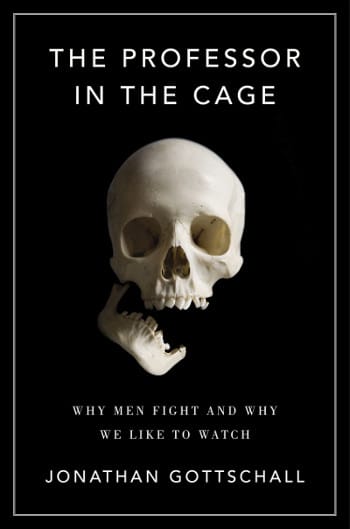

Jonathan Gottschall was an associate professor of English whose career had stalled in mid-life. Then one day he looked out his office window, saw a MMA gym across the street, and decided he was going to train to become a fighter. He wanted both to prove something to himself and to gain firsthand experiences to draw from in writing a book about the biology, anthropology, and sociology of male violence. The result was The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch. In this episode I talk to Gottschall about violence and masculinity and why getting in a fight may be the best thing a man can do for himself.

Show Highlights

- Why an English professor decided to become a MMA fighter in middle-age

- How Gottschall’s assumptions about violence changed after his training and research into male violence

- How MMA training benefited other areas of his life

- The role of honor in male violence

- How ritualized violence is a benefit to society

- Why some sociologists think we need to bring back the duel

- Why we like to watch other men fight and be violent

- Why men like to fight more than women

- And much more!

The Professor in the Cage hits on a lot of the themes we’ve written about on AoM. If you enjoyed our honor and manhood series, then you’ll certainly get a lot out of this book. It’s one of the best books I’ve read about masculinity and one of the best books I’ve read so far this year. I highly recommend that you pick it up and give it a read.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Special thanks to Keelan O’Hara for editing the podcast!

Transcript

Brett: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. So, why do men like to fight? Why do we like to compete? Whether it’s boxing or MMA, football, basketball, any of that type of … We’ll come up with a competition for anything. Not only that, why do we like to watch other men fight and to compete? What’s going on there?

Well, our guest today is an English professor that wanted to find the answers to those questions, so he decided to train to become an MMA fighter. His name is Jonathan Gottschall. He’s the author of the book, “The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch.” This is one of the best books I’ve read so far this year, and one of the best books about masculinity I’ve read.

He weaves in a story about his training to become an MMA fighter with anthropological, biological, sociological studies about male violence, male competition, and male status. And it just provides a lot of fascinating insights to how these aspects of masculinity have shaped men throughout time, throughout cultures, and he makes the provocative case that ritualized combat, whether it’s boxing or MMA, competition in violent sports like football, serve a role in society and actually a pro-social role so we’re going to talk about what role violence should have in a man’s life, even in the modern world.

Again, it’s fascinating, provocative argument and discussion. I think you’re really going to like this one, so let’s do this. Jonathan Gottschall, the professor in the cage. Jonathan Gottschall, welcome to the show.

Jon: Thank you for having me. I appreciate you having me on.

Brett: All right, so your book is, “The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch.” The first question is, naturally, you’re an English professor by trade, how did an English professor end up training to become an MMA fighter and explore violence and masculinity?

Jon: I guess two or four years ago I was an English professor but I was an adjunct English professor at a small liberal arts school, and I have never managed to find my way on to the tenure track and I was finally facing the fact that I was basically never going to. At that midlife, and I needed a new path through life, but I didn’t know what it should be.

Then one day I was at my office hours and I was pacing around and I look out the front window and this new business had moved in across the street and it’s called Mark Shrader’s Academy of Mixed Martial Arts. It’s a cage fighting gym. I could look across the street, you know, about as far as I could throw a snowball, and I could see the guys in there in the cage, and they’re dancing around, they’re hitting, they’re tackling, they’re rolling.

I was just ambushed by this powerful sense of envy. You know, I envied those young guys over there who seemed so alive in their cage while here I was across the street rotting away in my office cubicle.

I had this kind of funny thought and the thought was, “Wouldn’t it be funny if I went across the street and joined them?” Me, this chubby, 40-year old, never been in a fight, English professor. Then my next thought was, of course, “Well, maybe that’s my new path in life. Maybe there’s a book in that, a non-fiction ‘Fight Club,’ a book about the allure of violence.”

