Minimalism is a lifestyle/movement that’s been around for centuries, and waxes and wanes as part of the cultural zeitgeist. Several years ago it resurfaced in a big way. Blogs about being zen and simple living rocketed up in popularity, and people started taking the “100 Thing Challenge.”

Minimalism has even been touted a couple times on this very blog, and I really like the idea of it as a whole. There is something very inspiring about living Spartanly, and there are some definite benefits to doing so. It helps you not get caught up in the consumerism trap, and keeping your life free of excess stuff unburdens your mind from that weight, allows you to be mobile and travel light, and helps you save money and focus on that which is really valuable.

But, it’s one of those things that can be taken too far. Despite a desire I sometimes get to embrace minimalism wholly, there have always been a few things that have made me uncomfortable about it:

Strict minimalism is largely for the well-off…

What first got me thinking more critically about minimalism was an article I read a few years back in the New York Times, which begins thusly:

I LIVE in a 420-square-foot studio. I sleep in a bed that folds down from the wall. I have six dress shirts. I have 10 shallow bowls that I use for salads and main dishes. When people come over for dinner, I pull out my extendable dining room table. I don’t have a single CD or DVD and I have 10 percent of the books I once did.

The author of the piece, Graham Hill, then goes on to explain how his current lifestyle is a big departure from how he had formerly carried on. Having come into a huge windfall after selling an internet start-up in the 90s, Hill indulged in big-ticket purchases and found his life inundated with stuff. That all changed when he fell in love with a woman from Andorra, and he packed his possessions in a backpack to follow her around the world. By traveling light, he was able to reevaluate his relationship with mere stuff, and now intentionally lives “small.”

I both enjoyed Hill’s story and felt bugged by it, and I couldn’t figure out the reason for my latter reaction until I came across a little essay by Charlie Lloyd:

Wealth is not a number of dollars. It is not a number of material possessions. It’s having options and the ability to take on risk.

If you see someone on the street dressed like a middle-class person (say, in clean jeans and a striped shirt), how do you know whether they’re lower middle class or upper middle class? I think one of the best indicators is how much they’re carrying.

Lately I’ve been mostly on the lower end of middle class (although I’m kind of unusual along a couple axes). I think about this when I have to deal with my backpack, which is considered déclassé in places like art museums. My backpack has my three-year-old laptop. Because it’s three years old, the battery doesn’t last long and I also carry my power supply. It has my paper and pens, in case I want to write or draw, which is rarely. It has a cable to charge my old phone. It has gum and sometimes a snack. Sunscreen and a water bottle in summer. A raincoat and gloves in winter. Maybe a book in case I get bored.

If I were rich, I would carry a MacBook Air, an iPad mini as a reader, and my wallet. My wallet would serve as everything else that’s in my backpack now. Go out on the street and look, and I bet you’ll see that the richer people are carrying less.

As with carrying, so with owning in general. Poor people don’t have clutter because they’re too dumb to see the virtue of living simply; they have it to reduce risk.

When rich people present the idea that they’ve learned to live lightly as a paradoxical insight, they have the idea of wealth backwards. You can only have that kind of lightness through wealth.

If you buy food in bulk, you need a big fridge. If you can’t afford to replace all the appliances in your house, you need several junk drawers. If you can’t afford car repairs, you might need a half-gutted second car of a similar model up on blocks, where certain people will make fun of it and call you trailer trash.

Please, if you are rich, stop explaining the idea of freedom from stuff as if it’s a trick that even you have somehow mastered.

The only way to own very little and be safe is to be rich.

Basically, minimalism is largely something only well-off people can afford to pursue, because their wealth provides a cushion of safety. If they get rid of something, and then need it later, they’ll just buy it again. They don’t need to carry much else besides a wallet when they’re out and about; if they need something, they’ll just buy it on the fly. No sweat. If you’re not so well-off, however, having duplicates of your possessions can be necessary, even if such back-ups ruin the aesthetics of owning just 100 possessions.

