Show Highlights

- Why Neil Armstrong thought Apollo 8 was a more important mission than his own Apollo 11

- A brief overview of the Space Race between the US and the Soviet Union

- Why JFK’s moonshot announcement took NASA by surprise

- Why the US was so far behind the Soviets at the beginning of the Space Race

- The genesis of NASA’s Apollo program, and how it almost came crashing down after Apollo 1

- The most powerful machine ever built

- The crazy, insane, risky challenge of making Apollo 8 work

- The 3 brilliant, courageous men who were tasked with manning Apollo 8

- The importance and resilience of these men’s wives and families

- Why the Soviets didn’t beat the US to the moon

- What the men of Apollo 8 said to the world on Christmas Eve 1968

- What Apollo 8’s success meant to America and the world in the turbulent atmosphere of 1968

- The lessons Robert took away in studying and writing about these men

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- My first podcast with Robert about pirates

- Henry Crown Space Center

- JFK’s 1961 moonshot announcement

- NASA’s Mercury and Gemini programs

- Apollo 1

- Frank Borman

- Jim Lovell

- Bill Anders

- Saturn V (and Cronkite’s awe over the machine)

- Apollo 8 launch broadcast

- Apollo 8 Christmas Eve broadcast

- Earthrise photo

Connect With Robert

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

LifeProof Backpacks. LifeProof backpacks are packed with smart features to thrive in all conditions. Get a 15% discount by visiting lifeproof.com/manliness.

The Great Courses Plus. Better yourself this year by learning new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to The Great Courses Plus. Get one month free by visiting thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Starbucks Doubleshot. The refrigerated, energy coffee drink to get you from point A to point done. Available in six delicious flavors. Find it at your local convenience store.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Now when you think of the Apollo program, the first thing that probably comes to mind is Apollo 11 and Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepping foot on the moon. But even Armstrong didn’t think his moon landing was the most important or even daring of all the Apollo missions. For Armstrong, Apollo 8 best fits that description.

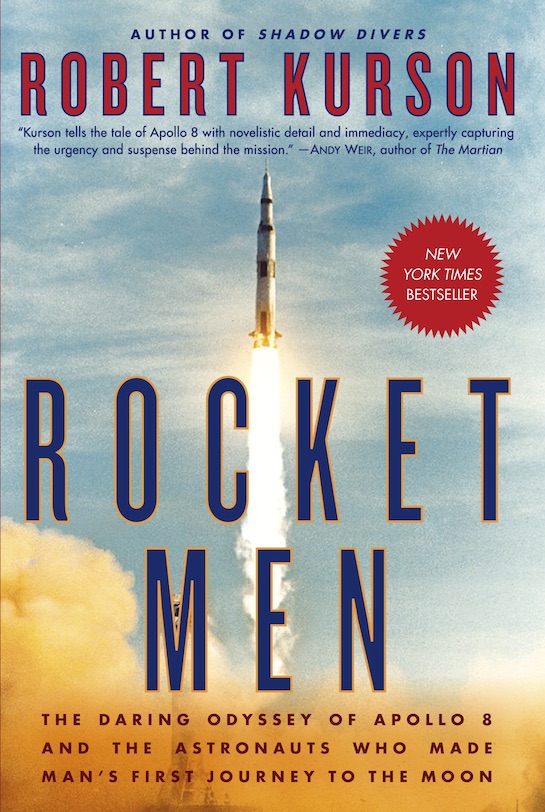

If you’re like most people, you probably know very little about Apollo 8, let alone the names of the three astronauts who flew on that mission. But after today’s episode, that’s definitely going to change. In fact, you’ll likely never forget their stories. My guest on the show today is Robert Kurson, who’s out with a new book called “Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man’s First Journey to the Moon”.

We begin our conversation discussing the state of America’s space program before John F. Kennedy made his famous “moonshot” speech in 1961 and why the Soviets kept beating America in the Space Race. We then discuss the audacious and near impossible plan made in just a few hours, in August 1968, to put men into orbit around the Moon by Christmas of that year. Robert then tells about the lives of the three men who would be the first humans to leave Earth’s orbit and the first to orbit the Moon, and why they were the perfect astronauts for this mission. We also discuss the role the wives of these astronauts played, and why out of all the married astronauts who took part in the Apollo program, the astronauts of Apollo 8 were the only ones that never divorced.

We end our conversation discussing the climatic speech the astronauts made on Christmas Eve from the moon and the life lessons Robert learned from writing about and talking with the men of Apollo 8. This is an inspiring and truly poignant episode. After it’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/rocketmen. Robert joins me now via clearcast.io.

Robert Kurson, welcome back to the show.

Robert Kurson: I’m so honored to be back. Thank you so much for having me.

Brett McKay: So we had you on the show a couple years ago to talk about your book “Pirate Hunters”, which is, if you haven’t, if folks haven’t listened to that podcast, listen to it and then go buy the book. The book’s fantastic. You’ve got a new book out. Instead of the seas of the earth, it’s about the seas of outer space. It’s called “Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man’s First Journey to the Moon”.

Just like “Pirate Hunters”, this book, it read like a movie. Like I was imagining a movie like Apollo 13 as I was reading this. It was so good. I’m curious, what led you to this, from talking about pirate hunters, people looking for lost pirate ships, to talking about the first manned mission to the moon?

Robert Kurson: This was just a real happy accident for me. And you know, the older I get, the more I realize how dependent we are on luck and good fortune. It’s kind of an unnerving thought, actually. But what happened to me was, I was at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, which is my hometown, and I was showing some friends there the U-505. It’s one of only five U-boats that remain the world. And it happens to be an exact match for the U-boat I wrote about in my first book “Shadow Divers”.

And so showing the friends around, and then said goodbye, and I tried to find my way out of the museum. And one of the real nice features of the museum is it’s so giant and so complex. It’s very hard to find your way out. It’s kind of fun, actually. But I turned left instead of right, or maybe it was right instead of left, and I found myself in the Henry Crown Space Center. And there in the middle of the Space Center was a spacecraft that looked at once to have come from the past and the future.

It was scarred from it’s journey, wherever it had gone. I had no idea what it was, so I went up and I read the placard. And it said, “This is the command module of Apollo 8,” which was man’s first journey to the moon. And I was shocked at that because I fancied myself someone loved space and astronauts. I certainly paid rapt attention when I was a grade-schooler, when Apollo was being shown in our classrooms. Had no idea what Apollo 8 was or that it was man’s first journey to the moon.

