Watching a holiday movie is a great way to get into the spirit of the season and has become an annual tradition for many families. But what exactly makes a Christmas movie, a Christmas movie, what are some of the best ones ever made, and what makes these gems so classic?

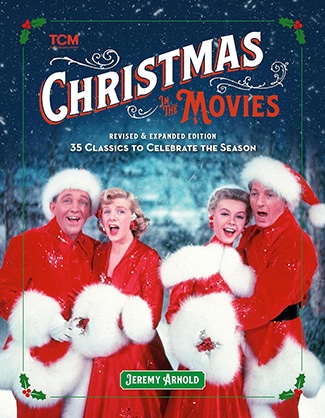

Here to answer these questions and take us on a tour of the highlights of the holiday movie canon is Jeremy Arnold, a film historian and the author of Christmas in the Movies: 35 Classics to Celebrate the Season. Today on the show, we talk about what defines a Christmas movie, why we enjoy them so much, and why so many classics in the genre were released during the 1940s. Jeremy offers his take on the best version of A Christmas Carol, whether Holiday Inn or White Christmas is a better movie, why he thinks Die Hard is, in fact, a Christmas movie, what accounts for the staying power of Elf, and much more. At the end of the show, Jeremy offers several suggestions for lesser-known Christmas movies to check out when you’re tired of watching A Christmas Story for the fiftieth time.

Movies Mentioned in the Show

- Santa Claus (1898)

- Scrooge (1901)

- Scrooge (1935)

- Miracle on Main Street (1939)

- Remember the Night (1940)

- The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

- Holiday Inn (1942)

- The Man Who Came to Dinner (1942)

- Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

- It’s a Wonderful Life (1947)

- Scrooge/Christmas Carol (1951)

- We’re No Angels (1955)

- Cash on Demand (1961)

- Die Hard (1988)

- Home Alone (1990)

- Home Alone 2 (1992)

- The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992)

- Elf (2003)

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Watching a holiday movie as a great way to get into the spirit of the season has been an annual tradition for many families. But what exactly makes a Christmas movie a Christmas movie? What are some of the best ones ever made? And what makes these gems so classic? Here to answer these questions and take us on a tour of the highlights of the holiday movie canon is Jeremy Arnold, a film historian and the author of Christmas in the Movies: 35 Classics to Celebrate the Season. Today on the show, we talk about what defines a Christmas movie, why we enjoy them so much, and why so many classics in the genre were released during the 1940s. Jeremy offers his take on the best version of A Christmas Carol, whether Holiday Inn or White Christmas is a better movie, why he thinks Die Hard is in fact a Christmas movie, what accounts for the staying power of Elf, and much more. At the end of the show, Jeremy offers several suggestions for lesser known Christmas movies to check out if you’re tired of watching A Christmas Story for the 50th time. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/christmasmovies.

Alright, Jeremy Arnold, welcome to the show.

Jeremy Arnold: Thanks so much for having me, Brett.

Brett McKay: So you are a film historian, a commentator and author, you’ve done a lot of work with Turner Classic Movies, TCM. I’m curious, what led to your interest in film?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, I guess I would have to give credit to my father for that. At a very young age, he introduced me to classic movies of the ’30s and ’40s. He had been born in the ’30s and grew up in Brooklyn, and his favorite movies were always Warner Brothers’ movies of the 1940s. So at a very young age, I was becoming very familiar with Humphrey Bogart, Barbara Stanwyck, James Cagney. Those are the earliest classic film stars that I was aware of, and I still love that period more than any other. And I just became obsessed with classic cinema. And I started to notice that when I saw certain names in the credits, especially the directors, like Alfred Hitchcock or John Ford, or Lubitsch, or Anthony Mann, I just… I started to figure out that those names usually meant some special quality, or just excellence in general. And that’s how my film education started. And then I went to college at Wesleyan University, which has a really great film department, and I just became fascinated with how the creative choices a filmmaker makes can dictate audience response. And I made some short films and came to LA, started working in the industry, all kinds of jobs, and just eventually fell into writing and working in the world of classic movies.

Brett McKay: That’s great. So you got a new book out in time for the holiday season. It’s Christmas in the Movies: 35 Classics to Celebrate the Season. So watching Christmas movies has become a tradition for, I think, most people here in the United States. We’re gonna talk about some of our favorite classics. But let’s talk about the history of Christmas in cinema. Do we know when the first Christmas movie was ever made?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, the earliest one that I’m aware of is from 1898, and it’s a film called Santa Claus. And it’s a little over one-minute long. It was made by a British filmmaker, and it’s been preserved by the British Film Institute. You can find it on YouTube. It’s… In its own way, it’s quite charming. And then in 1901 is what is considered the first version on film of A Christmas Carol, and that one’s about, I think, three or four minutes long. Also available on YouTube and also pretty good, given the context. Although it is hard to screw up A Christmas Carol, ’cause it’s such a rock solid story.

