Note: My guest in this episode, Dr. Earle Labor, died on September 15 at the age of 94. Earle was the world’s foremost authority on one of the Art of Manliness’ guiding inspirations and lights: Jack London. Earle dedicated his career to London scholarship and his work was pivotal in turning London’s literature into a subject of serious study. Earle taught the very first undergraduate and graduate courses devoted to London and penned a hundred articles and ten books about him.

The literature of Jack London has long been given the short shrift by scholars. They say he wrote some good dog stories for boys, but beyond that didn’t showcase any literary genius or high-level craftsmanship. Well, my guest today begs to differ with this assessment.

His name is Earle Labor. He’s the preeminent Jack London scholar and 91 years young. I’ve had Earle on the podcast two previous times: the first to discuss his landmark Jack London biography, and the second to discuss his own memoir, The Far Music. For this episode, I drove down to Earle’s home in Shreveport, Louisiana to talk to Earle about the overlooked literary genius of Jack London and the big themes that London wrote about in his novels and short stories. We begin our discussion with Earle’s story of how he became a Jack London scholar and why London’s work was historically neglected by academics. We then dig into London’s literary themes by first discussing how he used the Klondike as a symbolic proving ground for men and how success in this wilderness depended on one’s ability to mold oneself to Jack’s “Northland Code.” Earle uses excerpts from my favorite London story, “In A Far Country,” as well as “To Build a Fire” and The Call of the Wild, to showcase the tenets of this code, and well as London’s literary artistry.

Earle then explains how London shifted his themes later in his career with his agrarian writing, how his wife Charmian changed his perception of real women and his female characters, and the influence that psychiatrist Carl Jung had on London’s last works.

Consider this episode a masterclass on the literature of Jack London.

Resources Related to the Episode

- Earle’s biography of Jack London

- My first interview with Earle about Jack’s epic life

- My second interview with Earle about “The Era of Bright Expectations”

- Martin Eden

- The Libraries of Famous Men: Jack London

- Jack London’s Wisdom on Living a Life of Thumos

- “The Symbolic Wilderness” by Gordon Mills

- “To Build a Fire”

- “In a Far Country”

- Descriptions of Manliness: Jack London

- AoM series on Jack London’s life

- “The Sentinel” by Arthur C. Clarke

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay:

Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. The literature of Jack London has long been given the short shrift by scholars. They say he wrote some good dog stories for boys, but beyond that, didn’t showcase any literary genius or high-level craftsmanship. Well, my guest today begs to differ with this assessment. His name is Earle Labor. He’s the preeminent Jack London scholar and 91 years young. I’ve had Earle on the podcast two previous times, the first to discuss his landmark Jack London biography, it’s episode number 67, and the second time to discuss his own memoir, The Far Music, and that’s episode number 370.

For this episode, I drove down to Earle’s home in Shreveport, Louisiana, to talk to Earle about the overlooked literary genius of Jack London and the big themes that London wrote about in his novels and short stories. We begin our discussion with Earle’s story of how he became a Jack London scholar and why London’s work was historically neglected by academics. We then dig into London’s literary themes by first discussing how he used the Klondike as a symbolic proving ground for men and how success in this wilderness depended on one’s ability to mold one’s self to Jack’s Northland Code. Earle uses excerpts from my favorite London story, In a Far Country, as well as To Build a Fire and the Call of the Wild to showcase the tenets of this code as well as London’s literary artistry.

Earle then explains how London shifted his themes later in his career with his agrarian writing, how his wife Charmian changed his perception of real women and his female characters, and the influence psychologist Carl Jung had on London’s last works. Consider this episode a masterclass on the literature of Jack London. After it’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/london.

All right, Earle Labor, welcome back to the show.

Earle Labor:

Thanks, Brett. It’s great to be here again.

Brett McKay:

We had you on, I’m going to say six years ago to talk about your Jack London biography. Then we had you on again to talk about your memoir, The Far Music, which I know a lot of our listeners enjoyed. This time, I’ve made a trip down to Shreveport, Louisiana, to come shake your hand because I wanted to meet you after all these years, and then to talk more about Jack London, particularly about the literary themes of Jack London because that’s what you spent your career writing about, researching about, lecturing about was Jack London and his literature. I think the first question I’d like to start off with is how did you become a Jack London scholar?

Earle Labor:

I’m going back to 1948, Brett. A professor at SMU named George Bond taught a course in the American Novel. Among the novels he chose, not only Hemingway and Faulkner and Fitzgerald, he chose an obscure novel by Jack London titled Martin Eden. My best friend, P. B. Lindsay, a combat veteran from the second World War, a couple years older but much older in many ways, took that course and told me, “Earle, Martin Eden is a very powerful novel. You need to read it.”

At that time, I had some other interests, mostly extra-literary, but four years later, I’m on a weekend pass to New York City from the recruit training center in Bainbridge, Maryland. Downtown Manhattan, just strolling around, looking at the sights, walked into this newsstand, and saw a 25-cent Penguin paperback of Martin Eden. Well, my friend had recommended it, I thought I’d look at it. I took it down, bought it, put it in my hip pocket to take back to the bus. I started reading it on the bus back to the base. Could not put it down, Brett. I stayed up all night, I didn’t mudden up, exactly, I stayed in my bunk with my flashlight on. I was so fascinated with that novel. I said, “When I go back to get a PhD, Jack London is going to be my subject.” That was the beginning of my serious study.

