just not going to get everything done. Like you are in a situation where systematically it’s gonna feel like there’s more that really matters than you have the capacity to do. That this is built into the system, it’s not because you’re insufficiently self-disciplined or you haven’t found the right techniques yet, something like that.

And in that situation, once you internalize that understanding, it’s actually quite liberating because you can just sort of give up in a way, it’s a certain kind of surrender or defeat where you see that something you were trying to do was just impossible, but it’s a defeat that is the prelude to then being able to act with a much clearer head and more un-diluted energy and attention on a handful of things that matter ’cause you’re no longer attempting to do an impossible amount of things. You’ve sort of seen why it is that that is an impossible quest. It frees you up to focus on more things that do matter. And I think very simple strategies here include this… I spent a lot of my time as a productivity geek. You know, trying to trying to clear the decks. Trying to get to this situation where I would have dealt with all the little stuff. And I would have then these notional expanses of focus and time.

And it took me a long time to see that actually you can’t clear the decks because clearing the decks generates more work and more things come in onto the decks. And we live in a world of infinite stuff to come onto your decks anyway, so. At the most you can spend a couple of hours at the end of the day clearing the decks, sure. But you just at some point have to spend the first few hours on the thing you care about the most, even though the decks aren’t clear. And that is anxiety inducing, yes, it’s uncomfortable, but I think it’s the only way.

Brett McKay: And in one of your emails, you had this idea, instead of thinking of your to-do list as a bucket that you can empty, you just gotta think of it as a river, it’s just constantly… Stuff’s constantly gonna be flowing by and you just have to decide, is this what I’m gonna spend my time on the day or not, and maybe yes, but probably maybe you shouldn’t be spending your time on that.

Oliver Burkeman: Right, and the thing is that was always true anyway, right? It’s not like you’re suddenly deciding to let a bunch of people down. The point is this is baked into the situation, there’s all sorts of things that would have value if you did them that you’re never gonna do. So this is about being conscious of that situation so that you get to call the shots about which of the things you do do. Otherwise, in the words of workplace consultant Jim Benson, who I quote in the book, “You just become a limitless reservoir for other people’s demands and expectations,” because if you’re not making the decision about what to neglect in a situation where something must be neglected by definition, then somebody else is gonna make that decision and they’re gonna make it in their interests.

Brett McKay: And related to this idea of increased efficiency just encourages more stuff to be done, ’cause that’s what the system is designed for, just getting stuff done so it’s gonna continually want more stuff to do, is this idea of increased convenience makes us feel miserable, which is counter intuitive ’cause you think, “Well, if things are more convenient, if I can get stuff sent to my door directly from Amazon in a day, that should make my life easier.” But you make this case, yeah, maybe, but also maybe not.

Oliver Burkeman: Right. Convenience is such a great example of the perils of efficiency pursued for its own sake because… Yeah, I think in some sense, all the efficiencies of modern technology absolutely have made life easier. The question is whether easier is always what we want when trying to build the most valuable life. So a very simple example of that is, yeah, if you can… There’s a natural tenancy, if you can watch movies streaming at home and get food delivered to your door without ever speaking to a human being and do all the rest of this stuff, that’s easier than going out, meeting people or phoning a restaurant, talking to a human being. It’s easier but it sort of all adds up to something being taken out of life, which are these kind of rough edges and textures where you do have to speak to people and as a result, you sort of… It’s actually quite… It’s important for your well-being to have a few conversations with human beings in the course of your day.

I also give the example of, I’m in the UK right now, but for a long time I lived in the US with lots of family in the UK, always leaving it too late to send them a birthday card on time so I would end up using these online services where you put the card together with a photo and a message and then it prints it and mails it locally at the other end. And like everyone involved in that process knows that that’s not quite the same, that I’ve used convenience there and something is gone from the transaction, that if I had gone to the effort of planning with enough forethought, to have enough time go and buy a card, write in it, mail it, that would mean more to the recipient because actually something is lost in making that process really smooth and easy. So again and again, there are many examples of this I think… Yeah, it makes life smoother, but do you want a smooth life? I mean, to some extent you do, but maybe not a perfectly smooth one.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah, the Silicon Valley people who come up with these apps that make life convenient, they call those pain points friction, and their whole goal is to eliminate friction. And what you’re saying is, “No, actually friction can be good ’cause it allows you to talk to the clerk and you might have a conversation that you need that and it’s… “. I mean yeah, I don’t think you… A smooth life would be boring, so why eliminate it? Why eliminate friction?

Oliver Burkeman: Right. And you’re just sort of… Also you’re just sort of handing the decision about what kind of experiences you want in your life to a, other people in Silicon Valley designing this technology, and b, your sort of lowest impulses in a way, right, the impulse to not put in the effort to do something. And as philosophers, since ancient times, have understood that following your impulse all the time is its own kind of enslavement in a way, it’s its own kind of losing… Loss of autonomy. So yeah, just like if you can consciously integrate a few of these technologies into your life, I don’t… Certainly don’t think people should actively pursue only inconvenience at all points, but it’s just like handing the decision-making to forces that do not have your best interests at heart.