Brett McKay: Right. We’re gonna talk about A Christmas Carol. So hey, Christmas has been a theme in cinema over 120 years. That’s a long time. And something you point out in the book though, is that a lot of the Christmas movies we consider classics were made in the 1940s. What was going on? Why there were so many Christmas movies that are timeless made in that time?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, I think the short answer is World War II. That’s the defining event of the 1940s. And this isn’t to say there weren’t Christmas movies made in the ’30s, the first full decade of the sound era. There were, but there’re just not that many of them. There was a British version of A Christmas Carol in 1935. There’s a little B-movie called Miracle on Main Street, which I do write about in the book. Came out in 1939. But the ’40s, the first half of the decade was defined societally by families breaking apart as millions of Americans went off to war. So families were fracturing and breaking. And after the war, in the middle of the decade, families were reuniting. And sometimes they weren’t, because their loved ones had perished. So the whole idea of family, the unity of family, the growth of family, and the breaking apart of family, this was happening on an enormous scale. Everyone was affected by it to some degree. So what I’ve noticed is that Christmas starts to pop up much more frequently in 1940s movies, including in movies that I wouldn’t even characterize as Christmas movies, where the season maybe plays a small role in representing the family unit, in some way, for that film. In the full-fledged Christmas movies, it injects real meaning into the storytelling, so meaning to the characters’ journeys, the stories’ concerns, the takeaway that the audience takes from the film.

And I just think that because the whole idea of family was so widespread and top of mind for so many people, Christmas just became a really smart sort of shorthand for representing family on screen, and you see it used in so many different ways.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So a few examples of that. Meet Me in St. Louis comes to mind, is all about families breaking apart and having to change. That was done 1944. And then shortly after that… Well, you have I’ll Be Seeing You, another one, 1944. Same theme. And then after the war, you have the same… You saw the same thing, people having this longing for home and family. I mean, It’s a Wonderful Life, that’s what it’s all about.

Jeremy Arnold: And especially, I talk about how the year 1947 is sort of the peak Christmas movie year of the peak Christmas movie decade. You have It Happened on 5th Avenue, Miracle on 34th Street, and The Bishop’s Wife, all opening that year, and lots of other movies with Christmas in them opening throughout the year. I did some research and I found that from January through December 1947, there was pretty much a consistent presence of Christmas on movie screens, through the entire year. That speaks to a couple of things. First, the war, it ended two years earlier. And it takes a year or two for a movie to get made and released, so if the end of the war had had this effect, even unconsciously, on filmmakers, it would have taken a couple of years to start manifesting in cinemas. The other thing it speaks to is, and this has to do with the fact that the movies opened throughout the year, a lot of Christmas movies in the ’40s opened at odd times of the year; spring, summer. And I think that speaks to the whole notion of using Christmas as a meaningful storytelling device, and not just as an excuse to open a movie at Christmas time, which is usually the case today.

Brett McKay: What makes Christmas such a great narrative device?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, I think because we all experience Christmas every year. Whether we observe it to some degree or another, we all live through it. We at least observe it, if not experience it. And so it comes with a built-in audience recognition and understanding. And if you have a story about a fractured family and the story gets to the Christmas season, you just know that this is a time where the family should be together, where you want them to be together. And maybe the story isn’t allowing them to be for whatever reason, and it’s using Christmas to point that out, to make a contrast or to highlight that idea. So there are so many recognizable rituals of the season; visual, oral, that we all experience, and so it’s very relatable.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and I guess that date, December 25th, it gives the writer of the film, and the audience too, that there’s a tension. We all know it’s leading up to the 25th. Something has to happen by then. And that anticipation that we all experience ourselves in the holiday season leading up to 25th, that can drive a story line. Really powerfully.

Jeremy Arnold: Oh, absolutely. There’s so many Christmas movies that culminate on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. Some go a little beyond to New Year’s. But the idea that Christmas is a time of healing, of rebirth, of love, being formed, of being able to open up and tell them that you love them, that sort of thing is so linked to Christmas.

Brett McKay: Okay, so the real life longing for family togetherness during World War II added it a longing and a sincerity… It added an earnestness to these movies made in the ’40s that I think still resonates today and has made… Help make these movies classics. How did Christmas movies change in the post-war period?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, I think you start seeing a shift from wistfulness and the idea of a complete family unit, from that to one of nostalgia, which is most exemplified by the movie White Christmas, I think, which is really driven by nostalgia and driven by these characters’ desire to do something for their former army commander. You also start seeing Christmas used in more subversive ways, the black comedies, like We’re No Angels. You got it… I know we’ll talk about A Christmas Carol later, but the 1951 A Christmas Carol is quite darker than the Hollywood version made in the ’30s, and I think that’s more appropriate to this time than the other one would have been. And you start getting variations in the ’60s, like Cash on Demand, which is a variation on A Christmas Carol, but it’s really a bank heist movie. So I think Christmas starts being used in different types of genres. And this actually speaks to something else, really important, which is Christmas movies were never a genre back in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s. No one ever said, no filmmaker ever said, “I’m making a Christmas movie on Stage 12.” The term didn’t exist. The term came later with hindsight. And we have since retroactively labeled these movies Christmas movies. And people define the term Christmas movie in different ways, because there is no accepted generic definition.