Now, it was a while before I got to that because I had some other obligations at the time to Uncle Sam in the military training recruits at that base in Maryland. Also, I spent some time on a USS AO destroyer. But when I got out of the Navy, I had a family, a wife and a child, and I had to have a job. So I went to work for Haggar, a company in Dallas, men’s slacks. I was really lucky in terms of that was an up and growing company. I found that the intellectual challenge of men’s pants wore a bit thin after about six weeks. I was doing okay from their point of view but I wanted to get back into teaching.

So, the same professor, George Bond, called me one Saturday morning in early 1955, and said, “Earle, there’s a little liberal arts college over in Shreveport looking for an instructor. If you’re interested in getting back into teaching, I’ll recommend you.” Three weeks later, I was teaching at Centenary College. I’ve been teaching on and off at Centenary ever since then, though my retirement a few years ago. Took off a few years for various things I may have mentioned in some of my early work, such as a Fulbright lectureship in Denmark for a year, et cetera, et cetera. Mainly I’ve been teaching and working on Jack London ever since.

Brett McKay:

For your PhD, you did the first major study on Jack London as a true literary artist. You were really breaking new ground because for a long time, the literary establishment didn’t take London’s work seriously. Very few scholars had studied his craftsmanship. Why was that and what’s the status of London today in literature, particularly in terms of scholarship?

Earle Labor:

Well, it’s on the rise, for sure, has been for the past generation or so. It’s amazing to see what’s happened in the last couple of decades, but for a long time he was dismissed as little more, as I say, then a hack writer for adventure stories and what have you. Fortunately, there have been a number of breakthroughs just in the last two or three decades. Actually, to be honest, Brett, I think over the past half century or so, I have a lecture that I give sometimes on the politics of literary reputation and I explain to my students, I said, “Look, the books you read, the ones you read in high school, and many that you read in college, were not handed down to Moses on that tablet. They are selected by a certain group. Those are the so-called elite, they decide what you’re going to read. They decide, for example, you’re going to read Shakespeare and maybe I’ll thrown in Scarlet Letter, which is fine, but they should be also assigning Jack London’s The Sea Wolf, or something in addition to The Call of the Wild.”

Anyhow, London was not a part of the group that makes those decisions. Now, for one thing, London was a western writer and they were not part of the eastern establishment that pretty well dictated the literary selections or whatever at the time in the 19th and even 20th century. Eric Miles Williamson uses the term “the Ivy Mafia,” that may not be quite fair, but I think it’s kind of fun. Anyhow, the idea that it’s those easterners back in the 19th century, even early 20th century, centered around Boston and New York, William Dean Howells was the leader of that group for a generation.

Interesting that he encouraged writers like Hamlin Garland and Stephen Crane, even Emily Dickinson. Here is London, at the time, the most popular of all of them, and virtually ignored by William Dean Howells. Now that’s got to have been deliberate, I think. All of that ties into what I call the politics of literary reputation, which has impeded the recognition of Jack for a number of years, but finally we’re getting that recognition as a result of what’s been done over the past 50 years and certainly the last generation.

My own student, Jeanne Campbell has become Jeanne Campbell Reesman, started the Jack London Society in about 1990 or so. Ken Brandt is currently the executive director of that. Just in the last few years, the Modern Language Association has published a collection of essays on London called “Teaching Jack London” that have been edited by Ken Brandt and Jeanne Reesman, has over 20 essays by different scholars. Even more recently, the Oxford University Press has published a handbook of Jack London edited by Jay Williams that has more than 30 essays by different scholars in there, which says something about what’s happening to Jack London and his status during the last decade or two.

Brett McKay:

So, yeah, he’s on the rise. Let’s talk about some of the themes that Jack London wrote about during his career. We’ll get into detail about some of these themes, but before we do that, could you give us just a big picture overview, sort of an outline of the themes that he wrote about, both in his fiction and in his non-fiction?

Earle Labor:

