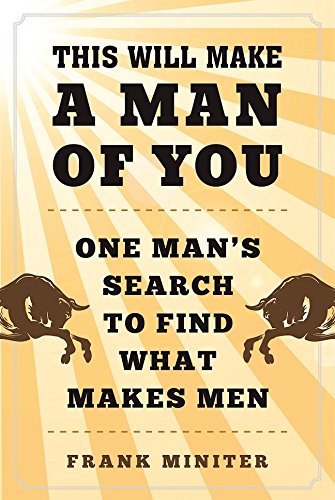

Last summer, I had Lesley Blume on the show to talk about her book Everybody Behaves Badly, which gives the story behind the story of Hemingway’s first big novel, The Sun Also Rises. On today’s show, I talk to an author of another book about this landmark novel, who, instead of providing the historical context of The Sun Also Rises, explores the ideal of manliness Hemingway was trying to get at in the book. His name is Frank Miniter, he’s a journalist and the author of previous books like The Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide. His latest is called This Will Make a Man of You: One Man’s Search to Find What Makes Men.

Frank and I discuss Hemingway’s project of creating a new myth of manliness that combined traditional notions of masculinity with modern sensibilities, how Frank Sinatra killed the rugged gentleman and made “cool” a defining feature of modern manliness, and what the running of the bulls can teach us about rites of passage into manhood. We end our conversation talking about Hemingway’s attraction to and repulsion from bullfighting, and why the matador was Hemingway’s ideal symbol of manliness.

Show Highlights

- How Frank became interested in Hemingway, and particularly Papa’s code of manhood

- The attributes of a “Hemingway Man”

- How the idea of “cool” kills the old-school gentleman

- How our culture of cool influences society’s idea of manliness

- How Hemingway was, in a modern way, trying to capture traditional ideals of manhood

- What Hemingway’s main characters often have in common

- Does suffering make for the best learning?

- The purpose of Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises

- The religious themes in The Sun Also Rises, and Hemingway’s Catholicism

- The history of Pamplona’s running of the bulls

- Frank’s own experience running with the bulls 13 times

- What makes for an effective rite of passage

- Why Americans don’t respond well to the running of the bulls or bullfighting

- The background and cultural significance of bullfighting in Spain

- How matadors, in many ways, encompass Hemingway’s ideal of manhood

- Why culture today looks down upon codes of honor and manhood

- Why everyone should meld the traditional and the modern to form their own code

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide by Frank Miniter

- My podcast with Lesley M. M. Blume about the origins of The Sun Also Rises

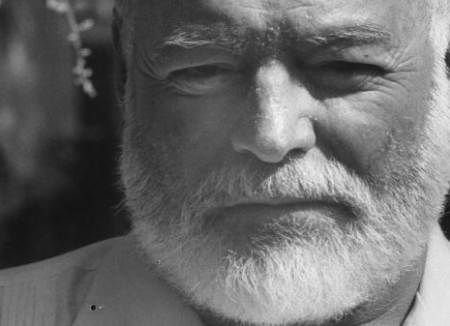

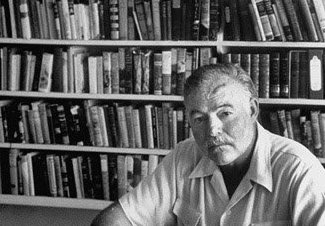

- The Libraries of Famous Men: Ernest Hemingway

- Ernest Hemingway Motivational Posters

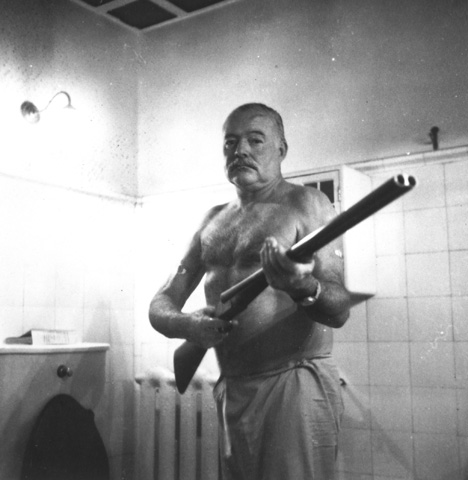

- Ernest Hemingway’s Guns

- The Hemingway You Didn’t Know: Papa’s Adventures

- My podcast with Matthew Crawford about The World Beyond Your Head

- The Rise and Fall of “Rebel Cool”

- AoM’s Series on Manly Honor

- Joseph Campbell

- My podcast with Waller Newell about the code of man

- Getting Over Your Glory Days

- Reading Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises by H.R. Stoneback

- The Camino de Santiago

- The Running of the Bulls

- How to Create Your Own Rite of Passage

- The Importance of Male Rites of Passage

- How and Why to Develop a Mighty Moral Code

- The Bushido Code

- The Song of Roland

This Will Make a Man of You is one of my favorite books that I’ve read this year. Frank does a great job making explicit what Hemingway made implicit in The Sun Also Rises. I had several “a-ha” moments while reading the book. Pick up a copy on Amazon. While you’re at it, pick up a copy of The Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide to brush up on your man skills.

Connect With Frank Miniter

Frank on Facebook

Tell Frank “Thank you!” for being on the podcast via Twitter

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Mack Weldon. Their underwear and undershirts are second to none. If you don’t like your first pair, you can keep it, and they will still refund you. No questions asked. Go to MackWeldon.com and get 20% off your purchase using the promo code MANLINESS.

Blue Apron. Check out this week’s menu and get your first three meals free by going to blueapron.com/manliness.

The Great Courses Plus. They’re offering my listeners a free one-month trial when you text “AOM” to 86329. You’ll receive a link to sign up and you can start watching from your smart phone… or any device immediately! (To get this reply text, standard data and messaging rates apply.)

