It’s a common trope that adult men don’t value friendship as much as their female counterparts, and that men really don’t need or want friends like women do. But my guest today argues that assumption is wrong and comes from viewing friendship from a strictly female point of view. In fact, based on his research, most adult men very much want good friends but just don’t know how to make them. What’s more, he says, male friendships look different from female ones and we should stop judging the quality of male friendships based on how women do them.

My guest’s name is Geoffrey Greif, and he’s a sociologist and author of the book Buddy System: Understanding Male Friendships.

Today on the show, Geoffrey shares the common myths about male friendships, the benefits men get from having friends, and how male friendships are different from female friendships. He then discusses the four types of friends a man will have in his life, how friendship changes as men age, and how fathers have a huge influence on whether their sons will have friends as adults. Geoffrey then shares his research on how couples navigate friendships together and why some brothers are best friends, while others don’t talk to each other for years.

Show Highlights

- How Geoffrey got started studying friendship, and particularly, male friendship

- The most common myths about male friendship

- The difference between male friendships and female friendships

- The side-by-side nature of male friendships

- 4 categories of friends men have

- Why people today are lonelier than ever before

- How many friends does someone really need?

- How male friendship has changed over the decades

- The ways in which a father’s friendships impact those of the son(s)

- How a father’s sibling relationships carry down to the friendships of the son(s)

- How do friendships change as a man ages?

- Why men sometimes rely on the spouse for their social life, and why making couple friends is hard

- Why the busy man in his 30s and 40s should be intentional about spending time with friends

- So how do men actually go about making friends in adulthood?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Podcast: Building Your Band of Brothers

- Bosom Buddies: A Photo History of Male Affection

- On the Importance of Keeping in Touch With Old Friends

- The Joys and Difficulties of Making Friends in Adulthood

- How to Build Relationships That Don’t Scale

- Making and Keeping Man Friendships

- The History and Nature of Man Friendships

- 5 Types of Friends Every Man Should Have

- Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

- Love Is All You Need

- Podcast: The Importance of Fathers

- The Ultimate List of Hobbies for Men

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Harry’s. Upgrade your shave with Harry’s. Get a free trial (you just pay shipping) when you go to harrys.com/manliness. The trial includes a razor handle, 5 blades, and shaving gel. Visit today and take advantage of this exclusive offer!

Squarespace. Get a website up and running in no time flat. Start your free trial today at Squarespace.com and enter code “manliness” at checkout to get 10% off your first purchase.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. It’s a common trope that adult men don’t value friendship as much as their female counterparts, and that men really don’t need or want friends like women do, but my guest today argues that, that assumption is wrong and comes from viewing friendship from a strictly female point of view. In fact, based on his research most adult men very much want good friends, but just don’t know how to make them. What’s more, he says male friendships look different from female ones, and we should stop judging the quality of male friendships based on how women do relationships. My guest’s name is Geoffrey Greif. He’s a professor of sociology at University of Maryland, and he’s the author of the book, Buddy System, understanding male friendships.

Today on the show, Geoffrey shares the common myths about male friendships, the benefits men get from having friends, and how male friendships are different from female friendships. He then discusses the four types of friends a man will have in his life, how friendship changes as men age, and how fathers have a huge influence on both their sons and daughters, and whether they’ll have friends as adults. Geoffrey then shares his research on how couples navigate friendships together, and why some brothers are best friends while others won’t talk to each other for years, even though there’s no grudge there at all. Really fascinating show. After the show is over, check out our show notes at AOM.is/buddysystem, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic. Geoffrey Greif, welcome to the show.

Geoffrey Greif: Thank you very much, Brett.

Brett McKay: You wrote a book highlighting research you did on male friendships, called The Buddy System. Curious, before we get into the details about the book, what led you down that path to research friendship, but particularly male friendship?

Geoffrey Greif: Since my masters program in the early 70s, I’ve always been interested in men in non-traditional roles. I did my dissertation a few years later on single fathers raising their children alone after divorce. I followed that up with another book on the same topic, and a book on mothers without custody. That’s how I became interested in the topic. I was a father who was very engaged, and I’ve always been married to the same women, very engaged in raising his children. I’ve had an interest in men in non-traditional roles, men’s consciousness raising groups in the early 70s. It was a natural path to follow to look at men and fathers, and then as I did a bunch of other research, I came back to the notion of, “What about men and their male friendships? How do men handle a range of roles in which they are placed?” The genesis was maybe 25 years before I actually did the final work on this.

Brett McKay: As you highlight in the book, there are a lot of myths about male friendships. What are the most common ones that you’ve found in your research?

