Johnny Cash, “The Man in Black,” said he wore all black on behalf of the poor and hungry, the old who were neglected, “the “prisoner who has long paid for his crime,” and those betrayed by drugs. As a man who had grown up dirt poor, struggled his whole life with addiction, was thrown in jail seven times, and found himself in the proverbial wilderness during a long stretch of his career, Cash had a real heart for these kinds of folks; he was a man who had lived numerous ups and downs himself.

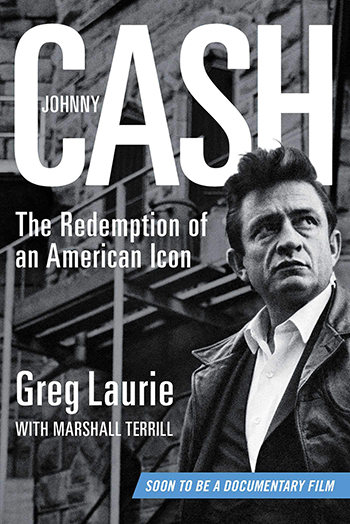

Marshall Terrill, co-author of Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon, will take us through these biographical peaks and valleys today. We talk about Cash’s hardscrabble upbringing on a cotton farm, his unfulfilled desire to please his father, and how his rise into stardom was accompanied by the arrival of a set of personal demons. We also discuss how, after becoming the top entertainer in the world, Cash’s career slid into two decades of music industry irrelevance, the big comeback he made near the end of his life, and the faith that sustained him through all his struggles and triumphs.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Marshall’s previous appearance on the show: Episode #673 — The Complex Coolness of Steve McQueen

- Cash songs mentioned in the show:

- Man in White — novel Cash wrote about the Apostle Paul

- Walk the Line movie

Connect With Marshall Terrill

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast, Johnny Cash, The man in black, said he wore all black on behalf of the poor and hungry, the old who are neglected, the prisoner who has long paid for his crime and those betrayed by drugs. As a man who had grown up dirt poor, struggled his whole life with addiction, was thrown in jail seven times and found himself in the proverbial wilderness during a long stretch of his career. Johnny had a real heart for those kinds of folks. He was a man who had lived numerous ups and downs himself, Marshall Terrill, co-author of the book Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon, will take us through these biographical peaks and valleys today. We’ll talk about Cash’s hardscrabble upbringing on a cotton farm, his unfulfilled desire to please his father and how his rise into stardom was accompanied by the arrival of his set of personal demons. We’ll also discussed how after becoming the top entertainer in the world, Cash’s career slimming to two decades of music industry irrelevance, the big comeback he made near the end of his life and the faith that sustained him through all his struggles and triumphs. After show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/cash.

Marshall Terrill, welcome back to the show.

Marshall Terrill: Hey, thank you for having me. Great to be back.

Brett McKay: So we had you on the show a while back ago to talk about an American icon of cool, Steve McQueen, The King of Cool, And you’ve co-authored another book about another icon of cool, that’s Johnny Cash, and Johnny Cash had interesting characters. He died back in, I guess, 2003 but he’s still relevant. He still, he’s like Steve McQueen. He’s just like… Man, he’s cool. I’ve seen 15-year-old kids who weren’t even born when Johnny Cash was alive and they’re wearing Johnny Cash t-shirts. Have you figured out what has made Cash such an intriguing character? What made him cool? Like Steve McQueen.

Marshall Terrill: It’s an interesting question because I think there’s an element of mystery there, we’re talking about icons from the 60s and the 70s where they weren’t in your face every day, so I think that that certainly plays a part in it. The other factor is that they were both rebels. McQueen, certainly more overtly so, but Cash was kind of like a country outlaw in that Nashville had its own establishment and rules, and Cash always played outside of those rules, and when he first came on the scene, was he rock and roll, was he rockabilly, was he country, nobody could really quite put their finger on the guy, and so I think that that element of mystery is kind of… It kinda chased him throughout his career.

