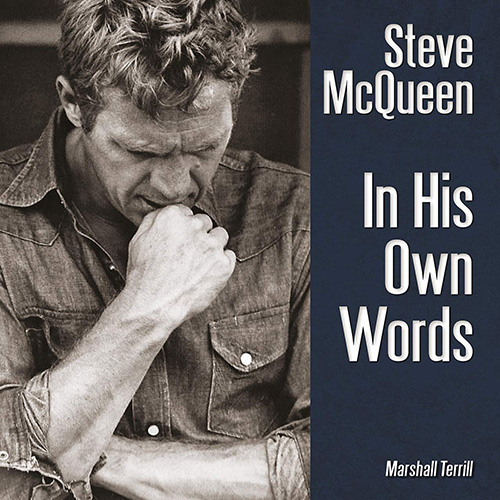

My guest has traced both sides of the coin of McQueen‘s coolness for decades. His name is Marshall Terrill, and he’s the author of multiple biographies on McQueen, including his latest, Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Today on the show Marshall and I discuss McQueen‘s enduring influence on popular culture in terms of everything from style to motorcycles, the code he lived both on and off screen, and whether after years of studying McQueen‘s life Marshall has figured out what it was that made him so cool. We then talk about McQueen‘s deprived childhood, which left him ever craving affirmation, and his youthful stints in a reform school and the Marines. We get into how he found his way into acting and then to superstardom, despite the fact he could be difficult to work with. Marshall explains McQueen‘s relationships with women, and the role race car driving played in his life. We also discuss why McQueen had a hermit phase, and how, in a lesser-known aspect of his life, he had a literal come to Jesus moment in which he became a born-again Christian. We end our conversation with McQueen‘s untimely, tabloid-exploited death at age 50.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- How big of a star Steve McQueen was and his influence on American culture and masculinity

- What made Steve McQueen so cool?

- The movie archetype that McQueen created

- McQueen’s code on and off screen

- McQueen’s hard childhood and its influence on the rest of his life

- How a stint in reform school influenced McQueen’s life

- Was McQueen a good Marine?

- How a military punishment sowed the seeds of the cancer that killed McQueen at age 50

- How did McQueen find his way into acting?

- The competitiveness and drive of Steve McQueen

- McQueen’s interest in race car driving

- What was it that made McQueen so attractive to women?

- What role did McQueen’s three wives play in his life?

- The private generosity of McQueen

- Why did McQueen step away from Hollywood for a time?

- Why did McQueen become a born-again Christian?

- The untimely and tabloid exploited death of Steve McQueen

- What Marshall has taken away from McQueen’s life

Resources/Articles/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Steve McQueen: The Life and Legend of a Hollywood Icon

- Why Men Love The Great Escape

- 100 Must-See Movies for Men (a few McQueen movies make the list)

- Style Inspiration: How Steve McQueen Rocked His Khakis

- Famous Men and Their Motorcycles

- Boys Republic

- Sanford Meisner

- Wanted Dead or Alive

- The Magnificent Seven

- Best Western Movies

- The Blob

- The Great Escape

- Cincinnati Kid

- Bullitt

- Le Mans

- Thomas Crown Affair

- Yul Brynner

- Podcast interview with Matthew Polly about Bruce Lee

- Neile Adams

- Ali McGraw

- Barbara Minty

- Junior Bonner

- The Towering Inferno

- The Old Place

- Bud Ekins

Connect With Marshall

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Performances by the actor Steve McQueen in classic films like The Great Escape and Bullitt earned him the nickname the “King of Cool.” But behind the scenes, McQueen’s character was complex in nature. He can be both difficult and demanding and kind and generous, someone who could act aloof but care about things deeply. My guest has traced both sides of the coin of McQueen’s coolness for decades. His name is Marshall Terrill and he’s the author of multiple biographies on McQueen, including his latest, Steve McQueen In His Own Words.

Today on the show, Marshall and I discuss McQueen’s enduring influence on popular culture in terms of everything from style to motorcycles, the code McQueen lived, both on and off screen, and whether after years of studying McQueen’s life, Marshall has figured out what made him so cool. We then talk about McQueen’s deprived childhood, which left him ever craving affirmation in his youthful stints in a reform school and the Marines. We get into how he found his way into acting and then to super-stardom, despite the fact that he could be very difficult to work with. Marshall explains McQueen’s relationships with women and the role race-car driving played in his life. We also discuss why McQueen had a hermit phase and how, in a lesser known aspect of his life, he had a literal come to Jesus moment in which became a born again Christian. And we end our conversation with McQueen’s untimely, tabloid-exploited death at age 50. After the show’s over, check at our show notes at aom.is/McQueen.

Alright, Marshall Terrill, welcome to the show.

Marshall Terrill: Hey, thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So you are a journalist and a biographer, and you’ve written several biographies of different celebrities and famous men, cultural icons. You’ve done one on Elvis Presley, Pete Maravich. You’ve done some things on Johnny Cash, but one subject you’ve written extensively about is actor Steve McQueen, the “King of Cool.” When did you start writing about Steve McQueen, and what initially drew you to him as a subject?

Marshall Terrill: I first started writing about him in the late ’80s. Now, my first book was published in 1993, but my research started in the late ’80s. He didn’t become a cultural icon at that time, but by the time my book got published in ’93, he did, so it was great timing for me. What drew me to him as a subject was because there was a connection to him as a kid. My dad was the real Steve McQueen fan. My dad just passed away in July, and he was 83 years old. And every time there was a Steve McQueen movie on television, or if there was a movie out in the theater, we’d go. And that was kind of our thing, and McQueen was his guy and so, that was the connection.

Brett McKay: So we’re gonna get into Steve McQueen’s career here in our interview, but big idea… I think… I’m 38, I’ve seen Steve McQueen movies. My parents, they grew up watching Steve McQueen movies, watched The Great Escape, Towering Inferno. But for some people, like he died before they were born, who are listening to this podcast. So can you give us an idea how big of a star he was at his peak? Like how famous was he, and what sort of influence did he have on popular culture during the peak of his career?