And thanks to Creative Audio Lab in Tulsa, OK for editing our podcast!

Recorded on ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Frank Miniter, welcome to the show.

Frank Miniter: Thanks Brett, good to be here with you.

Brett McKay: I’ve been a fan of your work. You wrote a book, “The Ultimate Man’s Guide to Survival,” or something like that. It came out the same time as my first book, “The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners.” It was fun to see that. It’s a really handsome looking book. You’ve written some other stuff, but your latest is one that I just absolutely loved because it’s about a book, one of my all-time favorite books, “The Sun Also Rise,” by Ernest Hemingway. A few months ago, we had a gal on the podcast who did sort of the history of that book, how it came to fruition of Hemingway’s time in Paris and what was there. What I loved about your book, is you really focused on Hemingway’s exploration of manliness and his code of manhood that he was trying to get at with, “The Sun Also Rises.”

You talked to a lot scholars on Hemingway, you actually went to Paris, you went to Spain, did the Running of the Bulls that “The Sun Also Rises” made famous. You just give these great insights that I never really thought of. Start off, what inspired you to do this exploration of “The Sun Also Rises” and to go to Spain, to do the Running of the Bulls, and to watch bullfights?

Frank Miniter: I’m a journalist and as you know that I wrote “The Ultimate Man Survival Guide” and that got into the question of, “What makes man?,” through, “What are the skills a man should know?,” and all that kind of stuff. That’s the beginning to that conversation. I had a lot of people coming to me saying, “Okay, that interesting and great. We enjoyed the book, but what really makes men? What is it that create character? What builds these people? What are we losing today that’s supposed to build people into all they want to be, to men, all they’re supposed to be?” I started asking that questions of myself, and it’s just a very philosophical and hard question to answer.

As I looked around, I thought, “Okay, Ernest Hemingway was kind of the icon for manliness, especially in the early 20th Century, but he was attacked, especially in the late 20th Century by the Feminist Movement, so on, as being a parody of what a man was supposed to be.” He was supposed to be a chauvinist pig and all this. He did have four marriages, and loved alcohol, and these kinds of things, and it started to lampoon and destroy him. I thought, “Okay, if he’s been attacked as my first love so … his writing is still loved so much but attacked so much, then there’s a lot there. There’s a lot in his writing, and who he was, and who he was trying to become about manliness, about answering that question. Let me start to investigate, just for my own before I even start writing, let me figure this out.”

I started actually following that path and ended up with this crazy bunch of people, this wonderful bunch of people, men and women, who follow that Hemingway trail every year from Paris to Pamplona, which is that route from “The Sun Also Rises” that those expats took on that pilgrimage. I ended up with this incredible group of people in the history of Paris, in the cafes in Paris, seeing that intelligent side that Hemingway was supposed to also personify. He believed in that whole dichotomy of man where you were the sophisticate yet you were the adventurer as well, one was not without the other, you were that well-rounded ideal. Then we went to Spain and ran with the bulls in Pamplona and went through that whole intense rite of passage.

I ended up finding out that there is just so much more there than I ever imagined, not just with “The Sun Also Rises,” and those characters, and knowing where they were, but why Hemingway took us there and why he found so much depth in that place in those times. I ended up turning it into a book into a real answer to that question, “What makes men?”

Brett McKay: Yeah. We’ll get into some of those insights that those ritual, or those rites of passage, can teach us. Throughout the book, you said you were on this search for, what you call, the “Hemingway Man.” You mentioned just now that part of being a Hemingway Man is being well-rounded, being a sophisticate, also this rugged adventurer. What other attributes does a Hemingway Man possess?

Frank Miniter: It’s that grounded in something real, in something actual. It’s why he was a hunter, in my opinion, and a fisherman. That’s reality when you go hunting and you become, actually, a part of nature. It might not be for everybody, and I’m not making that argument, but it certainly is real. Those Spanish Bulls, that he also loved, are real. He loved that ideal of the authentic life, and the only way to get the authentic life is to deal with reality. We’re dealing with generations now who interact more through social media, and enjoy video games, and other kind of pursuits, which are all fine and good, but if that becomes your reality, that’s an alternate reality. That’s not real reality. That doesn’t shape someone into who we really want them to be and who they really want to be. That takes reality to do.

That’s what the Hemingway Man was all about. That’s why he was real in those Paris cafes. He was friends with Pablo Picasso, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and a lot of those painters and writers of that age. He also made fun of the café trash. He didn’t like the posers, the fakers, the wealthy who came to that part of Paris to live this certain bohemian kind of life, because he saw them as fakes. They weren’t really artists. They weren’t really suffering to become what they wanted to become. They were faking it. They were wearing the clothes of it, but they weren’t really becoming that thing. He ended up mocking those people and really being attacked in the end by those people, a lot of the critics who those people became. What the Hemingway Man really was and was supposed to be is somebody who bases himself on reality.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s why he sought out adventures his whole entire life, was an ambulance driver during World War I, did the hunting, boxed, fished, all sorts of adventures because it was real.

Frank Miniter: Yeah. He went to war. He actually went into the Spanish War. As you noted, he went to World War I as an ambulance driver. He sought out those real adventures. The deep sea fishing, he went with his … He was actually looking for U boats at one point in time. In World War II, he went back in in a slightly controversial way when Paris fell back into the hands of freedom. I know he liked to be at the cusp of all of those things, the real things, that developed character. It’s why he said that a bullfighter was the only one who lived life all the way up, because they were standing toe to toe with a bull who could kill them and does kill a lot of matadors.