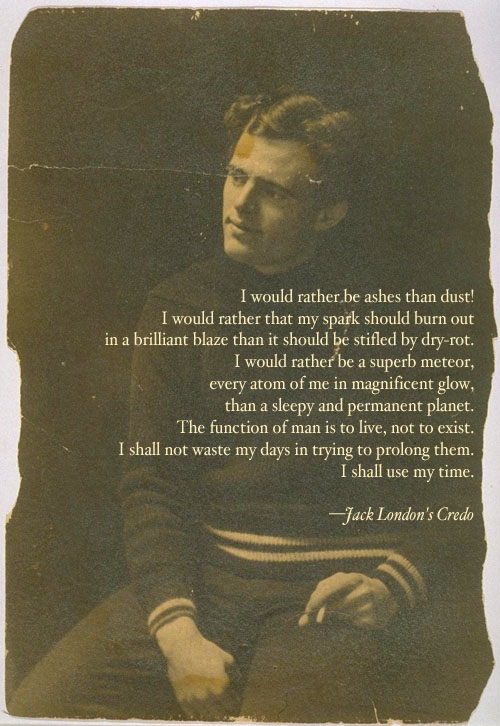

I’m looking here, and I’ll simplify in just a minute, I was just looking at my introduction to The Portable. Thematically, London’s work’s moved from the foolishness of pride, ruthlessness of greed, blindness of racial prejudice, and the senselessness of war to the indomitability of the human spirit, the unfailing salvation of true comradeship, and the ageless wisdom of The Great Mother and The Water Baby. I could talk later about The Great Mother archetype and The Water Baby, which is London’s last story, which is very revealing, but in more general terms, I like to say that one of the overriding themes is love, love of adventure, love of life, love of humanity, love of nature, love of man for woman, comradeship, camaraderie, love of seeking, and what have you. It’s a kind of passion that he has.

In my biography, I’ve talked about the seeking drive, for example, that London had in extreme measure that the neuroscientists have discovered a generation ago is that basic drive along with fear and hunger, sex and the rest of it, that leads mammals to seek new adventures even at the expense of food and fear, sometimes. Anyhow, what’s fascinating to see is it work. I’m trying to think of other things. Of course, the hatred of anything that was restricting that deprived human beings of their essential humanity and liberty or what have you. Those seemed to be themes that run throughout his work.

Brett McKay:

One theme that he, I think it was a common theme throughout all his work, is this idea of man versus nature. Nature being sort of a proving ground for men. I think you’ve written about this, that as nature, there’s four types of environments that London wrote about where you see this motif of man versus nature. Can you talk a bit about that?

Earle Labor:

Are you talking about symbolic wilderness?

Brett McKay:

Symbolic wilderness.

Earle Labor:

Yeah, I’m going back now about, what, 50 more years. A University of Texas scholar named Gordon Mills published a very fine article in 19th century fiction on the symbolic wilderness contrasting in James Fenimore Cooper’s version of that wilderness with Jack London’s, saying that Fenimore Cooper’s wilderness was pretty consistent and what have you, but that Jack London’s version of the symbolic wilderness was confusing and didn’t seem to have any sense of organization or what have you.

I thought about it, I said, “Well, I don’t think Gordon Mills has read Jack London’s work carefully enough.” There are four different versions: the Northland; then there’s the Polynesia, which I call London’s Paradise Lost; and there’s Melanesia, which I call the Inferno; and there’s the Valley of the Moon, which is Jack London’s pastoral wilderness or what have you. Each has its own distinctive characteristics.

The qualities that a man needs to survive in the Northland are totally different from what he needs to survive in Melanesia. The Northland, I think these are spelled out pretty clearly in the opening of In A Far Country. I think one of your own favorite stories-

Brett McKay:

My favorite story.

Earle Labor:

If you give me a minute, I’d like to read that here.

Brett McKay:

Let’s do it because it’s my favorite thing that Jack London ever wrote.

Earle Labor:

Brett, this spells it out. I’m reading the beginning of In A Far Country, which I call an exemplum. In other words, if a preacher’s delivering a sermon, he wants to tell a story, a pretty dramatic story to illustrate his sermon. That’s sometimes called an exemplum and that’s what we’ve got In A Far Country. Here’s the sermon.

“When a man journeys into a far country, he must be prepared to forget many of the things he has learned and to acquire such customs as are inherent with the existence of the new land; he must abandon the old ideals, the old gods, and oftentimes he must reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped. To those who have the protean faculty of adaptability, the novelty of such change may even be a source of pleasure; but to those who happen to be hardened in the ruts in which they were created, the pressure of the altered environment is unbearable, and they chafe in body and in spirit under the new restrictions which they do not understand. This chafing is bound to act and react, producing divers evils and leading to various misfortunes. It were better for the man who cannot fit himself to the new groove to return to his own country; if he delay too long, he will surely die.

The man who turns his back upon the comforts of an elder civilization, to face the savage youth, the primordial simplicity of the North, may estimate success at an inverse ratio to the quantity and quality of his hopelessly fixed habits. He will soon discover, if he be a fit candidate, that the material habits are the less important. The exchange of such things as a dainty menu for rough fare, of the stiff leather shoe for the soft, shapeless moccasin, of the feather bed for a couch in the snow, is after all a very easy matter. But his pinch will come in learning properly to shape his mind’s attitude toward all things, and especially toward his fellow man. For the courtesies of ordinary life, he must substitute unselfishness, forbearance, and tolerance. Thus, and thus only, can he gain that pearl of great price – true comradeship.”

That’s the key, I think, to the Northland Code and the In the Far Country has dispelled that I cannot do that. They totally unfettered to come up there in the first place and they paid the price.

Brett McKay:

What I love about the into to In A Far Country is that it perfectly encapsulates and summarizes Jack London’s, what you call the Northland Code. From what you just read there, part of the Northland Code is adaptability.

Earle Labor:

Exactly.

Brett McKay:

It’s also true comradeship.

Earle Labor:

Exactly.

Brett McKay:

Those seem to be the two important things for London when it came to the Northland Code.