Brett McKay: So as I read your book, Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon, three things stood out to me that I think contributed to that mystery of Johnny Cash. One, he had a life-long addiction battle, and we’ll talk about that. And then he also, in his career, it seems like he was always struggling to stay relevant and he wanted to be wanted by his fans, and then the other part of this underlying all of it was his deep abiding faith, and we’ll talk about that too, ’cause I think that also contributed to his coolness factor, ’cause the way he approached faith, it was different than a lot of other people. And as I read the book, it seemed like the origins of a lot of these things… It started in Cash’s childhood. What was his childhood like? And particularly, what was his relationship with his parents like?

Marshall Terrill: Well, his childhood, when you talk about the term dirt poor, that applies to him and his family because they were sharecroppers, and so they were always toiling in the dirt. And sharecroppers, the way that that whole system was set up was that they were never, ever gonna get ahead in life. They were always gonna be picking cotton, working the fields, and so, like I said, dirt poor is the terminology, but his childhood, it was sharecropping, it was church. There was a certain rigidity to his life growing up, there was no room for dreaming. There was no room for getting ahead in life. So it was always kinda…

So everything was kind of circled and centered around the church because that was really kind of the only relief that they could get, that was the only way that they could think of maybe perhaps a better life. And so it was a hard, tough life, especially for a dreamer like Johnny Cash, and so he also had a father, Ray, who was just a very stern, prototypical Depression Era father who… They had kids, and they had a lot of kids, and that was to help work the farm because those workers were… Is what kept them alive. They had to work hard every day of their lives, and that’s just what his life was like growing up, and then of course, you add alcohol to the mix, and his father was a big time drinker. It adds that extra element of misery to it.

Brett McKay: And the other thing you talk about in the book is that it always seemed like Johnny Cash could never get his dad’s approval no matter what he did, even as a boy, even when he was at the peak of his career, his dad was never impressed. Never. You’re still nothing.

Marshall Terrill: That’s correct. And you look, there’s a straight through line in that with a lot of famous people. The first person that comes to mind is Michael Jackson. I did a book on Pete Maravich, the great basketball player, he was always trying to not impress his father, but seek his approval. I remember just recently seeing the Elton John movie, and I didn’t know that he was trying to seek his father’s approval, and so I think with a lot of the greats, that’s the driving force, and I think if you look into… With Steve McQueen, he never knew his father, but he always wanted to find him and basically throw it in his face and say, “Look, I became a man. I became somebody much better than you could have ever anticipated.” So I think that those are… That’s that see-through line with all the great artists.

Brett McKay: Well, another thing that happened in his childhood that affected him profoundly is, he lost a brother, his brother died in a really tragic accident.

Marshall Terrill: Right, and that was not only impactful in his life, but that devastated the family. His brother Jack was two years older than Johnny, and Jack was… I guess it would be tough to call him a saint, but the kid never sinned, and he had this biblical knowledge and this knowledge about life way beyond his years. And so everybody had pegged Jack as he was going to be the preacher of the family, and in the deep south, that was like saying that you’re gonna become a lawyer. And so Jack was one of those kids that didn’t have to be told to do his chores. He wasn’t a dreamer.

Anything he did was to contribute to the family. For example, one of the reasons why he was killed was because he had an opportunity to go fishing with Johnny, it was like on a Saturday, or he could go to the high school and go to the shop class and cut up some metal piping, but he’d be making extra money, they’d make like an extra $2 and he’d give that to the family, and so that’s what he opted to do that day. And then, of course, he got into the terrible accident where the saw basically penetrated his whole chest, and then his innards kinda came out. And then he was in the hospital for a week, and then eventually he passed away. And so, not only was it the devastation of that accident, but it was what Johnny’s Dad said to him afterwards, and that was, “I wish it were you instead of Jack.” And so that haunted Johnny for years.