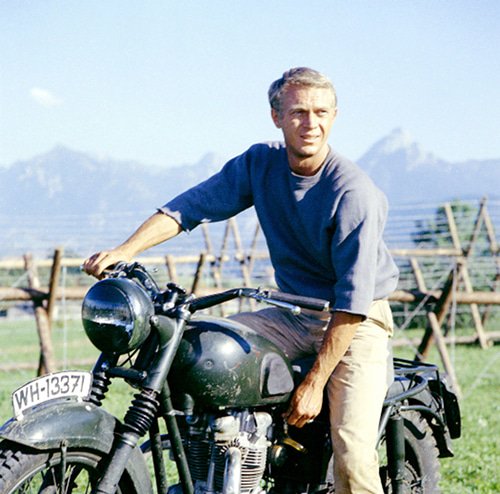

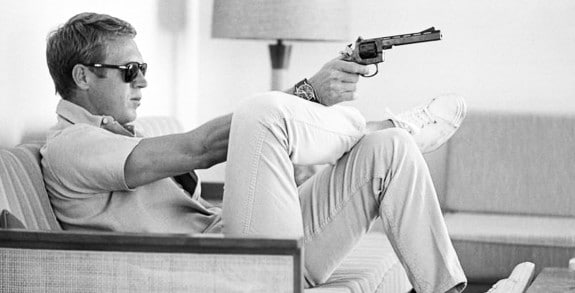

Marshall Terrill: In terms of how big of a star he was, you have to understand, back then, there wasn’t the concentration level of media and movies and streaming and DVD and television. There was a line of demarcation between television star and movie star, and he was a movie star. And there were only about, I wanna say, five to seven movie stars at that time who could open a film. And Steve McQueen was one of them. The other was Paul Newman, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, stars of those caliber got… All of them, now today, are icons. So that’s how big he was. In terms of, again, going back to popular culture, in The Great Escape, he wore this ripped t-shirt. It didn’t have a collar, or sleeves. And you could count on guys like that, wearing shirts like that. In terms of motorcycles, what he did for the motorcycle industry cannot be underestimated. He popularized it because before that, you had Marlon Brando in The Wild One, where they were outlaws.

And McQueen kind of… Even though he was a rebel, he sort of sanitized motorcycle riding because with the documentary, On Any Sunday. And then in Thomas Crown with the suits, he popularized the British cut of men’s suits. So he cut this wide swath of popular culture in terms of fashion, machinery, coolness, just… He was… He was… There’s no one today that you can really compare him to. There are elements of Brad Pitt, there are elements of George Clooney, and I would… I say even Denzel Washington in terms of acting, like if you see The Equalizer today, you can see… So, his influence really was on acting, so the influence that he has today is just, it’s tremendous, perhaps even bigger than in his lifetime.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean, still today, guys are still trying to dress like Steve McQueen. They’ll do the turtle-neck like in Bullitt with the suit… The jacket over it, the Peril sunglasses. They’re still doing that 40 years after he died.

Marshall Terrill: That’s true. Yes, that’s the fashion side, but there’s still the machinery side. There’s the Bullitt Mustang still comes out with a car every five years, and that’s strictly because of the McQueen legacy. McQueen was into antique airplane flying and antique motorcycle collecting and antique car collecting. And you know, look at how big those industries are. I mean, that’s huge, and McQueen was really kind of the first celebrity to do that.

Brett McKay: And how do you think he changed or influenced our ideas of American masculinity that we still see today?

Marshall Terrill: I would say, the influence is more in the ’60s than it is today, because what I see today in terms of masculinity, cannot be compared to a man of the ’60s, and that’s not to put it down, it’s just to say it’s changed so much. I’d say his influence really is on fashion. In terms of masculinity, yeah, it’s up there on the screen. And guys definitely wanna be like him, but in today’s society, I don’t know if you can get away with that sort of behavior. I’m not sure.

Brett McKay: Well, we’ll talk about some of his behavior, ’cause he had… He was infamous for his behavior. Before we do that, what do you think… As I was reading your biography, the thing that stuck out to me is that McQueen, when he would go into these auditions, or he’d just… And meet somebody and people would be like, “That guy’s got something, that guy is cool, there’s something about that guy, I don’t know what it is, but we gotta hire him and make him a part of this, make him the star of the movie.” In your years of researching McQueen and writing about him, were you ever able to figure out what that thing was, what made him so cool and people wanted to work with him, even though he was difficult to work with. Men wanted to be like him and women wanted to be with him. What was that thing?

Marshall Terrill: Well, it’s what they call the X-factor, and you can’t really describe it. The only thing I can come close to is, there was this animal magnetism that came out in him. He had it in real life, but he really honed it to a fine point for his movie characters. So he was what you saw on the screen, but there was also this insecure side. But in terms of what he wanted in himself as a movie star, he popularized those and he kind of… I would say he created the movie archetype of today’s modern action hero, so those were the things that people obviously wanted to emulate. But in terms of talking about the archetype, we’re talking about things like, he was the reluctant guy that got trapped into a situation, and has to get himself out. I don’t think you saw that with movie heroes of yesteryear, like John Wayne or Gary Cooper. McQueen was a different type of movie action hero, and it was more believable, and just the things that he did were unbelievably cool when he got himself out of it, so it’s really hard to put a finger on what made him cool or intriguing, other than just, you know, he had that X-factor.

Brett McKay: He was an anti-hero, that was one of the… The character he played throughout, of all of his movies, like the anti… He was kind of in it for himself, he was just there to survive for himself and get his… But along the way, he had a code that he would follow and wouldn’t cross. There’s boundaries he wouldn’t cross, even though he was looking out for number one.

