This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction-free book to read offline at your leisure. Available as an ebook or a paperback.

Everyone loves a good, clear, easily grasped narrative. “X leads to Y.” “A causes B.”

But as we’ve seen over the course of this series, the nature of depression is simply too complex to follow a nice, neat storyline.

In exploring the history of depression, we saw that the way we view melancholy today is not how it’s always been seen, and that the condition has in fact been understood in widely different ways over the centuries.

In our discussion on what causes depression, we demonstrated that our modern theories are no more clear-cut, and that because melancholy results from the interaction of several different factors, we’ll likely never be able to precisely pin down its origins.

Finally, we saw that there isn’t a bright line that distinguishes “normal” sadness from clinical depression, and that being diagnosed with the latter remains a somewhat subjective call.

Now, as we finish this series, we must challenge two final narratives:

“Depression is entirely the person’s fault. They just need to sack-up and snap out of it.”

“My depression is not something I can control. I am a victim and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

The first narrative is popular amongst those who have never experienced depression; the second amongst those who feel like they’re losing their battle with it.

Each narrative contains a kernel of truth, but each is also grossly simplistic.

Managing one’s depression involves rejecting these easy storylines in favor of navigating a far more nuanced approach between them.

You have to be compassionate but honest with yourself. You have to accept that which you can’t control, and take action on what you can. You have to take depression seriously, without letting its gravity crush you. You have to mitigate its negative effects, while allowing for some positive to come out of it.

Walking this line isn’t easy; sometimes you’ll be too hard on yourself for your failures, and sometimes you’ll wallow in self-pity over the stubbornly melancholic disposition you’ve been handed.

As an aid in your journey, we have provided the following guidebook on how to successfully navigate depression. It’s packed with accessible, research-backed, field-tested action steps, examples from the lives of great men who dealt with depression, answers to frequently asked questions, and even a few tips for the friends and family of the depressed. You’ll learn how to transform your mindset and adopt practices that will allow you to temper depression’s ill effects, harness its more positive attributes, and help you take a more stable, confident stance towards dealing with periods of deep melancholy.

This is not a detailed prescription, but a roadmap. Everyone is different, so what works for you might not work for someone else. I strongly encourage you to experiment and find the practices and habits that are most effective in managing your depression.

Some of what follows reviews important points from previous articles on the general nature of depression. But new insights and angles have been brought to bear on them, and it’s important to read everything in this context of how they practically apply to tackling one’s own melancholy. So I implore you to read this guidebook in its entirety. Do not think of it as a long blog article, but as a short ebook. Take it one section at a time if you need to, but commit to finishing it. I don’t think you’ll find it an unenjoyable read.

With that introduction out of the way, let us now dive into how to take the bull by the horns, and the black dog by the leash.

The obligatory disclaimer: While I have a lush head of hair that would qualify me to play a doctor on a soap opera, I am not a physician, psychologist, or psychiatrist. I’m a guy who went to law school, never took the bar, and blogs about manliness for a living. The recommendations in this article represent the best advice I have culled from the massive amount of research I have done on depression, as well as the practices that have worked for me personally. It should be used for informational purposes only; if you have any concerns, need additional advice, or are suicidal, please talk to a mental health professional.

The Foundation: Change Your Perspective of Depression (and Happiness)

Before you get started proactively managing your melancholy, you first need to work on re-shaping your perspective of it, as well as your expectations for what your recovery from depression will look like. Self-defeating beliefs and unrealistic goals can set you up for failure before you even get started.

Change Your Mindset on the Nature of Your Depression

Understand that depression is natural.

Depression has been around for thousands of years, and has been viewed in very different ways over that time. These days we see it as a sickness and disease — a foreign invader that must be “cured” straightaway. The intentions behind this framework are worthy; by comparing it to a physical malady, little different than something like diabetes, some of the stigma surrounding mental illness is removed. The sufferer cannot be blamed for bringing the condition upon himself.

But this perspective also comes with serious downsides. A disease is something you have no control over; its presence makes you a victim. So too, it makes depression an unmitigated bad, a boogeyman out to destroy your soul.

For these reasons the idea of depression-as-disease can lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. When the black dog arrives at our door, we are sore afraid and sink deeper into feelings of anxiety and despondency.

Better, I think, would be to view depression as something natural, part of the ebb and flow of life. These days we’re expected to be growing and progressing all the time. But the human organism also needs periods of retreat and compression. The frequency for which you need such times of rest and consolidation, and the severity of the consequences when you don’t get enough, is part of what gives you a more or less melancholic temperament.

Your need for periodic retreat is largely due to factors outside your control — genetics, upbringing, etc. But while we can’t completely control our susceptibility to depression, we can learn thow to manage it — getting out of funks quicker when we fall into one, taking action to stave off future bouts, and working to mitigate its ill effects while harnessing its positive ones.

In other words, rather than trying to kill the black dog outright, we should try to leash it.

Understand that depression has both drawbacks and benefits.

Many of our forebearers, rather than seeing depression as wholly bad, believed that a melancholic disposition was just one of several possible innate temperaments, each with their unique assets and drawbacks.

The downsides of depression are well-known: social withdrawal, a lack of interest in activities, numbed emotions, insomnia, irritability, and so on.

Less talked about are depression’s possible benefits, so let’s explore them:

The ability to accurately assess the world through the lens of “depressive realism.” Research shows that melancholic individuals are better at accurately assessing and analyzing their environment, as well as sussing out potential threats. This makes them well-suited for jobs in which a hard-nosed, pessimistic outlook is a boon. A perfect example is the legal field; lawyers need to be able to figure out all the potential downsides, vulnerabilities, and liabilities of deals and cases. I honestly feel that my melancholic temperament helped me succeed in law school. I continue to drive Kate (who has a naturally optimistic disposition) crazy with my insistence on pointing out the possible pitfalls of this or that decision — an innate impulse that was only heightened by my law school days. But, it really takes both types of people to make the world go.

(As a side note: it’s often quoted that lawyers are statistically more likely to be depressed than non-lawyers — 3.6X more, in fact. This is usually chalked up to the apparently soul-sucking nature of the job. But it also could simply be that people who are already prone to depression, decide to become lawyers.)

Looking at the world through the lens of “depressive realism” may contribute to my success in running the Art of Manliness as well. Readers have told me that they appreciate the way AoM steers clear of the kind of pie-in-the-sky, follow-your-bliss, self-help/lifestyle design messaging that is popular these days, and instead offers more down-to-earth, realistic advice.

Depression lends you a single-minded focus. Depression drives a person to withdraw socially and break off from their normal activities in order to ruminate on things somewhat obsessively. If the object of that single-minded focus is the person’s gloomy mood, the effect is wholly detrimental. But if a melancholic individual can channel their thoughts towards a purpose outside of themselves — a public issue that needs tackling, a mathematical equation that needs solving, a novel that needs to be brought to life — they can make significant contributions to the world. Many great men from history, from Charles Darwin to Henry David Thoreau to Winston Churchill, suffered from melancholy, but used it to drive their work and accomplishments.

Depression tends to make you something of an “old soul.” Those who suffer from depression are inclined to retreat from the world to their home cave, and are thus often more grounded and settled than some of their more flighty peers. Melancholic individuals are also prone to introspection, which produces a depth and seriousness — a certain gravitas — in them that’s lacking in the perennially sunny. Having suffered acutely, they can gain wisdom and insight on the human condition and may have greater empathy for the struggles of others. Their world-weariness is something people paradoxically feel they can rest in. That is to say, it is often easier to confide in a melancholic man, and trust he may have some advice for you, than it is a hyper-cheery, everything’s-awesome kind of dude, who may not really get why you’re having a hard time, and brushes off your concerns with a shrug and a smile.

This all isn’t to say one type of person is better than another; again, different temperaments have different strengths and weaknesses.

So too, I don’t wish to paint too rosy a picture of a very serious and severe condition that can reach the point of having absolutely no benefits at all. Many artists have harnessed the wisdom-imparting, insight-producing side of melancholy to create some of the greatest paintings and books in our cultural canon. But, some of them also eventually killed themselves.