Brett McKay: Man, I mean, you can vicariously experience how awful that made him feel. It’s just such a gut punch to hear that from your own father. But the thing is, Johnny, he kept trying to get his dad’s approval. He never stopped trying to win his approval. There was another story you recount, it was later on his life when he was famous. He invites his parents over, and he invites Billy Graham over and his wife for dinner. Billy Graham, he was a big deal, it’s when he was at the height of his career. And after dinner, Johnny goes over his dad and says, “Dad, what do you think about that? Billy Graham, it’s pretty awesome, huh?” And his dad just tells him, “You still ain’t nothing boy.” I mean, he still… His dad never thought much of him, he still couldn’t please him. But what about his mom, what was Johnny Cash’s relationship like with his mother?

Marshall Terrill: His relationship with his mother was wonderful. Her name was Carrie. She was a very sweet and loving woman, complete opposite of his father. And I don’t mean to paint the father as this black villain, you know. The guy that wears the black cowboy hat, ’cause he was a guy that didn’t have a whole lot of education and had a big family and had to take care of them and… He was just a man of his time. The mother was a deeply religious, very sweet, and she always told John, JR is what he was called as a kid, that he had this gift. And so, she was the encouraging one. She was the yin to the father’s yang, and always told him, God has a purpose for you, and God has a purpose for your life. And so John, JR, took that to heart. Those were the two extremes that he had growing up, and of course, that began to manifest itself into adulthood.

Brett McKay: When did he start taking up singing?

Marshall Terrill: He started writing a little bit, dabbling. After Jack’s accident, the writing started coming through about a year or two after that, and then started singing maybe a couple of years after his accident. And then of course, when he was in high school, that’s when he was really… He was just kind of known as “the singer”. He was the entertainer in high school. And so that was kind of what his personality was like, but he had no ambition for it in anything beyond that. He talked about his greatest ambition one day was that he would be heard one day on the radio. It wasn’t anything beyond that.

Brett McKay: And then when did he decide to make a go out of being a musician? Like, he played in some shows in high school, but when did he was like, I’m gonna try to make this a profession. When did that happen?

Marshall Terrill: Well, I think that was after he was married, when he came back from his military service. And he worked for this guy, he sold appliances door to door. Can you imagine doing that these days?

Brett McKay: Jeez, yeah.

Marshall Terrill: And he just hated that. And the guy that he worked for, knew John was a good guy, and just kept fronting him this money, advancing him money, even though he was a terrible salesman. And then of course, when John made it big, he paid that guy back everything that he owed him which floored the guy. But to answer your question, when he came back from the army and started selling appliances, but he was also writing songs and singing songs. And of course, he lived in Memphis, which was home to Sun Records. And that’s when he started pitching Sam Phillips. And so again, it’s not a great ambition, more than a burning desire to get out of this life of selling appliances door to door. And then of course, when he learned that he could do that full-time, well then, he was full on for it.

Brett McKay: And what was the state of music at the time? This is like early 50s, this is kind of before rock and roll was a thing. This is before Elvis. This is before Jerry Lee. In fact, all these guys were at Sun Records. How would you describe… What was in the air? What was percolating? Like, how did that contribute to Johnny Cash kind of emerging as a big star during this time?

Marshall Terrill: Well, if you’ve heard of the term, “This was rock’s big bang”. This is when everything was starting to formulate, looking over the heavens and the Earth. In the rock and roll universe, it was rock’s big bang. All these guys were coming on the scene at the same time, in the same place, in the same city. You had Johnny Cash, you had Elvis Presley, you had Jerry Lee Lewis, you had Carl Perkins, and to some degree, later on, Roy Orbison, and all these guys were coming to this place called Sun Records. And so it was a mix of rock, country, and it’s what they called rockabilly. And so this was all 1954.

’55, ’56, when all this was happening. You look back later on and you go, “Wow, this is just… How does something like this happen?” In the ’90s, you had Seattle happening, in the ’60s, you had Motown, but this was the first post-war, where things were happening at the same time in the same city, and so it happened to be Memphis, and it happened to be these four or five people. And so that’s how it all started. But, Cash is part of that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and how did Johnny Cash see himself? Because, Elvis and Jerry Lee, those guys went on to be like, “We’re rock and roll stars. That’s what we do.” Did Johnny Cash put himself in a genre?