Marshall Terrill: That’s correct. And you see that really, he pulls that off quite well in The Great Escape. He’s in it for himself, but at the end of it, you know that he’s gonna end up doing the right thing, and he ends up making the sacrifice for the whole squadron that was imprisoned. And so that was true, he had his own code, and a lot of his own codes in his personal life ended up on the movie screen. For example, in Wanted Dead or Alive, the writer had originally written it where McQueen beats up three guys and McQueen’s like, “No, no, no, that doesn’t happen, and here’s what you do, you back down, and then you find each one of them individually, and then you kick their butt,” and that’s what he did in The Marines. He found guys taking a leak in the latrine and then he’d blast the door open and then kick their ass. And he did it, and he found these guys one by one, but when they treaded on him, three on one, then he backed down.

So those were the types of codes that you saw in his films, and the other code is always live up to your word, never double-cross anybody and do your end. And you see that in The Getaway. There would have been a chance where he could have double-crossed the actor Al Lettieri, and he said, “No, we live up to our word, and then that way, nobody’s chasing us.” Well, they ended up trying to double-cross him anyway, but those were the kinds of things that McQueen had in his films that resonated with audiences.

Brett McKay: So, a big theme in your book, your 2010 biography, is that, to understand McQueen, and it’s not even like his coolness, like what made him cool, like that X-factor, you had to understand his childhood, ’cause that influenced his entire life. What was his childhood like, and how did it affect his personal life and his career?

Marshall Terrill: Well, the British… I’ll always like to compare his life to a Charles Dickens novel, and that’s not too far from the truth. He had… Both of his parents were alcoholics, and his father took a walk when he was six months old, and his mother was not really very loving towards him, and she was a young lady, I think she was 19 when she had him. And so, she was a party girl, and once she did give birth to him, they went to live with his grandparents, and then sometimes, she would go off on her own and then live somewhere away and then marry somebody, and then bring Steve into this hostile situation, and then he gets sent back to the farm in Slater, Missouri, with his Uncle Claude.

And so it affected him the rest of his life because he just couldn’t shake it, and so, you saw a lot of that on film. And how it shaped his compulsion to be famous was because it was miserable. He wasn’t unlike a lot of other movie stars at that time. For example, I did a book with an actor named Edd Kookie Byrnes, who did 77 Sunset Strip, and it seemed like everybody who was trying to run away or wanted to better their lives, they would just run to Hollywood, and with McQueen, it was pretty much the same.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he wanted to be loved ’cause he didn’t get that love as a kid, basically.

Marshall Terrill: Absolutely. And the ironic thing is, is that once he did get love, then he questioned it, so. But that was the interesting part of his personality.

Brett McKay: Right, that affected his relationships a lot. We’ll talk about his relations with his wives that he had, and other women as well, here in a bit, but besides living with his uncle, which he had, or that guy had a profound impact on him, taught him the importance of hard work and brought a lot of discipline and stability that he didn’t have. He also did a stint at a, like a Boystown in California, that also had a big influence on the rest of his life. Tell us about that.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, so it was called Boys Republic, and he was 14. What had happened was, is that he was getting into a lot of fights with his stepfather, and it was an untenable situation, and so his mother basically put him there and then, Boys Republic is in Chino, California, and so it’s a reform school, but without walls, without fences. And it’s kind of discipline-based, and they get up in the morning, they milk cows at 4 AM and then they do studies all day, then they milk cows again. And basically what it was, it was a little town, and they had things like city councils, and they learned about society, which was really cool.

And so McQueen had to learn to… What he said was, “I had learn to exist within it, otherwise I would have been a hood.” So it really saved his life in a lot of ways. So, it taught him discipline, it taught him how society worked, it gave him an education, even though he left by ninth grade. I’ve seen a lot of his letters, and a fairly sharp guy for a ninth grade education. His letters were very, very, very precise, to the point, and have a lot of clarity. So I was always surprised that… When you look at somebody with a ninth grade education, you think, “Oh, well,” but Steve McQueen was very, very… Not only very sharp in terms of letter writing, but he was sharp in terms of street smarts and reading people. That’s where his real intelligence came in.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and he even showed signs of that, of being able to read people, and I wouldn’t say manipulate, but influence them, even as a kid at this Boys Republic.

Marshall Terrill: Right, and some of that, too, came from him being on the street. I remember is… One of his best friends, Pat Johnson, said, “As a street kid, you have to learn to act, you have to learn how to react to people.” And here was this line that he delivered to me that I’ll never forget… He goes, “Steve McQueen was an actor way before he went to Hollywood.”

Brett McKay: Right. So he leaves the Boys, and he runs away, and then he becomes an urchin, basically, during high school… Goes to New York City, goes to different places, does odd jobs, then he did a stint in the Marines. What was his military career like? Was it long and distinguished?

Marshall Terrill: You know, the funny thing is, is that he signed for a three-year stint and he was 17 years old, and he had to get permission from his mother. And the interesting thing is, he sent about half of his paycheck home to his mother. And people always talked about how he hated his mother, but there are signs there too where he supported her and loved her, but the three-year stint… I’ve got his military file and I brought it to a friend of mine, who was a drill sergeant in the Marines, and life-long Marine guy, and looked at it, and he said, “You know, for a peacetime soldier, he did very well.”

But McQueen always liked to embellish his image as a pure rebel all the time, and so I think one of the quotes he gave was, “The only way I’d become a lieutenant is if all the other ones dropped dead and they promoted me.” But that wasn’t the case. This sergeant that I had look at his file, say that he moved up fairly quickly in the ranks and tested quite well, so it wasn’t… But then there were cases where he lied about what happened in the Marines. For example, he gave a interview with a movie magazine, and of course, the writer got a little carried away, but he talked about how he saved these people during these exercises in Labrador, and McQueen saved five people. Well, that was never in his military file.

