I’ve noticed something you’ve probably noticed too.

Grown men dressing like boys.

In a typical American restaurant, you’ll find 30- and 40-something men dressed like their pre-teen or teenage sons: Air Jordans, a graphic tee, and an oversized flat-brimmed ballcap.

The puerility of men’s clothing is on full display at an American airport. You’ll see men my age shuffle toward TSA in elastic-waist joggers, video game t-shirts, and Crocs. Their kids are wearing nearly identical outfits.

I make the Clint Eastwood Gran Torino grimace at the sight.

Before you peg me as a middle-aged curmudgeon, my 14-year-old son notices the sad state of American grown-man style too: “Hey, Dad,” he’ll say, “that guy over there dresses like I did in 6th grade. He does not mean business.”

Are we just uptight squares who can’t let people enjoy themselves?

Maybe.

But I also think there’s a visceral recognition in both of us that your exterior appearance often reflects the state of your interior character. When a man dresses like a boy on the outside, there’s a chance there’s some stunted development on the inside.

Until very recently, cultures across the world — from sophisticated civilizations to remote tribes — connected a man’s dress to his development into maturity, sometimes even making a wardrobe change a rite of passage into manhood.

In ancient Rome, for example, where the toga was the common form of dress, there was a difference between a boy’s toga and a man’s toga.

At around 16, Roman boys swapped their purple-trimmed toga praetexta for the plain white toga virilis in a public rite of passage that marked their entry into manhood. The father led the boy to the Forum to register as a citizen and make sacrifices. Back at home, the boy dedicated his toys and protective amulet to the household gods. He was now a man.

Past cultures understood something we’ve forgotten: that how a man dresses shapes how he sees himself, how he acts, and how others treat him, and these dynamics in turn influence the culture at large.

So let’s take a look at the history of the distinction between boyswear and menswear, why it vanished, and why it’s worth reviving.

What Happened to the Tradition of Men Dressing Differently From Boys?

Across the last two centuries of Western male dress, boys’ clothing tended to be looser, brighter, and more utilitarian — made for getting dirty and handling rough-and-tumble play. Men’s attire, by contrast, was more tailored, sober, and symbolic of dignity and responsibility.

From the 1800s through the 1940s in the West, boys typically wore short pants with knee socks, paired with buttoned jackets or tunics in the late 19th century, and with blazers or pullover sweaters in the early 20th. White-collar men, on the other hand, wore full, formal suits. Short pants signaled boyhood; full-length trousers signaled manhood. When boys got their first long trousers — or received a watch or tie as a gift — these were signals that the young lad was joining the ranks of the men.

Headwear also marked the age divide during these eras: in the 19th century, boys wore flat caps, while adult men wore top hats or bowlers; by the early 20th century, men had shifted to fedoras, trilbies, or homburgs.

By the 1950s, boys began wearing jeans, t-shirts, baseball jackets, and Chuck Taylors for play, while still dressing in nicer trousers and button-down shirts for school. Adult men might throw on a GI-issue undershirt for chores around the house, but they didn’t wear t-shirts in public. During their leisure time, they opted for sport shirts, chinos, and cardigans, which were casual but still distinctly grown-up in cut, fabric, and styling.

The distinction between boyswear and menswear began to erode in the 1960s. The counterculture rejected the older generation’s values, including their fashion mores. Youth culture became the ideal. “Don’t trust anyone over thirty,” they said. And the subtext wasn’t subtle: “Don’t act like anyone over thirty. And definitely don’t dress like them. What are you? Your old man, man?”

Sociologists see this moment as the start of a broader shift in American culture. The idea that age brings dignity felt outdated. It became less desirable to seem respectable than cool, and grown men began to dress more like those who represented the locus of cool — the young.