…and philosopher bachelors.

It is true that there have been exceptions to this rule throughout history — men who have been both intentionally poor and dedicated minimalists. They simply do not care for possessions, or what will happen to their bodies if they lose them; if they have to live on the street and beg for their supper, so be it. Certainly there is something inspiring about this kind of commitment, but it comes with a couple caveats.

First, these men have almost invariably been bachelors – philosophers, monks, spiritual teachers, and the like. Still today, the vast majority of lifestyle design gurus and minimalist converts are men without children.

Now people can debate all the day long about whether this is perhaps the way every man should go – holding on to the freedom to do whatever you’d like, indefinitely. But for those who are immovable in the conviction that family constitutes the greatest happiness in life, strict minimalism becomes, if not impossible, then highly undesirable. I could have my children sleep in a cardboard box and use a twig as a teething toy, but there are a good number of accouterments that make rearing one’s rugrats infinitely easier.

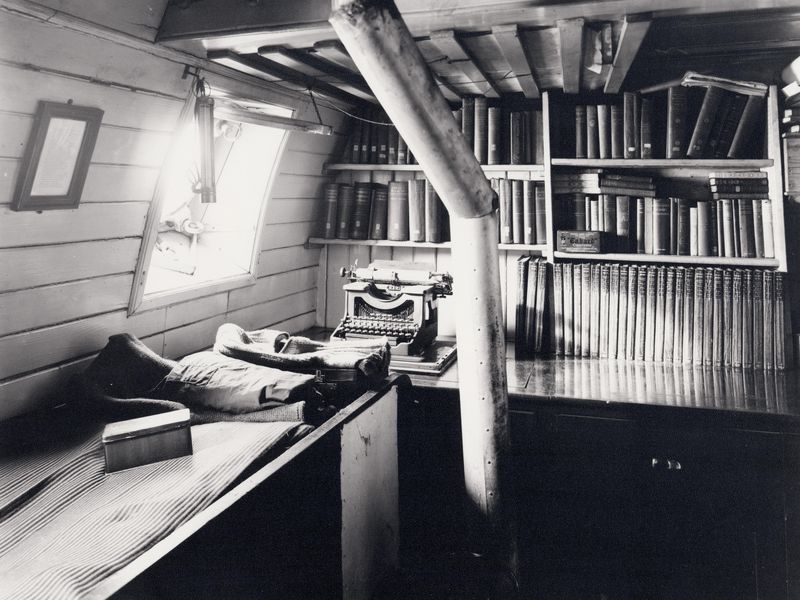

Second, the ranks of even history’s most supposedly hardiest minimalists are fewer in number than legend might have us believe. For just one example, Henry David Thoreau is often looked to as the high priest of minimalism (“Simplify, simplify, simplify!”). While he did indeed live sparsely while at Walden Pond (though his family often brought him meals), he spent most of the remainder of his life occupying the attic of his parents’ comfortable, well-appointed home! He enjoyed quite the safety net. So too, he amassed a large collection of both books and natural specimens that cluttered his living quarters, and he took much joy in these collections.

Minimalism still makes stuff the focus of your life!

The great irony of minimalism is that while it purports to free you from a focus on stuff, it still makes stuff the focus of your life! The materialist concentrates on how to accumulate things, while the minimalist concentrates on how to get rid of those things…ultimately they’re both centering their thoughts on stuff. It’s like a compulsive overeater and a bulimic. One thoroughly enjoys eating, and stuffs his face whenever and wherever he can. The other eats, hates himself for eating, and then purges it out. But they’re both obsessed with food. The satisfying “high” one gets from decluttering has always struck me as a little unsettling (though I experience it myself!); you accumulate stuff, and then revel in purging it out of your life, only to quite often repeat the cycle once more. What a weird First World phenomena.