So I went home, and I did, I started doing some research. And within, I’d say, 15 or 20 minutes, I knew that I was reading about the single greatest space story ever. It was so incredible and full of so much risk and daring and bravery and huge importance I could hardly believe it. But I wasn’t the only one. Astronaut after astronaut that I listened to and read about felt the same. And that was true especially of Neil Armstrong, who happened to be on the backup crew for Apollo 8.

But when Neil Armstrong spoke about Apollo 8, he did it with a reverence in his voice that he didn’t even seem to use for his own Apollo 11 mission. “Everything about Apollo 8,” he said, “was for the first time.” He said, “By the time we went on Apollo 11, much of what we needed to do had been proven doable. But when Apollo 8 went, nobody knew that any of it could be done.” And one after another of the NASA Apollo astronauts and the NASA managers and legends spoke about Apollo 8 that same way, in a different way they spoke, it seemed to me at least, about anything else.

And when I started to read more and more about what was required and the daring that was required and why they did it and how they did it, I thought, “This is, not just in my mind, the single greatest space story of all time. It’s one of the great stories in the history of human exploration.”

Brett McKay: No, I completely agree. I was the same way. I knew about Apollo 11. I knew about Apollo 13 thanks to Tom Hanks. Knew nothing about Apollo 8. And then after I read this story, I was like, “This is the most amazing story that more people need to know about.” So, for people to understand why this was such a big deal, let’s get some background. What was the state of the U.S. space program before Apollo 8, and I guess before Kennedy came in and gave his “moonshot” speech?

Robert Kurson: Well the Space Race that we talk about, which is this existential battle between the United States and the Soviet Union for control of outer space. And there were huge military implications in it, as well as implications about which country’s science and technology was better. In fact, which country’s politics and way of life was better. It was very much focused on the Space Race.

That began in about 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, into orbit. And for a couple days, it seemed a miracle. People in the United States loved it, that there was this artificial satellite. You could actually listen to it on shortwave radio, and if you had good binoculars or even good eyes, you could see in the sky and they could tell you exactly where it would’ve been.

But after a couple days, it sunk in to the American people and the American politicians just how dangerous this was. If the Soviet Union could put an artificial satellite wherever it wanted around the Earth, they could also drop bombs or even put soldiers in space from wherever they wanted. And that really began the Space Race. And for several years, the Soviets seemed way ahead of us, which was almost unbelievable. They could hardly build a good car at the time, they’d suffered devastating losses in World War II, and yet here they were ahead of us in the most complicated and important technology in the world. And they just seemed to keep beating us and beating us.

They got the first man into, not just into space, but into orbit. The first dog, the first woman into space. It was just one victory after another for the Soviets. And by 1961, President Kennedy realized that America needed to do something, not just great, but nearly impossible, to overtake the Soviets. But we were so far behind at the time, he needed to do something that was far enough out in the future that it was possible that we might catch up to them.

And the idea became, and he made this announcement in 1961, that by the end of the decade, the United States would land a man on the moon and bring him home safely. And the announcement stunned Congress. I mean, you could hear it. If you listen to the broadcasts or watch it on YouTube, there’s like silence when he says it. It’s so outrageous and so impossible, people couldn’t believe what they were hearing. But that was true also of the NASA managers. When I spoke to them and they told me about hearing it, they said, “What’s he talking about? We have no idea how to do that.”

Nonetheless, the President made that promise in 1961, with the idea that we needed to do something so spectacular and so almost impossible that it would overtake the Soviet Union and prove to the world, not just that we could control space, which was essential in the modern age of nuclear weapons and everything, but that our system of government and of life was superior to theirs. So that’s really when it started. And we really were way behind at that point.

Brett McKay: Why were we way behind? Because I mean, as you said, like the Soviet Union could barely put together a good car. Like we developed the nuclear bomb first, nuclear technology. What were the Russians doing, or the Soviet Union, what were they doing that we weren’t doing?

Robert Kurson: Well, I think they were not as certain as we were that they were going to be ahead, so they were working very, very furiously. But they were also taking huge risks, and that’s something I don’t think we understood quite at the time. Even though they kept doing these space spectaculars and doing these, one first after another after another in space, they also were taking the kinds of risk that the United States was not willing to take. We didn’t know that at the time, so it seemed baffling why they should be so far ahead.

And they also had brilliant scientists. Rocket scientists and other experts who were giving everything they could, and they devoted a huge amount of their budget to the space program because they viewed it as we did, as an existential proposition. That the country that could control space ultimately could control the military and possibly the world. So it was very important to them and they were willing to risk whatever it took to get them there.

Brett McKay: Okay, so Kennedy makes the “moonshot” speech. What had, what did NASA have to do to make that happen? I mean, they couldn’t just immediately go put someone on the moon. They had to do this in stages so they can learn things. So what was their first goal as part of the Apollo program?

Robert Kurson: Well they first had to figure out how to get to the moon. You know, trajectory calculations. They had to build software and computers to do it. I mean, we could go on for hours and hours about the technical requirements. The most interesting thing to me, though, when I asked those questions of people at NASA was their answer that, “We really didn’t know how to do much of any of this. We had eight and a half years and we had to really go figure it out.”

And at that time, it looked like the Soviets were way ahead of us in the idea of getting a man on the moon. And that was really the end goal of the Space Race. It was really kind of believed on both sides that the country that could land a man on the moon first and bring him back safely really had just about won the Space Race. So all kinds of things had to happen. And when I asked some of these legends at NASA, “What did you need to do first?”, they just laughed and they said, “We needed to do everything.”

Brett McKay: So I mean at this point, before the “moonshot” speech, the Gemini program had been in. This is like men orbiting the Earth, right? That had already happened?

Robert Kurson: Well, no. Mercury was first. Gemini is where we really started to catch up to the Soviets. We were behind for years, but Gemini, which is really the program, “We’re going to learn how to do a lot of the things that need to be done on lunar flights.” That’s when that’s perfected. And that’s when the tides really start to turn in the Americans’ battle against the Soviets in space.

Brett McKay: What year was this, about?

Robert Kurson: Well you’re looking at, when we’re talking about Apollo 8, we’re talking about 1968. So up to about 1967, late 1966, that’s when Gemini is going. And that’s when we overtake the Soviets and it looks pretty good for us at that point.

