One of the things that makes the James Bond books better than the James Bond films, is that while the latter mostly represent not-too-deep action-driven entertainment, the former are peppered with philosophical asides. Ian Fleming’s 007 has arguments with his nemeses on the nature of power and autonomy and discussions with colleagues as to how one can know if they’re really on the right side of things.

Bond himself lives with a certain personal philosophy, one that mixes different elements, including Epicureanism and existentialism. Its strongest streak, however, is that of Stoicism. Which certainly makes sense: the life of a secret agent is full of uncertainties. Bond is never sure what to expect on his missions and must deal with a constantly changing landscape — both physically, in terms of unexpected dangers and obstacles, and psychologically, in the form of feeling out new rivals and colleagues and dealing with double-crossings. He is invariably captured by his enemies and must endure merciless torture without cracking under the pressure. And, of course, he is constantly faced with the prospect of death — the very real chance that he will not come through his next mission alive.

While the fictional Bond must grapple with unusually acute pressures, the Stoicism he adopts in response to them has something to teach all of us in our more ordinary real-world operations.

Concentrate on What You Can Control — Secure Your Base

Life’s variables can broadly be broken down into things over which we have control, and things over which we do not.

When it comes to the former category, Bond has his hand on the tiller of details and stacks each of them in his favor. As Fleming writes in Moonraker: “Whenever he had a job of work to do he would take infinite pains beforehand and leave as little as possible to chance.”

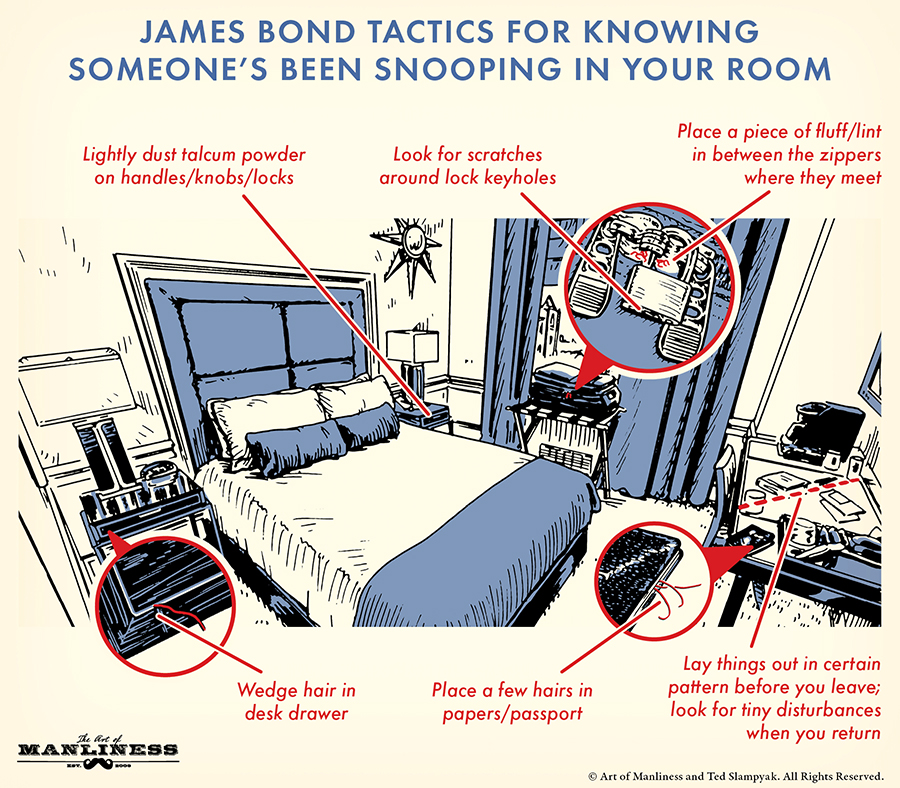

Bond ever looks to achieve “Clausewitz’s first principle” by making “his base secure.” Securing his base creates a personal “headquarters” that is well-defended against external disruptions. For Bond this means finding out as much information about the people and places in a case as possible, partnering with competent allies, making sure his equipment is in working order (e.g., repeatedly assembling and reassembling his gun), vigorously training in the specific skills which an operation will require (as well as learning a variety of other arts just in case they’re needed), and mentally visualizing beforehand exactly what moves he’ll make.

By planning and executing every controllable element to a T, Bond ensures he’s always operating from a position of greatest possible strength. As his antagonist in Dr. No explains, echoing 007’s own philosophy: “Mister Bond, power is sovereignty. Clausewitz’s first principle was to have a secure base. From there one proceeds to freedom of action.”

Accept What You Cannot Control — Including Your Own Death

Once “There was nothing else he could do or insure against,” Bond would relax, accepting that “The rest was up to the Fates.”