Earle Labor:

Both are important. There’s another factor he doesn’t mention here, he mentions later. In addition to adaptability, camaraderie, what have you, all that, there’s another factor that comes up very clearly in that great classic, To Build a Fire. We’re talking about the man who does not have a name in this version. Incidentally, I’ve seen the original manuscript and at first, when he started this story, Jack London gave the man a name. I think, as I recollect, something like John Collins, but after about a thousand words, meaning after, I think, the first day, he comes back and says, “This story would be more effective if I made this every man instead of a specific man.”

Now, by the way, you know there’s an early version of the story that King Hendricks and I found in the summer I was working with him out at Utah State, that was published what, say six years earlier, and used companion. Totally different remiss by the same title, but the young man in there is given a name and he survives, but this guy’s not going to make it and here’s why.

By the way, London opens this story talking about how weird the situation is up there, very, very cold 70-something degrees below zero, no sun in the sky. “But all this—the mysterious, far-reaching hairline trail, the absence of sun from the sky, the tremendous cold, and the strangeness and weirdness of it all—made no impression on the man. It was not because he was long used to it. He was a new-comer in the land, a chechaquo, and this was his first winter. The trouble with him was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significances.

Fifty degrees below zero meant eighty-odd degrees of frost. Such fact impressed him as being cold and uncomfortable, and that was all. It did not lead him to meditate upon his frailty as a creature of temperature, and upon man’s frailty in general, able only to live within certain narrow limits of heat and cold; and from there on it did not lead him to the conjectural field of immortality and man’s place in the universe.”

Now, this is a master stroke of the artist. In other words, here’s a story that’s so deftly and beautifully woven together, the reader doesn’t realize that suddenly there’s a profound philosophical message in this story. It’s more than about just a man’s getting cold and dying from freezing to death, but there’s another message underlying this, which he’s just slipped in there, but he’s done it so deftly, so artistically, you read right on through it and don’t stumble over it. It’s a wonderful example of what London was doing.

Later on, I’ll talk about how he does that in The Call of The Wild, but anyhow. I wanted to bring in as a factor, and he mentions that other places, too, the importance of imagination if you’re going to make it up there. Later on, when he’s talking about survival in Melanesia, he said one of the things there to survive, whoever going to make it doesn’t need any imagination, he just got to be as mean as the savages around there and resort to stuff as bad as they do. Totally different from the Northland.

Brett McKay:

So, back to this idea of imagination and going back to In A Far Country, I think it’s related to one of the things that seemed to be wrong, or something that London talks about, not only In A Far Country, but you see it in The Call of the Wild, White Fang, London went up to the Klondike when people were going up there for the Gold Rush. But in his stories, he talks about one of the problems with the incapables and some of the other characters who don’t fare well in the Klondike, is that they went up there with impure intentions, almost. They didn’t have the right intention. Like with the incapables, London said they had sentimentality about the Klondike but they didn’t have the spirit of true romance and adventure. What was the difference in London’s mind between those two?

Earle Labor:

In London’s mind, sentimentality is this illusion that you’re going up, having a beautiful, a lovely time out with nature or whatever, going to have a pretty easy time just enjoying the beauties of nature without really understanding the reality of the situation. That’s, I think, Percy Cuthfert, is the dilatant who thinks that he’s read a lot of romantic stuff about the animals, et cetera, it’s going to be some kind of winter wonderland, which of course it’s not. The other was Carter Weatherbee, I think, is going just for strictly materialistic gain or whatever, thinks he’s going to become a millionaire without having to do too much to achieve that. The idea of true adventure, I’m going back to see again. You want to go regardless of the danger and you want to find out what the new frontiers are like, you’re willing to go ahead, even risk your life, to grow, to find out what your limits might be and test them, find out what nature’s really like, speaking realistically.

Brett McKay:

In The Far Country, you’ve written about this, you make the case that the incapables, as you call them, London used those characters as a way to explore the seven deadly sins. What was going on there? Was this actually a sermon?

Earle Labor:

I had fun with that, but if you give me a minute-

Brett McKay:

Sure.

Earle Labor:

… I’ll take it out here. After no meager show of industrious cooperation, they abandon the austere discipline of the code. Discipline is the key. Their spiritual degeneration as they succumb to each of the seven deadly sins is initially dramatized in their social relationship. First, pride is manifest in a foolish arrogance that precludes the mutual trust requisite to survive in the wilderness. Mutual trust also a key there. I’m quoting here, “The one was a lower-class man who considered himself a gentleman, and the other was a gentleman who knew himself to be such. From this, it may be remarked that a man can be a gentleman without possessing the first instinct of true comradeship.

Next appears lust, as they consume with sensual promiscuity, their supply of sugar, mixing it with hot water and then dissipating ‘the rich white syrup’ over their flapjacks and bread crusts. This is followed by sloth as they sink into a lethargy that makes them rebel at the performance of the smallest chore, including washing and personal cleanliness, and, for that matter, common decency. Accelerated by gluttony, their moral deterioration now begins to externalize itself in their physical appearance. I’m afraid they were not getting their proper shares and in order that they may not be robbed, they fell to gorging themselves. In the absence of fresh vegetables and exercise, the blood became impoverished and a loathsome purplish rash crept over their bodies. Next their muscles and joints began to swell, the flesh turning black while their mouths, gums, and lips took on the color of rich cream.