A couple of months later I worked up my courage, I crossed the street, tried to learn how to fight, and wrote the book.

Brett: What did your fellow colleagues think of this?

Jon: You know what? It’s funny. When I said that, I had this fantasy of crossing the street to learn how to fight. Initially, this fantasy was a career suicide fantasy. I was hoping that my colleagues would see me fighting in the cage and they would say, “Oh, this is beyond the pale of academic respectability. We must fire this guy.” It was like this career-suicide fantasy I was having.

My colleagues, unfortunately, were a lot more tolerant than I hoped. They didn’t fire me. They thought it was funny. They were pretty supportive in the end. I’m interested to see what the rest of the intellectual academic world is going to make of the book once they get ahold of it. Whether they’ll see it as this, I don’t know, glorification of barbarism or associated as a more thoughtful project than I intended.

Brett: Have you got any feedback from other academics?

Jon: Not yet. The book has only been out a few days. I’ve had a few reviews but not from the most pointy-headed intellectuals.

Brett: Sure. I’m sure that will come soon. What did your wife think of this? You’re a dad. You got two daughters. You’re 40 years old. Was she worried about this?

Jon: Yeah. At first, I didn’t want to tell her. I was embarrassed to even confess this to her but eventually I had to. I told her my whole dumb plan for trying to become a cage fighter.

First, she wanted to see if I was joking or not and then she said, “You know, you don’t have any skills. You’ll be killed,” she said. It always hurts to have your wife question your skill but eventually she came around to it. She got so comfortable with it, in fact that it depressed me. I’ll be like, “My shoulder hurts. I can’t see straight. I got hit so hard today.” I’d want to whine about it or something and she’d be like, “Did you unload the dishwasher?” I’d think, “My God, woman! Don’t you love me at all? Aren’t you worried about me at all?” She got used to it. She’s very supportive.

Brett: That’s great. Did you have any assumptions about male violence going into this experiment?

Jon: Absolutely. I was going in partially to verify a theory that I have. The theory was basically that MMA was this metaphor for something really dark and rotten in human nature, something black and violent, you know?

I had all the stereotypes that most people have. That the fighting was bad and that the fighters must be bullies or sociopaths or sadist at the least. I just didn’t find that at all. Almost all my assumptions going in were overturned by the process of doing the research, meeting the guys, fighting myself.

Basically, guys don’t go into Mixed Martial Arts because they’re dreaming of hurting people. They don’t do it because they fantasize about or take some kind of pleasure in doing violence. Most guys get into it, I believe, because they’re attempting to defeat a weakness and timidity inside themselves. These are guys who are in need of a quest and Mixed Martial Arts gives them that quest.

Brett: Yeah. There aren’t really opportunities for quest for men. In the traditional, we think masculine quest, right?

Jon: That’s right. You have a world where the world is getting safer and safer. It’s getting softer and softer. The traditional masculine virtues are held in lower and lower regard. There’s very few places where a young guy, this overwhelmingly young guy to do this, can go to get a right of passage into manhood. I think that’s what a lot of these guys are seeking.

They’re seeking some sort of test of their courage and their character. They want to know if they’re real men in that traditional sense.

Brett: Your point about MMA fighters not being bullies, my experience with MMA fighters, they’re some of the nicest people I’ve ever encountered.

Jon: Totally.

Brett: Super friendly and just … It’s not what you think. You think they’re these jerks. They’re just the nicest guys in the world.

Jon: I totally agree with you. I don’t know if it attracts nice guys. I think probably it’s the culture of MMA. It’s a martial arts culture which is based on respect but it’s also something like inside the gym, it really pays to be nice because if you’re not, then these people beat you up worse. They don’t want to work with you. You need to play nice inside the gym.

Also I think outside the gym, I think these guys are at pains to put people at ease. They want to make a very strong display of the fact that even though I’m a mean person in that cage, I’m a very nice person outside the cage and you don’t need to be uncomfortable and you don’t need to be worried.