And he always talked about guarding Harry Truman’s yacht, and then, I asked a fellow soldier who served with him about that, and he said, “You know what, Harry Truman’s yacht was on a sand bar,” and he goes, “A tree was growing through it, but if you had guard duty for it, then it sounds pretty good on your resume.” So those are the types of things that I would find. But the other interesting thing I found in his military file was that he did do 41 days in the brig for going AWOL, and it wasn’t so much for going AWOL, but when he got caught, he got caught by a police officer and they got into a fight, and that’s why he got thrown in the brig for as long as he did.

And the sad part is, part of his punishment was cleaning out the hull of a ship in the Washington DC naval yards, and in those pipes, was loaded with asbestos. And that was in December of 1949. The form of cancer that he had was called mesothelioma, and it takes 20 to 30 years to develop. And in December of 1979, that’s when he went to Cedars-Sinai to check out what was wrong with him, so it took almost exactly 30 years to develop.

Brett McKay: And we’ll talk about his death. That was the saddest part in the book, really tragic, his death. So he did the military, he got out and started kinda rambling around again. How did he stumble in… The way you describe it, is he really kind of stumbled into acting, it wasn’t something he had ambitions to do, he kind of fell into and was like, “This is great, I don’t have to work all that hard, and I get to hang out with chicks and do some work, and that’s it.” So how did that happen?

Marshall Terrill: Well, he was dating a lady who was a dancer, and she said, basically, “You’re so kooky, you’d be perfect for an actor, you should give that a try.” And so he found out that he could get acting lessons on the GI Bill, and so he went in and he was accepted to Sanford Meisner’s Playhouse, which was a very famous acting studio in New York City at that time, in the 1950s. And Meisner was one of the top acting instructors at the time. He and Lee Strasberg kinda ruled that scene. And Meisner was a little bit kinder. Strasberg could be brutal at times, but… So anyway, he got into it, discovered there are a lot of women in there. I mean, there’s no doubt that that was an influence, but then discovered that he was actually quite good and that all those odd jobs and his background fed into acting, because it gave him these experiences that he could draw on.

So, it just so happened that, okay, yeah, he stumbled upon this and all of a sudden, he discovers he’s pretty good at it. And then he got positive reinforcement, which I think is the first time he ever got that in his life. Now, he always talked about how he didn’t really care about acting, but you know, he did. As a matter of fact, I just interviewed somebody who was his roommate back in Greenwich Village when he just first started out, and he always talked about how McQueen had three and four jobs so that he could go to school. So to me, that says that he worked hard for it.

Brett McKay: It’s just a lot of things that people don’t know about him. He started off on the stage and then transitioned to television, and that was interesting, because most people when they got to television, that was a dead end. At How did Steve McQueen break the barrier from television and get into the movies?

Marshall Terrill: Well, that came with… We should probably first establish that he was on television. Wanted Dead or Alive was on CBS, and that was a top 10 television show for the first two years, then they switched it from Saturday to Wednesday night, and then it killed it. But McQueen didn’t necessarily mind that because his focus was always on the movies. And at that time there was a line of demarcation in terms of movies and television. And so McQueen had always wanted to become a movie star and so no one had really made that leap before until he starred in The Great Escape. And I say metaphorically, when he made that leap over the barbed wire fence in The Great Escape, he also made the leap from television stardom to movie stardom, and he was the first one to do so.

Brett McKay: The Great Escape, that was the movie that made him a star. ‘Cause he did a couple of other movies before The Great Escape.

Marshall Terrill: Yes, and he did The Magnificent Seven, which was a big hit. But that was starring Yul Brynner and Steve was second lead. The Great Escape was kind of the first time. That was his break-out role, and then it’s like, okay, a new star is here and he has come in a new form, and he’s not John Wayne and he’s not Gary Cooper. He is a star. He’s a new star. He’s a star for the Beatles generation.

Brett McKay: He was also in The Blob. People forget that too.

Marshall Terrill: Yes, he was. And the funny thing was, at the time, he hated The Blob, thought it would go away. And when he got his start on Wanted Dead Or Alive, the week that he got his debut on television, that’s when the people of The Blob said, “Okay, this might be a good time to debut this film.” So he was doing double duty there, but The Blob he was kind of ashamed about, and then years later on, he kind of just… He lightened up quite a bit.

Brett McKay: Alright, so The Great Escape was the movie that catapulted him to stardom. And then after that, he just had a string, like hit after hit after hit in the ’60s and into the early ’70s. At what point did he become known as… People are like, “Hey, not only is he a star, but he has transcended stardom. He is the King of Cool, and we’re gonna call him that.” When do you think that happened?

Marshall Terrill: You know, that’s the… The most ironic thing is I’ve always tried to look up who coined the King of Cool. I could never find that out, but that was definitely a term that was given to him in the ’60s, and that was because of like you said, those run of hits, which started with Cincinnati Kid, Nevada Smith, Thomas Crown Affair, The Sand Pebbles and Bullitt, so five hits back to back in a row. I’m not sure if that’s been done before or since. And then Bullitt, of course, being the biggest of all. So those things kind of enhanced his stardom, but Bullitt… I mean, he went from movie stardom to superstar. And when you enter the superstar realm, you’re in rarefied air.

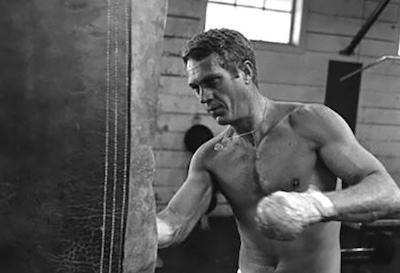

Brett McKay: So one thing you talk about throughout this book is that okay, he was a star, and he was also incredibly professional when he worked. When he was there to work, he worked. But he was also incredibly difficult to work with. He was fiercely competitive with other actors, even directors. How did that manifest itself? And why did people keep wanting to work with him, even though, for lack of a better word, he was like a complete a-hole?