Instead of being drawn together by their misery, each gloated over the other’s symptoms as the scurvy took its course. Covetousness and envy appear when they divide their sugar supply and hide their shares from each other, obsessed with the fear of losing the precious stuff. The last of the cardinal sins, anger, is delayed a while by another trouble, the fear of the north.” Finally, at the very end, that’s when they kill each other, at the very end of the thing. That’s the anger. So, anyhow, there’s a lot in between there, but that gives you at least a rough idea. As I say, I was having some fun just playing with that. That story, I think, is one of his underrated story. It says so much about the code and also about London’s literary artistry.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, I agree. You mentioned The Call of the Wild. That’s in the news. They’ve got a new movie coming out based on The Call of the Wild, Disney does, starring Harrison Ford. What themes does London talk about in The Call of the Wild that you think hit on the idea of the Northland Code?

Earle Labor:

Well, we’re back again to adaptability in The Call of the Wild. That’s certainly one reason that Buck is able to survive because he adapts even though it requires him to become something very different from what he was as the sort of pet ranch dog down on the ranch down in California, et cetera. Kind of the code that I think animals live by is different from Northland Code that men live by, in some ways. For example, with animals and with Buck, sometimes he has to kill to survive, and that’s not generally the case with the men in the Northland Code.

But let’s go back after he managed and he has the will to take over, to take control of the team and what have you. He’s tough, he’s strong, but he’s gotten spirit and finally, though it’s love that prevails, it’s his love for John Thornton that really saves him at the end. Of course, to become what the supernatural ghost dog of the north, he has to even leave John Thornton and I want to talk at some point about The Call of the Wild and the fact that there’s so much more than just a dog story, whenever you’re ready to do that.

Brett McKay:

Let’s move right into that. Let’s talk about that. Go ahead.

Earle Labor:

Let me talk a little bit about the universal appeal of this novel. It’s been translated into nearly a hundred different languages, I think. It’s obviously more than a good dog story. It’s that but much more. I want to talk about The Call of the Wild as such a rich work in terms of thematic richness and also literary artistry. The first six chapters are pretty matter of fact. I think the book starts with something, “Buck did not read the newspapers.” That’s pretty matter of fact. Interesting, he didn’t say that Buck can’t read. He just said, “Buck did not read the newspapers.” That’s stating matter of fact.

The first six chapters are quite realistic and what have you, but there’s one section that is outstanding and I want to read that. “There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive. This ecstasy, this forgetfulness of living, comes to the artist, caught up and out of himself in a sheet of flame; it comes to the soldier, war-mad on a stricken field and refusing quarter; and it came to Buck, leading the pack, sounding the old wolf-cry, straining after the food that was alive and that fled swiftly before him through the moonlight. He was sounding the deeps of his nature, and of the parts of his nature that were deeper than he, going back into the womb of time. He was mastered by the sheer surging of life, the tidal wave of being, the perfect joy of each separate muscle, joint, and sinew in that it was everything that was not death, that it was aglow and rampant, expressing itself in movement, flying exultantly under the stars and over the face of dead matter that did not move.”

I think that’s poetry there. It’s interesting that he talks about that affect. I quote it in my biography in terms of Jack’s own ecstasy in writing. He had a passion that I think enabled him to write some of his best work there. I think more than one writer has talked about being in a kind of zone when you’re writing.

We had a visitor on campus a few years ago said that the scientists actually measured, there’s a slight increase in brain temperature when we get into that creative zone. Anyhow, let me move quickly as possible to the seventh chapter, the Sounding of the Call. By the way, seven is the most significant of numbers archetypally-speaking, signifying the completion of a cycle and some other things. What has begun up to this point, very matter of factly, note how the language changes at the very beginning of this seventh chapter.

“When Buck earned sixteen hundred dollars in five minutes for John Thornton, he made it possible for his master to pay off certain debts and to journey with his partners,” that’s pretty matter of fact, but note what happens here. “… journey into the East,” that’s capitalized, “after a fabled lost mine, the history of which was as old as the history of the country. Many men had sought it; few had found it; and more than a few there were who had never returned from the quest. This lost mine was steeped in tragedy and shrouded in mystery. No one knew of the first man. The oldest tradition before it got…”

Anyhow, I’m going to stop and move down a ways. Look at those keywords like fabled and tragedy, mystery, that indicate we’re in a different world now, we’re moving into a kind of supernatural world, and note at the bottom of that page. “The months came and went, and back and forth they twisted through the uncharted vastness, where no men were and yet where men had been if the Lost Cabin were true. They went across divides in summer blizzards, shivered under the midnight sun on naked mountains between the timber line and eternal snows, dropped into summer valleys amid swarming gnats and flies, and in the shadows of glaciers picked strawberries and flowers as ripe and fair as any the Southland could boast. In the fall of the year they penetrated a weird lake country, sad and silent, where wild-fowl had been, but where then there was no life nor sign of life – only the blowing of chill winds, the forming of ice in sheltered places, and the melancholy rippling of waves on lonely beaches.”