Geoffrey Greif: I think the most common myth around men’s friendships is that they are not as important to men as women’s friendships are to women. What I try to describe in the book is that this is a relationship that is highly important to many men, it just does not look like what women’s friendship might look like. Women tend to have friendships that are more emotionally and physically expressive than do men. Men’s friendships tend to be, on the other side of this, of course, less emotionally and physically expressive. When a man might go and watch the football game at his friend’s house and come back home, his wife or partner will say, wife might say, “Did you know that Bill was breaking up?” And the man might say, “It never came up.” She might say, “What kind of a friendship is that?”

A lot of men don’t necessarily want friendships where they have to open up emotionally a great deal. That does not mean the friendship is not incredibly important. You think of the men in war who share a foxhole with each other, and then 25 years later, one combatant will call the other former combatant and say, “Can you come and help me?” Either friend would drop everything they’re doing, no questions asked, and go and help the other guy without necessarily needing to talk about it. I think it’s a matter of, men tend to be, in general, and they tend to construct their friendships differently than women, but they tend to be in general less physically and emotionally expressive, but it does not mean that their male friendships are not incredibly important to them.

Brett McKay: Why do you think, like the female type of friendship is sort of held up as the ideal? Because of that, men’s friendships are seen as defective.

Geoffrey Greif: I think that women, because they are greater experts of communication are able to communicate that this is an important part of their lives, and also a lot of men do open up to women more than they open up to men. It’s been said that if you ask a lot of husbands who their best friend is, they will say it’s their wife, whereas you ask that same question of the wives, they will often mention other women, not their husband. In part because men have not been trained to the extent that I wish we had been trained to be good listeners and to be good processors. Again, I want to frame this as it doesn’t mean that men’s friendships are less than, or it’s a deficit model of friendship. It’s just that we’re interested in different things and different relationships than are women.

Brett McKay: Another difference you highlight between the male and female friendship is men’s friendships tend to be side by side, and women’s tends to be facing each other. What do you mean by that?

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah, yeah. In the book we talk about, I talk about this being a shoulder-to-shoulder relationship. Men like to get together and do things with other people. We can say that’s a throwback to the early years, the cavemen years where we had to go out in groups and hunt, or we had to go out and defend the homestead, the fields, the cave, whatever it is that was being defended, and we had to travel that way, shoulder-to-shoulder. We got accustomed to going out in shoulder-to-shoulder ways, and we still feel more comfortable relating to each other.

Men tend to call up their friends and say, “Let’s go out and do something. Let’s go play sports. Let’s go to the bar and watch sports. Come to my house and we’ll watch sports.” Women tend to feel more comfortable, and going back to the cave women, while the men were out, the women in the beginning of the neolithic age, would go and be working together in tandem, maybe tending the crops, maybe taking care of children, maybe preparing of food, they were doing much more face-to-face activities. Women today still feel more comfortable having an intimate, face-to-face discussion with another woman. It’s rare you’ll hear men say, “Let’s get together and have a glass of wine at this great, new, intimate French restaurant that just opened up.” Men, I think, in general would not feel as comfortable talking about that and going to that kind of an event as women.

Brett McKay: In your book, it’s called The Buddy System, and it’s this system of categorization of friends that men have. Can you walk us through these four types of friends that men have, and where do you see most men like … Where do they get most of their friendship at?

Geoffrey Greif: Good question. I was able to, after reading through the qualitative interviews, the survey data to come up with four different categories, and to make them easier to remember, maybe for only me, I rhymed them. The most intimate are your ‘must’ friends. These are people that you must call if something catastrophically bad or catastrophically good happens, if you lose a family member or you win the lottery. Who are the first two, three, or four men that you’re going to call? These are your closest, your must friends. That’s a pretty small category.

There is a second, wider category called ‘trust’ friends. These are guys that I might see at parties, I might run into them in the store, or at some event, and I love talking to them. I trust them. I feel we have something good going, but we’re often traveling in different circles, and are not going to necessarily find a lot of time to get together, and maybe they don’t have quite that level of intimacy with me, but I can still trust them and feel very connected to them. That’s a nice sized category.

You get into a larger category of people that are just friends. Those are acquaintances, people you know at work, people maybe you go out to lunch with. They may know about your life, they may not know about your life. They are certainly not going to know about your most personal details, should you choose to share those with your must or your trust friends, but they’re still people that you hang with from time to time, though maybe not in a planful way, maybe more spontaneously.