Even if one’s depressive symptoms don’t drive them to suicide, they can certainly be challenging to deal with. If some people live in a perennial spring, melancholics reside in an eternal winter: it takes more work to get out the door and find activities to enjoy; it’s more difficult to stay in a relaxed and positive state of mind; life just feels harder all around.

Thus, the takeaway here is to accept your melancholic temperament, but to realize it will take hard, intentional work to harness and keep in check. You have to learn to make the most of it, instead of letting it get the best of you.

Change Your Mindset About “Curing” Your Depression

Manage your expectations about “recovery.”

When I had a conversation with psychologist Jonathan Rottenberg, author of The Depths, he mentioned that therapists and doctors don’t manage expectations for recovery very well when dealing with depressed patients. For some reason, a lot of people have this idea that as soon as they begin taking medication or doing therapy, their depression will lift, and it’ll be gone for good. When their recovery doesn’t go as expected, these folks just sink further into a funk.

As someone who’s seen family members deal with depression all my life and has battled the black dog personally, I can tell you that “recovery” from a major episode looks a lot different than the rosy expectations that are often doled out by doctors and drug companies. It’s slow and usually underwhelming. It took me several months before the gray clouds started lifting from my first significant depressive episode. And when the skies did start abating, I didn’t suddenly feel exuberantly happy and positive all the time. I just didn’t feel depressed. Color came back into my life gradually, rather than all at once.

So as you start your journey in leashing your own black dog, keep your expectations reasonable. Don’t expect quick fixes or that you’ll be filled with inexhaustible vim and vigor once your symptoms start decreasing. Having unrealistic hopes will just set you up for a demoralizing disappointment that may spiral you deeper into depression.

Another thing to keep in mind is that even when you get a handle on your depression, you’re still not out of the clear. Research shows that if you’ve experienced one major depressive episode, your chances for another increase.

If you’re someone with a generally melancholic temperament, even when you’re not clinically depressed, then you’re probably more likely to have a relapse down the road. If you’re usually a sunny, optimistic guy, but sunk into a funk because of some life event like the loss of a job or the death of a loved one, your chances of becoming depressed again are likely lower.

Understand that there is no single magic bullet.

Another of the problems with our modern pharmaceutical-therapeutic approach towards depression is that various “cures” are often portrayed as “magic bullets”: “Take this pill and your symptoms of depression will lessen.” “Just a few weeks of therapy will help you start feeling better.” But as we’ve seen, depression is a Hydra-headed beast that is caused by several factors, intermingling in complex ways. Consequently, there’s no silver bullet that will single-handedly stop the monster in its tracks.

Instead, you have to take a holistic, multi-faceted approach that includes shifting your mindset and adopting healthy lifestyle changes. And yes, it may also involve therapy and medication. Everyone is different, so some things will work for you and some things won’t. Be ready to experiment.

Understand that your maintenance program will last indefinitely.

Keeping the black dog at bay takes constant practice and effort. There’s no “one and done” here. You have to give focused, intentional effort every single day. You’re going to have to be a lot more proactive than naturally happy people are about staying on track with your healthy habits. When you’re in the depths of a deep depression, giving that kind of effort can be hard. But you’ve got to do what you can. There’s simply no finish line with depression.

Accept you may never be as chipper as your peers.

If you’re a generally upbeat guy who’s suffering a bout of depression, you’ll likely go back to being an upbeat guy once you pull out of your funk.

But if you’ve always been a little gloomy in temperament, even if you get over a hump of clinical depression, you may never be as chipper as some of your peers. While I haven’t suffered a major bout of depression in several years, I’m still not an effusively cheery person. And I never have been. By and large I’m a happy, content, satisfied, stable, grounded, and well-functioning guy. I laugh, joke, and enjoy life. But no one would ever accuse me of having a sunny disposition; lesser waves of melancholy still come and go, and I can be moody, peevish, and curmudgeonly. I don’t think that will ever change. And realizing that has actually made a huge difference in helping me cope with my black dog.

For more than a decade I felt that if I could finally find the right combination of tools/philosophy/supplements then I’d magically become a perennial ball of sunshine. That I hadn’t yet been able to accomplish this feat made me feel like a failure.

I finally accepted the fact that there’d never be a time when I could ultimately say I had “cured” or “overcome” my depression, and that I’d never be that cheery, upbeat guy. And that was okay; I made peace with my inherently gloomy temperament. While such resignation might seem, well, depressing, continually kicking against the pricks actually made me more miserable. Accepting I was never going to slay the black dog, but rather could only leash him, freed me to concentrate on the far more reasonable goal of mitigating my melancholy. Rather than endlessly looking for new “cures” to try, and flagellating myself that they hadn’t “worked,” I could simply concentrate on making generally healthy practices more of a habit.

I actually became happier by giving up on being happy…at least in the way we currently define it…

Note to the loved ones of a depressed individual: It’s not just important for the depressed to manage their expectations about their condition, but for you to do so as well. If you’re a naturally sunny person, and you use your own temperament as the baseline for normalcy, you’ll be perennially waiting for your loved one to finally “overcome” their melancholy and become “normal” just like you. Each time they fail in doing so will bring you a fresh set of disappointments. You’ll get your hopes up about each new “cure” they try, only to have them dashed. Your frustration may erode your trust and respect for them; “If they really wanted to change,” you think, “then they could.” This is surely a recipe for strain in your relationship. Instead, make a deal with your loved one: if they do what’s in their power to manage their depression, you’ll accept that being melancholic is a legitimate, innate temperament that cannot be fundamentally altered.

Change Your Mindset About What It Means to Be Happy

Happiness is a word that gets thrown around a lot these days. Seems like there’s always a new blog post or book coming out promising tips on how to attain it. Typically, they talk about “happiness” in terms of “feeling good” and offer strategies on how you can feel good more often and make those good feelings last.

The problem with this definition of happiness is that its goal is something that is invariably fleeting; feelings and emotions come and go like a summer breeze.

As such, when people, especially those who are not constitutionally cheery, try to be “happy,” they can feel like they’re failing, like they’re trying to catch lighting in a bottle and just can’t get the fluorescently bright feelings to stick around.

Which is why I suggest you swap the modern concept of happiness as “feeling good” for the definition favored by the ancient Greeks. In antiquity, happiness, or eudaimonia, meant living a flourishing life. The classicist Edith Hamilton said the Greeks described flourishing as “the exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence in a life affording them scope.” In layman’s terms, a flourishing life was one in which a person practiced virtue and maximized their potential by striving in worthy pursuits. Happiness was not a flighty feeling, but the sense of satisfaction that comes from reviewing one’s effort each day, week, month, and year. It was for this reason that the Greek sage Solon offered this admonishment: “Count no man happy until the end is known.” “Happiness” was a life-long project.

Since it’s not a feeling that comes and goes, happiness-as-flourishing is more concrete and within an individual’s control; even those predisposed to melancholy can achieve it. Flourishing requires you to strive for excellence not only in the big things in life, but also the mundane. Every moment is both a challenge and an opportunity. Within this framework of happiness, it doesn’t matter if you’re not bubbling with enthusiasm, so long as you’re working to be a little bit better in everything you do.

But here’s the interesting thing. As you focus on taking action to be better — to flourish — you put yourself in a position to experience more “feel good” happiness, too. “Joy, like sweat, is usually a byproduct of your activity, not your aim,” writes Eric Greitens in Resilience.

Feel-good happiness won’t come all the time, so don’t expect it to, but enjoy it when it pays a visit. Soak it in. Relish it. But then get back to working on living a life of excellence.

An Ongoing, Action-Oriented Approach to Depression

One of the theories as to why women get depressed more often than men is that women have a greater tendency to ruminate about their feelings, which, as we’ll discuss below, actually makes people feel worse rather than better. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to distract themselves from their low moods by engaging in activity. This action-oriented approach alleviates depression more effectively than brooding.

Unfortunately, because women are more likely to suffer from depression, descriptions of its symptoms, as well as proposed cures, have tended to be female-oriented; the focus is on the symptoms of one’s mood and the need to talk it out. And because our whole culture has been influenced by modern psychological theories, even men now frequently see depression through this “therapeutic” lens.