Brett McKay: Alright. So let’s talk about Apollo 1, which was the first mission, part of the Apollo program. What was its mission, and then what happened to that flight?

Robert Kurson: Right. So the Apollo program itself is the program that’s going to land, deliver men to the moon, land them on the moon, and bring them back. So Apollo 1 is scheduled to be the first manned flight of the Apollo program and it’s supposed to be a low Earth orbital test of the command and service modules. To land a man on the moon, you need three modules. You need the command module, which is where the astronauts exist and live and operate. The service module, which is where, the home to all the technology and electronics, or much of it. And then you have a lunar module, which is for the landing part.

Apollo 1 is supposed to go without the lunar module and is supposed to just test out the command and service modules in a low Earth orbit. And that’s planned for January, or early, or maybe it’s planned for February of 1967. But in January, late January of 1967, they’re doing a test. Just a test, they’re not going to launch the launch pad. And there’s a disaster. There’s a fire in the cockpit in the command module. And the three astronauts perish in the accident. It’s a terrible, awful accident. There’s recordings of the astronauts struggling. It’s a terrible thing to listen to and to think about. But it as a disaster at the very moment when it looked like we were really going to take the lead and perhaps this Space Race.

Brett McKay: And then how did that affect NASA and everyone involved with this program?

Robert Kurson: Well it was a grave threat, not just to the Apollo program, but perhaps to NASA itself. There were Congressional investigations, and many people worried for the very existence of the American space program.

NASA launched a huge investigation into the causes of the accident. And the primary astronaut they put in charge of investigating and also fixing the problems was Frank Borman, who was considered one of the finest astronauts NASA had. And Frank Borman was the first astronaut inside, who went inside the charred remains of the Apollo 1 command module. But he also was sent by NASA to speak to Congress, and he did it in a very direct, very no-nonsense way. He even was stern with them and told them, “Let’s stop the witch-hunt and get on with this. We have faith in ourselves. Do you have faith in us?”

And there seemed, there wasn’t a person at NASA, from the astronauts down to the janitors who cleaned up at night, who didn’t cheer him on. Borman was so widely respected and such a serious, no-nonsense person. He was the perfect person to put before Congress. And despite the objections of some in Congress, NASA was allowed to continue and the Apollo program was allowed to continue. So it was kind of a narrow escape. It was a terrible disaster and things had to be redesigned, but Apollo was still alive at that point.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean there was a lot of debate going on then that you’re seeing now. Like, you know, today you’re seeing like, “Well there’s no point in putting humans on the moon because we can just send robots to do that.” People were saying that too, it’s like, “What’s the point of putting humans, when we can send some sort of robot to do that for us?”

Robert Kurson: Right. And they also made the argument that it was extraordinarily expensive and extraordinarily dangerous. And the disaster with Apollo 1 on its test was just proof to many of these people that this was just too dangerous a proposition for a civilized country. But there was so much to be gained by doing it and so much to prove, no just to your own country, but to humanity. This was probably the single hardest thing human beings would ever try.

And so there was something in American DNA, I believe, and in human DNA, that pushes us to explore, and especially to explore the unknown, and maybe the unreachable. And so Apollo was still going. And certainly the Soviets were still going. And there was good arguments to be made, that you could not allow your existential enemy, the only other superpower in the world, to beat you onto what many believed was the ultimate battlefield in the universe, outer space.

Brett McKay: Okay. So we’ll talk about Frank Borman here in detail a bit because this guy is a true American badass. Like I, this is like my, one of my new heroes now after learning about him. So Apollo 1, the disaster happened, he goes before Congress, saves NASA basically. What happened after that? Did they, what was the next mission? And what was, where were the Russians at in their race to the moon at this point?

Robert Kurson: Well the Russians look like they are really doing great. They are sending, in the process of sending unmanned but human-size spacecraft around the moon. Not landing on the moon, but they’re reading to send missions around the moon in preparation for a manned flight. And in the meantime, NASA has to test the Saturn V rocket. It’s the only machine powerful enough to deliver human beings to the moon. By the way, think about this as we sit here in 2018. To this day, 50 years later, a Saturn V rocket is still the most powerful machine ever built by humans. 50 years later. Think about, technology’s obsolete in months sometimes now. 50 years later, this rocket is still the most powerful machine ever built.

But they needed to test it. It had never flown before. And so it was tested first on Apollo 4, unmanned, just the rocket, and had a very good success. Wonderful to listen to Walter Cronkite’s description of it on YouTube, by the way. He’s just overwhelmed by the majesty and the sheer power of the thing. But Apollo 6 is its next test. And that fails spectacularly. That’s only the second test of the Saturn V, but it has got huge problems. And so that’s just another issue for the Apollo program.

In the meantime, the Soviets look like they’re getting closer and closer to sending a human around the moon. They’re not ready to land, and nor are we in 1968, but they’re getting close to getting the first men to the moon. And that, in the minds of many people at NASA, would be nothing short of a disaster.

Brett McKay: Alright, so Apollo 6, disaster. Didn’t go as planned. But then someone has this cockamamie idea, “We’re going to put a man around the moon in four months.” So tell, and this is going to be Apollo 8. So what was the origin of that plan? How’d that all happen?

Robert Kurson: Well here’s what happening. In August of 1968, in early August, there’s a very big problem at NASA, and the problem is with the lunar module. That’s the spidery landing craft that two of the three astronauts are going to ride from the orbiting command module down the surface of the moon and back up to the orbiting command module. That’s what you need to land men on the moon. But problems in production and design have caused the lunar module to fall way behind schedule. And that means Apollo is falling way behind schedule.

At the very same time, a top secret memo comes in from the CIA, warning NASA that the Soviet Union looks ready to send the first men in history around the moon as early as late 1968. So NASA has a very big problem on its hands. If the lunar module is plagued by design and production problems and is slowing everything down, that means Apollo is slowing down, which is very expensive, and they have to wait for this thing. It means that President Kennedy’s promise to the nation is in severe jeopardy, because if they can’t test this lunar module and get it going, they’re never going to land men on the moon by the end of the decade. And it means that the Soviet Union looks primed to get the first men around the moon.