Then, there are your rust friends. Those that are friends from way back. A lot of people have friends that they made in high school, college, early jobs that they really haven’t kept up with, but every time an alumni event comes up, your 30th, your 40th, your 50th, you go back and see these people again and you are taken back to the time when maybe you were very close with them, but your lives have settled in different parts of the country, or in different professions, or in different political interests. Your rust friends can be your must friends. A lot of men hold on to friends from high school and say, “These are the most important friends I have because I need to have known somebody for a long time to really consider them a friend.” There can be overlaps between the rust and the must friend, or the trust friend. It’s just a way of my trying to categorize friendships and saying, “Well, wait a minute, there’s a way of thinking about these.”

Brett McKay: Do women have these same type of four friends, or is it just … You see this more in men?

Geoffrey Greif: You know, I’ve never been asked that question before. I did interview 120 women for the book and compared some of their responses to some of the men’s. I would say there is a great similarity between the two, and I think these do work across gender.

Brett McKay: Where do you see most men, what category of friends do most men have?

Geoffrey Greif: When you ask men, and we ask them specifically, “Do you have enough friends?” A fair minority said, “no, I wish I had more friends.” There were men that did say that they have enough, sometimes that can be two, three, or four friends. I want to say that there was at least one or two men who said, “I only have one good friend and that’s all I need.” I want to get away from the notion that one has to have a lot of friends in order to be a good person or have strong friendships. If somebody says, “All I need is one friend to sustain myself.” I’m going to take that person at his word.

It does get into some of what the Greek philosopher Aristotle said about the number of friends. He wrote a great deal in Nicomachean Ethics about friendships. One of his key points is that friendship is such a wonderful state of affairs and should be held in such high esteem that one really can’t have too many friends, because a true friendship takes so much out of one. When we get into the number of friends, I think it’s hard to really classify these things. We do know, in the data, not mine, but others, public health data support the obvious, that people with large social networks, people with friendships live longer, happier, healthier lives.

Of course that makes sense. You get more social stimulation from people, and you also may learn more things. I may see a friend who says, “You don’t look very good. Have you been going to the doctor?” That may be the kind of encounter that would push me to finally go and see the doctor to realize that I need to do something about an issue that I have. I know we’ve morphed from the discussion about the categories into the number, and now into Aristotle, but I think it’s important to sort of look at this from a perspective of, where do friendships sit in our life, and what are we trying to accomplish, and what do we gain from them.

Brett McKay: Right. You highlighted the research saying that friendship provides all these amazing benefits in terms of health. There’s also all these reports that men today are lonelier than ever. Not just men, but it’s like people in general are lonelier than ever, particularly men, because maybe they’re just not adept at making friends. Since you’ve done this research, have you been following up and seeing how things have changed in terms of the number of friends people have or how important friendship is?

Geoffrey Greif: I think it’s conflated a lot with, and the Pew Research Center does a fair amount of research on contacts and friendships through media, like Facebook. Do I have more friends now because I can track people down and see how they’re doing? Am I less isolated now because I can decide to track somebody down and send them a quick post? Whereas before it would have required me to find their name in the phone book some place. I don’t know how that is sitting in terms of greater ease of contact, but does that equal less meaningful contact? I think it’s a really difficult thing to determine if men and women are more lonely than they are today.

I think certainly men are more open, they are more emotionally and physically expressive. Younger men are more openly expressive than were their fathers, and their grandfathers. I think that can, in fact, bode well for people. We’re much more accepting of people that are different than ourselves, especially in relations to gays and lesbians. They are much more accepted. If gay men are more accepted, it makes straight men not feel as uptight about being emotionally expressive as their fathers or grandfathers would have been.

Brett McKay: That’s an interesting point. We’ve done a lot of writing and research about the history of male friendship. One thing I was surprised about and struck by, if you go back to the 19th century, or the 18th century, even the Ancient Greeks, the male friendships then were very emotive, and they were very expressive. You see these letters from the founding fathers to each other and they’re just like, “You’re so dear to me, and I love you, and I wish I could be next to you.” The sociologists who had done this stuff, they said, “Well, the reason why they were able to do that is because there wasn’t … Like homosexuality or gay didn’t really exist, like the idea of it as an identity didn’t exist.” They weren’t worried about that, but as that change happened in the late 19th early 20th century, that’s when men became, “Okay, I can’t be that because I don’t want people to think I’m gay.”