So part of learning to manage your depression will actually be getting back in touch with your innate disposition to deal with it through action rather than rumination or talking. Certainly, thinking through your issues and talking to others can be healthy…in moderation. But brooding and long conversations won’t ultimately pull you out of a dark place, nor strengthen your defenses against future visits of the black dog.

Instead, the path to leashing your melancholic canine must be paved with action. Not just any action; distracting yourself with alcohol, internet surfing, porn, etc., ignores depression’s root causes and will simply leave you weaker and more vulnerable than before. What’s needed is the intentional pursuit of healthy, vigor-inducing, mood-boosting actions — filling your life with so much good stuff that melancholy won’t have much space to reside. This is the approach many eminent men in history who wrestled with the black dog took — often with gusto. For example, William Manchester observes of Winston Churchill: “Perhaps, as [his daughter] Mary says, his painting, writing, and manual labor ‘were sovereign antidotes to the depressive element in his nature.’ If so, never was depression so thoroughly routed by activity and wit.”

(An action-oriented approach will be most effective for women too, by the way, but they may have more of an uphill climb in fighting against their inclination to ruminate.)

These life-restoring actions are to be undertaken not simply when you are in the midst of depression, but when you’re feeling good as well. In fact, they are easiest to adopt when things are copacetic, since depression saps your motivation and drive. By making healthy practices a matter of habit — and nearly automatic — during your good times, you’ll have already “greased the groove” and made it more likely you’ll stick with your routine during your low times.

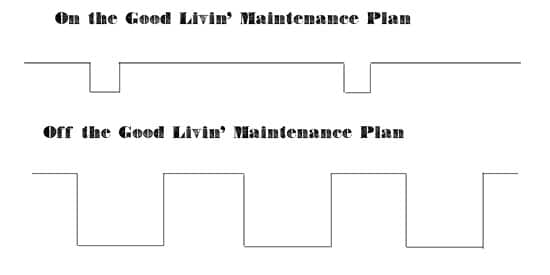

Adopting a healthy, good livin’ lifestyle won’t make you immune to depression. But you’ll live continuously on a higher plane of existence, your bouts of melancholy will come around less often, and they’ll be less deep and paralyzing when they do. You’re far less likely to fall into a dark chasm that takes months to climb out of.

Making a habit of healthy practices won’t make you immune to bouts of depression; if you’re disposed to it because of genetics or other factors, you’ll always be vulnerable to waves of melancholy. But, it will strengthen your resistance to the black dog, so that he comes around less often, and the low spirits he brings become far less severe. Depression’s effects then become more of a nuisance than a paralyzing, life-sucking force.

The Action Steps: A Two-Pronged Strategy for Managing Depression

When it comes to the many theories as to what causes depression, I personally subscribe to that of evolutionary psychology. The idea is that depression developed as a survival adaption that may have acted something like an early warning system that alerted the sufferer that they weren’t on the right path, that the environment they were in was threatening, or that they needed to change certain detrimental behaviors. A low mood was a signal that one needed a time-out to lay low and analyze the root problems at hand.

Unfortunately, our modern go-go-go market society doesn’t allow for any downtime, nor does it encourage healthy, introspective analysis. You’ve got to keep marching with a rock in your boot, even though it’s making every step painful.

At the same time, our current environment represents an acute mismatch with how we used to live for thousands of years; our isolated, stress-filled, sedentary lives have heightened the negative effects of depression.

Thus, you’re left with two problems: 1) an environment that deepens depression’s shadow side, and 2) a lack of space/time to utilize depression as intended to figure out where you’re getting off track.

One’s approach to managing depression must then also be dual-pronged and consist of: 1) adopting a lifestyle that hews closer to that of our ancestors and thus mitigates melancholy’s ill effects, and 2) carving out ways to make depression as constructive and generative as possible.

Overcoming Depression’s Catch-22: How do I motivate myself to take action to alleviate my depression, when my depression saps my motivation?

One of the most frustrating things about trying to alleviate depression is that it puts you in such a passive state that it makes it difficult to do the very things that will help you alleviate your depression.

That’s why you can’t wait until you “feel like” taking action before you do it. You just have to do it. Once you take that first baby step, you’ll immediately start to feel just a bit better. That will make you a little more motivated to take more action, and it’ll soon turn into a positive cycle that puts you on the way to mitigating your melancholy. You just have to take that first step.

I know that can be easier said than done, though. One thing that helps me take action whenever I’m in a depressed funk is to break down bigger tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. So if you’re having trouble getting started with meditation, tell yourself, “just close your eyes for one minute.” That’s much more manageable than trying to get motivated to start a 10-minute session (or longer), so you’ll actually follow through on the impulse. If getting out of bed seems impossible, just focus on moving your toe. After that, move your foot. After that, move your leg, and so on until you’re out of bed.

Another useful tip is to tell someone to nudge you when you start sinking into depressed passivity. For example, as we’ll see below, socializing can help lift our moods, but for most depressed individuals, socializing is the last thing they want to do. So tell a friend, “Look, I’ll probably tell you I don’t want to hang out, but just ignore me and come over. It will do me some good.”

If you’re so severely depressed that the smallest actions seem impossible to undertake, antidepressants may be the thing you need to get going. (See “Should I Take an Antidepressant?” below.)

Ultimately, whether you’re on medication or not, taking the first step to getting better is something you’ll have to just dig down deep and force yourself to do. As Joshua Wolf Shenk, author of Lincoln’s Melancholy, puts it:

“When a depressed person gets out of bed, it’s usually not with a sudden insight that life is rich and valuable but out of some creeping sense of duty or instinct for survival. If collapsing is sometimes vital, so is the brute force of will. To William James we owe the insight that, in the absence of real health, we sometimes must act as if we are healthy. Buoyed by such discipline and habit, we might achieve actual well-being…In the small battles of life, brushing one’s teeth, taking a walk—these can be movements in preparation for victory.”

Depression Management Prong #1: Mitigate the Negative Effects of Depression by Reviving the “Old Ways” of Your Ancestors and Making Healthy Lifestyle Changes

Depression is practically non-existent in hunter-gatherer tribes that still live as our forebearers did for thousands of years. They experience the natural emotional ebb and flow of life, including low moods, but the ancient habits they continue to practice have a protective effect that keeps the severest symptoms of the black dog at bay.

You don’t have to reside in a grass hut to enjoy these protective benefits; you just have to live as a 21st century man who honors some of the old ways of his ancestors.

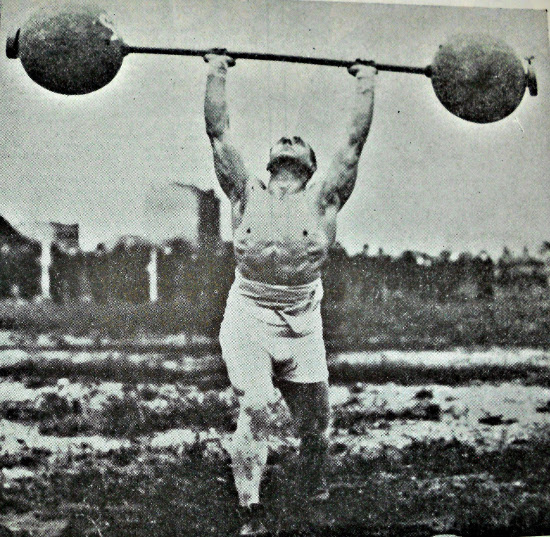

Exercise

If you implement just one piece of advice from this article, let it be this.

You need to exercise. Regularly. From now until you give up the ghost.

If you struggle with depression, but aren’t regularly working out, you haven’t begun to fight.

This isn’t rah-rah cajoling; it’s a research-backed truth.

Numerous studies have proven that exercise is just as effective as antidepressants in treating depression. Research has also shown that people who exercise are about 3X less likely to relapse into depression over the course of a year, than those who take medication alone.

And of course, unlike drugs, exercise is free, and its side effects are 100% positive.