Marshall Terrill: Well, the competitive part is, that’s what he had to do in order to reach the mountain top. He was willing to climb over bodies. You saw that the most in New York City. But you also saw that in the early part of his acting career. And he was a young upstart. And he didn’t go for the older actors who, like Yul Brynner, who, when he walked on the set of The Magnificent Seven, he would snap his fingers, and then there was somebody in his entourage that would place a cigarette in his hand and then a lighter to light it. McQueen just didn’t like that, ’cause he was just a rebel through and through. He didn’t go for that movie star. I mean, he loved movie stardom. He liked the perks of it, but he didn’t like acting like that.

He always wanted to forever be the rebel. He didn’t wanna be that showbizzy movie star that acted like that. So it’s interesting that he was competitive with the other actors, and he was difficult with directors. I don’t think he was difficult with directors just to be difficult. I think he knew what he wanted. And there’s a quote in my new book called Steve McQueen In His Own Words, where he talked about compromise, and he said, “If you compromise one thing, it’s up there on the screen.” So I respect him for that. And so I think he was the only guy… And he was breaking ground at the time. So he was the only guy that really knew what he wanted and how he wanted to portray himself.

So maybe the screenplay didn’t show that, but he wanted to do things that were really good for him, and Robert Wise, the director of The Sand Pebbles, said, “I never knew another actor who knew what he wanted as much as Steve McQueen did.” So, I think that’s why there was some difficulty, but in terms of why people wanted to work with him, well, that’s easy to answer. If you’ve ever met any actor in Hollywood, the next thing they do is looking for their next gig, and having a Steve McQueen film on your resume, it looks pretty good. So that’s why they continued to work with him. I just don’t think that they knew what they were in for when they did work with him.

It depended if you got in his way or not. Obviously, Yul Brynner got in his way. Frank Sinatra did not because Frank Sinatra didn’t care about being a star, and he told John Sturges, give the kid all the close-ups. But the interesting thing was, is when McQueen was now an established star, and if he thought somebody was trying to steal the picture from him, boy, they got his wrath.

Brett McKay: Yeah, there’s instances where… Steve McQueen was short. He was like 5’9″, right, or something like that. And if someone pointed that out, he’d get really… He was touchy. He had a chip on his shoulder.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, well, there’s a funny story. The director of Le Mans, his first day… Well, John Sturges was the initial director, and then another gentleman came on named Lee Katzin, and Lee Katzin was a television director, and so when he was directing his first scene, he said something to the effect of, “Now, Steve, because you’re short, I want you to stand over here.” And he did that in front of the crew. And McQueen grabbed him by the tie and lifted him up and said, “It’s Mr. McQueen to you.” And so he would do things like that to establish… Obviously, that was something that was provoked within him, but he would do things like that to establish his power.

Brett McKay: Right, so you mentioned Le Mans. That’s his race car movie. Besides being a celebrated actor, McQueen was also… He was a legitimate race car driver, a professional driver. How did he get started with race car driving?

Marshall Terrill: I think it started in New York City. He was racing on weekends to earn extra money. And then of course, when he got to Hollywood and he got the TV show, the very first thing he did was purchase a race car for racing on the weekends, ’cause that’s what he loved. He said when he got that first trophy, he got instantly hooked. And it wasn’t just a hobby for him, it was a release, and it was part of… Again, one of the quotes in the new book talks about how he wanted to have an identity apart from acting, and race car driving gave him that. But it also gave him a thrill, it gave him equilibrium, because he respected other drivers, because he said, “If you’re lousy, other people in that profession will tell you how lousy you are,” and he goes, “It makes me think that I’m not God’s gift to humanity.” So there were several reasons why he liked race car driving.

Brett McKay: There is a story in there talking about… It’s not related to race car driving, but kind of. Bruce Lee, him and Steve McQueen were buddies, and Bruce Lee, I guess, got a fancy car like a Porsche, or something like that, and Steve McQueen took him for a joy ride and scared the bejeezus out of Bruce Lee.

Marshall Terrill: What happened was, is Lee was contemplating buying a Porsche, and Lee was kinda going through the Hollywood trip himself. Now that he’d become a star in Asia, he’s growing his hair a little bit longer, he was smoking pot, he was wearing the sunglasses. So the next thing he wanted to do was… The tight blue jeans. The next thing wanted to do was buy a Porsche, and Steve said, “Well, listen, Bruce, these cars aren’t toys, and let me just take you for a test ride in mine.” And so he took him on this ride where he was doing spins and doing all these crazy things. At the end of the ride, Lee was shriveled down in the seat, this macho man, Bruce Lee.

Brett McKay: Right. The reason McQueen did that, though, was to put Bruce Lee in his place, because Bruce Lee was coming back crowing about how he was the bigger star, and making more money than Steve McQueen.

Marshall Terrill: But even better, here’s what McQueen did. Lee had written him a letter saying, “I’m a bigger star to more people across the country than you are.” He was talking about his Asian stardom. And so, the way McQueen answered that was, he sent him a signed 8 x 10, and said, “To Bruce, my biggest fan.”

Brett McKay: There’s that competitive streak there.

Marshall Terrill: That not only put him in his place, but it was just so sweet and subtle and short and to the point.

Brett McKay: So McQueen, besides being a famous actor, he was a sex symbol. Women flocked to him, and this got him into trouble, and you talk about his marriages. What do you think the appeal was with women? Why do you think women were so drawn to Steve McQueen?

Marshall Terrill: Well, again, it goes to that X-factor. I kinda draw correlation between me and my brother, Mark. I’m an okay-looking guy, but Mark is a… He has something about him. He’s chiseled, he’s got this animal quality. I remember this one lady who was a friend of mine just like, “Who’s that?” And I say, “That’s my brother,” and she goes, “Oh, man, he’s like a wild animal.” I think women pick up on that, and I think with Steve McQueen, that was what he was. He was just like this feral animal that had to be tamed and women just… They went crazy over that. Now, there was a price to be paid for that. They could have a short-term relationship with him, and that would work out just fine, but the women that had long-term relationships with him, that didn’t work out so well.