That’s poetry again, but here’s the point that I wanted to make. Stop and think what these guys have been through and what they must look like. I’d be interested in seeing what Harrison Ford and his partners look like in the movie there. They’ve got to be pretty tough hombres to survive what they do up there. You can imagine if they see some wild strawberries out there, they haven’t eaten anything except probably dried beef or something for a good while, jerky or whatever, they eat some strawberries, but they’re picking flowers. It just doesn’t fit, does it? But you don’t notice because he’s woven this thing so well in terms of describing. You don’t stumble over that at all. I’m talking this is an instance of London’s literary artistry and the way he weaves these moods for you. So I just wanted to point that out in terms of The Call of the Wild.

Brett McKay:

So the relationship between man and nature that Jack experienced in the Klondike was more adversarial, but he also experienced a different relationship between man and nature through his work on his dude ranch in Glen Ellen, California, where he was a pioneer in organic farming and he tried to make what was worn out land fruitful again. What books did Jack write about his ranching and farming experience?

Earle Labor:

Three novels particularly, the first was Burning Daylight and the second one’s Valley of the Moon, that’s his longest novel, and the third was Little Lady of the Big House. Burning Daylight, I think is his most neglected novel. I like it. As far as I know, Brett, it’s the only novel in which the major character epitomizes all three American archetypal heroes. The hero is frontiersman, the hero is a business man, the hero is yeoman farmer, all in one character. I think it’s amusing. I’m not saying it’s one of his great novels but it’s fun to read, to see what he does.

Brett McKay:

In these agrarian stories, did Jack London develop a code similar to the Northland Code that someone had to live by in order to thrive as a farmer?

Earle Labor:

I think so in terms of camaraderie, decency, honesty, but love of land here is an interesting story. His first story that he wrote after moving into the valley of the moon, 1905 or so, all go canyon. And you’ve got this character, Bill, who is a prospector on some place like the ranch down there, prospecting for gold, and he finds this big gold pocket and desecrates the hillside to get the gold. In the process, almost gets killed by a stranger that’s been watching him and Billy uncovers the gold and he comes up and shoots him. Fortunately, he manages to survive, but you’ve got something of the Northland-type coming down there, not loving the land, you see, but desecrating that beautiful place. So there’s a message there that Jack is trying to convey that he is getting the same attitude in terms of treatment of nature. Doesn’t work in the pastoral wilderness the way it did in the frozen Northland, but in terms of the spirit, camaraderie, decency, honestly, love of man and what have you, it’s essentially the same.

Incidentally, we might mention that London’s attitude toward women changed significantly after meeting Charmian from what it was in the early stuff. You want to talk about that some time?

Brett McKay:

Let’s talk about that right now. He was married twice. His first wife, they separated.

Earle Labor:

Right.

Brett McKay:

Then he met Charmian. Tell us about their relationship and how it influenced his writing.

Earle Labor:

He married Bessy Maddern for the wrong reasons. That was a terrible mistake for everybody. We’re still paying the price in terms of the damage to the folks, to the offspring, all that. It’s so sad. At first, neither of them really loved each other. It was a marriage of convenience. She had just lost her fiance, Fred Jacobs, to, I think, some kind of ailment when he was on a cruise ship going to the Philippines. I forgot now what he was suffering from. But they had been friends for years and he felt, “Well, I need to get married and settle down and have a good mother for seven Anglo-Saxon sons,” or whatever. Turned out that Bessy did love him but he never really loved her. They had two daughters. Meanwhile, he was having kind of an affair with Anna Strunsky. I mean, never consummated but in terms of somebody he could relate to intellectually and personally more closely than he could with Bessy. He was a party guy. He loved fun and loved crowds and what have you and loved to entertain people and Bessy didn’t like that at all. So they were just not compatible.

Finally, I guess it was summer of 1903 or so, he fell in love with Charmian and madly, literally madly in love. You read my biography, you’ll see some of those early love letters where he was just absolutely beside himself. He never met a woman quite like that. I wish it handy, I could describe her. She was the new woman in many ways. She was very feminine but the same time she was tough, she had a will of her own, but she was smart enough to know how to get along with him. She was very attractive, which does come out in her pictures. Milo Shepherd, Jack London’s great-nephew, knew her very well for many years and had tremendous admiration for her. He said even when she was in her 60s, she could turn men’s heads when she walked in a room.

Charmian was something special and that’s from her that he evolved the idea of the mate woman. Not just in any kind of animalistic sense or whatever, but a true mate in terms of an equal in many respects. Loved her until the day he died and she loved him, of course. Speaking of being attractive, Houdini had an affair with her after his death, wanted to marry her, but she didn’t want to marry Houdini. In fact, she didn’t want to marry anybody after Jack, I guess.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, this idea of mate woman. They called each other mate. How do you see this idea of the mate woman? Does it come up in London’s literature, in his stories?