Brett: Let’s talk about some of the … Even your story about training with all these fantastic research about masculinity and particularly how it relates to violence. I love you start off the book talking about honor. This underlies what brutal violence plays in masculinity. What role does honor play in male violence?

I guess the first thing it will be how do you define honor because I think most people have a definition of honor that’s not what you’re talking about.

Jon: I think it’s always been a fuzzy concept. It’s always been hard for people to put their finger on what they mean but if you substitute the word respect, you won’t be far wrong.

A man of honor is a man who demands to be respected. The most classic honor dispute is the formal aristocratic European duel where a man feels dishonored because to his opponent you must apologize for that for this. If you don’t do it, we’re going to have a gunfight or a sword fight at dawn.

Now, the classic European duel is death. No one does that anymore. But, we still duel. We still have the duel in the sense of an escalating dispute over honor. It’s still the leading cause of conflict and violence and even homicide among men.

For example, you’re at the bar. Some guy walks past you. You click shoulders. Somebody spills a drink. Someone insults someone. Before you know it, it’s escalated to beer bottles to the top of the head. That is, in a way, a duel. In that limited sense I’m talking about. It’s a dispute over honor that gets out of control.

Brett: Got you. I love how you talk too … We’ve had a professor who specializes in the civil war honor. She talked about the difference between aristocratic duels and the lower class duels, the rough and tumbles.

Jon: That was amazing, isn’t it?

Brett: You talked about that in your book, right? It was just no holds barred. Basically, the whole point is to gouge someone’s eye out.

Jon: That was the touchdown pass. It was called feeling for a feller’s eyestrings. The idea was to get your thumbs in to the corners of the eye and pop out the whole eyeball dancing around on the string.

Brett: When I read that, it just made me wince in pain. That is an example of the duel but for lower class…

Jon: Yeah. The duel is dead, people say, but the duel is only dead in that stuffy elaborate aristocratic form. There’s various other kinds and other forms of a duel that still exist today.

Brett: You talked about how duels in the other forms that exist today are basically ritualized violence. These forms of ritualized violence actually have a benefit to society. Can you talk exactly what you mean by ritualized violence and how does this actually keep violence in check?

Jon: Sure. Again, the history of the duel, if you have this story of talking about the duel, they usually go back 500 years or so in Europe but they really need to go back millions of years. If you’ve seen a couple of elephant seals clashing in the surf on a nature video or a couple of lambs squaring off and cracking skulls on the hillside in a nature video.

That’s what biologists call Ritual Combat. It’s this way that many, many different species have evolved to decide who’s the bigger, stronger, fitter animal without the dangers of fighting it out to the death.

What I argue in the book is that the same is true of people, only more so. Yeah, humans are complicated, complex animal but we’re animals still. The term I have for this is called the Monkey Dance. The Monkey Dance is my term for human versions of ritual combat. Everything from formal duels, deadly duels, to verbal duels, to play fights of boys, to sports.

Probably the best example of this is, again, going back to that bar. If you have the choreography of a standard fist fight … A fist fight almost always goes the same way. It’s the study by sociologists pretty extensively. They always had the same patterns. It begins as some sort of insult, some sort of trespass. A man will feel dishonored, disrespected. There’s a challenge. They close the distance. There’s a push.

At any time, either man can call it off and walk away, say I’m sorry but if you won’t, it will escalate to a real fight. There’ll be a push. There’ll be a punch. There’ll be a tackle. They’ll roll on the ground and gouge each other.

The choreography of a standard fist fight, the back and forth dance of it, the moves that the people carry out seem to be about as hot-wired into us as those two lambs cracking skulls on a mountain side.

The key is that all these stuff look silly. It looks ridiculous. It looks pathetic. Sometimes it ends in tragedy. But, for the most part, our monkey dances are a good thing. They keep our contest civilized. Without codes and rules and rituals to govern the way that men compete and even the way that men fight, the world will be quite a lot more dangerous and dark.

Brett: Yeah. The next question I was going to ask you is are there downsides? It seems like a lot of push. Everyone talks about we’re becoming softer and we’re afraid of that monkey dance and so we’re trying to do things to eliminate it almost. There’s talks of getting rid of football. There’s talks of regulating boxing even more and MMA even more. Are we opening up a Pandora’s box by doing that?