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah, of course I write about that in the book, but borrowing the research of other people, the other historical research, and I didn’t know that the term homosexual didn’t exist until the end of the 19th century. I’m citing someone else’s work on that, because I haven’t looked at the primary source material, but I concluded from what I read at that point was that somehow the role of straight and strong man came under fire as more African-Americans and more women entered the workforce, men’s privileged role, white men’s privileged role, and we still have a great deal of privilege now being white men, I believe. Came under pressure, so people tried to distance themselves. You used to see young boys, two and three year olds with bowl haircuts and long hair. At some point, that became not something that mothers or fathers wanted their children to be photographed as, or painted as. There was a push away in an attempt to be more masculine. I think that’s when men started to separate themselves more emotionally, and to be a little more concerned with how they came across each other and to society.

You know, the image of the lover is two fold from 400-500 years ago, you were the poet. The man with the golden tongue who could woo a woman by standing outside her window and reciting poetry. On the one hand, but there was also the knight in shining armor on the other hand. It’s an interesting balance between the two. One could be masculine and be a great poet, silver-tongued, or one could be masculine and be the strongest, best knight on the playing field.

Brett McKay: Yeah, they had a much more, I guess broader idea. They kind of encapsulated the brains and the brawn. We seem to be very monolithic today. Let’s get into the chapter I thought was really interesting, and I never really though about, in terms of my friendships, is when you interviewed the men you talked to about how their father’s friendships influenced their ideas of friendship. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah. It’s not a real surprise that borrowing from the family therapist Murray Bowen who wrote a great deal about the inter-generational transmission of values and what we learn from our fathers and grandfathers. Obviously we stand on the shoulders of those that came before us. I think it’s important to think about that we clearly learn a lot from our mothers and our fathers. We found that people learned about friendships from their fathers about what kind of friends did my father keep, and what are the implications of that for me. There are usually three ways to go with this. Either you follow in the same pattern as your father.

You take the exact opposite approach, or your father’s patterns have no influence on you. A lot of the men that I work with now, and I had been running groups for fathers in prison, we talk about what message did you get from your father. A lot of these guys did not have fathers in their lives. They swore to themselves before they got into prison, “I’m not going to abandon my children the way that my father abandoned me.” And they feel guilty about not being there anymore for their children after their father was not there for them. We, of course, encourage in the group that they stay involved. Even though they are physically absent, they can still be emotionally present. What we learn from our fathers and from our mothers is incredibly important and can guide a lot of what we do.

In a more recent book I have out on adult sibling relationships, we found interestingly enough that in these interviews with people 40 to 90, if you believed his father was close with his siblings, you were more apt to be close with your siblings. Whereas, mothers closeness with her siblings, which is much more common than fathers being close with their siblings is not a predictor of closeness with your own siblings. If you grow up and see your father very engaged with his brothers and sisters, it’s going to encourage you to be engaged with your own siblings. That’s an important part of public health also. In general, this is under the while mantle of the importance of what we learn from our parents. In this case, we’re look at dads.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s amazing. Sometimes we under estimate the power of a father. We had a guest on a while back ago highlighting the research. He saw something similar where the father had more of an influence on the children than the mother did. It was like, if there was a father in the … Like the children tracked their father’s BMI. If the father was overweight, but the mother was not, the children were more likely to be overweight, but if the mother was overweight but the dad wasn’t, then the children weren’t going to be overweight.

Geoffrey Greif: Interesting, I didn’t know that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the mother had no influence on it, but the dad did.

Geoffrey Greif: Right, interesting.

Brett McKay: Going back, because I like this idea of sibling relationships. The dad has a big influence, but are there any other factors that contribute to … I know some siblings, particularly brothers who are like, they would say their best friend is their brother. There are some siblings, their brother is just some person. Like after they leave the house, they really don’t have much to do with each other. Not that they don’t love each other, care about each other, but they wouldn’t say these are best friends. Besides the dad, are there any other differences you found there in your research?

Geoffrey Greif: In terms of the sibling findings?

Brett McKay: Yeah, the siblings. Why are some siblings best friends, why some brothers are best friends and-

Geoffrey Greif: There are brothers that are best friends. That was a minority of those we talked to. It’s such a complicated relationship with you sibling, if you’re talking about two brothers, there’s often a great deal of competition with them. There are 10 million interactions you have with your siblings as you’re growing up. Your siblings, rather than men’s friendships and women’s friendships are in most cases the longest relationship you’re ever going to have, longer than with your friends, unless you become a friend at a very young age before another sibling is born. Longer than your relationship with your partner, and your parents, and with your children.