Earle Labor:

Oh, yeah, yeah. It comes up, let’s see, I think in Burning Daylight. In one sense, it comes up in the Sea Wolf with Maud Brewster as his mate. Maud, I think, may be the first character in his novels based on Charmian. It’s certainly there. At some point, by the way, you mentioned London’s concept of masculinity.

Brett McKay:

Yeah.

Earle Labor:

I think that’s very important. There’s a section I’d like to read about that pretty soon, but let me mention characters that exemplify masculinity. John Thornton, of course, in The Call of the Wild; Weedon Scott in White Fang; and I think even Humphrey van Weyden in the Sea Wolf. It’s fascinating, particularly in the Sea Wolf, because Humphrey is a work in progress. He comes on board Wolf Larson’s ship, the Ghost, as a kind of neuter, a sissy, and Larson makes a man out of him. Larson’s too much of a man. There’s a section in the Sea Wolf where Humphrey is talking about these guys, they need a little influence of women there, their world is warped, in a sense.

Here is Wolf Larson making a man, in a sense, giving Humphrey that masculinity, but he needs something else, he needs that feminine touch, and that’s where Maud Brewster comes in to make him the complete man. There’s a section even in To the Man on the Trail I wanted to read to you when we get a chance. Shall I do that now?

Brett McKay:

Well, let’s do that. Let’s talk about that. Let’s do that.

Earle Labor:

All right. I’m back to very early story, the first story he published in the Overland Monthly, To the Man on the Trail. By the way, Malamute Kid, who’s the kind of high priest of the Northland Code is another example of the true man, or whatever. In this story, he’s a character through whose eyes we see the events unfold. Here he is.

“The talk soon became impersonal, however, harking back to the trails of childhood. As the young stranger ate of the rude fair,” by the way, this is a man named Jack Westondale who’s just come in as a man on trail to join the group. Incidentally, this is a Christmas party that’s going on in this story. Interesting, Christmas party. All right, “Malemute Kid attentively studied his face. Nor was he long in deciding that it was fair, honest, and open, and that he liked it. Still youthful, the lines had been firmly traced by toil and hardship. Though genial in conversation, and mild when at rest, the blue eyes gave promise of the hard steel-glitter that comes when called into action, especially against odds. The heavy jaw and square-cut chin demonstrated rugged pertinacity and indomitability. Nor, though the attributes of the lion were there, was there wanting a certain softness, the hint of womanliness, which bespoke the emotional nature.”

So, there you’ve got the qualities of both sexes, in a sense, both accepted qualities of masculinity and femineity in one character without having the kind of problem that you’ve got with Wolf Larson who dies, I think, symbolically as well as literally in the Sea Wolf. Also, there’s a section that Arnold Genthe talks about. This is a comment by a famous portrait artist, Arnold Genthe, describing London, as I say, most accurately. “Jack London had a poignantly sensitive face. His were the eyes of a dreamer. There was an almost feminine wistfulness about him. Yet, at the same time, he gave the feeling of a terrible and unconquerable physical force.” I think that pretty well describes London and his idea of the masculinity, as well.

Brett McKay:

Well, this idea of meeting masculine and feminine energies combined, this sounds like Jung, the psychologist, Carl Jung, and you talk about this in your biography, that at the end of his career, at the end of his life, that’s when London discovered Jung and his writings. It started to give more of an esoteric vintage-esque thinking where formerly, he was a romantic, but he was also a materialist. You make the case that we were on the cusp of some of London’s greatest work with this discovery of Jung, but you also make the case that even before, even in the Klondike stories, you see Jungian ideas pop up. Can you talk a little bit about Jung’s influence on London’s work and thought?

Earle Labor:

It’s fascinating to me, Brett, because he’s got what Jung calls the primordial vision and the stuff I just read, for example, from The Call of the Wild, indicates his sense of being tuned into myth and what have you, myth and archetypes without being conscious of it. In fact, early reviewers saw some stuff in The Call of the Wild, it was more than just a dog story. He said, “Well, I wasn’t aware of it. I didn’t intend it,” but obviously it was there and that’s the nature of the primordial vision when it’s at work. The writer feels it and writes it, creates it, without being fully aware. Much of his richest work is in form by what Jung would call archetypes and myths and what have you.

But what happened just a few months before he died, he got a copy of Beatrice Hingle’s brand new translation of Jung’s theories and he started reading that and came to his wife, Charmian, and said, “I’m standing on the edge of a world that’s so new and wonderful and terrible. I’m almost afraid to go into it.” But that’s what he’d been doing all those years. Of course, he did go into it.

The last few stories he wrote, he would deliberately employ Jungian theory. Of course, the final story, The Water Baby, which I could quote from in a moment here, is obviously Jungian, but one of his richest stories, The Red One, I thought originally, since he had written that in, I think, May 1916, that was the first story he wrote after discovering Jung, because there’s so much there that’s archetypal and mythical and is a story I recommend to everybody. It’s the same motif that Kubrick used in 2001 based on Arthur C. Clarke’s story, The Sentinel. Of course, Clarke co-wrote 2001, I think, with Kubrick.