Bond understands that no matter how much you magnify your individual agency, it’s impossible to plan for every exigency, nor influence every variable. He balances supreme confidence with realistic humility. At the same time, he understands that there is still an element of autonomy in dealing with the unforeseen and uncontrollable: the decision to accept unalterable circumstances instead of letting them disrupt one’s equilibrium.

Bond has a healthy understanding of the power of Fate, including as it concerns death. He accepts the inevitability of his own, and the fact that an untimely demise is always a possibility — not just because of the nature of his precarious profession, but the unpredictability of life in general.

The ironic thing about Bond, is that while he can cooly face maniacal enemies who cruelly torture him before attempting to kill him . . . flying on a commercial airliner causes him to sweat. This is in some ways understandable, however; no matter how far an adversary pushes him into a corner, Bond always feels there are things he can do to fight back; but as a passenger on a plane, he is utterly powerless to influence his fate.

In Live and Let Die, Bond finds himself en route to the Caribbean, aboard a plane buffeted by a storm. As the aircraft shudders and shakes, rain slashes against the windows, and dinner dishes crash to the floor (this was a more luxurious time to fly), he tightly grips the arms of his chair as he tries to come to grips with riding a fate that is out of his hands:

He looked at the racks of magazines and thought: they won’t help much when the steel tires at fifteen thousand feet, nor will the eau-de-cologne in the washroom, nor the personalized meals, the free razor, the ‘orchid for your lady’ now trembling in the ice-box. Least of all the safety-belts and the life-jackets with the whistle that the steward demonstrates will really blow, nor the cute little rescue-lamp that glows red.

No, when the stresses are too great for the tired metal, when the ground mechanic who checks the de-icing equipment is crossed in love and skimps his job, way back in London, Idlewild, Gander, Montreal; when those or many things happen, then the little warm room with propellers in front falls straight down out of the sky into the sea or on to the land, heavier than air, fallible, vain. And the forty little heavier-than-air people, fallible within the plane’s fallibility, vain within its larger vanity, fall down with it and make little holes in the land or little splashes in the sea. Which is anyway their destiny, so why worry? You are linked to the ground mechanic’s careless fingers in Nassau just as you are linked to the weak head of the little man in the family saloon who mistakes the red light for the green and meets you head-on, for the first and last time, as you are motoring quietly home from some private sin. There’s nothing to do about it. You start to die the moment you are born. The whole of life is cutting through the pack with death. So take it easy. Light a cigarette and be grateful you are still alive as you suck the smoke deep into your lungs. Your stars have already let you come quite a long way since you left your mother’s womb and whimpered at the cold air of the world. Perhaps they’ll even let you get to Jamaica tonight. . . .

There, we’re out of it already. It was just to remind you that being quick with a gun doesn’t mean you’re really tough. Just don’t forget it. This happy landing at Palisadoes Airport comes to you by courtesy of your stars. Better thank them.

When Bond takes another turbulent flight in From Russia With Love, we learn more about how he deals with his fear of flying, and with life’s uncontrollable vicissitudes in general:

In the center of Bond was a hurricane-room, the kind of citadel found in old-fashioned houses in the tropics. These rooms are small, strongly built cells in the heart of the house, in the middle of the ground floor and sometimes dug down into its foundations. To this cell the owner and his family retire if the storm threatens to destroy the house, and they stay there until the danger is past. Bond went to his hurricane-room only when the situation was beyond his control and no other possible action could be taken. Now he retired to this citadel, closed his mind to the hell of noise and violent movement, and focused on a single stitch in the back of the seat in front of him, waiting with slackened nerves for whatever fate had decided for B.E.A. Flight No. 130.

Focus on the Present — Take Things One Step at a Time

Another way Bond maintains his equilibrium is by concentrating on the present instead of regretting the past or worrying about the future: agonizing over “What-might-have-been was a waste of time”; fretting about what-might-be was “a dividend paid to disaster before it is due.”

Bond feels particularly strongly about the uselessness of the former mindset. “Never job backwards,” he held, for “Regret was unprofessional–worse, it was death-watch beetle in the soul.” Bond not only approached his work this way, but even his pastimes. In a game of golf, for example, he “never worried too long about his bad or stupid shots. He put them behind him and thought of the next.” He brought the same approach to gambling, in the knowledge that “The cards have no memory!” That is, the fact that your last hand was a disaster has no bearing on the cards you’ll be dealt next. Instead of ruminating on what is done, you play each hand as it comes.

Bond’s commitment to focusing on the present comes most vividly into focus when he finds himself trapped in a sort of obstacle course set up by Dr. No — a sadistic gauntlet which in part forces him to crawl through a body-battering, tarantula-filled, sometimes super-heated air duct. At times, Bond isn’t sure he can continue, but he reminds himself that he can “either go back [and die], or stay where he was [and die], or go on. There was no other decision to make, no other shift or excuse.”