The notion of trying to get through childhood and then into adulthood and staying close with somebody is very difficult. I can drop a friend if I don’t like him. If he does something I think is beyond repair for our relationship. It’s harder to drop a sibling because they are always a shadow in your life, whether or not you’re close with them or emotionally cut off from them and have no contact with them. In comparing men’s and women’s or brother’s and sister’s relationships, sisters, like women, tend to play a more central role, we found, in navigating these relationships. They tended to be the conduit.

They tended to feel more comfortable talking to each other than did brothers, though the younger brothers in the 40 to 55 range looked pretty comfortable too, and had a comparable level of comfort in talking about important matters with their siblings, as did all of the women. It was the older men, the 55 to 85 or 90 group of brothers that tended to have the least amount of communication. Having a brother with whom one is close and is a best friend, that I’m very, very close with my brother, is to some extent based sometimes on what our parents did, on what the sibling’s parents did. We found that if there’s more perceived interference from a parent when siblings are young, that means siblings are not going to be as close to each other. Interference is essentially cross-culturally looked at from the speaker’s point of view.

Everybody knows what interference is, but what interference in some culture might look from the outside is different from what it might look like in another culture. That’s different from a parent intervening to protect one child from the other, or stepping in and saying, “Look, stop beating up your younger brother.” It’s more the sense that a parent incorrectly interfered and tried to do too much to try and solve a relationship for brothers, or for brothers and sisters, whereas the siblings, by the time they got to be adults, thought they probably could have worked out some of these issues by themselves. There’s a lot of learning that we get from our parents, but there’s also a lot of behaviors that we get from our parents if they are overly involved where maybe they shouldn’t be involved.

Brett McKay: You mentioned just now that in your research you talked to men throughout the ages, different age demographics, from their 20s into their 90s, you even highlighted. Let’s talk about how do friendships change for a man as he goes through these different decades of his life. Let’s start with the 20s. What does a typical man’s friendships look like when he’s 23, 24, 25?

Geoffrey Greif: Pretty much across the lifespan what happens is that friendships when you’re in your late teens, early 20s take on great importance. Even from the time we go to kindergarten, the teacher sends home a report of, “Johnny plays well with the other kids.” Or, “Johnny has friends.” It’s always been on the radar. It stays on the radar through adolescence and young adulthood. What tends to happen is when people get married, and again, we’ll just assume a heterosexual marriage at this point, that the man tends to have less time for his friendships, and tends to put more time into his relationship with his spouse, tends to put more time into his job, because he’s climbing the career path or trying to hold onto his job, and tends to, of course, spend more time with his children.

The hardest thing for all people, men and women, to balance in relationships is time. How much time do I, as a man, have to spend with my male friends, without my wife around? How much time do I have for me alone? How much time do I have for just my wife alone? How much time do my wife and I have for our couples friends? How much time do we have for family? There are a lot of different spheres of time that we have to try and balance. In the 20s, assuming somebody gets married in their late 20s is when some of those old friendships might get let go in favor of spending time with one’s wife and trying to build a relationship with that wife. In the 30s, you have children in many families, and then of course it just takes up more time. What’s interesting is that when children are first born, fathers tend to spend time around sports that the father or mother has entered the children in.

If I grew up playing tennis, and I played tennis on my college tennis team, I’m probably going to put a tennis racket in my kid’s hand before I’m going to put a soccer ball in front of the kid. Maybe we’ll go to tennis lessons and I’ll meet other fathers that are sitting there watching their kids, and then we make friendships around tennis. Maybe the father and I go and hit some tennis balls, because he’s like me. As the child reaches 7, 8, 9, 10, maybe the child says, “I don’t like tennis, I like soccer.” Or, “I like football.” If I let the child play football, I’m then going to be hanging out with football dads who I may not have as much in common with. There may some distancing there from people that I might meet through my kids.

A lot of people in our study said they made friends through their children, who obviously make friends in school, college, work, and through your children, and sometimes in the neighborhood too, or through common interests, biking, chess playing, basketball, whatever you do. Then, of course, it’s in the … I’m skipping the 40s because it’s a little bit more of the same. In the late 40s or early 50s, depending upon the age of one’s children, that all of a sudden the children are saying “Dad, get out of my life, but first drop me and Susie off at the mall.” Or whatever the story is. The father then finds that his marriage, hopefully, is stable. His children no longer need him. Hopefully his job is stable, though that’s much more up in the air than it was generations ago with the many job changes that we see in society.