I’ve been to bullfights and seen bullfighters get put down. It happens a lot. It’s a very real experience. Say what you what you want about it, he was after that real experience, the authentic life.

Brett McKay: Right. Earlier on in the book, you had this great dichotomy about the ideal of manliness that Hemingway captures. Our idea of manliness that we have today, and a lot of people have today in modern culture, is this difference between being cool and the old school gentleman. You said, “This idea of cool kills the old school gentleman.” How did that happen? Can you explain that a little bit more?

Frank Miniter: Yeah. I was quoting the late Michael Kelly who was killed in the War in Iraq, a journalist, a great writer. He noted that, okay, Frank Sinatra was the king of cool. He was really our first big time pop idol. Right? He came in after the smart set and redid the … Smart Set* believed, before him, the Humphrey Bogart kind of ideal, was that you lived the right life, you were that stand-up person, and by being good, you were good and became all you were supposed to be. Well, he looked at that and he said, “Well, wait a second. No, I’m the king of cool and I’m personifying this idea where if there’s a fight that has to happen, you have guys who will take care of that.”

He kind of stood back from what that was supposed to be, at least his image did, I don’t think he really did as a person. That became the image. Michael Kelly noted that and said, “Wait a second. This killed the smart set and it no longer was cool to do the right thing. Now, it was cool to do the wrong thing.” It was a big shift in culture that led us to where we are today with pop culture moving this direction. I would look back to James Dean and his iconic role, “Rebel Without a Cause,” as really as a part of that whole movement, the beginning of that. I mean, through that movie James Dean is weak. I mean, he’s this iconic, wonderful character and a great movie, but he’s so weak and he keeps asking his father, “What does it take to really be a man?”

His father, through the whole movie, never has an answer for him, which is what that movie is about, I mean, that’s the theme. Now, that’s, what, back in the 1950’s. Since then, we really haven’t answered that question, at least our society, our mainstream society hasn’t. What Frank Sinatra and what Michael Kelly was noting that, “King of cool killing what is supposed to be right and good,” is where it’s left us. Guys like us who are trying to answer that question for ourselves and find the answers for people need to get out there, as we are, to show people that, “Wait a second, being right and good and being that courageous upstanding guy isn’t necessarily a bad thing.”

That’s actually who you want to be. Being this sarcastic person who’s kind of off to one side and who doesn’t really get what that is, what that basis of them really is, they’re lost and they’re going to stay lost until they re-find what Hemingway was showing us.

Brett McKay: Right. I feel like the culture of cool is just sort of an indifference. You don’t want to appear like you’re trying too hard because that’s not cool. Cool is just like, “Hey,” you’re like the Fonz. You could just hit the jukebox with your elbow and everything happens magically.

Frank Miniter: Right. People back in the greatest generation, right, World War II, they went to war. All segments of society joined the military and went to war and fought for that cause. Now we’re in a period, and post-Vietnam, rightly so, where we no longer believe we can really fight for good. We can’t really know what’s good and wrong, right and wrong. Good and evil are not simple concepts the way they were to previous generations. We’re kind of lost in this moral relative universe. People are searching for it though, it’s here. I think we could find our purpose again, but it’s going to be up to this generation to read and think, as we are, to find these answers again because it’s there.

I think the people who are that stand-up person, who create that business and become that person they really wanted to be are the type of people who have found that foundation under themselves.

Brett McKay: How did Hemingway capture that idea of the old school gentleman, the smart set? One criticism, or one people say that what Hemingway did is, he was very cynical about things like honor in war because of his experience in World War I. A lot of his characters, they seem a little detached from ideals because they’ve just been burned. You argue in the book that it might appear like that on the surface, but Hemingway was actually, I don’t know, trying to capture those ideals and somehow make it a bit more modern.

Frank Miniter: Yeah, he was trying to reform them into something that’s palatable today. I mean, Joseph Campbell put this very well, he said, “Every generation has to create a new myth.” What the myth becomes is a way to finding that answer that might be the same answer, but it’s a way to understanding that answer because it’s going to evolve over time as we evolve, as a society evolves. I mean, Hemingway wrote the “The Sun Also Rises” and published it in 1926. I mean, women got the right to vote in 1920. He was at a very different age than we’re at, but he was trying to look at those old ideals that had been dashed in World War I and say, “How do we bring them forward? How do we take them and give them to this new generation?”

Now we’re several generations past that, but how do we find them again? What are they? What are they supposed to be? Hemingway has often been, a lot of writers have said it, a lot of scholars who look at Hemingway have said that he was always in search of the code. He was kind of obsessed with the code even. What is his code? He never really articulates it in a list of rules, but if you read his body of work, you find out that he absolutely was obsessed to a code based on things that he thought were authentic.

Brett McKay: What were some of those things that were part of his code?

Frank Miniter: Being that stand-up guy, it’s back to this favorite metaphor of the bullfighter or the hunter in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” In that story, Francis wounds a lion, and then when they need to go in and finish off that lion, which is a dangerous thing to do, he chickens out and runs away when the lion charges. The professional hunter has to kill the lion. Well, then you have Francis without his manhood. He has to re-find his manhood. The only way he can do that is to stand up and prove himself physically again, which he does right at the end of the story with a charging cape buffalo. He’s a tragic figure. He gets killed by his wife, shot in the back of the head in that story. Whether it was on purpose or not, Hemingway leaves open, but he gets killed and a lot of Hemingway’s heroes are like that.

Santiago, in “The Old Man and the Sea,” catches the great fish but he gets taken by sharks. Always losing these kinds of … In “Whom the Bell Tolls,” the hero gets killed in the end. The hero is always dying or losing as we’re going to. We’re all mortal, we’re all going to die, but he’s making the point that you can’t always decide what’s going to happen in your life. You can’t control very many things in your life, but what you can try to control is how you take it. If you can stand up the way that bullfighter does to that charging bull and stand up full of courage and full of … not to put down the bull or something, but to stand up to that ideal and keep your feet straight, and your back straight, and so on, then you’re doing this right.