And there’s a brilliant, brilliant man named George Low, who’s in charge of the Apollo spacecraft, who’s thinking about these problems nonstop in the summer of 1968. And in early August of that year, he has an epiphany. It’s one of the most brilliant insights, I think, that’s every occurred at NASA. He thinks, “Why don’t we, instead of waiting for the lunar module to be ready and just standing down, why don’t we send Apollo 8,” which was really just scheduled to be a low Earth orbital test of the command and service modules, “Why don’t we send that all the way to the moon?” And not just around the moon, like the Soviet Union is planning to do, but in orbit around the moon, which is magnitudes more complicated.

It seemed a perfect plan. It meant that they did not have to wait for the lunar module. But if they could send a crew around the moon, they would learn so much about what it took to go to the moon, except for the landing itself, but they would learn everything about the trajectories, about how the software worked, communications between the spacecraft and Earth, and so much more. So much about the lunar mission itself could be learned. They could scout landing sites for the future first landing, and all kinds of other things. They could get that all done without stalling the program. They could keep President Kennedy’s promise alive.

And they’d have an outside shot, if they went in late December, of beating the Soviets to the moon and getting the first men to the moon, ever. So in that respect it seemed like this brilliant insight, a real epiphany. The problem was, it would require huge risk. The kind NASA had never even contemplated before. The mission would have to be planned, trained for, and executed in four months’ time. Not the usual 12 to 18 months that a space mission took for planning and training, but just four months. They would have to fly the Saturn V rocket in only it’s third flight.

And remember, in just it’s second test flight. It had failed spectacularly. But this time it would be going with three men who had families, wives and children. And it wouldn’t be going just into low Earth orbit, 100 miles over the Earth, or even 853 miles above Earth, which at the time was the world altitude record. It would be going 240,000 miles away to the moon, to this ancient companion that had called to human beings for eternity. And it would be going without the lunar module.

Now remember, they weren’t planning to land Apollo 8, but the lunar module served a secondary function, and that was as a backup engine in case the primary engine at the moon failed. That meant if Apollo 8 went into orbit and that primary engine didn’t fire or it fired improperly or anything went wrong, the astronauts would crash into the lunar surface or fly off into solar eternal orbit or any other number of fatal results. That one engine had to work perfectly or they weren’t coming home.

And then there were all kinds of other risks in the idea that we weren’t ready to do it yet. NASA had to build software very quickly. They had to calculate the trajectories. Everything had to be rushed and compressed into this very tiny timeframe. But if they could do it, if they could really pull off a miracle, to do something close to impossible, they could keep President Kennedy’s promise alive, keep the Apollo program moving, and they had this outside chance to become the first human beings ever to reach the moon, and to really beat the Soviets in the Space Race.

And it was decided right there in very early August by George Low and then Chris Kraft, who was another legend at NASA and the mastermind of Mission Control, it was decided in a matter of minutes basically, maybe a couple hours, “This is what we’re going to do,” and the plan was off and running. Now they had to find a crew.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean that’s … I think people need to understand, like there’s so much they had to do, they’ve never done it before. They had to do it in four months, and they had to do it perfectly the first time, without ever having any practice runs, really, like in real life. That’s what makes it so crazy.

Robert Kurson: And that’s what Neil Armstrong spoke about when you hear him doing interviews. Like everything they did, everything NASA did was for the first time. And it was just, almost unthinkable that they could do it so fast and so suddenly, and yet they all committed to do it.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s, to me, like that moment, like super-inspiring. I mean, it’s just like, it’s just the moxie, the guts, the grit, that … I mean it just, it’s super-inspiring that we had that at one time and people just like weren’t-

Robert Kurson: Yeah, and breadth … And think about this. When they went, when Low and the others went to the head of NASA, James Webb, with the plan and explained it to him as, “We just discussed it ourselves.” Webb heard them through. He was in Vienna at a conference, and they called him on a secure line because they couldn’t afford to have the Soviets pick up on any of this. Webb heard out this plan and he said, “Are you out of your minds?” And he went through the risks and the challenges, the impossibility of the whole thing.

But then he reminded them of something they hadn’t considered. He said, “If anything happens to these three men, no one, lovers, poets, no one, will ever look at the moon the same way again.” But that was also true of Christmas, before Low and Kraft’s plan called for Apollo 8 to be in lunar orbit on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day of 1968. So if anything happened, no one’s going to look at the moon or Christmas the same way again. It could not have been riskier.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that point was really … I never thought about that, but it’s true. If this mission failed, the next time you look up at the moon, you would just think, “There’s three guys dead floating around the moon.” So this had to be a success or it would just ruin the romance of the moon.

Alright, so you say, okay, they got this plan, they got to come with the crew. Let’s talk about the crew here. First person, the Commander of this mission, was the guy who was the investigator of the Apollo 1 disaster, Frank Borman. Tell us about Frank Borman, because I never knew, I didn’t know anything about this guy. But after reading about it, I was like, “Man, this guy … He’s awesome.” So tell us about Frank.

Robert Kurson: He really is awesome. He was universally respected by his fellow astronauts and by all the NASA managers. Not everyone like him equally, but everyone respected him profoundly. He was a completely no-nonsense, all business kind of person. Well most of the astronauts drove sports cars, a lot of Corvettes. Borman drove an old pickup truck. He didn’t go in for any of the fast living that any of the astronauts did. He was there for a single reason, one reason only, and that was to beat the Soviets to the moon. He was a true Cold Warrior, and his only interest in being at NASA was to fight the Cold War on the ultimate battlefield, outer space. And that’s where he believed he could do the most good.

He had very little interest in exploration or the romance of the moon. He was there to protect America, which he believed was the greatest country in the world, loved America. And to defeat the Soviet Union, America’s greatest threat. And so that’s why he was an astronaut. He, as I said, commanded the respect of everybody. And he was training to be the Commander of Apollo 9. But when it came time to change Apollo 8’s mission, they called Frank Borman in from California, where he was working to improve the command module, and laid it out for him very clearly.

They said, “Frank, we have a top secret memo from the CIA warning that the Soviet Union can make it to the moon with men before the end of the year. Do you want to go to the moon?” And without consulting his wife or his family or even his two crew-mates, Borman said, “We’ll go.” And that’s how it started.

Brett McKay: That’s how it started. I love that. So next guy was Jim Lovell, and if people have seen “Apollo 13”, they know about this guy. But why was Jim picked to be part of this mission?