That’s when men begin to say, “I really have more time on my hands now. Saturdays can go back to me again. My kids are doing their homework, or they’ve left for college, or they’re playing sports and they don’t need me, they can drive themselves.” That’s when men start to need their male friendships more. I have out another book on how couples make friends with other couples. That’s when couples begin to hang out again together with other couples, in their 50s and 60s when both mom and dad, or the husband and wife, or it could be the husband and husband, and the wife and wife have more time to themselves, and they’re looking for meaning. They may start to connect again with other couples, once that couple’s kids are out of the house too. That’s sort of a brief look across the lifespan.

Friends become very important in the 60s, 70s, 80s, though we begin to lose friends as they die, as they move to Florida or Arizona, if you live in a Northern clime, and you don’t see them as much anymore. Maybe they’re spending more time with grandchildren, if they’re involved in grandchild rearing and helping out there. One of the things that I learned from the Buddy System is that a lot of them said they couldn’t make friends again. Their only true friends were the ones that they had from when they were children, or when they were in college. I try to disabuse people, though it’s hard to do, of the notion that you can of course make friends at the age of 75 that become good friends. I agree they won’t know you as they did when you were 20, but it doesn’t mean that you can not value that relationship that you can build now. That can become very beneficial to your happiness and your well-being.

Brett McKay: There’s a lot to unpack there. Going back to that idea of friends becoming more important as you get older. It was really sad, so my grandfather died last year, he was 100.

Geoffrey Greif: Wow.

Brett McKay: One of the things that he would talk about, you know, it’s like, “Grandpa, how you doing?” He would say, “Oh … It’s just … I had to go to another funeral.”

Geoffrey Greif: Right.

Brett McKay: He’s like, “All my friends are dead.” You could tell it affected him. He had his family, but he didn’t have his friends anymore.

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah.

Brett McKay: That was hard on him. I think that’s another issue we’re going to start running into more as the lifespan starts extending thanks to advances in healthcare.

Geoffrey Greif: Absolutely.

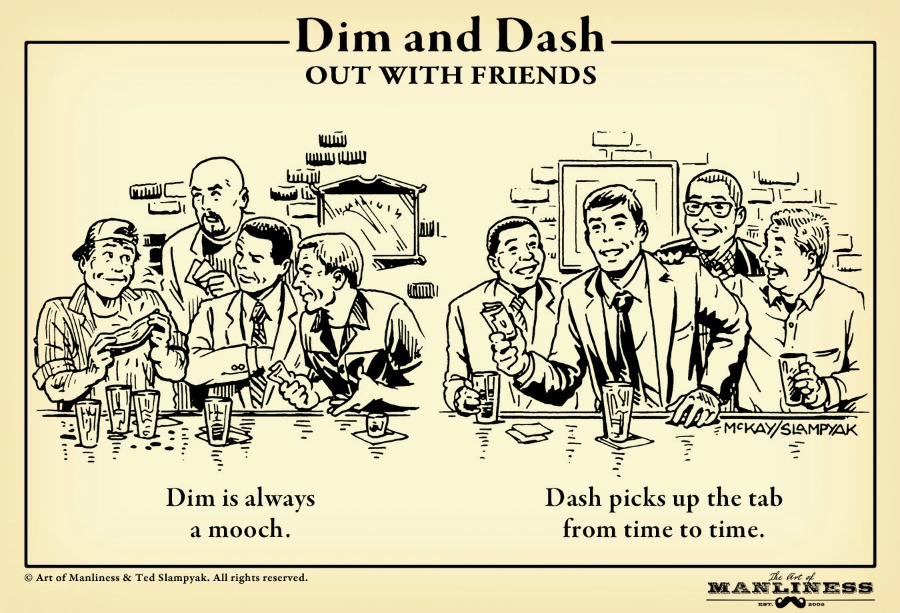

Brett McKay: Going back to this idea of couple friends, because I’d love to dig into this, because I think whenever you get into 30s and you’re married, I know for a lot of men, that’s how they make their friends. They don’t have time to go out by themselves and … Or they feel they don’t have the time, or they feel bad for going off by themselves. They rely on their wife, basically, for their social life. How does that play out, though? Because that’s a weird dynamic. The wives might get along together, but then the men, you know, they may not hate each other, but they don’t have a lot in common. When they get together it’s like, “Uh …” When you interviewed the men in your study, did they talk about that dynamic?

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah, there’s the general dynamic about we like him but we don’t like her, or you like her but I don’t like him. That happens in every couple that … It’s rare, not every couple. Some couples, and I’m sure you, if you’re partnered, and I and my wife have couples where we really like both members of the couple. I don’t care if I’m talking to one of them or the other one. There’s always going to be someone who you like a little bit less, and maybe you’re convincing your partner, “We really need to spend some time with them.” And she’ll say, “Okay, but let’s make it for a movie so I don’t have to talk to them that much.” That kind of thing, there is that balancing. I think, and I talk about this in Two Plus Two, the couple’s friendship book, there’s a broader way of looking at this. There are couples that we were able to classify, Kathy Deal and I, into seekers, keepers, and nesters. Forgive me for going through these three categories.