Exercise’s antidepressant effect is thought to be a function of the way in which it boosts endorphins — a natural painkiller and mood booster. It also increases norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that may enhance mood. Plus, exercise stimulates the growth of new brain cells, which counteracts depression’s neuron-retarding and brain-shrinking effects.

Exercise also has more intangible benefits — increasing confidence, discipline, and willpower, and fostering the satisfaction that is born of using one’s body as it was intended — to move, work, push, run, jump, and lift.

Studies show that the more vigorously you exercise, the more depression-destroying benefits you accrue. Aerobic exercise seems to be particularly effective in boosting mood, but weightlifting has its unique satisfactions as well. I’d recommend doing both. Aim to work out for 45-60 minutes at least 3-5 times a week.

If that seems like too much to implement, know that simply walking vigorously for 45 minutes 3X a week has been found to have depression-squashing effects.

And if you can’t even motivate yourself to start walking? Take a page from a college student who was interviewed for an Atlantic Monthly article about exercise and depression and adopted the baby steps approach we recommended above:

“He thought getting some exercise might help, but it was hard to motivate himself to go to the campus gym.

‘So what I did is break it down into mini-steps,’ he said. ‘I would think about just getting to the gym, rather than going for 30 minutes. Once I was at the gym, I would say, ‘I’m just going to get on the treadmill for five minutes.’

Eventually, he found himself reading novels for long stretches at a time while pedaling away on a stationary bike. Soon, his gym visits became daily. If he skipped one day, his mood would plummet the next.

‘It was kind of like a boost,’ he said, recalling how exercise helped him break out of his inertia. ‘It was a shift in mindset that kind of got me over the hump.’”

When you’re having trouble dragging yourself to the gym, think of the admonition of psychology writer Tal Ben-Shahar: “Not exercising is like taking depressants.” If you’ve already got the melancholic deck stacked against you, don’t ingest metaphorical despondency drugs by living a sedentary lifestyle.

Spend Time in Nature and Get Plenty of Sunshine

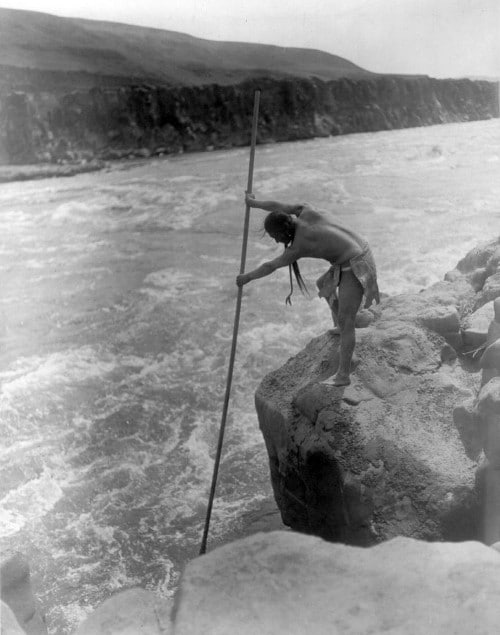

When Jack London fell into a deep depression he found his way out through exercise, the love of his wife, and plenty of outdoor activities. Horseback riding, swimming, hiking, diving, biking, sailing, and sleeping under the stars helped him recover from what he dubbed his “long sickness.” He called the city a “man trap” and argued for the necessity of getting “out of Nature that something which we all need, only the most of us don’t know it.”

If depression is partly caused by a mismatch between how our bodies and minds got used to living for thousands of years, and how we now live in the modern world, then a fundamental step in closing this gap isn’t just moving our bodies, but getting those bodies outside.

Time spent in nature centers and calms you. In a study done in Japan, researchers found that after a 20-minute walk in the forest, participants had “lower concentrations of cortisol, lower pulse rate, lower blood pressure, greater parasympathetic nerve activity, and lower sympathetic nerve activity” than those who spent time in the city instead. In layman’s terms? Walking in the woods mellows you out. In a follow-up study, time spent in nature increased feelings of vigor and decreased feelings of anger, anxiety, and depression.

It’s no wonder that mental illness is more prevalent in urban areas.

It isn’t just the peaceful, verdant surroundings of the outdoors that lift one’s spirit. Sunshine plays a depression-alleviating role as well. Its vitamin-D-producing rays not only boost mood directly, but also help raise your testosterone levels, which may in turn enhance your mood. During the dark winter months, use a 10,000 LUX light box to get the same effect. (Vitamin D supplements can be effective as well.)

You don’t have to go live in a hut in the wilderness to get the depression-alleviating benefits nature provides: do your workout outside; garden; eat your lunch in a park; take a hike; go camping when you can. The mental and physiological effects of a visit to the outdoors have been shown to last for weeks and even months.

Boost Your Testosterone

Individuals with lower levels of testosterone have been found to have an increased risk for depression. This may partly explain why women are more likely to get depressed than men and why men who undergo testosterone replacement therapy sometimes report a boost in their mood. Scientists believe that testosterone levels spur dopamine production, which in turn elevates mood.

While I significantly increased my T levels over the last several years, I can’t say I’ve really noticed a difference in my melancholy. I do feel less “tender” and am less apt to cry when sad things happen.

The mood-boosting effects of increased T may ultimately be most pronounced in those who start out with a clinical deficiency in this hormone. So file this under those things that may not help, but certainly won’t hurt — especially if you take the all-natural, side-effect-free route to increasing your testosterone. Even if boosting your T doesn’t directly make you feel any happier, it may do so indirectly by spurring positive changes in your energy and physique.

Take Some Social Medicine

If we want to live more like our buoyant, depression-free ancestors, then we would do well to try to replicate the closeness of their communities and take seriously the importance of social ties.

Anthropologists have found that individuals in hunter-gatherer tribes rarely spend time alone; their whole life and identity is intertwined with their kith and kin.

Contrast that with citizens of the modern day. A full quarter of us lack any intimate social connections at all, and many of the rest of us find our bonds meager in number and tenuous in strength. As professor of psychology Stephen Ilardi reports in The Depression Cure, this isolation leaves us without the kind of relationships that boost resistance to depression:

“The human species is hard-wired for person-to-person contact, and the supportive presence of loved ones is a powerful signal from the environment that helps keep the brain’s stress response in check. Several studies have shown that people with strong social support networks are relatively unlikely to become depressed. In fact, a British team of researchers found that simply having one supportive confidant — an emotionally close friend or family member — cut the risk of depression in half following a painful event like separation, divorce, or job loss.”

Ilardi goes on to note that even having a pet gives a person a sense of connection that curbs depression.

The flip side of the mood-boosting effect of close community is the fact that “toxic” relationships have the very opposite impact:

“Not all social contact is beneficial…Sometimes, as Sartre complained, ‘hell is other people.’ Researchers have found, for example, that the presence of a harshly critical, emotionally abusive spouse renders a person more vulnerable to depression — even more so than if they had no meaningful social connection at all.”

So prioritize the cultivation of healthy relationships, hang out less in networks and more in real communities, and cut your ties with toxic people (via negativa!).

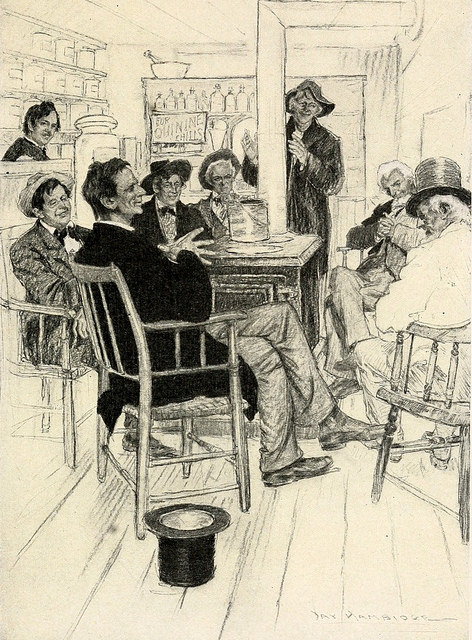

Famous melancholics like Churchill and Lincoln found time both for solitary reflection and ample socializing. That may come as a surprise concerning old Abe, as he now seems to us to be the very opposite of gregarious. But the man absolutely loved to be with friends, spinning yarns and telling jokes — such interactions were a necessary tonic in managing his melancholy.