Brett McKay: So we have been talking kind of… About small ways that you can embrace finitude so you don’t feel so angst-ridden, but then you also talk about some… There’s a meta-cognition things you can do to help you think about time differently and your relation to time differently that if you do whether you meditate or not, if you do these sort of like, what do we call them… Mind games, we’ll call them mind games. It can help you think about your time differently, it can actually be really freeing and you get to just totally shift the paradigm. And one… There’s two things I wanna talk about, first is Heidegger’s concept of time, and there’s a reason why I saved Heidegger for last ’cause this guy… [chuckle] It’s hard to understand this guy. But I know you’re not gonna be able to exactly explain what Heidegger meant, and maybe we don’t even know what Heidegger meant [chuckle], but what’s Heidegger’s concept of time and how can that… Or your interpretation of what he thinks of time, and how can that change or how does that change your relation to time?

Oliver Burkeman: Yeah. Heidegger is not easy and I’m just gonna issue, as I always do, the caveat that I don’t claim that my interpretation is canonical or that somebody else wouldn’t want to offer a very different one. But my understanding of what Heidegger is saying, it is really something that points again to this idea that we were discussing in the context of medieval peasants, this idea that time need not be seen and is perhaps not best seen as this thing that is separate from us. That in a sense, our time and the fact that our time is finite, it’s not just like one of the traits that defines a human being, it is the fundamental one. Before we can ask any question about what we should do with our lives or how we should do it, we already find ourselves in this finite stretch of time, being born forward on the river of time. Perhaps we could say, as I think he sort of means to, that we just sort of are the stretch of time, it’s so fundamental but there isn’t really a separation. We just are a short stretch of time, being born forward towards death, we don’t know when it’s coming, every choice we make is a choice to not do other things, a million other things with that moment, that hour, that week.

And that there is a kind of choice that you have to make between doing all sorts of things to try to deny this feeling and not confront it and feel like you’re not in this situation of being born forward towards death in a stretch of finite time. Or facing up to it, facing up to the anxiety that that inevitably brings, but sort of taking seriously the stakes of your time and each moment of your time and what you do with your time. And so I think that that’s just a very useful shift to get into a little bit, I certainly don’t claim that I’ve done it perfectly, but I do think that there is something central to this idea of just seeing our situation for what it is and seeing how much effort we put into denying that our situation is what it is. And it’s not about… I don’t think it’s about spending your life in this sort of horrified awareness of death. I don’t think it’s really about death in that sense, I think it’s just about one major consequence of the fact that we die, which is that our time is finite and just letting the implications of that course through your veins a bit, to the point where you stop acting and making decisions as if you had all the time in the world. Not necessarily doing, trying really hard to do extraordinary things with every minute of the day, but just living in a sort of more authentic relationship to where you actually are.

Brett McKay: This section reminded me for some reason… I haven’t thought about this movie in years, but have you seen Tombstone, with…

Oliver Burkeman: I haven’t, I’m afraid.

Brett McKay: Okay. It’s a great movie. It’s the best movie about Wyatt Earp. The Wyatt Earp movie with Kevin Costner is really boring, I think so. This one, Tombstone, it’s a lot of fun. It’s got Val Kilmer, Kurt Russell, and there’s a scene… Val Kilmer plays Doc Holliday. He’s about to die. And he asks Wyatt Earp, he’s like, “What did you ever want?” And then Wyatt Earp says, “Just to live a normal life.” And Doc Holliday said, “There’s no normal life, Wyatt. It’s just life. Get on with it.” Yeah, so I think we had some Heidegger in Tombstone, I think so in there.

Oliver Burkeman: [chuckle] Yeah, no, I think that’s… Yeah, I can see the connection. I must watch that movie.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Or you can at least watch the scene, you can look it up on YouTube. So the final thing that you do is you talk about… It’s like a mind, a meditation you had to do, it’s called Cosmic Insignificance Therapy. How can this help us feel better about our time management, or have a more humane approach towards time management?

Oliver Burkeman: I mean, this is my slightly facetious label for the process of really putting some effort into imagining, understanding how tiny and insignificant… Yes, you are, considered… Not you personally. You know, how [chuckle] insignificant we are considered in the sort of expanse of the history and the future of the cosmos. I think there’s something just at first glance incredibly freeing about understanding that the way you get sort of paralyzed by the seeming significance of choices you make, it can be very relaxing right away and I think motivating to understand that a thousand years from now, a hundred years from now, almost nothing you decide is going to matter in any way, that can actually be an invitation to just sort of take some risks and live boldly and do some things that you wanted to do without being so anxious about their impact.

I also think that it’s a really useful way to consider and reconsider the definition of a meaningful life that you’re sort of implicitly carrying with you when you assess your own life and try to build a meaningful life. The obvious criticism of this approach, I get it, right, is that it’s just like, “Well, if everything is so point… If we’re all so insignificant, why do anything? It’s all pointless.” But I just don’t think that that follows. I write in the book about the work of a philosopher Iddo Landau, who points out that the person who says, “Well, nothing I do is gonna count for anything in a thousand years time, or probably won’t have… So why do anything?” They are invoking, whether they recognize it or not, a definition of a meaningful life that is set, where the bar is set so high that they would have to sort of be superhuman to meet it, they would have to manage to, if not be superhuman, then at least reach the level of the kind of person who occurs once in several hundred years, a Shakespeare or a Tolstoy or a Michaelangelo.