Marshall Terrill: No, he didn’t, and he never wanted to be put into a genre. I don’t necessarily think he saw himself as country, but I don’t necessarily think that he saw himself as rock and roll either. I’ve read a lot of his early interviews at the time, and I don’t think he wanted to be defined. And I think his early music certainly is beyond categorization, other than maybe it was rockabilly.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What was his big hit? What was the thing that really caused him to break out?

Marshall Terrill: Well, he had a couple of the regional songs. But of course, “I Walk the Line”, was his big, big breakout hit. And that was in ’56 because Elvis happened. And so, when Elvis happened then that’s what really inspired Cash. And then, those two actually ended up on the same bill at a lot of shows. But, “I Walk the Line”, was the one that became the household hit. And it was a crossover hit, so Cash, that’s when he became really the household name. The ironic part was, “I Walk the Line”, was a song written for his first wife. And she was bringing up the fact that, now that you’re becoming popular, I see all these screaming girls at these shows, and so he wrote this song, I Walk the Line, I walk the line for you. And ironically, later on that wasn’t the case.

Brett McKay: Yeah, we’ll talk a bit about that, what happened. But after “I Walk the Line”, his career just shot off like a rocket, and he was touring all the time and recording, and it was really demanding, it was wearing him out and to keep up with the demands, he started using amphetamines. When did this start?

Marshall Terrill: Well, this started, I wanna say, late ’50s, early ’60s. And this happened because rock and roll back then, it was pretty primitive. Think about this, we didn’t really even have a highway system at that time. When these guys were doing their one-nighters, they were taking these roads that weren’t necessarily freeway, they were taking county, country highways to get to the gigs, and sometimes they were driving 600 miles a night. If you can imagine that without a freeway. And so, they needed a little help staying up because they were driving four and five to a car, they had the instruments in the trunk, and this was their life. They loved it, but even though they were young, they were on the road hours and hours at a time, because when they finish their half-hour gig, then they were on to the next one. So these pills were a way to help them stay up on the road. And then of course, it developed into a full-time habit.

Brett McKay: And how did the drug use change him? Did it change him in the beginning?

Marshall Terrill: Oh, it absolutely did. It puts you on edge. You stay up 24 hours a day, then you crash, and then it’s like any addiction. The addiction takes over, and you are no longer yourself, you’re a slave to the drug. And so, it changed his personality in that way for sure. He became a little bit more selfish. Didn’t eat, got skinnier. At one point in time, I think he got down to 160-’70 pounds, and this was a guy that was like, 6’2, a big sized guy, and it was also breaking down his health which of course almost took his life later on.

Brett McKay: Well, and it seemed early on, he did a pretty good job of hiding the addiction, but then he had these moments where it started affecting his family and actually his musical performance. Were there anything that stood out to you as like, Yeah, this is… When people finally realized, yeah, Johnny’s got a problem.

Marshall Terrill: Well, one stands out. I kinda remember the story about, it would have been Jack’s 21st birthday, and John had his brand new house, no furniture in there yet. And he got the whole family together and he set a place for Jack. I think the insinuating being that Jack was gonna come to dinner that night. And then of course, he was acting very strange and bizarre around his family. Usually when you’re on drugs, Mom and Dad’s the last person that you’re gonna… You wanna try to hide it from Mom and Dad. Those are the last people that you want to know, but it all came out that weekend, I think. And then of course, they not only said he had a problem, but they said, “Our son ain’t gonna be around much longer.”

Brett McKay: The other thing that was interesting about his addiction is that he would have these come to Jesus moments where he’d be like, “Okay, I got a problem, I’m gonna commit to doing better.” But then he would back slide. And this is… I mean, it happened, I guess, throughout all of his life, even after into the ’70s and ’80s, he still was addicted to pills.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, he was. And that was the most frustrating part of writing about his life. He knew better, had people around him, had everything going for him, and then he would get to the point where he got so bad and addicted again… And then of course, he’d fall back on his knees and pray, and after a while you go, “Man, this is getting old.” But you have to… You just have to say, “Well, this is a person with an addiction.” And you can’t put any sort of normalcy on a person with an addiction. They’re gonna do what they’re gonna do, and they’re slave to it, and given the recovery rates are what 96, 97% chance that they’re not gonna recover? It’s a miracle that he stayed alive as long as he did.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. So you mentioned he started his music career after his first marriage. What was his first marriage like and what was family life like for him early on?