Note to the loved ones of a depressed individual: Your friends and family members may withdraw from you when they become depressed. While a little solitude, in certain cases, and when well-directed (more on this below) can be beneficial for the depressed, they also need plenty of social interaction to keep their depression from deepening into something more serious. They won’t ask for this interaction though, and may in fact push back against it. Be persistent and stay in touch anyway. Be willing to do the heavy lifting; rather than asking the person what they want to do, plan an activity they’ll enjoy, and tell them you’ll swing by to pick them up. All they’ve got to do is shuffle out the door.

Eat Right

Research suggests that what you eat can be connected with depression. Individuals who have a poor diet — high in fried foods, refined carbohydrates, and processed meats — reported more depressive symptoms compared to individuals who maintain a healthier and more balanced diet. But you probably don’t need studies to tell you something you’ve surely noticed yourself: when you eat like crap, you feel like crap.

So ingest the kind of stuff that matches how you want to feel: more natural, whole foods like eggs, meat, veggies and fruits, and less refined and overly processed junk food.

You may also consider intermittent fasting. Research shows that intermittent fasting can help increase mood and alleviate depressive symptoms. In addition to this direct effect, it also increases your willpower and discipline, which can help you take a stronger and more stable stance when grappling with your black dog.

Stay tuned for an in-depth article on intermittent fasting in the next few months.

Experiment With Supplements

Even when you’re generally eating healthier, most of us still aren’t perfect and have a hard time getting all the nutrients our bodies need to perform optimally from food alone. This is especially true for things like fatty acids that may play an important role in regulating mood. Supplements can fill the gap — so experiment to see if they make a difference for you. (If you’re already taking an antidepressant, be sure to talk to your doctor first, as the mix of drugs and supplements can create negative interactions).

Below I’ve outlined a few of the most promising:

Fish oil. Research has shown that regular use of fish oil supplements or other sources of Omega-3 fatty acids may help alleviate depression just as well or even better than antidepressants, but without the negative side effects.

Researchers believe that omega-3 fats assist in neurotransmitter transmission — particularly with dopamine and serotonin — as well as reduce inflammation in the brain.

There are two types of molecules that make up omega-3s: DHA and EPA. Depressed individuals usually lack both, but research suggests that EPA is the most potent when it comes to reducing a depressed mood. Studies have found that 1000-2000 milligrams of EPA a day has the best anti-depressive effect. Dr. Ilardi recommends starting with a fish oil supplement that provides 1000 mg of EPA and 500 mg of DHA each day. It’s hard to find fish oil supplements that provide that exact ratio. The one I take is Ultra Strength Rx Omega Factor. One soft gel packs 645 mg of EPA and 250mg of DHA, so I take two in the morning to get a total of 1290 mg of EPA and 500 mg of DHA.

One thing to keep in mind with omega-3 supplementation is that it usually takes a few weeks before you’ll notice any improvement; so don’t give it up if you don’t feel any different right away. If you still don’t notice any improvement after a month, you might consider upping your dose so that you’re getting around 2000 mg of EPA a day.

Prebiotics and probiotics. During the past few years, researchers have discovered that the billions of microbes swimming in our gut and living on our skin have a profound impact on various aspects of our health, including our mood. Research has shown that changes in gut bacteria can reduce anxiety in mice, and similar results are being seen in humans. In a study out of England, a group of healthy people were randomly given a prebiotic (carbohydrates that serve as food for your preexistent gut bacteria) or a placebo. The individuals who took the prebiotic paid less attention to negative information and had lower cortisol levels than those who received the placebo. A 2011 study in France found that participants who took a probiotic (strains of good bacteria) for 30 days also had reduced levels of psychological distress.

It should be noted that the connection between gut bacteria and mental health is still inconclusive. Other studies have cast doubt on the effectiveness of pre- or probiotics as a way to alleviate depression. But it can’t hurt to give it a try. To up the amount of good bacteria swimming in your gut, take a prebiotic and probiotic supplement and/or eat more fermented foods like yogurt, sauerkraut, or kombucha.

My calmness stack. For the past few years I’ve been taking a nootropic stack that’s supposed to help with stress. I picked it up from The Chemistry of Calm by Dr. Henry Emmons. I’ve had good success with it, and Kate definitely notices when I’ve forgotten to take my supplements!

- Omega-3 — Start off with a supplement that provides at least 1,000 mg of EPA and 500 mg of DHA.

- Vitamin D3 — Start off with 2,000 IU a day. I do 5,000 IU a day.

- Rhodiola rosea — 250 mg twice daily. May help improve serotonin and dopamine levels and counteract the effects of cortisol.

- 5-HTP — 50-100 mg twice daily. Boosts serotonin.

- NAC — 600 mg up to two times daily. Research has shown that it can reduce anxiety by modulating glutamate and dopamine levels in the brain.

Those are the supplements I have found to be the most effective in my personal experiments. But there are others Dr. Emmons recommends in The Chemistry of Calm, including taurine and L-theanine. As with all this advice, you just have to experiment and see what works for you!

Should I Take an Antidepressant?

Ever since the 1980s, antidepressants have become the standard first-line of treatment for individuals complaining about depression. Patients can even get a prescription without visiting a psychiatrist or therapist — an appointment with the family doctor will do. Today, nearly 40 million Americans take some type of antidepressant, making it the most prescribed pharmaceutical in the United States.

The idea behind antidepressants is that depression can largely be traced to a chemical imbalance in the brain and that medication can restore this balance.

You’d think that with the growing number of Americans getting prescribed antidepressants, there would be plenty of research that shows they work as described and that they’re an effective form of treatment for depression.

You’d think that, but you’d be wrong.

The theory behind selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — the most common type of antidepressant — is that folks suffering from depression have an inadequate amount of the neurotransmitter serotonin. SSRIs remedy this by blocking the reabsorption of serotonin in the brain, leaving more of the neurotransmitter between the synapses of neurons, which in turn is supposed to lift mood. Yet recent research has shown that serotonin might not actually play that big of a role in causing depression, and that, if anything, it may be that depression sufferers have too much serotonin, rather than too little.

This may explain why during the FDA trials for SSRIs back in the 80s and early 90s, they were shown to be only a little better than a placebo in alleviating depression. More precisely, about 40% of trial patients got better by taking a sugar pill, while 50-60% improved by taking an antidepressant.

In 2006, the National Health Institute sponsored a study called STAR*D to evaluate the effectiveness of various depression treatments. Out of 4,000 patients, a little less than 30% experienced remission of depression after taking an SSRI for 14 weeks. During follow-up, many of the patients who did recover after taking an antidepressant relapsed. Several other meta-analyses of studies done on antidepressants have shown similar results — that they perform about as well as a placebo. Drug companies have even developed drugs that are supposed to boost the efficacy of the drug you’re already taking, if the drug you’re already taking hasn’t been effective.

In addition to the research showing that SSRIs might not work much better than chance, several studies have shown that they cause adverse side effects like weight gain and loss of sexual and even romantic interest in one’s partner (that’s what too much serotonin in the brain can do to you). SSRIs may also blunt a person’s ability to read facial expressions in others. The problem here, of course, is that lack of interest in and problems communicating with one’s partner can cause relationship problems, and relationship problems can push you deeper into depression.

The even more disturbing side effect of SSRIs is the way they increase suicidal thoughts and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults up to about age 25. Research as to whether these drugs increase suicidal thoughts and behavior in older adults is unclear. Because of these negative side effects, many individuals quit taking antidepressants earlier than their doctor recommended.

Given all of the above, it would be easy to write off antidepressants altogether. But that would ultimately be short-sighted.

While the combined research suggests that antidepressants — particularly SSRIs — aren’t very effective in treating depression in most people, the research does suggest that antidepressants work much better than placebos in individuals who are severely depressed (as in they can’t get out of bed and take care of basic life functions). For these individuals, antidepressants can be a godsend; they lift the intense, gray fog long enough to start taking small steps to get their life back on track. And as we’ve discussed, these small steps then often lead to a positive cycle of behaviors that eventually pulls the person out of their dark place.