Robert Kurson: Well Lovell was part of the, Borman’s crew. He had replaced Mike Collins, who would ultimately end up on Apollo 11 when Mike Collins had a medical problem. So Lovell had been working with Borman’s crew, and he was kind of the polar opposite of Borman. He was as nice and warm and friendly a guy as you could ever meet. By the way, Borman is as nice and friendly and warm a guy as you could ever meet, you just got to get to know him. But on the outside, Lovell was very warm and approachable and universally really loved by his fellow astronauts and the people at NASA.

He had grown up, very poor kid, in Milwaukee. He’d lost his dad in a car accident very early on. Grew up really poor in Milwaukee. But he, unlike Borman, always had dreamed of space, at least since he was in high school, I should say. He was mesmerized by rockets and the idea of space travel and pushing into the unknown and exploring. And he had even built and launched a rocket in high school. He had wrote his thesis at the Naval Academy, not on ancient battle tactics or dry subjects like that, but about the possibilities of rocket travel in space.

And so you would’ve thought that Borman and Lovell maybe could not have been more opposite. And yet they had been paired together on Gemini 7, which was a two-week, believe it or not, 14-day mission in a capsule no larger than the front half of a Volkswagen Beetle. They spent 14 days together. And even though they seemed different from each other, they could not have meshed better. They got along beautifully. They sang together. They really like each other. I’d go so far as to say they loved each other.

And when they splashed down and finally came out after this 14 days on the recovery ship, Lovell said, “I’d like to announce our engagement.” So, and no one laughed harder at that than Borman. So they had flown together in space before, longest space mission ever, manned space mission. And so they were naturals together. And then they had a third crew member, who seemed to be this uncanny combination of the both of them. He was, name was Bill Anders. He was younger than Lovell and Borman by five years, and had never made a space flight before.

But he loved the science of it. He loved the idea of exploration, but he was also a true believer in the Cold War and the importance of America’s mission in beating the Soviets and understood that to be the true purpose of this push to the moon. And so this crew really had meshed so beautifully. And when Borman was called in that day, he knew that his crew would be read to go. And so he answered for them, and indeed they were ready.

Brett McKay: Another thing I think that we need to point out, is oftentimes when we think about these astronaut, thinking of sort of like these risk-taking guys, you know, riding, driving Corvettes, fighter pilots. A lot of them were fighter pilots or test pilots. But the other thing that you forget, like these guys were incredibly, incredibly smart. I mean they had advanced degrees, rocketry, nuclear physics, et cetera. I mean they were like the whole, complete package.

Robert Kurson: They were. They’re almost impossible to believe how well-rounded they were. Anders was a nuclear engineer. Borman held his own against the top science students in the world when he was getting his Master’s, and same for Lovell. So these guys were as smart as they were brilliant pilots. They really were the best of the best. There is no other way to say it than to say they had the right stuff. They really did.

But the thing that impressed me most, and you know, I worked with all three of these guys in person for countless hours writing the book and got to know them really well and their families. The thing that struck me most was just what regular guys they were because when you read about them and how accomplished they were academically and in airplanes and in spacecraft, they seem almost of a different species. But at least for these three guys, Borman, Lovell, and Anders, I don’t know that I’ve met three nicer, more regular guys.

I think NASA just really, really knew what it was doing when they picked these early astronauts.

Brett McKay: So not only, you talk about what’s going on with these men, we’ll talk about their mission here in a bit, but their wives. Each of, all of them were married. None of them were bachelors, they all had families. But their wives played a big role in this story as well. So I mean tell us about these women. You know, there’s always that phrase, “Behind every strong man or important man, there’s a strong woman.” So I mean in this case it really was true with these three guys.

Robert Kurson: It was so true, and something that I’m a little ashamed to say I didn’t really expect going in. I was so focused on the flight itself and the astronauts themselves that it didn’t occur to me how important these women were. But it took me all of a few minutes on the presence of each of these men to realize that their wives were every bit as important to the flight of Apollo 8, every bit as courageous, and every bit as heroic. Without them, I don’t think this would’ve happened.

These women endured incredible stress. They knew that on any given moment, and they knew this back into the test pilot and fighter pilot days, that a black car could pull up to their driveway and give them some terrible news. It happened to their friends all the time. But the idea that these three would be the first ever to go to the moon was extremely stressful, especially on Susan Borman.

Susan Borman had been very close friends with Pat White, who was the wife of Ed White, one of the three astronauts who perished aboard the Apollo 1 test. And Susan saw what the tragedy had done to her friend Pat White, who had started to drink and whose life began to fall apart. And when Susan saw that and had endured already so much stress from watching Frank in a very high-stress and high-risk occupation, she started to drink a bit herself and then a bit more and even more.

When Frank came home that day and told her about the change in mission and that he would be commanding the first manned flight ever to the moon, she smiled and hugged him and told him how proud she was, how much she loved him. And then she went into another room and when Frank was out of earshot, she kicked the door over and over, and was dying inside. She felt certain from that moment forward, and I mean certain, not probably, not more likely than not, but certain that Frank was going to die aboard the mission.

But Susan, like many of the other astronaut wives, considered it her duty, not just to her husband, but to her country, never to betray the stress she was under, never to show husband a moment’s doubt about the security of his home. His job was to pay attention to flying the spacecraft and her job was to make his home as stress-free as possible. So Frank had no idea of the suffering Susan was enduring and really started to endure when this mission became a lunar one.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean that was the big point that hit home to me, that you did a good job, is all three women … It wasn’t just about, “Oh, this is so great my husband’s doing this,” or like it’s a, or, “I’m afraid for my husband.” They all three of them, like these three guys, that had, it was very mission-oriented. It was something bigger than themselves. And that they were behind it 100% because it was a way we could defeat that existential threat of the Soviets.

Robert Kurson: Exactly. And they also believed in it because their husbands believed in it. It was important to their husbands and it was important to them. And so they made very happy homes for their husbands and trusted that their husbands knew what they were doing. Marilyn Lovell and Valerie Anders believed that things were going to be okay. Susan did not. Although, it’s so interesting, when Bill Anders came home that night and told Valerie about it, she asked, “What do you think the chances are of success?” And Bill knew that Valerie didn’t want to hear any BS and he never BS’d with her anyway.

And so he thought about and he calculated it and he said, “I think, these are the odds of success for Apollo 8. I think there’s a one-third chance that we come home and have a successful mission. There’s a one-third chance that we have an unsuccessful mission but somehow make it back home. And there’s a one-third chance we never come back.” And Valerie was delighted with those odds. She would’ve calculated it to be even riskier. She was the daughter of a California Highway Patrolman, so she understood what it meant to know that there’s a chance that someone very important to you might not come home that night.