The only way out is forward, and Bond wills himself to keep moving by “refus[ing] to look up to see how much more there was.” Knowing that looking ahead “might be too much to bear,” he tries to think of nothing else but what is immediately in front of him:

Don’t worry about losing your grip and falling to smash your ankles at the bottom of the shaft. Don’t worry about cramp. Don’t worry about your screaming muscles or the swelling bruises on your shoulders and the sides of your feet. Just take the silver inches as they come, one by one and, and conquer them.

Don’t Let Hardness Become Petrification — Always Seize the Initiative

The danger of Stoicism is that it can devolve into an overly defensive posture. You accept things as fate that are actually within your control. You spend so much time retreating to your inner citadel that you begin to rot away inside it. You become so indifferent to what happens to you, so emotionally apathetic, that you harden yourself into a dumb, immobile stone.

Bond successfully leavens his Stoicism with an unquenchable penchant for action and initiative. The strength of his emotional fortifications never become a rationale for failing to take the offensive.

For Bond, even when making a move isn’t practically useful, it’s still psychologically crucial. For example, in Live and Let Die, he and his partner try to break free from the bad guys’ restraints, even though he knows little will be gained in the attempt — and indeed, all the agents receive in return for their resistance is a beat down. Yet Bond still considers the action worthwhile: “It had been a futile effort, but for a split second they had regained the initiative and effaced the sudden shock of capture.”

The feeling of momentum is crucial to 007. As he reflects in Dr. No, “It was the mistakes one made at the beginning of a case that were the worst. They were the irretrievable ones, the ones that got you off on the wrong foot, that gave the enemy the first game.” You wanted to strike first, to get the upper hand from the get-go, and this was as true in work as in pursuits of pleasure; during a game of golf he “remembered the dictum of the pros: ‘It’s never too early to start winning.’ ‘It was always too early to start losing.’”

Bond’s abhorrence for stagnation serves as an overarching principle for his entire life. He knows that stagnation leads to deterioration, that idleness kills manliness — that “Those whom the Gods wish to destroy, they first make bored.”

Bond is only given an assignment two or three times a year. “For the rest of the year he had the duties of an easy-going senior civil servant.” When not on a mission, he goes over paperwork at the office, plays cards with friends and woos local love interests in the evening, and golfs on the weekend. But after “months of idleness and disuse,” this kind of pedestrian 9-5 lifestyle eventually brings him to a psychological breaking point; he begins to feel like a “surly caged tiger.”

Such is the situation we find our secret agent in in From Russia With Love:

The blubbery arms of the soft life had Bond round the neck and they were slowly strangling him. He was a man of war and when, for a long period, there was no war, his spirit went into a decline.

In his particular line of business, peace had reigned for nearly a year. And peace was killing him.

After “grinding away at the old routines,” his mind is becoming less sharp, his mood increasingly downcast; “the sword was rusty in the scabbard.” Yet rather than entirely giving in to this funk, he finds small ways to push back against it, beginning with his morning routine (which includes, what else — a James Bond shower):

At 7:30 on the morning of Thursday, August 12th, Bond awoke in his comfortable flat in the plane-tree’d square off King’s Road and was disgusted to find that he was thoroughly bored with the prospect of the day ahead. Just as, in at least one religion, accidie is the first of the cardinal sins, so boredom, and particularly the incredible circumstances of waking up bored, was the only vice Bond utterly condemned . . .

There was only one way to deal with boredom–kick oneself out of it. Bond went down on his hands and did twenty slow press-ups, lingering over each one so that his muscles had no rest. When his arms could stand the pain no longer he rolled over on his back and, with his hands at his sides, did the straight leg-lift until his stomach muscles screamed. He got to his feet and, after touching his toes twenty times, went over to arm and chest exercises combined with deep breathing until he was dizzy. Panting with the exertion, he went into the big white-tiled bathroom and stood in the glass shower cabinet under very hot and then cold hissing water for five minutes.

At last, after shaving and putting on a sleeveless dark blue Sea Island cotton shirt and navy blue tropical worsted trousers, he slipped his bare feet into black leather sandals and went through the bedroom into the long, big-windowed sitting-room with the satisfaction of having sweated his boredom, at any rate for the time being, out of his body.

For Bond, who had endured many a physical pummeling, boredom was yet “the worst torture of all.” So he stoically accepted fate, he indifferently acceded the inevitability of death, but he always held that avoiding a life of quiet desperation was firmly within his control.

Want to try reading Fleming’s Bond books but aren’t sure where to start? Here are the 5 best.