Marshall Terrill: Well, his first wife, Vivian, was a real sweet heart, and that was kind of… He recognized later on in life that he pretty much gave her a raw deal in that they met… I think they met the week before he was gonna go away to Germany, and they were just young lovers in the 50s where they meet and they had this wonderful time, they’re roller skating, they’re having dinner, they’re doing all of these wonderful things. He goes away and they promised to write each other every day, and they do, and they write each other every day while he’s away, because I think she had a collection of close to 10,000 letters if I’m not mistaken. But then when he gets back and they get married, the reality is something completely different. And then of course, when he fell in love with June Carter, it completely changed that dynamic. And so… But the sad part was, is that, he had children with Vivian, so that’s what also fed into the addiction was that he had this wife and these young kids, and he was gonna end up leaving them because he was in love with June Carter.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so let’s talk about that. How did he meet June Carter? And what happened to Walk The Line?

Marshall Terrill: Well, she was on the road with him. She was one of the acts that got hired on the road, and that’s how they got involved. The movie is really not reality, the movie, “I Walk The Line” because I think the movie tries to portray that they didn’t get involved until after she was divorced and that wasn’t the case.

Brett McKay: But after they got married, it seems like that was it. It was a life-long relationship with them.

Marshall Terrill: Yes, it was. And there’s no mistaking that the two were in love, and I really think that June Carter was the love of his life. But it just so happened that unfortunately, he got married to Vivian, realized that she wasn’t the love of his life, and then of course, they had children, and then later on he had this whole other life with June Carter.

Brett McKay: And you said that at the end of his life, Johnny Cash kinda recognized that he gave Vivian the raw deal. At the time, how did he reconcile it? Did we have any ideas?

Marshall Terrill: Well, I know that they became friendly at the end of their lives because she actually came to pay him a visit to ask permission to write her book, and he said, “Hey, if anybody deserves to write a book, it’s you for putting up with me.” And so he was good in that way, ’cause he did recognize that. But during their lifetime, I should say, right up to that point where he did see her regarding the book, I’m not so sure that they had reconciled anything, it was just John left and now he’s gone, and she had a really hard time. As a matter of fact, she was losing a lot of weight and she finally had to see a doctor, and the doctor said, “You need to do something, ’cause what you’re doing, what you’re doing now is gonna put you in the grave,” he goes, “And you’ve got four young children and the woman that took away your husband is going to be raising your children if you don’t do something about it.” So that’s when Vivian said, Oh, okay, I need to now move on with my life and do something else. So she got remarried and had a very happy marriage to him, but Johnny was the one that just cast that long shadow over her life.

Brett McKay: Alright, so throughout the ’60s, this is like when Johnny Cash’s career started taking off. How popular was he during the 1960s?

Marshall Terrill: Oh, at one point, there was a golden period from 1968, where he did Folsom prison to then the following year, he had the TV show, and the TV show ran from ’69 to ’71. 1969 he outsold the Beatles, outsold the Rolling Stones. So can you imagine somebody today with a very popular TV show, who could actually go out and tour and then put out all these number one records? I can’t think of anybody today that could do that, but that was really his golden period in the late ’60s, believe it or not. So he had a fan base of people who already knew him, and then he also had a younger fan base, and these were the rock and roll kids, because when he had his television show, from ’69 to ’71, the show was based out of Nashville, but he was the first country guy to invite other rockers on his show, so he had Dylan on his show, Creedence Clearwater Revival, he had a lot of rock and roll acts.