So, should you take an antidepressant?

Well, it depends. And it’s a conversation you should have with a trained psychiatrist.

The research suggests if you’re feeling mildly depressed, you’d be just as well off taking a placebo. Given the number of possibly negative side effects that accompany antidepressant use, instead of making medication your first line of treatment, try some of the research-backed suggestions outlined in this article. If you still haven’t been able to shake the low mood after a few months of consistent effort, then talk to your doctor about getting on medication.

If you’re severely depressed then definitely consider asking your doctor about taking an antidepressant. Just don’t expect a miracle with it. You may not experience any effects on your mood, and if you do, such effects will likely take at least to 2-4 weeks to become noticeable.

Most importantly, don’t think of your daily pill as a silver bullet for your depression; drugs mark the beginning, rather than the end of depression management. Think of an antidepressant as something that will enable you to get started with making larger lifestyle changes — the push that will set a long line of dominos in motion.

Get More Sleep (But Not Too Much)

Sleep significantly affects our overall physical and mental health, including our mood. If you don’t get enough or if you get way too much, it can heighten your stress and depress your spirits. And the lower and lower your mood gets, the harder and harder it becomes to fall and stay asleep; insomnia is a common side effect of depression. Sleep deprivation and depression can thus turn into a vicious cycle.

But you can take action to help yourself get some better shut-eye, which can reverse the direction of that feedback loop. Just don’t get more than about 10 hours a night (on average, for normal adults); like too little sleep, too much sleep can deepen your depression.

Meditate

There’s a growing amount of research showing that mindfulness meditation practiced consistently can be as effective as antidepressants in treating depression, but without medication’s negative side effects. Researchers believe meditation helps keep depression at bay both by reducing activity in the amygdala — the part of your brain that governs the stress response — and reducing activity in our brain’s default mode network — an area of the brain that’s linked to feelings of unhappiness.

As we’ll mention below, there’s a whole form of therapy based on meditation called Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) that you might be interested in checking out. But mindfulness meditation is something you can start doing right now on your own. It requires very little time — 10 minutes a day will do the trick. A great (and free!) online app to check out is calm.com. It provides guided meditations that last 2, 5, 10, 15, or 20 minutes. You’ve got 10 minutes a day. No excuses.

Learn to Soak in the Positive

Melancholic individuals tend to be pessimistic about most things in life. And as we’ve discussed previously, viewing life through the lens of “depressive realism” can be a source of wisdom and insight. But there comes a point when pessimism becomes irrational and counter-productive and just pushes you deeper and deeper into a funk.

People who are prone to depression often have minds that are like Velcro for negative things and Teflon for positive things; that is, they notice everything negative about their lives, while positive things just slip past them. This effect is likely only enhanced by our modern environment and a non-stop news cycle that blares disaster-filled, anxiety-ridden, fear-mongering stories at us 24/7. After perusing the comment section of YouTube, you could be forgiven for believing human civilization will come to an end by 2020.

One thing that has helped me counteract this Velcro/Teflon effect and get a handle on my hyper-Eyoreness (besides limiting my news and social media consumption!) is practicing the suggestions made by neuropsychologist Dr. Rick Hanson in his book Hardwiring Happiness. Whenever you have a positive experience, take 5-10 seconds to really relish it. Enrich the feeling. Let it fully sink into your mind. The positive experiences don’t have to be big — it could be a beautiful sunset, getting a great hug from your kid, or taking the first bite of some magnificent BBQ ribs.

The goal with this exercise is to “hardwire” your brain to focus more on the positive and less on the negative — to reverse the respective positions of your Velcro and Teflon. I’ve been doing it off and on for the past year, and have noticed that I’m much less peevish when I’m consistently making it a habit.

Should I Visit a Therapist?

One of the most prominent and popular ways of dealing with depression is undergoing therapy with a psychiatrist or psychologist. Should you take that path? Let’s first give a brief rundown on the options that are out there:

Freudian Psychodynamic Therapy

- Form: Seeking to uncover the source of your depression by exploring your emotions and experiences.

- Effectiveness: 30% to 40% of individuals who undergo psychodynamic therapy will see a reduction in depressive symptoms.

- Possible Pros: Research suggests results may be longer lasting than other forms of therapy.

- Possible Cons: Seeing results can take a longer time commitment than other forms of therapy — several months to a year or more.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Form: Identifying and transforming faulty cognitive patterns that may be leading to depression.

- Effectiveness: 30% to 40% of patients will see a reduction in depressive symptoms by the end of a 12-week treatment cycle. Individuals who combine CBT with medication see a higher remission rate and have less chance of relapse.

- Possible Pros: More practical and shorter in duration; CBT doesn’t focus on analyzing past emotions or past experiences, and lasts for 4-12 weeks.

- Possible Cons: Research shows that preventing relapse after an initial CBT treatment cycle may require periodic follow-ups to “tune-up” your thinking skills.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy.

- Form: Teaches mindfulness meditation and how to step back from negative thoughts in order to neutrally observe them.

- Effectiveness: Just as effective as CBT, but less effective in individuals who have had only one or two major depressive episodes.

- Possible Pros: Cultivates practices and a mindset that may be just as beneficial during non-depressed periods. Can be effective for severe cases.

- Possible Cons: n/a

As you can see, each type of therapy is about equally effective, and research suggests that the type you choose to use doesn’t ultimately really matter — just talking to a helping and understanding person on a regular basis is what does the trick. Which type of therapy you decide to do will end up being a matter of preference.

If you do decide to begin therapy, do some homework first. See if you can set up an initial appointment to ask some questions. Inquire about the therapist’s background and training, as well as their experience specifically treating depressed patients. Ask about their approach — CBT? Psychodynamic? — as well as their philosophy on medication. You’ll also want to know if they take insurance. Many therapists don’t, and that could make treatment unaffordable for you. (If that’s the case, ask about setting up a payment plan. For lower cost options, look into community health centers or psychologist training clinics at local colleges. If you’re a student yourself, schools often offer free counseling.)

Your primary goal during this initial visit is to see if the doctor seems trustworthy, and just as importantly, if you feel comfortable talking to them. That fact alone can go a long way in your success with therapy.

So, how/when do you know if therapy is the right choice for you? There are no clear-cut answers, but there are a few things to consider. First, as we’ve seen, all types of therapy are about as effective as antidepressants alone, but, the “side effects” of each kind of treatment are different. Therapy may help you dig into the fundamental origin of your depression and is free of negative neurological/biological effects. But it will cost you time and money. Antidepressants, on the other hand, are very convenient, but may have deleterious effects on your body and mind, and work by treating depression’s symptoms rather than addressing its potentially deeper roots.

So weigh both sides of the coin.

My advice (and remember, I’m not a doctor) would be to try the suggestions in this article first, and if you don’t find success with them, then decide, based on your personal circumstances, whether therapy or antidepressants would be your best next move. If you think the roots of your depression run deep and are lodged in your upbringing or negative thought patterns, therapy may be the way to go; if you think your depression is more passing and random, then antidepressants might be the route for you. If neither work, then you may ultimately need both!

Depression Management Prong #2: Find Ways to Make Depression as Constructive and Generative as Possible

It was Churchill who most famously referred to his depression as the “black dog.” While he only fell into one major episode of it, he experienced bouts of melancholy throughout his life. He mitigated its effects through a myriad of hobbies and interests. And instead of being a detriment to his goals, he ultimately channeled his melancholy towards accomplishing a greater purpose.

According to the evolutionary theory of depression, a bout of melancholy was designed to alert the individual to the fact they were potentially on the wrong path or that there were threats in the environment that needed to be addressed. It spurred the sufferer to withdraw and take a time out in which he or she could analyze the situation, ferret out and troubleshoot the issue, and reemerge in a better place than before.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to take a real time-out in our modern world; gaps in one’s resume are frowned upon; stepping away from some of your responsibilities is read by others as laziness. Within this reality, though, you can carve out some space to utilize depression as it was intended — to help you understand more about the world, yourself, and how you can become a better man. Here’s how.