Brett McKay: No, I love it, this is great.

Geoffrey Greif: Seekers are couples that are always looking to add other couples. If I go out to dinner with my wife and we happen to chat with a couple at the next table, we’ll say, “Oh, you know, come on over for dessert.” You’re always sort of looking to add people. These are, obviously, extroverts in general. It’s impossible to have too many couple’s friends because you just love talking to people.

There are keepers, which is a large a group of folks, that have a lot of friends, or a lot of obligations with their children, or family members. They’ve got friendships, they’re open to other couples, but they’re not out looking to add to their pile of couples friends. That’s a fairly common experience to have enough friends, and enough family, and not really looking to add on. Then, there are nesters, who tend to be introverts, or tend to be couples that are marrying, maybe, for the second time, or finding each other late in life, and really only feel comfortable with very few other couples, want to spend time with each other, maybe alone, or with one or two couples and tend to be introverts.

Now, I talk about couples as being similar. They are not. I am a seeker, and my wife is a nester. She would rather hang out with one or two couples only. I am the kind of guy that picks up other couples at the restaurant and say, “Come on over.” That can be a little bit annoying to her, so she pulls me in to the middle, and I pull her more into the middle. We have to balance that. We have to have a discussion, so these categories are a way for couples to talk about how much do we want to add friendships to our lives, what do we want to do with keeping the friends that we have.

There’s another axis to think about which cross-cuts this, which are whether or not you are emotion-seeking or fun-seeking as a couple. A lot of couples are fun-seeking. They want to go out and play golf together, have a nice dinner, see a movie, and they don’t want to get into heavy stuff. They want to keep it light. If you have a very packed-in week, and you just are a busy person, you’ve got a lot of stuff going on, a lot of people, especially men, don’t want to go out and have some heavy, emotional talk on the weekend.

It goes back to the shoulder-to-shoulder friend, face-to-face issue we raised a little bit ago. But there are also people that want to have the emotion-seeking couples feel really comfortable and want to connect with people around emotions. Emotion-seeking people also like to have fun, but they’re interested in really a much more in depth discussion. Those are men that are going to be more comfortable having a face-to-face conversation. That’s how we can think about these couples on two axis. Number one, are you seeking more couples, or are you comfortable with what you have, or do you really want to keep the small number that you have, and secondly, what do you want to do with your friends? With that blueprint, couples need to talk about that and think about, “What do we want to do with our friendships?”

Brett McKay: What is the dynamic like for friendships where it’s just like the man has his friends, nothing to do with the wife, the wife has her friends, nothing to do … Did you talk about that? Is that like a source of tension?

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah, we talked about that. Usually, couples can ideally come to some understanding. “Look, why don’t you go out with your male friends tonight? I’ll go out with my female friends tonight. I appreciate Joe is a good friend of yours, but I really don’t want to hear his talking anymore about sports, because all you guys talk about is sports when we’re together. Why don’t you go hang with him, and I’ll either hang alone, or I’ll go hang out with one or a number of my friends.”

As long as couples talk about this, and they are clear … The other side of this is of course, for men, if we’re focusing on men is some wives don’t want their husbands to go and hang out with certain guys, because especially when they’re younger, they’re not a good influence on them. If you are a recently married couple, and your wife has sort of taken you away from your fast crowd of guy friends, you may, as the wife, be understandably uncomfortable with him, with your husband going back to the bar, hanging out with the friends, and you’re worrying that they’re going to get into some kind of trouble, or drink too much, or whatever it is they’re going to do.

She may slowly try and wrest her husband from those friends. Then, she’s going to need to find other male friends, other couples friends to take the place of those friends. That can be a struggle too. Some women surreptitiously look for friends for their husbands, because some women said they don’t think they’re husband has enough friends, or their husband has talked about having enough friends. They’ll be on the lookout for girlfriends of theirs that are married to guys that they think their husband might enjoy being with.