So on his show you’d see rock, gospel, country, you’d even get some old jazz artist or some old R&B artists. So Johnny was just a big fan of music. And so he, again, it goes back to, he didn’t wanna be defined, but he also didn’t wanna define what acts would be on his show, he just wanted to introduce good rock music. So at that point in time, that’s when he created the Man in Black persona and the only people that the rockers really kind of respected in country was Johnny Cash. And he also had the respect of people from the previous decade, and he also had the respect of country. So at that one point in time, Johnny Cash was the number one entertainer in the world.

Brett McKay: But during this time, he’s still battling addiction, correct?

Marshall Terrill: Up to Folsom. Folsom was kind of his big come back and kinda like his big sobriety, and then so was the television show, and then he became… He rededicated himself to his faith because of all the good things that were happening to him, he didn’t really fall back into addiction again until like the late ’70s. So there was a period there of a decade where he didn’t have any issues with addiction.

Brett McKay: So he had this high point, ’68 through ’71, but then in the ’70s, his career started to take a slide. What do you think happened there?

Marshall Terrill: Well, I think that happens with every career; It’s what I call the mid-career slump. All of a sudden you’re no longer, I guess, relevant would be the term, but music is a young person’s game, and you can’t be a rock star forever. The stones and Paul McCartney, yes, they’re rock stars, but let’s be honest, the last time they had a hit were in the 80s, so that’s four decades ago. So what happens is, then you start… After a while, then you start living on your legend, and so Cash wasn’t quite there yet, so what he had become was a irrelevant artist by 1972-73, and then that lasted for two decades. He really couldn’t catch his momentum again until the 90s.

Brett McKay: No, it was so bad. You described… I felt really bad for him. He got dumped by, I think it was Columbia, and then he had to basically audition. He was just starting out to even get a record deal.

Marshall Terrill: Not only that, but he had these young punks who kept him waiting in the waiting room and/or would just blow him off all together. It was really painful to hear those things because he certainly didn’t deserve that. He had one guy that he went up through the ranks with, and he just said, Man, I can’t believe Johnny Cash is auditioning for me, and Cash did it and still the guy wouldn’t give him a record deal. With the money guys, it’s always, “Okay, I’ll give you a record deal, but it’s not gonna be the same money that you used to make unless you sell records.” So that’s kind of where Cash was in the 70s and the 80s.

Brett McKay: You had this great line, you described him as he was respected but not relevant, and that’s like the worst place for a musician to be, or an artist to be.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, and you can say that about a lot of artists today. A lot of legacy artists, you can say that about, relevance really is only with the younger audience, and they decide who is relevant and the reasons why they’re relevant is beyond me, but everybody gets there.

Brett McKay: And how did he handle this low period in his career?

Marshall Terrill: I don’t think he handled it very well, he had to go to Branson, which for a country artist, that was like the signaling of, “Okay, my career is over, and I’m gonna catch what little fame there is to catch by going to Branson.” And so he didn’t wanna do that, but that’s kinda just where he was at that time. Yeah, it got as low as you could get, there were sometimes when… Then the money stopped coming in, and he and June had to, at times pawn some jewelry to pay their staff, because what happens is that you developed this certain lifestyle, you’ve got a recording studio, you got homes, you got vacation homes, you’ve got staff. And I’ve written about Elvis Presley, I just finished a book on him right now, and so he fell into that same trap as well. Elvis you would think had a whole lot of money, but he didn’t have a whole lot of money at the end of his career, and so they developed this lifestyle, and so when the hit stopped coming and the money stops rolling in, what do you do?

Brett McKay: And you also talked about he even got desperate, this is one point where he wrote this kind of novelty song, it was like the chicken in black, and he dressed himself up like this kind of weird bank robber, and all of his friends were just like, “Johnny, what are you doing? This is so beneath you.” But I think he wanted… He was trying to stay relevant again, trying to get another hit.

Marshall Terrill: Well, and somebody, a historian named Mark Steeper, who was very helpful to me on the book, pointed out that Johnny had a history of doing some novelty hits, A boy named Sue was a novelty hit that turned out well.

Brett McKay: One piece at a time.