Reduce Your Stress

Contrary to the popular association of depression with laziness, it can actually arise from trying to do too much. Both of my bouts of depression were precipitated by a period of grinding work and an overly packed schedule.

As we’ve been discussing, activity itself is not the problem, and is in fact a central part of the solution. But there’s a difference between taking care of necessary maintenance tasks, and being overwhelmed by plain old “busy work” — responsibilities that have nothing to do with what’s important in your life, cry out with a false sense of urgency, and make you sick rather than well.

Chronic stress does a number of things to your body and mind that make you vulnerable to depression, and this sets up another of the illness’s catch-22s: you get depressed because you’re stressed, and you can’t alleviate it because you don’t have time to even think about what’s gone wrong.

Thus stress reduction could readily fit on either of depression management’s prongs. It strengthens your resistance to the ill effects of the black dog, and, should it arrive anyway, it also opens up time and space in which to reflect on how to deal with it.

The two biggest things that have helped me manage my stress and balance my life are 1) saying “no” to avoid over-committing myself, and 2) planning my week and days out consistently. As soon as I stop doing those things, I start getting pretty peevish, pretty fast. I have to make sure to maintain some breathing room in my schedule for my mind and body to recuperate.

The more serious your depression, the more you may need to lighten your load to create the time and space to do the important introspective work your depression is prompting you to take care of. While slowing down may make you uncomfortable, realize that it’s only temporary. If you allow your “time-out” period to strengthen you, you’ll be able to emerge from your funk ready to take on heavier loads of purpose-filled pursuits. It’s preparation for the next phase of your life; if you try to barrel through it, the result may actually permanently cripple you, so that you never reach those future goals. In other words, by taking a short time-out now, and figuring yourself out, you’ll be able to do much more later than had you skipped this phase, burned out, and spiraled into a lower path for your life.

Focus and Curtail Your Tendency to Ruminate

Depression tends to turn your thoughts compulsively inward. This kind of solitary rumination can be beneficial, if you keep it short and focus more on what might be at the root of your melancholy rather than on your feelings themselves. Depression-driven introspection and analysis can help you break down problems and figure out solutions.

But, it’s a process that you have to actively manage, because it has a point of diminishing returns past which it becomes detrimental.

What’s seductive, and potentially destructive, about rumination is the feeling you frequently get in the midst of it that if you just brood a little while longer, you’ll suddenly have an epiphany that explains everything. But if you haven’t gotten an insight after about 10 minutes, you’re probably not going to. To continue to ruminate will likely leave you more depressed than before, for reasons Dr. Ilardi explains:

“The brain uses our mood state as its single most important memory cue. Believe it or not, the brain tags every one of our memories according to the emotional state we’re in when the event occurs. And whenever we’re in that same mood down the road, this can serve as a powerful retrieval cue.

When you’re sad, for example, that despondent mood starts lighting up all sorts of memories from other moments when you were in similarly low spirits: previous experiences of failure and loneliness and rejection and similar unhappiness.”

In other words, once you start ruminating about how bad you feel and the things you think are wrong with you, your brain starts bringing up past times you brooded over your melancholy and your perceived deficiencies. Which of course just makes you feel even worse. So you figure you’ll ruminate some more to figure out why you’re now feeling really bad. And the cycle continues.

Breaking this cycle of despondency means distracting yourself from your thoughts and engaging in an activity that will give the brain something else to chew on. If you can’t seem to will yourself to break away, allow yourself to be responsive to the promptings of another, when they suggest doing or talking about something else.

Note to the loved ones of a depressed individual: It may seem like you’re helping and being compassionate by asking your friend to talk about exactly how they’re feeling. A little of this may be helpful, but it’s more likely to just make them feel worse. Instead, distract them; invite them out to a movie or to go fishing, and talk about other stuff to get their mind off their melancholy.

Engage in “Bibliotherapy”

One of the best ways to focus your introspective thoughts during a bout of depression is to engage in bibliotherapy — reading books about melancholy. Such study will help you understand more about yourself and what you are experiencing.

I’m constantly reading and re-reading books about managing depression and becoming more resilient. I have found this practice enormously beneficial in learning how to accept, manage, and make the most of my melancholy. And I need the regular reminder to “hold fast” to the best practices I have already implemented and can’t afford to let slip.

Below is a list of the books that I’ve found the most useful:

- Rewire Your Brain by John Arden

- The Depression Cure by Stephen Ilardi

- Feeling Good by David Burns

- Undoing Depression by Richard O’Connor

- The Depths by Jonathan Rottenberg

- Resilience by Eric Greitens

- Learned Optimism by Martin Seligman

- On Depression by Nassir Ghaemi

- Hardwiring Happiness Rick Hanson

- The Chemistry of Calm by Henry Emmons

- Change Your Brain, Change Your Life by Daniel Amen

- Man’s Search For Meaning by Victor Frankl

- Rethinking Depression by Eric Maisel

- Lincoln’s Melancholy by Joshua Wolf Shenk

Besides those books, I think there’s something to be said for reading “melancholy” literature. It puts your depression into some much-needed perspective. Here are a few favorites of mine:

- The Psalms

- Book of Job

- The Road by Cormac McCarthy (anything by McCarthy, really)

Writing “Psychoanalysis” (AKA Journaling)

If depression may be a natural signal from your mind that you need to analyze and address some underlying issues or problems in your life, then journaling is an excellent way to structure these sessions.

Research has shown that using expressive writing can help reduce unhealthy rumination and, as a consequence, feelings of depression. According to Dr. Michael Frank, a co-director of the International Traumatology Institute at the University of South Florida in Tampa, “journaling provides a way of turning subjective thoughts to objective words on paper that can be analyzed, changed, even destroyed.” The act of writing — a highly analytical activity — forces you to be more rational about your negative emotions; it makes you step outside of yourself and thus puts things into perspective.

Dr. James Pennebaker, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, is the leader on research into the idea of writing-as-therapy. He suggests that you set aside 20 minutes a day and write non-stop. What about? Pennebaker suggests the following:

- Something that you are thinking or worrying about too much

- Something that you are dreaming about

- Something that you feel is affecting your life in an unhealthy way

- Something that you have been avoiding for days, weeks, or years

Don’t worry about punctuation, spelling, or organization. It’s a free writing exercise. Some research has shown that individuals who do this exercise start seeing improvements in mood, blood pressure, and immunity within 3-4 days.

I know that when I consistently journal and do these writing exercises, my mood is significantly better, and I’m less peevish. And when I do get in a funk, this habit helps me get out of it.

Have a Purpose Outside of Yourself

“It can be seen that mental health is based on a certain degree of tension, the tension between what one has already achieved and what one still ought to accomplish, or the gap between what one is and what one ought to become. Such a tension is inherent in the human being and therefore is indispensable to mental well-being. We should not, then, be hesitant about challenging man with a potential meaning for him to fulfill….I consider it a dangerous misconception of mental hygiene to assume what man needs in the first place is equilibrium…a tensionless state. What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a freely chosen task. What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him…And one should not think that this holds true only for normal conditions; in neurotic individuals, it is even more valid. If architects want to strengthen a decrepit arch, they increase the load which is laid upon it, for thereby the parts are joined more firmly together.” –Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

One of the gifts of depression is its tendency to give you a single-minded focus. But this promise contains both a paradox and a peril.

As we’ve discussed throughout this section, sessions of solitary, proactively-directed inward introspection can be just what the doctor ordered in helping you utilize depression as it was intended — to analyze, address, and troubleshoot issues in your life and become stronger for it.

But, one’s focus must not remain inwardly-directed indefinitely.

Just like the process of rumination itself, it reaches a point of diminishing returns.

So you’ve developed greater strength and self-understanding…for what purpose?

If it’s just an effort to make yourself feel better, happiness — in the form of flourishing — will elude you.

Our culture as a whole emphasizes the self as the highest good. Everything is all about you. “What will make me happy?” “How can I get people to like me?” “What’s in it for me?”