You’re doing what we need, because a person in a crisis, man or a woman in a crisis, who keeps their head, they’re the ones that save a life. They’re the one to help us. They’re the ones who stop the lynch mob and so on. That’s the stand-up kind of guy he was pointing us toward with all these different metaphors.

Brett McKay: Right. He has that famous line about, you’re going to face defeat, that famous quote, “The world breaks everyone, and afterwards some are strong at the broken places.” He really believed that, this idea of the furnace of affliction that would make us stronger in the end.

Frank Miniter: Right. He also said that, “The thing that makes a writer is an unhappy childhood,” these kind of ideas that you do have to suffer in order to learn, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Yeah. One of the characters you talk about in “The Sun Also Rises” is sort of a contrast to Jake, the main character, who was sort of based off of Hemingway and his way, sort of autobiographical, is Robert Cohn. He exemplified the complete opposite of Hemingway’s codes. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Frank Miniter: Yeah. Throughout the book, Robert is weak. He can’t marry the woman he wants to marry, or the second woman, the woman he’s dating in the beginning of the novel, in Paris because he’s too weak to do that. He can’t stand up to that ideal. He ends up running away and having a little fling with the novel’s heroine, Brett. Then she throws him off and decides she’s done with him and moves on to the next guy. He keeps following her, and haunting her, and getting in the way, and making all the situations very uncomfortable because he’s too weak to deal with that, to get over that as a man, and it’s throughout the book. He even fights the bullfighter in the end, because that bullfighter is then having an affair with Brett Ashley, and he can’t stand that.

He keeps knocking down the bullfighter in the end of that book because Robert was a boxer and knew how to fight when the bullfighter did not. The bullfighter continually gets up again and again. I forget how many times he gets up, but it’s so many times. Then finally Robert just can’t hit him again, he just doesn’t have the gumption to do it. He just thinks, “This is wrong somehow.” Robert is stuck in this boyhood code where the toughest guy on the street is the man. He hasn’t grown into that mature ideal of there’s a time to fight and a time not to fight, and pretty much you shouldn’t fight unless you’re in self defense. He keeps knocking down, the bullfighter just won’t stop.

He runs into a guy living on a code, a guy who stands up to his life. That’s a pretty deep metaphor for how a man should be. When you contrast Robert with Jake and how they behave, and how they treat people, and how they forgive people, then you really see what Hemingway was showing us about being a man.

Brett McKay: Right. Also Robert exemplifies a great symbol of … You said, he’s stuck, he’s arrested development, he’s still in adolescence because he-

Frank Miniter: Yeah, and he actually calls him that. Absolutely.

Brett McKay: Right. Right. I mean, he still talks about his glory days in college like, “I was this at Princeton. I was a championship boxer. Blah-blah-blah-blah.” Throughout the novel, he’s always talking about, “Well, I want to go do this. Maybe I’m going to go to South America. Maybe I’m going to … ” He just talks about these abstractions, right, but never gets down to living real life unlike Jake.

Frank Miniter: He wants to go off to the purple land, the dream land that he read in a novel about South America. Yeah, the main character there, Jake, basically Hemingway, is telling him that there’s no such place, that if you want to live your life all the way up, start living it right here in Paris. Start looking under your feet because the foundation is there, which becomes the vehicle for the whole novel because they go on a pilgrimage, which I would argue and Harry Stoneback does it very well, is really a religious pilgrimage. It’s following a pilgrimage to Saint James, which has been, through the Middle Ages, it was a religious thing to go and find yourself on that long path to the shrine in Saint James.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, let’s talk about that in a bit. I mean, Robert Cohn, if you are a young man who’s feeling restless like you just feel like you can’t move on in your life, you need to read “The Sun Also Rises.” Pay attention to Robert. You don’t want to be like Robert.

Frank Miniter: We all know those guys. We all know a few of those guys, never got in that fight in high school, I’m not saying we all should fight, but never physically proved themselves and are kind of stuck in this place. If someone could just help them, if that right man was in their life to help them live up to who they want to become, they could just do anything. You just feel sorry for them and you want to help them. Most of them find their way eventually, but it would sure help them if they the right mentor earlier.

Brett McKay: Right. Let’s talk about this religious pilgrimage, because I had no idea about this, the religious undertones behind “The Sun Also Rises,” which doesn’t make any sense because it begins with a Bible verse from Ecclesiastes. Throughout the book, it’s just infused with all those religious symbolisms. You talk about this pilgrimage they went on from Paris to Spain. Who originally started that pilgrimage? Was it a Saint of some sort?

Frank Miniter: Well, they’re going to see one of the Twelve Apostles, Saint James, who’s, legend has it, his body was moved and buried there at that church at Saint James. That’s what the path is going to, to see that shrine. It’s really about the pilgrimage, not so much about actually kneeling down at that shrine. It’s that pilgrimage, it takes two to three months depending on what path you take, walking that path, that through nature, through that whole experience, it’s supposed to shape you and you’re supposed to then find yourself and your purpose in life. That’s what that has always been about. That’s what he was taking those people on through that novel.

Brett McKay: Right. Jake was the one leading these lost generation guys to this pilgrim so hopefully they would find themselves along the way.

Frank Miniter: He never tells them that. That’s a lot the reason why it’s lost. I mean, it was Hemingway’s theorem of a mission, that iceberg that 90% of it’s under water. It’s beautiful because the depth is there and you can feel it, but you’re not being hit over the head with it. He practiced that in “The Sun Also Rises.” That’s why a lot of people do miss it.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean, I missed it completely. Another thing you talk about is Hemingway’s Catholicism and how it influenced. He was born a Protestant, correct, and he later converted to Catholicism?