Brett McKay: Right. What’s interesting about Steve McQueen is that he was very liberal with his relationships, privately. But publicly, he put on the face like, “I love traditional relationships, the traditional marriage,” and this sort of paradox manifests itself big time with his first wife.

Marshall Terrill: That’s true. Chris Rock had this famous saying in one of his monologues, in that, “A man is as faithful as his options.” And I try to put myself in McQueen’s shoes. If you were a guy in Hollywood at his age, with that kind of testosterone, women throwing themselves at you, it would be very, very easy to fall prey to that, but yes, he did go about. And this was kind of the thing that you did in the ’60s. You talked about… You didn’t brag about how sexy you are, you talked about your family values and how traditional you were, how this rebel has been tamed.

But behind the scenes, it was completely different, because he was at the Whisky a Go Go every night. He was friendly with the owner, Homer Valentine, and he was picking up women left and right. The Sunset Strip was his playground. But he and his wife had an understanding; he would come home at night to her, and she was accepting of that for a long time until finally, with the end of the ’60s and into the early ’70s, it just got to be too flagrant and she couldn’t stand it any longer.

Brett McKay: What was interesting, you said he would even, after a fling, he would come home and tell her like, “Yeah, I had a thing with so and so.”

Marshall Terrill: It’s hard to understand that, but yes, Neile had written about that, that was his first wife, in her book, about how that was kind of like his way of confessing and getting this sin off of his chest.

Brett McKay: What I thought was interesting, you make this point, is that he had three wives throughout his life, and you make this case that each wife, for McQueen, it was utilitarian in a way, like they served a purpose for each part of his career in his life. His first wife played an instrumental role in his rise to stardom. What was her role, do you think?

Marshall Terrill: That’s what it was. Neile represented the rise to stardom and popularity, and perhaps… Even despite what we talked about, it was a very, very steady relationship. And then, Ali MacGraw, his second wife, was almost representative of his retreat into Malibu and into his hermit phase. And then Barbara McQueen was almost like his re-emergence again. That’s kinda how I looked at things, and how I look at those marriages.

Brett McKay: McQueen, he was a philanderer, he was highly competitive, and that can be good or bad, could be petty, thin-skinned, but he was also privately… And this, again, he was very private about this. He was also very privately generous and kind. How did that manifest itself throughout his life?

Marshall Terrill: Well, he was of the belief that charity should be done anonymously, and I really respect that, and that did show itself throughout his life. He was all those things that you talked about before, but there was that other flip side to him, and that he was generous. Not only was he generous with the Boys Republic, but there were little things like, for example, on the set of Papillon, he had coconuts cut for him every morning and he’d drink the coconut milk or eat the coconut, and one day the guy that was making those coconuts sliced through his fingers with the machete, and they were basically hanging on by a thread, and McQueen had him helicoptered to Miami and made sure that his whole medical bill was taken care of.

The same thing happened to one of the writers, I think it was Mert Lawwill on Any Sunday, where he mangled his hand and he had to go in for a special operation. McQueen set it all up and paid for everything. And there was an incident in the latter part of his life where he read about a kid with cancer who probably wasn’t gonna make it past Christmas, so he arranged it to where the kid would have a limousine pick him up and taken to Disneyland and have this whole day to himself. So McQueen did do wonderful things like that that showed that he just wasn’t this jerk. There was this other side to him that was quite nice. I’ve heard just as many nice stories about Steve McQueen as I have heard bad stories, and I think that has to do with when he was in Hollywood and he was making films, he was absolutely ruthless, but when he was away from it, and he could be himself, then he was a different person.

Brett McKay: And one of I think the most touching stories is like he’d go back to the Boys Republic, and just visit, and hang out with the boys, play pool with them, just hang out and talk to them, just because. There’s this big movie star talking to these kids, and I’m sure it made their year.

Marshall Terrill: And the thing was, he wanted to show them, he wanted to give them a role model of, “Hey, I’ve been exactly where you are, and you can go on to do great things.” So he did that. He didn’t say it, but that was the reason why he did it. I think his quote was, “In life, you gotta pay back. You owe, so this is what I do.”

Brett McKay: Alright, so he had this string of hits that ended with Bullitt and he just became just a huge star. When did his star start to plummet or start to dim a bit? When do you think the moment was?

Marshall Terrill: Well, he got bigger and bigger. Now, Le Mans is interesting because it was not a box office smash or a critical hit, but it was certainly big in the European crowd, and it was, today, it’s got this life like you wouldn’t believe with all the racers. That is now the gold standard for all racing films. And then he also had another flop with Junior Bonner, but then he came back really big in ’72 with The Getaway, followed by Papillon, followed by The Towering Inferno. Now, everybody laughs at The Towering Inferno today as a disaster movie, but that disaster movie was the highest-grossing film of all time for about six months until Jaws replaced it, but Towering Inferno grossed about $300 million in 1974 dollars.

So what happened was, he got a salary of a million dollars and then profit participation I think of 7.5% of the gross, which gave him like $14 million in 1974 dollars. That’d be equivalent of like $60-75 million today. So what he did was he got burned out. I think what happened was he didn’t think that he could top himself after The Towering Inferno, and he got a little burned out, and he’d had the relationship with Ali MacGraw, and he was in the public eye for a very, very long time, so he retreated to Malibu and he didn’t do a film for a while, but he still had a film obligation, which was First Artists, which he had to deliver three films.