Marshall Terrill: One piece of the time, was another one, so Johnny felt like that it was probably time to do another one, and it just so happened that chicken and Black was just so bad that it pretty much ended up just trashing his career.

Brett McKay: Okay, so yeah, he goes to Branson, he wanted to create… Basically, he was trying to create another Dollywood, but it’d be like Johnny Cash land, and that ended up into sort of a dead end. Then in the early ’90s, starting in the early ’90s, there was this Johnny Cash revival. So what happened that allowed Johnny Cash to have one of the greatest… I would say it’s one of the greatest second acts in music history, what happened?

Marshall Terrill: Oh, I agree with you. I think it could be perhaps the greatest comeback, greatest second act of all time. Well, it started with U2, and in the 80s, I think U2, a couple of members of U2 were driving through the country and they were driving through Nashville and they wanted to meet Johnny Cash, ’cause they saw him as this legendary figure and Bono especially connected very well with Cash, and they just had a nice meal and Cash prayed, and Bono was really taken by that. And so he never forgot it. So a few years later, they were recording, they had recorded a song that they felt was right for Cash, and so I think it was on the Zooropa album, and so they not only did the song with him, they did this video, and the song and the video were amazing, can you imagine U2 backing you on a track, and the song came out great, and then it was placed on this album as a mystery track, and then they did a video for it, and then it showed Cash in his heyday.

And so that was the start of it. And then Rick Rubin then sees him playing live, and Rick Rubin was the hot producer of the day and decided that he wanted to produce Cash, and so he did, and that pairing was called The American recordings, and so they made three or four of those albums, and so Rick Rubin was kind of a very successful hip-hop producer and produced a lot of things that were relevant, so you’ve got U2 and then you’ve got Rick Rubin who present this guy again and say, Hey, this guy is really cool. This is the guy that started it all. And then that’s when all the young people then decided, okay, let’s explore who this guy is, so that’s where Cash had his big second come back.

Brett McKay: And in those Rick Rubin albums, a lot of them were… A lot of songs he recorded, they were cover songs of… From other artists like Tom Petty, Nine-Inch Nails, but what was interesting is that Cash was able to make it his own with his own unique take on it.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, and it was just Cash in a guitar sometimes, and it was this haunting voice and… Yeah, this was a Generation X that really connected with him, they just… They connected with a man in the black, the man in the black jacket, the man that had survived all this and is still singing, and so he was… Again, he was relevant again. And that’s really tough to do when you’re in your 60s.

Brett McKay: So this went throughout his 60s and he died when I guess he was 71, right?

Marshall Terrill: Right.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that last set. There’s some really good songs like that “Hurt” video. I always cry when I watch that “Hurt” video it is so… ’cause you know what like… You can tell he’s talking about his own addiction, and his own struggles, and you see the Johnny Cash land just sort of kind of empty and broken, and it’s really poignant. It really does… I get teared up every time I watch it.

Marshall Terrill: Oh, and it’s pure artistry because he put himself out there. Everybody always tries to put their best foot forward, but Cash was like, No, this is who I am, this is my life now, and yeah, there was something really, really strong about it and it connected with that MTV crowd.

Brett McKay: All throughout his ups and downs of his life, was his faith, but it was… How would you describe it? ’cause I think it’s hard to describe. He’s not like your stereotypical Ned Flanders churchy Christian guy. But he was deeply religious. How would you describe it?

Marshall Terrill: Well, he had this great wisdom about him, and he studied the Bible, and when I say studied, I’m not talking about a home study, I mean he was an ordained minister, and he actually got a degree, and I actually interviewed the gentleman who gave him the degree and he said the assignments that he turned in were the most profound and the deepest that he had ever seen in his career, and he had been doing it for 50, 60, 70 years. So that kind of just shows you where cash was. Cash also came from a long line of preachers, so this was in his blood and this what he wanted.