Frank Miniter: Right. He converted during the second marriage.

Brett McKay: How did that influence his writing after his conversion?

Frank Miniter: I don’t think it did. I think it’s the Protestant upbringing that influenced him throughout his life. Converted to Catholicism, he was divorced from Hadley and he joked, and I don’t know how serious he was, but he said this, “I became impotent,” really from guilt, from cheating on and then divorcing his first wife and marrying Pauline Pfeiffer. Sometime during that period, his second wife said, “Well, okay. Why don’t you go to this chapel,” she was Catholic, “Go to this chapel, convert, ask for forgiveness for your sins. Maybe that will bring your mojo back,” which he does. He goes and he converts and he gets forgiven for his sins. He says from then on, he was a king of bed … how he put it exactly, in a very coarse kind of way.

Everything with Hemingway was always that … if he wasn’t conquering something outside of himself, he was conquering himself. Fine. I don’t think that Catholicism, in that way, shaped him or changed him. I don’t think he was a very devout kind of guy, but he grew up as a Protestant, as a Christian, with a very religious mother, especially. He learned the tendancy to that early on and he sought those answers. Even when he was Paris, he found scholars, and I quote some of this in the book, he found scholars who taught him about that pilgrimage that he ended up taking the fictional characters on in “The Sun Also Rises.” He found the purchase for it, so the depths of it were there but I don’t think it was as much Catholicism, it was just his childhood upbringing.

Brett McKay: Right. Speaking to Hemingway’s … he was married four times, I think it’s interesting, he always got a new wife before he started a new book. He always divorced the wife when he finished the book, and then he got a new one when he was starting a new one.

Frank Miniter: It seemed to work that way with him, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Right. It’s kind of bizarre. All right, so let’s talking about the Running of the Bulls, this festival in Pamplona, Spain. Hemingway is the guy that made this famous, because I think before “The Sun Also Rises,” very few people knew about it. It was primarily a festival that the people in Spain took part in, the Bosque. What’s the history behind the Running of the Bulls? When did it start, and why do they do this thing where they have bulls chase them in the street?

Frank Miniter: Yeah, it grew through the 17th, 18th centuries. They combined two festivals … Oh, the late 16th or 17th Century … A religious festival with a fair into one time frame that became the San Fermin, the festival we know. They were taking the bulls to the arena through that 17th and 18th Century. People just started going with the bulls, it was kind of a, “Here come the bulls, let’s follow them.” It just developed into this run, into this test of yourself, by going with these fighting bulls down the street. This isn’t the only one in Spain, there’s a lot of them in Spain actually, this is just the most famous. This is actually a very normal rite of passage for Spanish youth, as is getting into the ring with the those cows with leather on their horns, which Hemingway did do.

Hemingway didn’t actually run with the bulls. It grew out of all that through those centuries. By the time Hemingway found it, it was a very mature fiesta. He was there and witnessed it, and he couldn’t believe it. I mean, he wrote some early stories for the newspaper he was then writing for, the Toronto Star, where he talks about it. Read that again, and it’s kind of he’s shocked about it all. He’s surprised. He following the crowd here to there and he can’t believe it, and that’s when he became addicted to it. Then he came back again and again and learned about it and ended up writing about it more, and of course, wrote the great novel.

Brett McKay: Right. What’s your experience with the Running of the Bulls? How many times have you done it?

Frank Miniter: I have been in the street 13 times with the bulls. I’ve had a couple of very close calls, but I haven’t been injured. I’ve run every section of it. I’ve been very lucky. As a journalist, I’ve always been taught, “Find a mentor. Find someone who can teach you,” because if you’re trying to write about it, you need experts. Find that expert. I found a guy named Jaun Macho. That’s actually his real name. He’s a Cuban, moved to Miami when he was 12 years old and he still lives in Miami. He was just drawn to this fiesta, being a lover of Hemingway himself and a Hemingway scholar himself in the early 1980’s. He’s been running every year since then. He’s run well over a hundred times with the bulls.

In the last decade or so, he started to take people under his wing. He wants to teach them. He found that a lot Americans, especially, and a lot of foreigners come in there, they don’t know how to run with the bulls. It’s a real test and the Spanish know about this, but they don’t know how to do it. They end up doing stupid things in front of the bulls and really getting hurt when it wasn’t necessary to get hurt. He became my mentor and showed me how to run with the bulls. Of course, he put me in the street my first time all by myself because he says you face your mortality alone. When you go through something, especially that first time running with the bulls, because what you have to do is you have to enter the street at 7:30 in the morning because they would close the barriers at 7:30, but the bulls don’t come until 8:00 in the morning.

This happens eight days in a row. You’re waiting there for 30 minutes for the bulls to come. Around you, at the beginning of that, everyone’s boastful, and excited, and, “We’re going to do this and that with the bulls,” because the street’s always more than half full with first time runners. As it gets closer to 8 o’clock, and that rocket’s going to go off, and the bulls are going to come out and run down those streets, you see people start to fall apart. I wrote about this in book, my first time running, a guy next to me from Chicago was boasting about what he was going to do. By the time it got close to 8 o’clock, he’s losing it. He kept picturing himself being disemboweled by a bull.

He decided, “I have to get out of here. I have to get out of the street.” He tried to go under the fence to get out of the street and a Spanish cop kicked him back into the street, looked at him, and said, “You wanted to be a man and run with the bulls, now you must be a man and run with the bulls.” They don’t let you out of that street once they close those barriers and they do that for a reason, because if people try to pile out and they panic and try to get out of that street, you’ll end up with a log jam in the street and these bulls will come and they’ll hit that log jam. They have forward facing horns, I mean, there’s 12, 1,500 pound bulls with forward facing horns. If there’s a big knot in the street, they’re going to kill people.