One of my students, after reading the Sentinel in my Science Fiction Class, wrote to Clarke and got an answer. “Mr. Clarke, had you read Jack London’s The Red One?” Clarke actually answered and said, “No, but I wish I had,” you know, because the similarities. Anyhow, I recommend the story for a number of reasons, but I found out that London had not read Jung at that time, so there’s the primordial vision again, but it turns out that those half-dozen, five or six stories, he read based on Jung finally with The Water Baby are clearly based on Jungian theory. As far as I know, London’s the first one to do that.

Brett McKay:

You said you want to read something from The Water Baby to give us an idea of this. Do you want to go ahead and do that?

Earle Labor:

Yes. I totally do. Have you read it?

Brett McKay:

I have not, no.

Earle Labor:

It’s a totally different story. We’re talking now about The Water Baby, which is the last story Jack wrote before he died. It was written just a few months, I think, maybe a little more than a month before his death. It’s totally different from the other earlier stuff in that there’s almost no action, mostly it’s dialogue, between two men, a young fella named John Lakona, and that’s Jack London’s Hawaiian name, and an old man named Kohokumu, that’s Hawaiian for voice of wisdom or old man of wisdom, or what have you. They’re sitting out in a boat offshore talking and the young man has got a headache and not feeling too well. The old Native is in great shape, he’s 70-something years old, been evidently drinking at a big party the night before, raising heaven and having a good time. He’s feeling great. In fact, at one point, dives down about 40 or more feet and brings up an octopus that he’s been fishing for there. But they’re having a dialogue and the young man represents the rational, Western, civilized approach, what have you, logic and what have you. The old man is talking in terms of myth and what have you. Here’s a couple of key passages.

“So let me explain to you the secret of my birth. The sea is my mother. I was born in a double canoe, during a Kona gale, in the channel of Kahoolawe. From her, the sea, my mother, I received my strength. Whenever I return to her arms, as for a breast clasp, as I have returned today, I grow strong again immediately. She, to me, is the milk giver, the life source.” Here’s the young guy says, “Well, that’s a queer religion you got there.”

The old man says, “When I was younger I muddled my poor head over queerer religions, but listen, O Young Wise One, to my elderly wisdom. This I know: as I grow old I seek less for the truth from without me, and more of the truth from within me. Why have I thought this thought of my return to my mother and of my rebirth from my mother into the sun? You do not know. I do not know, save that, without whisper of man’s voice or printed word, without prompting from otherwhere, this thought has arisen from within me, from the deeps of me that are as deep as the sea. I am not a god. I do not make things. Therefore I have not made this thought. I do not know its father or its mother. It is of old time before me, and therefore it is true. Man does not make truth. Man, if he be not blind, only recognizes truth when he sees it. There is much more in dreams than we know. Dreams go deep, all the way down, maybe to before the beginning.”

Brett McKay:

Right, that’s Jung. So we’ve talked about different themes that Jack London hit on during his career, we talked about his Northland Code, his idea of adaptability, of true comradeship, of imagination. We’ve talked about his themes of agrarian writing and working with nature. We talked about this idea of love, love that runs through his stories. When you taught seminars on Jack London, what did you hope your students would walk away with? Some big ideas that would change their life and they would maybe think different because they read these Jack London stories.

Earle Labor:

I think maybe a sense of adventure. In other words, moving out and seeking or what have you. By the way, not just physically but intellectually seeking. There’s so much out there to be enjoyed if we’ll just look for it and open our minds to it. There’s a world of possibility in terms of relationships that we are maybe overlooking because of the various problems we’ve got socially now. We could go into what’s going on in our currently-restrictive society or what have you, but in the sense of openness and simply enjoy life while we can.

There’s so much there, which Jack was still seeking at the very end. There’s so much life has to offer if we’d just open our eyes to it and get out and experience it. I think a sense of excitement, a sense of joie de vivre, love of our fellow human beings, and maybe not just human beings but also the animals because Jack absolutely loved animals as well as people, especially horses and dogs. Those are things, I think, they may have found. Also, a general sense of excitement that they may have missed in their daily lives or whatever.

Brett McKay:

How has Jack London changed your life? You’ve spent decades.

Earle Labor:

Well, I think he’s done a lot for me in terms of relationships. It’s amazing, the places I’ve been and the people I’ve met, and the number of people out there who are absolutely taken with Jack London for one reason or another, most of what we’ve been discussing today, that there’s a sense of openness there to London that you may not find in other authors. There’s so many different possibilities for living if you just open yourself up to them.

Brett McKay:

Fantastic. Well, Earle, this has been a fantastic conversation. Thanks so much for having us here down in Shreveport.

Earle Labor:

It’s been my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Brett McKay:

My guest today was Earle Labor, he’s the preeminent Jack London scholar, also the author of the landmark Jack London biography, Jack London in American Life. Earle also wrote the forward to the re-release from Penguin Classics of White Fang, Call of the Wild, and other short stories. Both are available on Amazon.com. Just look up Earle Labor. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/london where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

That wraps another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years, including a series on Jack London. Go check that. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code “manliness” at checkout to get a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, you can download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast.

And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Stitcher, helps out a lot, and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend of family member you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AOM Podcast but put what you’ve heard into action.

Tags: Jack London