A Moderate Minimalism

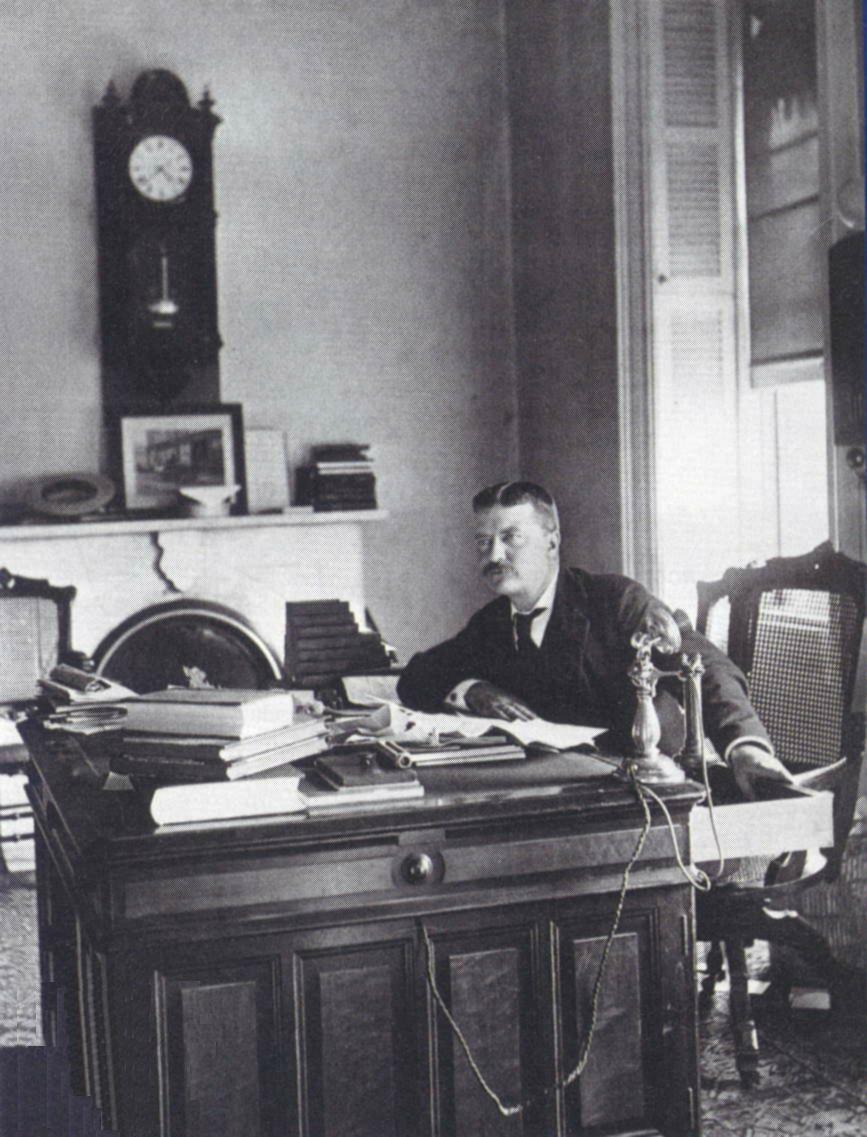

As I said at the beginning, I think minimalism is a great thing, just not when taken to extremes. A man should have a healthy relationship with his possessions, and that means getting into the right mindset about them, and then not thinking about them very much at all. Most of the great men I admire from history knew what they needed and enjoyed (check out their libraries and studies). They accumulated things that were both practical and simply brought them pleasure. They bought things that were well-made and wouldn’t have to be replaced over and over. They didn’t hoard or surround themselves with junk. They didn’t go overboard and stretch their budget to keep up with the Joneses. And they didn’t have to make a philosophy on stuff central to their lives, because they had too much else going on to need it. They didn’t have time to worry if 103 possessions might be too many, if their huge library of books should be reduced, if their studio full of art supplies was too cluttered, or if a room dedicated to hunting trophies might be weighing down their psyche. But they were minimalists where it mattered: in paring down the time-wasters and soul-suckers that would hold them back from creating a rich, manly legacy.