They’re doing that for everyone’s good, actually, but the person didn’t understand that and he went under the barrier for a second time. This time the cop didn’t kid around. He just hit him, boom, boom, boom, and put him down. I’ll bet you he spent that night in a Spanish jail. That cop was showing us, he was kind of the drill sergeant to our real rite of passage there showing us you had to stand up now, “You’re in the street? Now you’ve got to stand up and you’ve got to be a man.”

Brett McKay: Yeah, you said earlier that this Running of the Bulls is a rite of passage for Spanish youth. It used to be primarily for men, but now women. There was a time when women couldn’t do it, but now women can.

Frank Miniter: Right.

Brett McKay: A major theme throughout the book and as you follow Hemingway’s footsteps is this idea of a rite of passage. From your experience following Hemingway from Paris to Spain and doing the Running of the Bulls, what did you learn about what makes for an effective rite of passage into manhood?

Frank Miniter: Yeah, this is what I did with the table of contents and the whole structure of the book, because this is so key. I went through this in military school, and I’ve talked to people who’ve gone through special forces, and became New York firefighters, and all sorts of occupations that have real rites of passage. They’re always kind of the same way. They’re always the same structure and it’s really interesting. They’re first designed to scare the heck out of you somehow, to reset you, to take you down a notch so it can build you up into what you really need to become through this rite of passage. Running with the bulls, that first one, of course it’s that first time you run, it just tears you up. You can’t believe how much it changes you. It’s wonderful stuff.

If you go to the bootcamp, which is a really classic rite of passage that follows this kind of structure, that first day when you have a drill sergeant yelling at you, and you had your hair shaved off, and you go through that whole metamorphosis of yourself, you also go through that first trial by fire where you, “Okay, now you’ve been burned down, you’ve got to be built back up.” Then it starts to build you up. You need a guide, there always has to be a guide in any real rite of passage. Then you need a gauntlet that it will take you through that you prove yourself through a step by step. One time running with the bulls is great, I think it’s wonderful.

A lot of people just do it once and they walk away from it and they’ve got a great cocktail story to tell. They’re probably a little bit changed by it, but it’s not what really grew them up into something. Dealing with the people that I know through this now who’ve run again and again, hundreds of times, with the bulls, it slowly changes them, and builds them, and they find their courage through it, and they learn to respect the bulls very deeply because of this. They don’t molest the bulls in the street, for example. If you do that, that’s breaking the code that’s beneath it. It’s also part of the big rite of passage. Every rite of passage has a code.

If you molest a bull, he’s going to turn around in that street and he’s really going to hurt people, you grab his tail, you do something to him. There’s a code to it in every rite of passage. There’s always a code beneath it. You’ve got to find that code, and then you have to live up to that code and that’s what every rule in a rite of passage does, and this certainly does. As you go through this process, at the end of it you respect the bulls, you understand why you’re doing it, you learn you courage through it, and you walk away a very different person, which is always what a rite of passage was supposed to do, to build the boy into a man or now a girl into a woman. I mean, it’s wonderful now that women run with the bulls as well.

Brett McKay: Yeah, this idea of the code and respecting it, I think when people, outsiders, look at the Running of the Bulls and bullfighting in Spain, they think it’s just barbaric. Right? There is this very serious code you must follow and if you do not follow it, there are serious repercussions. You talk about the bulls that go into the arena, they have leather horns, and you can run away from them but you’re not supposed to touch them. What happens if you do mess with them?

Frank Miniter: Yeah, if you molest a bull, which I saw firsthand right in front of me, people who just didn’t know the rules tried to jump on them, and grab their tails, and so on. The Spanish guys there who go into this kind of thing, they will literally beat the hell out of you in a way that would get them arrested in America, and they have lawsuits, it’d shut down the whole thing. No one will stop you, and the crowd, there will be 20,000 people watching when this happens. What happens is, okay you run the bulls and if you want to you can run all the way into the arena. Then they close the barrier behind you and the bulls go out.

Then they let these bulls in one by one, which these things travel town to town. It’s like rodeos. Right? The bulls, they travel town to town. These bulls travel town to town and they know how to throw people. You can’t fool them with a cape or something, because they know. They know how to get the person. If you watch it from above, you’ll see people just popping up over and over again as these bulls run circles around nailing everybody, which is a classic Spanish rite of passage. You’re right, if you break that code, you molest that bull, boy, I’ve seen a couple of people get put in the hospital. I mean, just totally taken down and beaten down for breaking that code.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so there’s a strong sense of honor that you have to follow. If you do not follow it, you will be shamed and possibly physically beat.

Frank Miniter: Right. A lot of the Americans I talked don’t understand that and they, “How dare they? How can they possibly do this?” When you go through all this process of explaining to them, “Well, there’s a reason why they’re doing all of this.” Then they go, “Oh, okay.” They just didn’t know. They didn’t understand that.

Brett McKay: I think an interesting point too you make about rites of passage is that, it’s not a one and done thing. I get a lot of men who’ve written me and say, “I never had a rite of passage into manhood,” and they try to go seek it out through some sort of vision quest or they do some sort of adventure. I think a lot of them, they think that’s going to be the thing that going to make them feel like a man, but then they come back disappointed and let down because it didn’t. I think it might be because you can’t just do one. It’s not a one and done thing.