And that we should question whether we really want to be going around with this kind of definition of what makes it worth doing things and what is meaningful. We should consider that there are all sorts of kind of ordinary seeming things that could absolutely count as the content of a meaningful life, that… Do you really wanna say that working for an organization that makes your small neighborhood a little more beautiful or a little friendlier, that that was pointless because it didn’t affect the whole planet forever? Or that caring for an elderly relative who needs that at that point in their lives is kind of pointless because you didn’t put a dent in the universe? I think that most of us intuitively know that we don’t want that kind of definition of what counts as a meaningful life, and we do want to remember that ordinary things can be meaningful.

Or on the low… I think about this book, like if it affects a few people positively in my generation, that’s great, it should not be the measure of a book that you write that in hundreds and hundreds of years’ time, people are celebrating it, like that, that’s just… Why adopt a level of a definition of meaning that sort of systematically puts almost everything that we do as humans on the wrong side of it?

Brett McKay: Well, Kierkegaard talks about that. He has that quote, it’s like, “The ambitious man whose slogan is “either Caesar or nothing”, and then he doesn’t become Caesar, and he just becomes, he’s in despair. He’s like, “Well, nothing matters.” And Kierkegaard is like, “That’s dumb. Don’t do that, that’s stupid.”

Oliver Burkeman: Right.

Brett McKay: And yeah, and this chapter reminded me of my great-grandfather in his memoir, at the end of it… He wrote this like in the ’50s or ’60s, he put at the end of his memoir a poem called There Is No Indispensable Man. I’ll link to it, but it’s the same sort of thing. It’s like, you come into this world, you might make a big splash, but when you leave it, you’re not gonna leave much behind, but that’s okay. And for some reason, I find it, ennobling. And it’s like, yeah, I’m gonna take risks. I’m gonna do, just find meaning in my mundane everyday life, that’s okay. It’s probably the best we can do.

Oliver Burkeman: Right. And I really don’t think it’s a counsel of despair. I don’t think it means that you have to have a less meaningful life, I don’t think it means you can’t do extraordinary things or things that will lead to you achieving fame and fortune. I think that’s all great. I just think that when you’re considering the ways you’re spending your life, that it shouldn’t be the… The criterion should not be something sort of… That is kind of superhuman in that regard. If you do something that counts and it gets you a lot of fame and fortune, great, I’m not against that at all, but don’t use that as… Let alone these kind of even bigger kind of cosmic level kinds of definitions of meaning, don’t use all that to define what counts as meaningful. Follow something more human. And then if it’s successful, maybe fame and fortune will follow.

Brett McKay: And then you can apply this to your to-do list. Don’t think you have to have on your bucket list, “write a New York Times bestselling novel”. If that happens, great, but write the book that you’ve been wanting to write for a long time, even if it’s crappy, and even if no one ever reads it. Just write the book.

Oliver Burkeman: Right. Yeah, I mean, if it matters, it matters, it shouldn’t need to matter on the level that is sort of something that’s entirely beyond human control or your control. Right, exactly.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, Oliver, this has been a great conversation. I’ve had a lot of fun. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Oliver Burkeman: You can pick up the book anyway you would expect to be able to pick up books, and then my website is oliverburkeman.com where you can also subscribe to my email newsletter, which I call The Imperfectionist.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Oliver Burkeman, thanks for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Oliver Burkeman: Thank you, I’ve really enjoyed it.

Brett McKay: So when I was talking to Oliver about cosmic insignificance therapy, I mentioned a poem called There Is No Indispensable Man that my great-grandfather, William M. Hurst, included at the very end of his memoirs that he published shortly before he died. I also learned that General Dwight D. Eisenhower carried a copy of this poem in his pocket at all times, I’m guessing it was his way of doing some cosmic insignificance therapy. So for your enjoyment and meditation, here’s the poem, There Is No Indispensable Man.

“Sometime when you’re feeling important, sometime when your ego’s in bloom, sometime when you take it for granted, you’re the best qualified in the room. Sometime when you feel that your going would leave an unfillable hole, just follow these simple instructions, and see how they humble your soul. Take a bucket and fill it with water, put your hand in it up to the wrist, pull it out and the hole that’s remaining, is a measure of how much you’ll be missed. You can splash all you wish when you enter, you may stir up the water galore, but stop, and you’ll find that in no time, it looks quite the same as before. The moral of this quaint example, is to do just the best that you can, be proud of yourself but remember, there’s no indispensable man.”

My guest today was Oliver Burkeman, he’s the author of the book, Four Thousand Weeks. It’s available on Amazon.com and book stores everywhere. You’ll find more information about his work at his website oliverburkeman.com, also check at our show notes at aom.is/fourthousandweeks where you can find links to resources where we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM Podcast. Make sure to check at our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of, and if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding everyone listening to AOM podcast, to put what you’ve heard into action.