Brett McKay: Right. That whole dynamic is like, “Well, do they actually get along?” And the frustration and the tension there. Going back to the life cycle, and the influence of fathers on friends. As you said, in your 30s your life is basically, you’re running. I’m in my 30s. That’s how I feel like. I’ve got work, I’ve got family, I’ve got other responsibilities, and yeah, sometimes I feel like I don’t have time for friends. At the same time, if you think about the influence that you have on your children, I’m thinking, “My son and my daughter, they’re watching me. If they’re seeing that I make no time for friends, then they’re going to not put an importance on that.” It’s important to me, and I want to pass that on. It seems like it’s sort of a perpetuating cycle. You’re in your 30s, you make this focus not on friends, and it results in your children not putting an emphasis on friends. You have to be very intentional about breaking that.

Geoffrey Greif: Right, and I think the advice I would give to anyone in your siltation is to find other couples that also have children, and get both families together so they see you interacting with both other men and other women too. You can then get a sense about what values around friendships you want to pass on to your children. Now, you have to find couples that have children that match up with your children. That’s another layer of difficulty in this friendship match. The other message to give your children, goes back to what I said before is, I don’t know if you have siblings, but you would want to also try and have good relationships with your siblings so their children and your children, as first cousins, can be close, and so they see that they should be close also with their own siblings.

Brett McKay: Man, socializing is complex. Friendship is super complex.

Geoffrey Greif: Yes.

Brett McKay: Based on your research and the talks with the men you’ve done in your book, how do most friends go about making friends? I’m sure there’s a lot of men who are listening to this, they want some more friends, they just don’t know how to do it. Based on your interviews, what did you find?

Geoffrey Greif: Yeah, well if you haven’t made them in school, and most of the men that are listening probably are out of school or are soon to be out of school, school is the natural place to try and make friends. The next stops on the friendship train would be work and would be the neighborhood, and then through your own kids. The interesting thing about men trying to make friends is you have to get involved in things that you like to do. If you like to play chess, join the chess club. If you like to bike, go to the bike store or go biking and try and chat up people there. You don’t make friends staying home and not being open to it. You have to get out there. You have to organize things.

Have a football party to go back to men and sports, and invite over a number of men. Some men may feel uncomfortable only inviting over one man, and it goes back to the fear of appearing gay. A subtext in all of this is that there were a significant minority of men in my book who said they were afraid to appear gay by approaching men to be their friends. Again, my research was a decade ago. That’s not as much of an issue today as it was then, but believe me, it’s still an issue for some men regardless of their age.

One guy I talked to on the plane who I met had just moved to a new city and he would meet guys and would want to be friends with them and maybe would call them up once, but if they were not available, he didn’t want to call them again. He didn’t want to seem like he was stalking them to be a male friend. That’s not something that men like in other men, this notion of, “I’m emotionally needy and I want to be your friend.” There has to be some comfort in approaching other people and doing it in a way that is not appearing overly needy. There’s always the question of, “How much do I open up to somebody.” A lot of men don’t like too much emotional vulnerability too soon. They want to wait a few times before somebody opens up to them. If you want to make friends, part of it is gaging the person you’re with and how open are they to hearing some of the things that you may or may not want to talk about. It’s having a radar out that can read some of the other guy’s feedback to you.

Brett McKay: It sounds like you’re probably going to start off just friends, right? With these.

Geoffrey Greif: Right.

Brett McKay: Because you’re just doing stuff with them. Then, sort of through the natural origin of the relationship it might turn into a trust friend or a must friend.

Geoffrey Greif: Nice. Nicely said.

Brett McKay: Okay. Well, Geoffrey, this has been a great conversation. I’m curious, is there anywhere people can learn more about your work? Because it’s not just friends you talk about. You talk about sibling relationship, couple friends, is there a place where people go and can see all of this stuff that you’re doing?

Geoffrey Greif: Aside from my bio at the University of Maryland School of Social Work where I’m a professor, you can look at the books I’ve read, or you can go to Amazon and look at those books. I have a new book I’m working on, on in-law relationships, and we’ll have some interesting data on how sons-in-law and fathers-in-law maintain this very unique relationship as compared with mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law.

Brett McKay: That sounds really fascinating. Geoffrey, thanks so much for your time, it’s been an absolute pleasure.

Geoffrey Greif: Thank you, I’ve greatly enjoyed it, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Geoffrey Greif, he’s the author of the book, Buddy System, Understanding Male Friendships. It’s available on Amazon.com. He’s also got a lot of other books that he’s written about couples and friendships, siblings and friendships. Check it out, it’s all there on Amazon. Also, check out our show notes at AOM.is/buddysystem, where you find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at Artofmanliness.com. If you have enjoyed this show, have gotten something out of it, please take a minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Helps out a lot. As always, thank you for your continued support, and until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.

Tags: Friendship