Frank Miniter: You’re always developing your character. There are certain Native American tribes that used to earn a new name as you went through life and you proved yourself according to this new rite of passage you went through. That was a real direct way of saying what you were trying to do. Yeah, as you go through life, you’re going to find there’s different ones. Understand the rules, that’s why I went to such pains to explain in the table of contents and the structure of my book. It helps you find them. It helps you understand them. It helps you grow through them. Yeah, you’re going to run into different ones as you go, hopefully, through life, different challenges as you each time try to grow up into a new ideal.

If you’re going to stop in time somewhere, well that’s your choice, but then you become just a case of arrested development like we were talking about earlier, that person who still talks about their glories as the quarterback in high school. You have to move on to the next thing and the next challenge and grow up into that new one. That’s what being a man is all about.

Brett McKay: Right, so constantly seek out rites of passage. There’s not a one and done thing. Let’s talk about bullfighting because this was interesting. It’s an extremely controversial sport for obvious reasons. Can you give us a little bit of the background of bullfighting? Why do Spanish cultures have bul fighting? Where did that originate from?

Frank Miniter: Well, you can go back to the Romans when they’d fight bulls in the amphitheater. They were doing it on horseback with spears. In the 15th Century, somebody came along who, I think they were actually knocked off their horse, and someone ran out to save them with a piece of cloth and end up keeping that bull of him until they saved him. They got that idea, “Wait a second. This is what we can do.” Then you ended up with some people trying it and it became a famous way of fighting the bulls actually on your feet with that cape and then killing them with a sword, which is a lot more heroic than doing it on horseback.

It developed slowly over a long period of time, but you look at it now and it’s, what, four or five centuries old, at least, with a lot of pomp and a lot of … If you go to one in Spain, it’s full of music. It’s set up in a very regimented way, a very choreographed way where that bull comes in and he goes through three steps. I mean, Hemingway looked at this and he said, “I’m not going to defend bullfighting. Bullfighting isn’t a sport, it’s a tragedy.” He’s right, it’s a great tragedy played out right before your eyes. It’s a hunter killing its game. I mean, it’s any of us who, well any of us who live on this planet. I don’t care if you’re a vegetarian because if you’re a vegetarian you’re still eating vegetables and some farmer has to protect those crops in order to grow them, and in order to protect those crops, he still has to kill deer, or mice, or geese, or something that might be eating his crops. If not, he’s just going to be growing crops for that wildlife.

We’re all a part of this system. Bullfighting is just a very loud and visual way of seeing that. It’s putting it right in front of your eyes and showing you and celebrating that circle of life that we all are a part of. My first bullfight, I sat there, and as a long time hunter and stuff, you think I’d be immune to this, but I sat there and I was in tears my first bullfight. It was so emotional for me where I literally had an old Spanish woman in front of me who was giving me some cakes, and some wine, and stuff before the bullfight started. Then by the time it started, I was in tears and the guy next to me is also upset. We’re two Americans in our first bullfight and she turns to us and looks at us and goes, “Oh, you’re just like all the rest of the Americans. You’re just so weak. You can’t handle this reality.”

She had a point. At the time I thought, “Well, what does she mean?” It took a long investigation for me, as an American who grew up in the American culture, to understand what they were trying to show us. As I look at it now, I think it’s a celebration of life, actually, with that bull dying, a bull that wouldn’t even really exist, it’s bred for this purpose, if it wasn’t for bullfighting. I think if somebody watches it, and tries to understand it, and has a problem with putting this kind of death of that bull on display for applause from a Spanish audience, okay I can understand that view point. I could see them being against it as long as they’re trying to understand it.

Unless they’re trying to understand it and they’re just opposed to bullfighting, then okay they’re knocking down a culture they don’t understand and they really need to open their eyes and educate themselves.

Brett McKay: What are some of the things that people misunderstand about bullfighting or maybe the ethics of bullfighting?

Frank Miniter: Yeah, it’s that death of the bull that gets them, and it is bloody. The picadors come out first and so on, and it starts to bleed. They’re weakening the neck by literally bleeding the bull’s neck until it’s not picking its head up high enough so the guy in the end after all, all the runs with the cape and all that, he can kill it with the sword, which to kill it with the sword, that takes a perfect thrust over the top, down through the chest, and into the heart, the heart area so that bull just goes down and dies immediately. What happens is, if that matador doesn’t do it perfectly, if he’s not pulled off, if he’s especially messing up the end with the sword, but whatever he’s doing, or if he’s showing cowardice in the arena, whatever he’s doing, he’s failing as the ideal he’s supposed to be. He’s not killing as cleanly as he’s supposed to, that Spanish crowd, I mean, they will go nuts.

They will start hissing, they will start throwing their seat cushions. In the extreme, the governor of it will actually pull that bullfighter out and really embarrass him. Someone else will have to go in and kill that bull. You’re supposed to go in and do it ethically, and cleanly, and quickly when it comes down to actually doing the kill. There’s a whole code beneath how that’s supposed to happen and show a deep respect for that animal. I understand that it’s hard for somebody not of that culture to understand that this is actually respect for the bull by killing the bull this way. I mean, all these bulls are eaten. I’ve eaten the bulls that actually have been killed in the arena.

It’s just hard for someone to understand that just as it is hard for someone who doesn’t hunt to understand hunting. How can somebody kill a deer, or a bear, or whatever and then be seen in the picture smiling with that dead animal, even though they’re going to eat the animal later? To them, as a non-hunter, that’s an appalling idea. I challenge people to understand the nature of the world we live in, and who they are, and the whole process of the thing before they condemn something they really just don’t understand.

Brett McKay: Right. It’s all about bringing reality back and putting it right in front of us. There’s-

Frank Miniter: It’s on display, tragically.