So this is what these women were made of. They’re incredible women, and I spent a lot of time with each of them. Well, with Marilyn and Valerie. Susan Borman, by the time I met her, was in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s and really couldn’t communicate. But I certainly understood what she meant to Frank. It seemed difficult for him to answer any questions without saying how much he loved his wife and what she meant to him. And I saw it in person over and over.

So this was, unbeknownst to me when I began working on this, a really love story and a story of relationships and families like I’ve never across before. It was a wonderful bonus to me, and I tried to make it a very important part of the book because it was a very important part of this mission.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You did a great job with that. Well, get me to the mission. I thought this was interesting, talking, you know, hinting to that point that these guys are just regular guys. You talk about what they did before they headed over to the Kennedy Space Center. I guess that’s in Florida, right? Or is that in Houston?

Robert Kurson: Yes.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Florida.

Robert Kurson: They’re going to launch from Florida, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, they launched from Florida. Frank, like he was just, he’s cleaning out the garage. He was washing the car. It was like any other Saturday, and then he’s like, “I’m going to go to the, I’m going to be at the moon here, in a week.” But it’s just like a normal day.

Robert Kurson: Yeah. If anything, he’s saying, you know, “Don’t open my presents. Wait for me to come back,” because they’re going at Christmas. And they are balancing checkbooks, they’re painting. I think Jim Lovell did some, a little bit of painting of the house. And they’re just … But you know, think about it. These guys have to be, by DNA, a little bit different from the rest of us, in order to think about climbing on a 360-foot tall rocket that has flown only twice and failed in its second flight, really, and go to the moon, where no one’s ever gone before.

And so in a certain way it makes sense that they’re so even-keeled about this so close to launch.

Brett McKay: Alright. So let’s talk about the mission itself. Successful launch, and everyone … I mean, again, this is the first time, so no one was sure how things were going to go. It could’ve just exploded off the launch pad. But there was this successful launch. Did everything pretty much go according to what they planned, getting to the moon and starting that orbit?

Robert Kurson: Well let’s talk about the launch for just one second. For the four months that the astronaut were training, they were almost non-stop in simulators. And these were the greatest simulators ever built, and they were supposed to be able to approximate almost anything that could have occurred on their launch. Within a second or two of the launch, Bill Anders believed that the rocket’s fins were being shorn off by the launch tower. It was so much more violent and so much more crazy and terribly shaking than anything the simulator could ever reproduce, that he believed something was going wrong.

It was so violent the astronauts could not see their instruments. They could not communicate with Mission Control. Only thing, they couldn’t control their limbs. The only thing Anders really could see was Borman take his hand off the abort handle. Borman told me he would rather have died than abort by mistake, and he means that literally. And so for about 8 or 10 seconds, Anders thinks, “This is so much more terrible and violent than anything we experienced in simulation. Something has to be going wrong.” But 10 or 12 seconds after launch, that Saturn V has cleared the launch tower and they all realize, “We are actually on our way.”

And indeed they were. And the Saturn V delivers them first into Earth orbit, and it does it perfectly. They’re in Earth orbit for about, I don’t know, 90 minutes or two hours, to make sure everything’s okay and checking out. And then it comes time to do a maneuver called trans-lunar injection, TLI. And this is something that’s never been done in the history of the world. This is when they have to re-light the third stage engine and set course for the moon. And if the countdown happens to that … Chris Kraft, who’s in charge of Mission Control, is watching this and he sees the engine light and he sees the green blip on the screen in Mission Control go from an orbit around Earth outbound now.

And this is the first time human beings have ever left home and ever set out in search of another world. And Kraft, who’s made the rules for Mission Control, is overwhelmed, as are so many others in Mission Control. There are tears. And Kraft, one of Kraft’s rules is, “Nobody talks to the astronauts but another astronaut,” who’s called the CAPCOM. But Kraft is so overwhelmed by the moment he has to say something. He knows he can’t get on the radio to the astronauts, he made that rule. So he says out loud into Mission Control, to everyone and to no one all at once, he says, “You’re on your way. You’re really on your way now.” And in fact, that was true. For the first time in our existence, mankind had left home and set course for another world.

Brett McKay: Are these … I wanted to point out too, this point, the Russians hadn’t sent that mission. They had a chance, like early December, to do it, but nothing happened. And that’s when they realized, the Americans realized, “We can be the, we’re going to be the first ones there if this goes according to plan.”

Robert Kurson: I’m so glad you reminded me of … The Soviet launch window was December 6th, 15 days before the launch of Apollo 8. And people, and Mission Control were watching by the minute to see what was going to happen. They were certain it was going to happen because the Soviets had, what at least appeared to be, two perfectly successful launches, unmanned, around the moon before that. But nothing happened on December 6th or December 7th, and pretty soon it became clear to the Americans that they had the chance, with Apollo 8, to send the the first human beings to the moon.

It turns out, the Soviets likely had a crew at the launch paid in Kazakhstan and a fueled rocket there. But because there were problems on their two previous launches that they never let the world know about, it was, a decision was made not to send them. It was viewed as too risky. But they didn’t worry too much about it because even in December, just a couple weeks before Apollo 8 was scheduled to launch, many people in the Soviet space program did not believe the Americans, no matter what they were saying about Apollo 8, would be crazy enough to actually do it.

It was so dangerous and so risky to send people with four months of training so suddenly, many of the Soviets didn’t believe Apollo 8 could possible happen. And even when it was in flight, in its first hour, some people in the Soviet Union still didn’t believe it. That’s how crazy they viewed it.

Brett McKay: And so they passed that point where the Earth’s gravity no longer has an effect on the module and the moon’s gravity now is a big deal. What happens as they get closer and closer to the moon? Any other problems? Or are things just going according to plan? All the calculation they put in the software, just working great?

Robert Kurson: Everything’s working great. Frank Borman, however, gets very sick on the way to the moon and it’s a total mystery. He thinks it’s because he took a sleeping pill, and he’d never taken any kind of medications before. But for whatever reason, he’s very sick and there’s vomit and there’s diarrhea in the cabin. Bill Anders described it, I know this sounds crazy, but he described it with such poetry and beauty to me about how things looked and that, even though it was terrible to see these things floating in the cabin, they were wondrous examples of Newton’s laws of physics and … But it was a very big problem. We probably don’t have time to go into it, but it very nearly turned this flight around.