But when we only have our own feelings and goals on which to concentrate, their importance and intensity are amplified to an unhealthy degree. As Dr. Martin Seligman puts it, believing you “are the center of the world…makes individual failure almost inconsolable.”

Seligman argues that modern individualism has a lot to do with why depression rates have increased so precipitously over the last fifty years. Unlike citizens of the 21st century, our forebearers had a lattice-work of external interests, relationships, and animating purposes:

“Individual failure used to be buffered by…the large ‘we.’ When our grandparents failed, they had comfortable spiritual furniture to rest in. They had, for the most part, their relationship to God, their relationship to a nation they loved, their relationship to a community and a large extended family. Faith in God, community, nation, and the large extended family have all eroded in the last forty years, and the spiritual furniture that we used to sit in has become threadbare.”

While it’s fine to work on ways to improve your own life, occasionally forgetting yourself and looking for ways to serve others and the greater good, can paradoxically be the surest way to become truly happy. The more you turn your focus outward and the more involved you become in causes outside yourself, the better you’ll feel.

At the end of the day, the greatest antidote to depression is having a greater purpose — a reason to get out of bed when you don’t feel like it, a reason to get better and become stronger, a reason to live. Men who have not only suffered from depression, but used it to drive their life’s work, understood this.

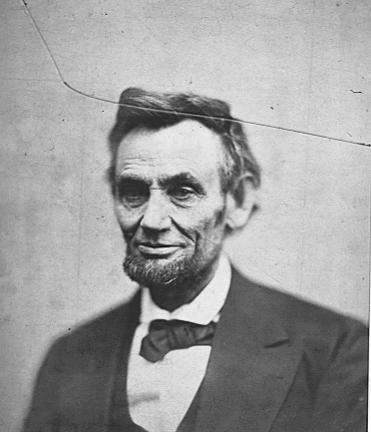

Case in point: Abraham Lincoln. He would suffer from periods of deep gloom throughout his entire life and from a chronic melancholy even in his “good” times. His depression was so profound you could see it engraved on his face and even manifest in his gait; as his law partner observed, “Lincoln’s melancholy dripped from him as he walked.”

At age 32 and in the trough of a major depressive episode, the future president despaired that he would never get better. He wrote to his partner to say:

“I am now the most miserable man living. If what I felt were distributed to the whole human family there would be not be one happy face on the earth. I must die or be better it appears to me.”

As Joshua Wolf Shenk recounts in Lincoln’s Melancholy, at first the despondent lawyer wanted to observe depression from the very belly of the beast and intentionally allowed himself to be overcome by his mental agony; “he let himself sink to the bottom and feel the scrape.” There Lincoln might have remained, but rather than letting depression crush him, he decided to harness it — to let his personal suffering move him with compassion to alleviate the sufferings of others: During “his time of hurt,” Shenk writes, Lincoln looked:

“not to lighten his load so much as to increase it. Having flirted with a desire to die, he asked himself what he needed to live for, and he found an answer that would stay with him throughout his adult life. In the nadir of his friend’s depression, [Joshua] Speed told Lincoln that he would die unless he rallied. Lincoln said that he could kill himself, that he was not afraid to die. Yet, he said, he had an ‘irrepressible desire’ to accomplish something while he lived. He wanted to connect his name with the great events of his generation, and ‘so impress himself upon them as to link his name with something that would redound to the interest of his fellow man.’ This was no mere wish, Lincoln said, but what he ‘desired to live for.’”

Once Lincoln had decided “whether he could live, he turned to how he would live.” Turning to the world around him, he built “bridges out from his lonely self, he engaged with the psychological culture of his time, trying to make himself emotionally and mentally, investigating who he was, what he could do to change, and what he could only accept and endure.”

After taking the time to create a mental scaffolding built from a deep understanding of his own identity, the nature of his depression, and how he could best deal with his black dog, Lincoln was ready to begin his life’s work. His path to the presidency was long and sometimes wholly demoralizing. But a sense of duty and destiny kept him pushing along. Shenk’s observation of Lincoln’s path provides an unmatchable summary of everything we’ve talked about here in this article, and the three stages a man must go through to turn depression from a merely crippling disease to a generative rite of passage:

“In mythical stories, a character undertakes a journey, receiving at every step totems that, at the time, have no clear value but at the end turn out to provide the essential tools for a final struggle. We can see this in Lincoln’s journey. In the first stage, he asked the big questions. Why am I here? What is the point? Without the sense of essential purpose he learned by asking these questions, he may not have had the bedrock vision that governed his great work. In the second stage, he developed diligence and discipline, working for the sake of work, learning how to survive and engage. Without the discipline of his middle years, he would not have had the fortitude to endure the disappointments that his great work entailed. In the third stage, he was not just working but doing the work he felt made to do, not only surviving but living for a vital purpose. Yet he constantly faced the same essential challenges that had been presented to him throughout…But he repeatedly returned to a sense of purpose; from this purpose he put his head down to work at the mundane tasks of his job; and with his head down, he glanced up, often enough, at the chance to effect something meaningful and lasting….

The overarching lesson of Lincoln’s life is one of wholeness. Knowing that confidence, clarity, and joy are possible in life, it is easy to be impatient with fear, doubt and sadness…[Yet] The hope is not that suffering will go way, for with Lincoln it did not ever go away. The hope is that suffering plainly acknowledged and endured can fit us for the surprising challenges that await.”

It’s worth reiterating this conclusion as Shenk does elsewhere in his book:

“This is not a story of transformation but one of integration. Lincoln didn’t do a great work because he solved the problem of his melancholy. The problem of his melancholy was all the more fuel for his great work.”

A man who lives only for self will find it easy to retreat to the point of rarely emerging from the covers of his bed. A man with a purpose outside of himself, with a sense of duty, will have an easier time summoning the motivation to keep moving. As Eric Greitens argues, every man must know the answer to this question: “What’s your challenge?”

Conclusion

“In the midst of suffering resoluteness of soul will be as good as a cure, for the soul renders lighter any burden that it endures with stubborn defiance. Remember that pain has this most excellent quality: if prolonged it cannot be severe, and if severe it cannot be prolonged; and that we should bravely accept whatever commands the inevitable laws of the universe lay upon us.” –Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius.

It’s amazing how many articles we’ve done over the years tackling a wide variety of problems where the solution comes down to: exercise, eat right, get outside, have a purpose.

I suppose it shouldn’t be surprising though; despite all the sexy new cures and hacks and groundbreaking scientific studies that come out, tried and true advice that’s been around for thousands of years continues to form the crux of how to live the good life.

But just because an answer is simple, doesn’t mean it’s easy. I don’t want to arrive at the end of this and give you a smile and a back slap, and have us part ways with my saying, “Isn’t it great that because you’ve got an intractably melancholic temperament you get to see the world realistically and you’re extra incentivized to be intentional and rigorous about practicing healthy habits? What a great stroke of luck!”

Depression may have an upside, but that doesn’t mean you’ll always appreciate it. I still have times where I feel incredibly frustrated that I have to work so damn hard to attain a degree of good mood that other people just wake up to each morning. Having to put forth effort every single day sometimes makes me want to throw myself a pity party.

But the more I’ve researched depression, and the more I’ve come to accept its true nature and modified my expectations for “recovery” in line with it, the more I’ve come to peace with my melancholic temperament. Everybody’s born with mental and physical traits that make their lives more or less challenging. In many other ways, I’ve been incredibly blessed. So I accept my challenge and I am determined to lighten the burden of my depression in whatever ways I can (which also lightens its burden on my family), and to carry with dignity what cannot be discarded for the rest of my days.

I hope those of you who struggle with depression personally, or who have a friend or family member who does, have found this series useful and edifying. One of the definitions of depression that’s been around the longest is “Fear and sadness without cause.” I hope I’ve shown that sometimes there is a cause, that it isn’t always bad, and that you don’t have to be afraid when you see the black dog show up at your door. When it does, know that you don’t need to kill it, and that he need not kill you. You can put that pooch on a leash and walk together side-by-side through this life’s journey.

Read the Entire Series

My Struggle With Depression

The History of Depression

What Causes Depression?

The Symptoms of Male Depression