Jon: I think, arguably … One of the cool things I’ve read and, again, in the work with sociologists, is arguments for the re-institution of a dueling culture. For instance, in inner city neighborhoods or in prisons. We’re talking about specifically a culture of boxing duels.

The point is that what you have in an inner city neighborhood or many inner city neighborhoods and certainly in serious prisons are cultures of honor without dueling codes. If you are going to have a culture of honor, a culture where men are incredibly touchy about disrespect and willing to claim respect with physical violence, you don’t want to have that kind of honor culture without a dueling code because you have that kind of honor culture without a dueling code, then you get things like Hatfield-McCoy blood feuds. You get things like prison shankings. You get things like drive-by shootings.

The idea of a culture of boxing duels would be that it makes those other forms of violence dishonorable. You’re branded a coward and you have to eat a lot of shame if you go outside of the dueling code. So I think there’s at least an argument to be made that in certain situations, a re-institution even of dueling codes could be a good thing.

Brett: I just had a question but it left my mind. I wanted to hit the point. The big point here is ritual combat or ritual violence within humans and even animals. The goal is in to kill your opponent, correct, just to rough him up a bit.

Jon: That’s right. Normally, what happens with ritual combat among animals, for instance, is almost always it doesn’t come to a real fight because the animals will pose at each other back and forth, they’ll puff up, they’ll bluster and threaten each other. One guy will look at the other guy and say, “Hey, you’re bigger than me. You look like you’re fitter. I’m going to cede this territory to you.”

They only have a real fight if they’re very evenly matched. At some point, the weaker guy taps out. He’d say, “Okay. You win.” He backs out. That’s basically the way with people too. There’s systems built in where we’re able to determine who the better man is without having to fight it out to the death.

Brett: Got you. Your book is called Why Men Fight. What does the research say about why men are drawn to violence more so than women? Is it biological? Is it cultural? Is it a mixture of both? What’s going on there?

Jon: I think it’s largely biological. We’re animals. We seem to forget that. The stallion differs from the mare and the cow differs from the bull and the female chimp or gorilla or monkey differs from the male version. They differ not only in their bodies but they differ in their behaviors.

Why should it be different for us? Wherever you go around the world, you’ll never find a society where men don’t do the lion’s share of the violence. This is throughout human history. It’s across cultures. I mean, there’s literally never been a documented example where women did most of the fighting, where they did most of the warring and where they caused most of the social chaos in the group by causing fights within the group.

Human may have also been shaped by this evolutionary history of violence. It’s why men are bigger than women. It’s why men are faster. It’s why even in trained athletes, men have much higher cardiovascular capacity. It’s why men are stronger. And it also affected our behaviors, our psychologies. It’s why men are more physically aggressive. It’s why men are more prone to taking really idiotic risks and it’s why men are more willing to resort to physical forms of aggression.

Now, all that said, this isn’t to say that culture plays no role and it’s not say that everything about gender is biologically determined. But when it comes to these questions, the questions I’m looking at in my book, questions about violence, about intensely competitive behavior, about physically aggressive behavior, this is where the sex differences are at their most massive. It’s where the biological roots of those differences are least controversial.

Brett: The second part of your subtitle is why we like to watch men fight. Why is it? Everyone played that moment in high school where there’s going to be a fight after school. You go to some undisclosed location. Form the circle. You get really excited watching. You get the chills, right? You get the hair lift up on your … But it’s exciting. Why do we like to watch men fight?

Jon: That’s a great question and that’s a great example. That really brought me back to my own childhood. I think there’s at least a couple of answers to this. I started thinking about this really intensely as I was working on the book and as I was watching a lot of cage fighting.

I’d be thinking to myself, “I’m a civilized person. I’m a peace-loving person. I’m apparently not a sociopath so why am I watching this? What’s wrong with me? What’s wrong with this all?”

Even if you wouldn’t be caught dead cheering at a cage fight or a boxing match, almost certainly you consume a huge diet of violent entertainment in your movies, in your films, in your books, your video games and so forth.