No one understood why Borman was sick. And he’d never, since he started taking flight lessons when he was 15 years old, had ever been sick in an airplane or a fighter jet or a test aircraft or even a spacecraft. And here he was, deathly sick. And NASA had to figure out what to do, because if he had something contagious … I mean, 30,000 people were going to die that year from the Hong Kong flu. If he had the Hong Kong flu or any other contagious disease or sickness, his crew-mates were going to get it soon enough. And it would be hard enough with one sick person, but three? They came very close to turning this around, but finally decided to let it continue.

Other than that, the flight is going beautifully. Except that even as the flight approaches the moon, Lovell makes a very strange broadcast to Mission Control. And he says, you know, “As a matter of interest, we have yet to see the moon.” The way they are positioned in the aircraft, they’re looking back at Earth. And by the way, of the many, many firsts that occur on Apollo 8, here’s another one. These are the first three human beings ever to see the Earth as a complete sphere. And by the time they’re closing in on the moon, the entire Earth fits behind Lovell’s thumbnail. But they still haven’t seen the moon. But that would change very soon.

Brett McKay: And that’s when they got into orbit, that’s when they went behind the moon. They were the first humans to go behind the moon and see what we call the dark side of the moon.

Robert Kurson: Right. Remember that we always see the same side of the moon from Earth. No humans had ever seen the far side of the moon before Apollo 8 approached. And Bill Anders was looking out the window and he sees millions of stars. It seems like millions of them. And he’s, but he’s not seeing the moon yet. And all of a sudden, out his small window, it goes black, and he thinks, “Oh, right when we’re getting close, there’s an oil spill or oil drippage across my window and I can’t see.” And then he told me that’s when the hairs on the back of his neck stood up, because he realized that was not oil. Those were the mountains on the far side of the moon.

These three men had now become the first human beings ever to arrive at the moon, and the first human eyes ever to see the far side of the moon. They had arrived.

Brett McKay: I mean what, I mean, and you know, Lovell was a romantic. Was Borman, did he, would that experience like elicit any type of emotional response in him, or was he still kind of all business? Like, “Alright, we got to get back to checking calculations”?

Robert Kurson: No, he was every bit as human as the others. Because he had told them, in their training and their flight planning, “When we get there, I don’t want anybody looking out the window. We have to stick straight to the flight plan. We have to do everything by the book.” But Lovell told me, when they got there, the three of them had their faces pressed up against the window like three kids looking into a candy store. They were overwhelmed. It was beyond anything they could have imagined. Here they were at the moon, and they had made it.

Brett McKay: So not only were they just going to go behind the moon, they were going to actually get in orbit. And so they were going around the moon. How many times did they go around, orbit the moon, on that mission?

Robert Kurson: The flight plan calls for ten orbits over 20 hours, so about two hours each orbit.

Brett McKay: Okay. And on, I guess on one of their final orbits, it’s on Christmas Eve and there was going to be a special broadcast to the entire world. And this is something people don’t realize, that NASA just said, “You guys can say whatever you want.” Now I can imagine the pressure of, you have this televised audience, the whole world is watching, you’re up in the moon, there’s this momentous occasion, humans have reached the moon. What do you say? What did these guys end up saying at this special … ? I mean it was Christmas Eve, correct? Am I getting that right?

Robert Kurson: It’s Christmas Eve, they’re on their ninth revolution of ten, and all they’ve been told by NASA was, “Say something appropriate. There will be more people listening to you than have ever listened a single voice, ever.” Nearly a third of the world’s population, it was estimated, would be tuned in. And all the direction they were given is, “Say something appropriate.” And now Borman, who has the greatest laugh you’ve ever heard, he has such a wonderful laugh, he laughs every time he tells me the story. He said, “Can you imagine today, leaving that kind of thing up to the three astronauts? Now there would be 14 committees and 16 focus groups and ad agencies.” But they did leave it to the astronauts.

The astronauts couldn’t figure out something appropriate for the moment. But, so Borman turned it over to a literary and sensitive friend he had and asked for advice as the flight was closing in. That friend couldn’t help, so he gave it to another friend, and that friend was stymied. But at 2:30 in the morning, in that second friend’s bedroom, that man’s wife walked in and saw all kinds of crumpled up paper on the ground and said, “What’s going on here?” And the guy confided in here, “This is what the astronauts need.” It was top secret. And she said, “I know exactly what they should say.” She told her husband, he thought that was perfect. He reported it to Borman, who thought it was perfect. They wrote it down, the astronauts wrote it down on the fire-proof paper, put it in their flight plan, never told anyone.

Didn’t tell their wives, didn’t tell NASA, didn’t tell George Low or Chris Kraft, they just went. And so here they are, on Christmas Eve, on the ninth orbit, and they’ve already done something amazing. They’ve taken a picture on their fourth orbit of the earth rising over the lunar horizon. This is a photograph called “Earthrise”, which I argue is the, maybe the single most powerful and important photograph ever taken. We’re looking back on ourselves. So they’ve done something incredible.

But here, the whole world is tuning in. It’s not just the three of them. And so they’re giving a tour of the moon, it’s being broadcast live to much of the world. And right at the end, when they have a couple minutes left, Borman announces that they have a message for the people of the world. And he turns it over to Anders, and Anders begins to read the first lines from the Book of Genesis, “In the beginning … ” And people in Mission Control immediately break into tears. This is a message for everyone. This is a message to the entire world, at the end of one of the worst, most divisive, violent, and destructive years in American history, a year that saw the assassination of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, in which there was violence in the streets all over, including in my hometown of Chicago, in which 15 dead, 15,000 Americans would die in Vietnam, and so much else had gone wrong.

Here the men are speaking an origin story, a story for everyone. One that so many of us can relate to about how we got here and how we are all of one. And it’s exactly about what they’d seen shooting that “Earthrise” picture. There are no continents, or countries, I should say, there’s just a single blue marble hanging in an infinity of space. And they were reading from the Book of Genesis. And Anders reads his lines and Lovell reads his lines and Borman finishes with his lines. And by the time Borman’s done, people around the world are in tears. And Borman says he wanted to wish everybody on Earth a Merry Christmas. “Merry Christmas to the people on the good Earth.”