Again, for me, the frustrating part was, and I am not one to judge, but it was like, Okay, so you know these things, you have this great wisdom and yet you couldn’t stop yourself when the time came, so there was always this falling down, dusting himself off and getting back up again. And that happened throughout his whole life, so it’s just interesting, and wanting to get baptized again and going to Israel and walking the streets and not only knowing the knowledge, but knowing where these places were and seeing these places first hand and making a film about Jesus and putting all of his money up to make the film, so it was a real faith.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, he also wrote a book about Paul the Apostle. Right.

Marshall Terrill: That’s right. It was a fictional account, but… Yeah, so he was successful on many levels as an artist. He was a great songwriter, singer, could act in television and movies, and then he wrote a fictional book, I mean the guy was just incredible.

Brett McKay: And the way you describe it too, is that he was deeply religious and he wasn’t afraid to share it; His faith. But the way you describe, when you interview some of the people he ran with in his heyday, some of these guys, they didn’t believe in God, they weren’t religious, and they described like even when Cash got religious with us, it didn’t feel like put upon. It just felt like the most natural thing in the world.

Marshall Terrill: Right, exactly.

Brett McKay: And it didn’t… So as a consequence, it wasn’t off-putting. They’re just like, Okay, this is important to Johnny, and I’m gonna respect that.

Marshall Terrill: Well, and the best story of that comes from the actor, John Schneider, he did a TV movie with John, and he actually lived with Cash and his wife June for a couple of months, and they’d go fishing together. They do a lot of things together. Cash never talked about religion to him, but he had a bible in the trunk of his car. They’d go fishing and then john would say, “Well, time for me to go and study my Bible, and through that example, John Schneider, always said, “You know, if a man’s man like Johnny Cash has to go every day and study the Bible and crack it open, there’s gotta be something to it.” And so he influenced people in that way.

Brett McKay: What would you take away from Johnny Cash? Do you think there’s anything we can learn about living from his life?

Marshall Terrill: Well, again, he was a man of contradictions, and the people of contradictions are always the most interesting to write about. It’s also frustrating in a way, but that’s the thing about artists, is that artists are artists and you can’t… They don’t live neat clean lives. They live messy lives, but in the case of Cash, he always knew where to go back to, and that was… He drew upon on his faith that was kind of like his center and his home, so that’s what he would always go back to, and that’s where he was at the end of his life.

Brett McKay: And I think the take away for me is like, don’t ever give up. And that’s the thing I got from Johnny Cash, he was relentless, he just kept trying and trying, and I’m sure there’s people who are listening who have struggled with their addiction or know someone that has an addiction, you just wanna feel like you wanna give up, but I think there’s something from Johnny Cash you can learn. You just gotta keep trying man, you gotta get back on the saddle and get going again.

Marshall Terrill: Well, and that certainly speaks to not only his personal life but his professional life. He knew his fame had been slipping away, and he knew that his relevance was slipping away. For two whole decades he clawed and clawed and clawed, and finally he got back there again before he passed, and so that was kind of the beautiful thing to witness is that he wanted that one last turn in the sun and he got it.

Brett McKay: Well, Marshall, this has been a great conversation. Is there some place people can go to learn more about the book?

Marshall Terrill: I think the best way just to go to Amazon and buy a copy of Johnny Cash: The redemption of an American icon, and then a documentary is going to be based on this book, we don’t have a title for it yet, it wraps the end of this month, and they should probably be looking for it some time in the Fall of 2022.

Brett McKay: Fantastic, well Marshall Terrill thanks for your time, it has been a pleasure.

Marshall Terrill: Thank you so much.

Brett McKay: Well, my guest here was Marshall Terrill. He’s the co-author of the book, Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American icon. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about his book at our show notes at aom.is/cash where you can find links to resources and we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM podcast, make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives as well as thousand articles or interviews about pretty much anything you’d think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes of the AoM podcast you could do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code “manliness” to check out for a free month trial. Once you signed up, Download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad free episodes of the AoM podcast. And if you haven’t done so, already, I would appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review of Apple podcast or Stitcher, helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member, who you think will get something out of it, as always thank you for the continued support, till next time. It’s Brett McKay. Reminds you not only listen to AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.