This is an uncomfortable truth but I do think it’s the truth is that we all claim to hate violence, why we’re just stuffing it into our heads the whole times. We’re spooning it up saying that we hate the taste of it but the truth is that we seem to like violence. There’s a creature in us that likes violence, that like it more than just about anything else.

There’s other side of this, I think. When it comes to a fight, when it comes to a sport fight, I think what draws us in is not so much as the barbarism or the blood lust. I don’t know about you but I don’t ever want to watch an Isis torture/murder video.

Brett: No.

Jon: I don’t think most people want to watch it. I find it very hard not to watch men fighting. I think it’s because it’s such an incredibly intense drama. It’s such an incredibly intense spectacle and the men have so much riding on it and it’s real. It’s truly reality TV. A fight will set up these conditions of incredible adversity that allow the best elements of human nature to shine through.

We talk about things like courage and boldness in the strains of grace and endurance. I think I will sound that many people like an apologist for violence but, I think, what draws us into combat sport as viewers isn’t that were succumbing or reveling in the worst aspects of human nature. I think we go to a sport fight to honor and to celebrate the best aspects of human nature.

Brett: That’s what Joyce Carol Oates wrote about.

Jon: Yeah. She wrote a fantastic book. It’s really my favorite book about fighting, her book on boxing. Like all of us, she’s flopping around a little bit. She’s trying to figure it out herself. What am I doing watching this stuff?

I think she is even more ambivalent about it than I am. Ambivalent is the proper attitude by the way to a sport fight, I believe. I think we should be repelled by it. I think we should feel morally compromised by it to some degree. But there’s also something noble about it in my opinion.

Brett: You quoted William James, that is the Steeps. It’s like an anti-war essay but it’s basically making the case too if we didn’t have war, we lose those chances to display nobility and courage and basically.

Jon: Yeah. Steeps of Life is a great line. Once I read that line, I’m like, “That’s what we’re after in mixed martial arts.” Young guys who are a little bored of the flats of life, of these flat roads, of the softness and ease of life and they want the steepness, they want this challenge, they want this Everest to climb. That’s the kind of quest that I was talking about.

Brett: I’d like to get your opinion on this after going through this whole experience. Are you still training Mixed Martial Arts? Do you still go to the gym?

Jon: I expected to train for a year, have a fight and quit. I continued training for another two years afterwards and then I had to give it up basically because I was just too beaten up. I dibble back in now and then a few months. I get itchy for it and miss the guys. I go in but I’m not just holding up to it physically like I used to.

Brett: Yeah. It sounds like you developed a really great camaraderie with these guys.

Jon: Yeah. There’s something weird that happens. This was one of those things that I just wouldn’t have known if I hadn’t done it but there’s something about a sport fight and about sparring in particular that really draws guys close together.

One of the lines I wrote in my Mixed Martial Arts diary that I wrote in every night after training was that there’s this weird paradox that nothing makes men love each other as a good-natured fistfight. It’s true.

That was one of the hard things about giving it up. I was giving up the physical challenge of it but I was also losing my peer group.

Brett: I call it aggressive nurturing. It’s what guys do.

Jon: Yeah. I think it’s right. I call it this weird pathetic alchemy whereby guys transform aggressive words and aggressive actions into terms of endearment, you know? I punch you in the shoulder. It’s violent but it means I love you. I call you some name but it means I care for you. You know what I mean? It’s this weird process of translation that men are able to automatically translate. Whereas, I think women are what … what, are they mad at each other?

Brett: Yeah. They shouldn’t do that. Stop that.

Through your experience, your training … We live in a society where effectively we’ve outsourced protection to the state. We have the police officers. We have a military that 1% of the population serves in. For the most part, society is safe. It’s not a very violent world despite what the news says, at least in the United States.

Is there any reason a man should be capable of fighting and being tough and strong? Should a man strive for that for any reason?

Jon: It’s a good question. I guess there’s a couple of ways to look at it. First off, I’m 40 years old. I live in a suburb middle class. Violence is less and less likely to occur to me. I’m most likely to get into a monkey dance with somebody. I don’t cross paths with violent men on a regular basis. But not everybody lives in a neighborhood like I live in, you know? For young guys especially, it’s much more likely that you find yourself in these monkey dancing situations.