And the broadcast goes dark. That moment, they lose their transmission. And around the world, there are reports around the world of people streaming out of their homes, out of buildings, out of taverns, out of apartments, looking skyward to try to catch a glimpse of these three men in their tiny spacecraft who had spoken to so many of them, spoken so inspirationally, knowing it’s impossible to catch a glimpse of them, but looking for them nonetheless. It was an incredibly emotional, important moment, at the end of this most terrible of years.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that moment, I’m … I got teary-eyed when you were describing it. I mean it’s just super powerful. So they finished the orbit, they head back home. And this was fraught with potentials of disaster and things could go … Like they weren’t out of the woods yet, things could go wrong here. But did everything pretty much go according to plan when they were getting back to Earth?

Robert Kurson: Well, there was … It didn’t look like right away. They needed to get out of lunar orbit. And in order to do that, they have to light that single engine, that engine that has no backup, because they have not taken a lunar module. And it has to be done precisely. And NASA knows that they’re going to get a call from the astronauts if everything went well at this precise moment. And that call does not come in. And it doesn’t come in five seconds later. It doesn’t come in ten seconds or even a minute later. Several minutes pass, and they don’t hear anything.

They think there’s every chance that this crew might have been lost. But that ends up being an antenna problem. So they did actually light that engine and get out of lunar orbit. Now they need to cruise home. And on the way, there is a very dangerous episode in which a mistake by Jim Lovell instructs the spacecraft itself that it’s been on the launch pad in Florida. And that disorients the entire spacecraft, and it’s such a dramatic development. And the astronauts and NASA have to work so brilliantly to correct the mistake. But Lovell told me later that he learned so much from that mistake and from correcting the mistake that would help him later on Apollo 13, when the spacecraft was in real trouble itself.

So this is a really dramatic return home. And then the re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere had never been done, and lunar distance, that kind of speed, and that’s just an unbelievable event as well. And then they’re home.

Brett McKay: And then they’re home. And you know, jubilation. And that kind of, that, they were the first to make it to the moon. That led on to Apollo 11 landing on the moon. I’m curious, like what happened to the Russian, the Soviet space program after the U.S. beat them to the moon? Did it kind of just … Did they just stop?

Robert Kurson: Yeah, well they never did make it to moon. And I think what they did is refocus their energies on space stations. Somewhere, something that was realistic, more realistic, in which they could take the lead. I think this flight was devastating to them. If you talk to cosmonauts or read interviews with cosmonauts, you’ll see that this was a devastating … When they realized that this actually was occurring, and this was not a propaganda broadcast, this was real, it was devastating to them. They truly believed they could’ve done it first and should’ve done it first.

But they gave all due credit. You have to say they really respected the astronauts and NASA and what they’d done, and really gave them their due. And they viewed it as the United States had just won the Space Race. When the astronauts return, there are ticker-tape parades for them everywhere. This is a victory unlike any other. And there are millions of people show up in major cities across the country, in New York, Chicago, in Houston. The astronauts were celebrated. Tens of thousands of cards and letters and telegrams pour in.

And of course the astronauts can only read a small fraction of them. But Frank Borman got one that he told me he remembered, knew he would remember forever. It had come from an anonymous person in the Midwest and it was only four words long. And it said, “Thanks, you’ve saved 1968.” And that’s how so many people felt. When Apollo 8 launched on December 21st, 1968, TIME magazine had already decided on The Dissenter as its Man of the Year. And of course that made sense in this most terrible of all years.

By the time these first three humans who had ever left home and visit another world and returned, by the time they came back, TIME magazine had changed it’s Man of the Year to the crew of Apollo 8. That’s an honor they wouldn’t even bestow on the crew of Apollo 11, the first landing mission, which gives you an idea of what this mission, Apollo 8, meant to the United States and to the world at the time.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, Robert, as you were, you had to talk to these men, the crew, the people involved with this mission … I mean, I imagine you couldn’t walk away interacting with these people without taking away some life lessons. I mean what, how are you changed in learning about this mission and writing about it?

Robert Kurson: Well, one of the things that changed me profoundly was the belief now that even things that appear absolutely impossible are possible if you believe in them enough and it means enough to you. This flight really should have been impossible under the circumstances. But because we viewed the mission as so important and because we viewed it in an existential way, that we really, it was part of our survival in many ways. And because nobody had the sensibility enough to understand that this was impossible, we went ahead with it anyway. And it happened. And that’s incred-, remained incredibly inspiring to me. It made me very proud of our country and very proud of what it meant to just think, “We are going to do it, even if it is impossible.”

That just is going to stay with me forever. The other thing that really affected me was the astronauts’ relationships with their wives and their families. Apollo 8 was the only crew, for any of the Gemini flights or the Apollo flights, which were the multi-manned crews, in which all the marriages survived. And marriage was a very difficult thing for astronauts. They were away from home all the time. Bill Anders told me once he’d calculated, around the time of Apollo 8, that he was able to spend an average of 11 minutes each, with each of his five kids each week. That’s all he could.

And the astronauts are away from home, they’re magnitudes more celebrated than rock stars, even. They are beyond rock stars. They’re wanted by everybody, there’s a lot of temptations, they’re on the road all the time. But these three men married childhood sweethearts, and these women were incredibly important to them. And that was really inspiring to me as well.

And the other thing is just, as I mentioned before, just how regular, nice guys these were. You’d figure guys who were so brilliant academically and such accomplished fighter pilots and test pilots and devoted their lives to the military, were somehow a different species. But in fact, they were so much like ordinary, nice guys, regular guys, that that seems to have stayed with me all this time as well.

Brett McKay: Well, Robert, this has been a great conversation. And I encourage everyone who’s listening to go get the book because it’s a fantastic read. Even though you know how the story ends, you’re going, like you’re not going to want to put this down. Where can people go to learn more about the book?

Robert Kurson: Oh, you can go to my website. It’s just my name, Robert Kurson, K-U-R-S-O-N, robertkurson.com.

Brett McKay: Robert Kurson, thank you so much for your time. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Robert Kurson: A total pleasure for me, Brett. Thank you so much for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest’s name is Robert Kurson. He’s the author of the book “Rocket Men”. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at robertkurson.com, that’s K-U-R-S-O-N. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/rocketmen where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. And if you enjoyed the podcast, you got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. As always, thank you for your continue support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.