The first one was The Getaway, but he still hadn’t delivered the second and the third, so he took off a couple of years. That’s when his star faded a bit, but again, it wasn’t because he was in a bad film, it was because he just took himself out. He just… He could no… It’s kind of the equivalent of Michael Jordan, when he took himself out of basketball. He was too hot, and so he just took himself out. So, but the vehicle that he chose as his comeback… Well, it wasn’t really a comeback, but he had to fulfill that obligation, it was called An Enemy of the People, and it was a Henrik Ibsen play.

And McQueen had this beard and long hair and wore granny glasses, didn’t look anything like himself, and it was a play, and it was unlike anything that he had never done before, and he did it basically as an FU to the movie studio executive who kept pressing him for that obligation. So that was one obligation, and then he took off another couple of years after that, and then he came back with Tom Horn, which was 1980, and it was a flop, because it was… But that was the last of his First Artists obligation, and then The Hunter, which was billed as his big, big comeback, and then that was kind of thwarted by the fact that he was diagnosed with cancer, and then the news got out that he had cancer.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah, during the ’70s, where he took that break, it sounds like he accomplished what he wanted to accomplish, and he got to the top, and then as you said, he became a hermit. He started wearing disguises and even picking up odd jobs. He’d be like a bartender or working construction.

Marshall Terrill: That’s right. [chuckle] Yeah, he was a bartender at a place called The Old Place and all the… And it’s still around, and The Old Place is just like this funky old Western saloon, and he just… And so that’s where he went to go drink and there were sometimes like… He became friendly with all the bartenders and when they’d get busy, he’d say, “Hey, I wanna help,” and so… And he wasn’t the only movie star. I heard there were other movie stars that wanted to quit the business and just wanted to be a bartender, so that was an interesting, strange phenomenon that happened at that bar.

Brett McKay: Alright, so he kind of got burnt out from being a star, and then this is when he married Ali MacGraw. That relationship ended. And then he meets a model named Barbara Minty, who was 25 years younger than him, and what’s interesting… This is like the third phase of McQueen’s life, and he seems to really… So he had an ambitious chip on his shoulder during the ’60s, maybe early ’70s, ’70s had… He just got burnt out, kinda had a mid-life crisis, kinda became a hippie a little bit, started talking like, saying “Far out,” and things like that, and growing his beard out. And then, this last part of his life, he really started… I think kinda came to peace with himself, that he found what he was looking for since he was a kid, and a big part of that is something a lot of people don’t know about Steve McQueen, is he became a born-again Christian during this part of his life. Can you tell us about this part of Steve McQueen’s life?

Marshall Terrill: Sure. That happened with the move to Santa Paula, which is about an hour outside of LA, and that’s the antique plane capital of the world. So McQueen was a, kind of an impulsive guy, and Barbara Minty, his widow, told me, she said, “He was on the bathroom shitter when he was flipping through an airplane magazine and spotted this antique airplane that he wanted and then called, bought it.” All of a sudden, he’s flying airplanes, and then all of a sudden, he’s going to Santa Paula, driving there almost every day to fly his plane, because he wants to solo. So when he’s up there in Santa Paula, he’s being taught by a guy named Sammy Mason, and Sammy was a test pilot. He was a World War II guy, about 10 years older than Steve, and Steve was looking for a father figure all of his life because his father obviously… He never knew his dad and his father walked when he was six months old.

And so, Sammy had this thing about him, this presence about him that Steve couldn’t quite put his finger on, so one day Steve said, “What’s different about you, I can’t quite put my finger on you,” and that’s when Sammy said, “Well, Steve, I’m a born-again Christian.” And so, from that point on, Steve tried to emulate Sammy and he started asking him, “Hey, can I go to church with you, can I sit with you?” So something had obviously taken hold. And then I spoke to the pastor of that church who said one day after three… He had heard about Steve McQueen attending, but he made it a point, and he made it a point of telling his congregation, “Do not bug this man.” He said, “One day, three months after he started attending, I got this tap on my shoulder and it’s Steve, and he asked me to go to lunch.”

And so Steve, they went to lunch, and he said that Steve grilled him for about two hours on the Christian faith and the Christian walk, and he answered all his questions, and when Steve was finished, he smiled and said, “Okay, well, that answers about all I have,” and so, the pastor… His name’s Leonard Dewitt, he said, “Well, Steve, I only have one question for you,” and Steve smiled and said, “You wanna know if I’m a born-again Christian, don’t you?” And he said, “Yes, that’s all that really matters to me.” And Steve said, “Well, do you remember a couple weeks ago when you had that invitation to accept Christ into our hearts and say a prayer?” And he goes, “Yes.” He goes, “Well, I did that.”

And so people noticed that there was a change in him. His widow said, “One day, Steve just said, we’re going to church, let’s go get you some dresses,” ’cause he didn’t want her… He was kind of old-fashioned in a lot of ways, he wanted her to wear a dowdy dress that went below her knees, and then they had Bible study lessons, because they were gonna get married, and they were gonna learn how to become a Christian couple. So these were things that Steve was doing at the end of his life, and this was before he had the cancer. A lot of people like to peg it to, “Oh, he had cancer, so he knew he was dying, and he’s preparing herself.” That wasn’t the case. He was going to the church in the spring of ’79 and he was diagnosed with cancer in December of ’79, so that disproves that.

Brett McKay: And then people also said that, the people you interviewed, that his, I don’t know, his demeanor changed, like he became less volatile and just… I don’t know, less mean. He just kinda mellowed out after this happened.

Marshall Terrill: That’s true. And again, he continued on with doing nice things. On the set of The Hunter, his stuntman Loren Janes said that he saw these kids tossing a football around, and it was this football laced with wire, stuffed with rags, and that he looked at Loren and Loren knew that as a cue to… He gave Loren $300 bucks and so Loren went out and bought all these footballs, baseballs, baseball bats, lined them up in the field one day, and then the kids just went at it. And then, there was also another case where he learned of this young lady by the name of Karen Wilson, who came to the movie… Who came to the set every day, and he said, “Why aren’t you in school?” And she was telling him about, well, her life, that her mother was an addict and that she was dying and that she needed the money. And Steve and Barbara pretty much adopted this young lady, and I’m in touch with her to this day, and Karen is in the banking industry and she often credits Steve with saving her life.