I feel like there’s still a rule for self-defense, practical self-defense but, I think, more than that there’s a self-respect angle to it, don’t you think?

Brett: Yeah.

Jon: I think that whether or not you’re going to be violent or face situations of violence, still in order to respect yourself as a guy, you want to be able to feel that you’re capable of handling yourself. You’re capable of defending yourself and defending the people that you love and care for.

I do think that there’s a sort of … I don’t know … We’re less likely to need it, it still is a part of our makeup, to want to be able to handle ourselves.

Brett: Got you. I agree completely with that sentiment. Through your training at MMA, did you find that it provided benefits in other areas of your life like it was a carry-over?

Jon: Yeah, I do. Part of what I was after was self-respect. Part of my own personal history of violence but I’ve never been in a fight and I had dodged quite a few fights in my adolescence and it’s weird how much psychic weight that put on me.

Even as a 40-year old, I’m still able to look back at how I behaved when I was an undersized 15-year old getting pushed around by bullies and still have the power to feel me with shame. Weirdly, man. Weirdly.

All I’ve accomplished, the things I’ve done, they matter but still that stuff makes me blush. There was carry-over. I wanted to know whether or not I was a coward. I wanted to know if I was capable of doing something brave. For me, getting into the cage and fighting, was scary and it did take bravery. I was able to prove to myself that I’m not the bravest guy in the world or toughest guy in the world or anything like that, not even close, but I was able to do what was for me a brave thing.

Brett: Would you recommend other men do this?

Jon: The Dutch translation of my book, the title, that they didn’t consult me on at all is called Real Men Fight which is a horrible title. I’m not saying that in order to be a real man, you have to fight. I’m not suggesting that every guy, in order to feel like he is truly masculine, have to be a trained killer.

I think a lot of guys are attracted to it. We watch Bruce Lee movies as kids, Jean-Claude Van Damme movies and we’ve wanted to be that guy. For guys who are interested in it and do lean in that direction or wondered about it, I would definitely recommend doing it.

I think the main reason people don’t do it more often or most guys don’t do it more often is because they’re afraid of it. They’re afraid of the violence. They’re also afraid of walking into the gym for the first time and what it’s going to be like. I know that because I was too and everyone who was in the gym for the first time is scared but if you go in, you’re not going to get beaten up on the first night. You’re not going to get strangled to death on the first night.

It’s a pretty nice and nurturing atmosphere. Yeah, I recommend it. I mean, in fact I’m going to say one more thing. There’s a political scientist who have this little phrase that I liked and he had visited West Point, the military academy at West Point.

He described West Point as a little taste of Sparta or a little touch of Sparta in the midst of the American Babylon. We had a society that is sort of … I don’t know … It’s soft and it’s all iPhones and Twitter and consumerism and then you go into the MMA gym and it’s very gritty and it’s very real. You’re doing things that are very gritty and very real. You’re back in Sparta. Your friends are in a warrior band and you’re working to make each other tougher and stronger. You’re cooperating and beating the fear and the timidity out of each other.

It was just a really positive experience for me. I have a bit of a convert zeal for MMA. I recommend it to everybody if you’re interested. But if you’re not interested, I understand that too.

Brett: Sure. This has been a fascinating discussion. We really did just scratch the surface of what’s in your book. Where can people find out more about your work and about the book?

Jon: They could Google me. I have my website. It’s Jonathangottschall.com. Or, they can just Google me.

Brett: Great. I’m going to check that out. Jonathan Gottschall, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Jon: Thanks for having me on. I really appreciate it. I am a big fan of the whole Art of Manliness Project.

Brett: Thank you. My guest, Mr. Jonathan Gottschall, he is the Professor of the book The Professor in the Cage. Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch. You can pick it up at amazon.com. I recommend you go out and get it. It is, again, one of the best books about masculinity I’ve read in a while. Really, it’s got a great story because you get to see what happens to him when he finally fights and enters the cage. Go and check it out on amazon.com, the Professor in the Cage.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you’ve enjoyed our podcast, I really appreciate if you go to iTunes or Stitcher or whatever it is you use to listen to the podcast and give us a review. That would really help us out a lot. Also recommend us to your friends. It’s one of the best compliments you could give us.

Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.