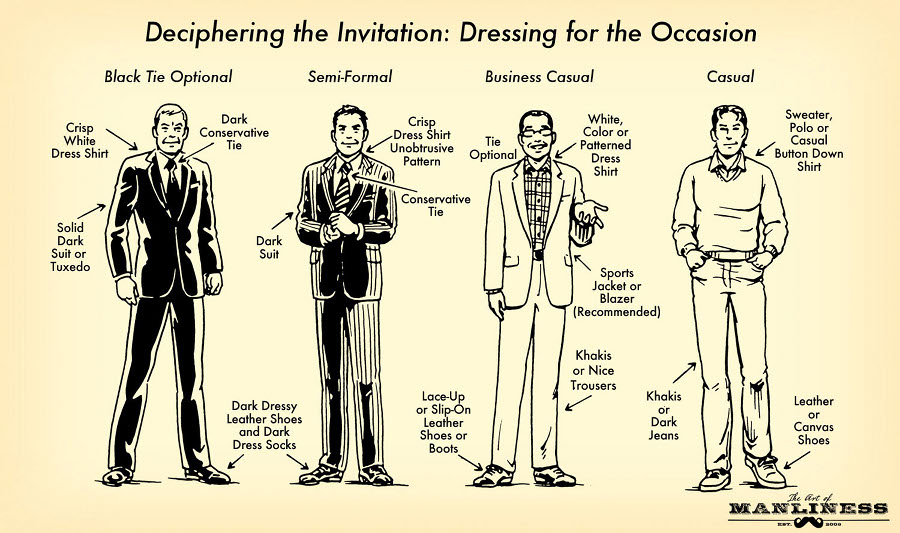

Accelerating this shift was the growing casualness of culture overall. Dress codes loosened in workplaces and schools, and the expectation that you would, say, wear a button-down shirt and tie to a baseball game fell to the wayside. And it’s a lot easier to build generation-signaling style distinctions into more structured clothing than it is leisurewear; a t-shirt is a t-shirt.

Nonetheless, up through the 90s, boys and men still looked at least a little different — even when they wore similar things. There were Dad jeans and boy jeans. Dad sneakers and boy sneakers. Dad was more likely to be in a polo, his son in a tee.

But even those subtle distinctions faded in the 2000s. A lot of why men had continued to look different from boys is that they had to dress up and wear a different kind of clothing to work. But now offices further loosened their dress codes, and hoodie-clad Silicon Valley entrepreneurs became the new models to emulate. Then, when remote work exploded during the pandemic, men had even fewer reasons to even own anything but the most casual clothes — the kind least distinguishable from what young people already wore.

Add in the rise of athleisure — clothing least suited to signaling any age-based distinctions — and the result is this: boys and men alike now spend most of their time in joggers, sneakers, and t-shirts and look very much the same.

The Cultural Cost of the Flattened Age of Dressing

While changing style mores might be chalked up as a neutral, inevitable cultural evolution, there is a cost both to individuals and society as a whole when the sartorial line between boys and men is erased:

Men take themselves less seriously. Even when a culture’s formal rites of passage didn’t involve a wardrobe change, simply beginning to wear grownup clothes helped young men psychologically transition into manhood. Wearing clothes associated with being a mature man helped shift their mindset into the role they were stepping into.

A large body of research has shown that clothing impacts not just performance but also self-esteem, confidence, and mood. People wearing formal or “professional” attire report feeling more competent and authoritative. Those in casual or athletic wear tend to describe themselves as less assertive.

If people worry that men don’t seem very mature anymore — that men don’t act like men — at least part of the reason may be that they no longer dress like men. When men spend most of their time in sweatpants and t-shirts, in clothes that are indistinguishable from what their children wear, they may take themselves a little less seriously, have less of a sense that they really have arrived firmly in adulthood and need to find the solid traction attendant to that stage, and have less confidence in what they’re capable of.

When men are wearing the same clothes at 35 that they wore at 15, it may add to a feeling of being in developmental limbo and of all the life stages running together.

People take men less seriously. Research also shows that how you dress influences how other people perceive you. For example, job interview studies show that applicants in adult-coded attire — dress shirt, well-fitted trousers — score higher on perceived competence than equally qualified peers in casual gear. Teaching assistants earn more authority points with students when wearing a tie. When you look like the grown man in the room, people treat you like a grown man.

It’s hard to take a 40-year-old guy in Nike hi-tops and a flat-billed ball cap very seriously, and when men dress like boys, they may diminish their influence.

As a WFH dad who dresses most days in jogger pants and a t-shirt, I do wonder sometimes if my getup diminishes my sense of authority with my kids and the level of respect they have for me. Certainly, for better and worse, they bring a much greater level of casual familiarity to our interactions than I ever did with my parents, and how I dress is likely one reason for that.