So these are the unknown stories, the nice stories of Steve McQueen. So those were the things that he did as he got older and mellowed out. And Bud Ekins, his best friend, just said, “He just became a nicer human being.”

Brett McKay: So you mentioned… He got mesothelioma because of that stint he did in the brig and it finally manifested itself in the late ’70s, and this is when he starts dying, this is the final act of Steve McQueen, and it’s really… It was so sad. I was like, man, I was rooting for… I was hoping he’d make it through, even though I know the end of the story. And what made his death even sadder was how public it was, the first time a celebrity’s death was incredibly public, which made it even more unpleasant. Can you tell us about the end of Steve McQueen’s life?

Marshall Terrill: Well, yes, and specifically, in regard to the gossip rags, I think at that time, and I write this in that book, that the National Enquirer was taken over by a new editor who had new ethics, and he felt that Steve McQueen was a public figure, people would want to know about him, and I think they… A nurse who had his medical records, Steve’s medical records, tipped off the National Enquirer and they wrote a story about it. And so from that point on, there was kind of a death watch on Steve McQueen, and I can’t think of another celebrity where that happened, where they would just watch this person. And then, put out bounties, there was a bounty on Steve for $50,000, to get a picture of him in his cancer-riddled state.

And when he passed away, there was a really ugly incident where the media came in and took pictures of his body in the morgue, and that was the Mexican media, and there was one member of… And I actually talked to him and I asked him why he did that. Because this guy told me that McQueen was his hero, and he said, “I was a young reporter, and was told to do my job and if I didn’t come back with that roll of film, I’d be fired.” So that’s how things got. Now, today, I think that still exists to some certain extent, but at that point, that was the start of that, and that’s where perhaps, was its ugliest.

Brett McKay: What was also sad about his death was McQueen was… At times, the way… The vibe that I got was that… Vibe, he liked to use that word, vibe, McQueen did. Was that… He was at peace, both at peace with his… That he was dying, but also, really desperate to keep living. In fact, he did these really controversial cancer treatments down in Mexico, ’cause he really thought it would work and he could get out of this.

Marshall Terrill: Yeah, and he flip-flopped between if he was gonna live or die, and the main reason why he kept going was for his kids, he wanted to live for his kids. You certainly can’t blame a guy for wanting to do that. It was just very sad, but he was such a strong guy that it was hard for everybody to comprehend that he had cancer. That’s what made the story even more compelling was this macho action star has cancer and he’s ailing, and we should probably document it. That was… Again, that was the attitude at that time.

Brett McKay: You’ve spent a better part of almost 40 years writing about Steve McQueen and talking to the people that knew him. What’s your… What are some of the big takeaways from Steve McQueen? How has he influenced… Has he changed your life, or you’ve done things, you’ve emulated things about Steve McQueen, what’s your takeaway as a biographer?

Marshall Terrill: Well, I can say that he’s influenced my life in terms of my career. I wouldn’t have a literary career without Steve McQueen. In terms of emulating him, I’d have to say no. What I would try to do or learn the lessons of his life, but he was a guy that pulled himself up by the bootstraps. Back then, America’s economy wasn’t such that you had many choices, especially for somebody who had a ninth grade education, so here was a guy that had a terrible background, didn’t have many choices economically, but worked hard, and once he got into acting, he worked incredibly hard and then became this mega star.

It’s proof that the American Dream still exists. So that’s kind of the takeaways that I have for him, is that, in a way, he’s the embodiment of an American Dream, but in his personal life, certainly was not. But he showed that you could come from any circumstance and become very successful. In terms of, will there be another actor like Steve McQueen, that’s like saying will there be another John Wayne, will there be another Beatles, will there be another Bruce Lee. And the answer is no. Will there be another Elvis Presley? No, because they broke the mold… I call them, they’re icons who are iconoclasts. They broke the mold, and nobody should even try to emulate them or try to be like them. They need to be their own person and have their own identity.

Brett McKay: Well, Marshall, this has been a great conversation. Is there some place people can go to learn more about your work and your latest book too, about Steve McQueen?

Marshall Terrill: Well, the latest book is called Steve McQueen In His Own Words, and you can get that at www.daltonwatson.com. As far as my work, the best place to go is to go on amazon.com, and you’ll see all the variety of books that I’ve written.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Marshall Terrill, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Marshall Terrill: Well, thank you so much, I enjoyed it.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Marshall Terrill. He’s the author of multiple McQueen biographies. His latest is Steve McQueen In His Own Words. They’re all available on amazon.com, also check out our show notes at aom.is/McQueen, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM Podcast, and wraps up another year of podcast, putting out two podcasts week after week for 52 weeks out of the year isn’t just me, it’s a team effort, so I wanna take this time to thank those involved in making the Art of Manliness Podcast happen. First off, we have Kay McKay, our Podcast Editor, she listens to each episode over and over again, makes cuts, makes sure things flow right, it’s snappy. So thank you, Kay, for all the work you do.

We also have Jeremy Anderberg, our Podcast Producer, he just oversees the whole podcast process, he lines up our guests, he makes sure guests has mics, he does sound checks with guests, uploads the podcasts, makes sure everything goes out on time, he just oversees the process. So thank you, Jeremy, for doing that.

We also have Creative Audio Lab, they’re our sound engineers based out of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. We give them the podcast, they clean it up, make sure it sounds the best that we can. So thank you to them.

And finally, thank you to all who listen to AOM Podcast. Your support is what makes this happen. Thank you for listening, thank you for sharing, we’re looking forward to another year, 2021, of Art of Manliness Podcast. So until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you not only listen to the AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.