Brett McKay: Yeah, there’s cows getting slaughtered all the time that you eat in your prepackaged container, saran wrapped container. This is how it’s done. You need to see this, basically.

Frank Miniter: I actually jumped down with one once right after they killed the last bull and got into the place Pamplona there, at the Plaza de Toros, to where they cut up the bulls and got to meet the guys. They do it fast and they put them up. It’s like seeing beef taking up, boom, boom, boom, boom, and gets cut up, and it’s being sent to the restaurants there in Pamplona. You see that whole process at each part of it, and you realize that they’re showing us in a very visual display that we’re all connected to the world we live in.

Brett McKay: Right. It’s going back to this idea of manhood. Hemingway said that, “The matador is probably the ideal of manliness.” Just as you were describing it, they’re on display in front of everyone and if they don’t do it right, if they don’t follow the code, they’re going to be shamed, and booed, and hissed out of there, and possible taken out, which is just even more shameful. Yeah, there’s that connection of bullfighting and just trying to show this ideal of Spanish manliness in a very visceral upfront way.

Frank Miniter: Yeah, it’s public. It’s on display. If they show the least bit of cowardice in that arena or don’t kill cleanly, if they don’t follow that code to the ideal, yeah, they’ll go right down in a huge embarrassment and maybe they’ll be hurt badly in the process.

Brett McKay: Right. Going back to this idea of codes, we talked about Jake’s code, we talked about Robert’s lack of code, but I feel like we live in a culture today where we look down on codes of honor with skepticism and cynicism. Why do you think that is?

Frank Miniter: One reason is, we see them as being too simplistic. We don’t really believe anymore that a person can be heroic in sense they’re fighting for something good, because we don’t believe a person can know what’s right and what’s wrong. We used to believe that we knew, that was a religious idea, but we believed we could fight for good. We’ve lost that idea, and there’s some good from that because it’s led people a lot of depth. Then you’ve put a code of honor from in front of something, and I’ve put a lot in the back of this book for this reason. They look at it as just being too simplistic. When I look at it I say, “Yeah, but you’re trying to articulate a foundation for yourself.

You look at these codes and you try to develop your own code, which I think every man should do, because no one of these codes can be relevant to themselves. They have to write their own and think about this process. Then when you find yourself into those situations in life, your first reaction if you follow this code will be to do the right thing because you’ve already established who you are what you’re living up to. That’s what a code always did, but your society think they’re too simplistic, they’re tearing them down. They also look at them, of those knight’s codes, and the code of Bushido, and the gentleman’s code, and they look back at them, especially in this feminist idea, they look at them and they see them perpetuating this certain chauvinistic kind of ideal that gentleman of the 19th Century who oppressed women.

As I said, women didn’t get the right to vote until 1920. I mean, they’re still fighting for some of their rights. They look at that and they say, “Oh, you’re trying to push us back to some kind of ideal from before and bring these chauvinist values back up, and we don’t want to live back in that society now that we’ve reached a new one.” When I say, “Wait a second. If we were to look at codes, if we look at how they developed, you notice that codes really became purified in the early 20th Century during the Feminist Movement.” In the 1930’s, 1940’s, you could see that clearly in film where they became much less, chauvinism dropped, and the racism was dropping away. It was becoming clean. They were becoming good.

Right at that same time, we decided codes were useless because they were pointing backwards. When I say, “Wait a second. Write your own code. Look forward. Make a better code. Make a code that isn’t racist, and sexist, and all these kinds of things and find … ” I think also if you look, you won’t find the racism and the sexism written in those codes, even the code of Bushido, the old Japanese Samurai’s code, it said, “Everyone is inherently equal.” The Samurai’s actually saying that. They always saw that ideal as well, but I think today we have to understand that again, refashion that to ourselves, and understand you can have that basis again. Without that basis, I don’t see how you could possibly be the stand-up guy you want to be.

Brett McKay: We said earlier that Hemingway was trying to fashion a new myth, a new ideal of manliness, this sort of, “Look to the old codes while transforming it and making it new.” What do you think that ideal looks like? What did Hemingway end up creating through that metamorphosis that he was trying to do?

Frank Miniter: Yeah, you feel it through all of his literature. It’s this guy, and it’s Jake, and it’s hard to put your finger on Jake in “The Sun Also Rises,” that main character, because he’ll never come right out say, he’s showing instead of saying what he’s living up to. There’s several times in that book where he takes Brett to different chapels to pray and she feels uncomfortable doing that, but to him that’s the old values. The Roland that I talk about, the ancient myth, “The Song of Roland,” is behind a lot of the Hemingway’s writing. There’s a reason for that. One of the chief mythological knights became mythologized in “The Song of Roland” from the Middle Ages, it was their ideal for them to be in the Middle Ages, of that stand-up person living this upstanding bigger way.

Jake is trying to show that to the character and so on, but he never comes right out and says it. I don’t think Hemingway ever decided to come out and preach that kind of thing. Reading all through his letters, you see him telling you how to behave but never really telling you, never really spelling it out. Here’s the rules you have to follow, let me just show you, stand up to yourself, be courageous. “How you take life,” which is chief metaphor on everything, “How you take what comes to you. If you can take it as that stand-up guy, then you’re going to grow into the ideal you want to be and it’s understanding then what’s around you, what’s underneath you in that process that will grow you into the man you want to be.

Brett McKay: Well, Frank this has been a great conversation. There’s a lot more we could talk about. Where can people learn more about the book and your work?

Frank Miniter: “This Will Make a Man of You” is on Amazon, it’s on Barnes and Noble, really wherever books are sold. You can find me at frankminiter.com. I also write a column weekly for Forbes. You can go to Forbes.com and find me there. I’m all over the place.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Frank Miniter, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Frank Miniter: Thanks Brett.