Culture loses its grown-ups. If the erasure of the line between boyswear and menswear makes men feel less secure in their status as adults and diminishes their influence, that not only affects them as individuals but impacts the culture as well. Sociologists note that rites of passage serve both the initiate and the tribe; the individual receives clarity about identity: I was X; now I am Y. The tribe gains reliability — We know what to expect from Y. When rites disappear, both parties drift.

In a society where men never stop dressing like they did in high school, they may lack the confidence to step into leadership roles. And when men don’t look like leaders, it further erodes public trust in the institutions they’re supposed to represent.

Young people also miss out on the comfort and ballast that comes with entering the orbit of a man who seems grounded and mature — someone who signals, even without saying much, that adulthood is a real, distinct territory, and it’s worth arriving there. Youth crave contact with adults who carry gravitas — who are accessible but exude stability, wisdom, and welcome authority. But it’s harder for young adults to lend trust to would-be mentors when they’re dressed identically to their peers.

Why Men Should Dress (at Least a Little) Differently Than Boys

Despite the sweeping arguments above, I’m not advocating for men to return to wearing three-piece suits on the daily. I don’t even live out the “men don’t dress like boys” maxim very strictly myself. As mentioned, most days, you’ll find me wearing jogger pants and a t-shirt while working from home or running errands.

But, I do always try to dress a little nicer — and a little more maturely — any time I’m doing something that rises above grabbing groceries. And I do think it would benefit individual men, and the culture as a whole, if men dressed differently than boys — even just a little.

I’m envisioning a world where Dad’s clothes are just a bit more tailored and structured than Junior’s. Where, even in casual settings, a man is more likely to wear jeans than sweatpants, more apt to reach for polos, camp shirts, and Oxford button-downs than t-shirts. And when he does wear a t-shirt, it’s a solid-color, classic-looking one. In nicer settings, where he can get away with putting his toddler in a polo, he still wears a suit himself. He doesn’t wear Air Jordans or flip-flops past age twenty-five. He finds subtle ways to signal that manhood is a different stage of life than boyhood — and that he’s entered into it.

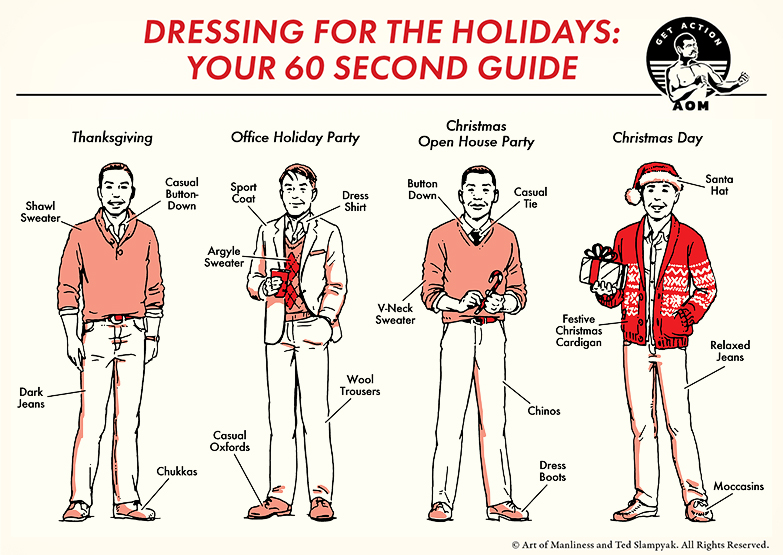

For help dressing like a grown man — without having to don a top hat — check out our decade-by-decade style guides in the AoM archives:

- A Man’s Guide to Dressing Sharp and Casual in His 20s

- A Man’s Guide to Dressing Sharp and Casual in His 30s

- A Man’s Guide to Dressing Sharp and Casual in His 40s

- A Man’s Guide to Dressing Sharp and Casual in His 50s

For even more age-appropriate, casual style inspo that doesn’t involve elastic pants and Crocs, also take a gander at our smart casual dressing guides:

- A Man’s Guide to Smart Casual

- Summer Smart Casual: 3 Getup Ideas for the Office, Date Night, and Weddings

Clothing has always been part of the way young men have made the transition into manhood. When you act like a man, you feel like one. When you dress like a man, people treat you as such. And when enough men do both, the culture benefits from having a few more adults in the room.