And so this is why when we love to debate whether Die Hard or any other film is or isn’t a Christmas movie, what’s really being debated are competing definitions of the term. For one… Someone’s definition may not allow for Die Hard, and someone else’s does. And that’s just the way it is. Both are valid, because Christmas movie, the definition of it is very subjective. It’s really whatever you like to watch every year at Christmas time, and that may be a movie that doesn’t even mention Christmas and it’s just some pure escapism, and that could be arguably defined as a Christmas movie as well. It’s just not the definition that I went with.

Brett McKay: Yeah, speaking of a Christmas movie that’s not even really about Christmas, I know in England, The Great Escape is a Christmas tradition there, for some reason. And so people watch The Great Escape every year at Christmas time.

Jeremy Arnold: Yes, and so are James Bond movies. There are marathons of Bond movies on British television every holiday season, I think, because they’re so purely escapist.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So how do you define a Christmas movie for yourself?

Jeremy Arnold: So I define it as any movie of any genre in which some aspect of the holiday season plays a meaningful role in the storytelling. So as I said before, meaningful to the story, the character arcs, the audience takeaway. And the thing is, is that this Christmas season can mean many different things. It can mean, on one end of the spectrum, joy, family togetherness, love, positive transformation, but it can also mean loneliness and despair and alienation, cynicism, the feeling that Christmas is insufferable and overly saccharine, is too commercial. All these things are aspects of the season that I think we all feel at one time or another in our lives, [chuckle] or even at one time or another in a specific day [chuckle] during the season. And so it really allows for a very wide spectrum of movies that we could call Christmas movies, from dark tragedies to cheerful cartoon-ish fantasies.

Brett McKay: Okay, so let’s dig into some of the movies you highlight in the book, and let’s start off talking about movies based on the Charles Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol. So you mentioned the first adaptation of that on film was in 19… Early 1900s, 1901. How many film adaptations have been made of this story?

Jeremy Arnold: I have no idea.

Brett McKay: Okay. [laughter] It’s probably a lot.

Jeremy Arnold: There are too many, or too many to count, because I’m sure there are lots of versions that I’m not even aware of, which were made in other countries, for other animation, puppetry movies. Well, there is one, The Muppet Christmas Carol. There are variations in almost every genre, probably except sci-fi, which doesn’t really mix with Christmas very well. [laughter] But yeah, it is probably the most adapted novel or story in the history of cinema.

Brett McKay: That’s a great story. Do you have a favorite version of the Christmas Carol in film?

Jeremy Arnold: My favorite version is really the 1951 British version, starring Alastair Sim, which was a released in England as Scrooge and in America as A Christmas Carol. But a close number two is The Muppet Christmas Carol.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What makes that 1951 version… What sets it apart?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, first of all, the casting. Alastair Sim was a very controversial choice to play Scrooge. He’d been known as a comic actor. Really just for comedy. And when he was announced in the lead for that, this is months before the film even started production, there were letters written to newspapers and movie magazines decrying the whole idea of casting Sim. “How could you do this? How could you taint the Charles Dickens classic with a comic actor like Alastair Sim?” Kind of amazing that people would go to the trouble of doing that before the movie even opened or was made. And the producer of the film wrote a response called Why I Chose Sim, [chuckle] in which he defended his choice. And the bottom line is the movie came out and he was brilliant. It didn’t matter that he was only known for comedy, he was just a really good actor and was able to play the tragedy and the joy, everything in between in that character.

Another thing that sets it apart is what I would call the horror element. Christmas Carol gets really dark in parts, especially when we’re with the Ghost of Christmas Future. And the darkness is necessary because Scrooge is so dark, and he must confront that. And it also makes the joy of the ending all the more powerful. Like It’s a Wonderful Life does the same thing. So it captures the loneliness and despair of the season, as well as the joys, the lows and the highs. And just like It’s a Wonderful Life, which has a lot to thank Dickens for, I just think it embraces the season in a more complete way than some of the other versions, which are almost all good, by the way, because it’s such a rock solid story. It’s really hard to mess it up. Oh, and also the sense of period London is really strong in the 1951 version. The director, Brian Desmond Hurst, really worked hard to do that. And he drew inspiration from the illustrations by John Leech in the original publication of the Dickens novel, which were very plentiful. It was an illustrated novel that way. This film was planned for a big premiere at Radio City Music Hall, but once the organizers saw the film [chuckle] and saw how dark it was and bleak, they cancelled it. [laughter] So it’s kind of amazing to think, but the movie did not do well commercially, or critically, in the United States. Not till much later.

Brett McKay: When did it become a critical and commercial success?

Jeremy Arnold: I think more in the 1970s and ’80s, when it started saturating television screens, just like It’s a Wonderful Life and a couple of other titles were doing. It was sort of re-discovered then, I think.

Brett McKay: Well, that’s another interesting point about the Christmas film genre. Television plays a big role in their success. They typically don’t do well at the holidays, they’re not Box Office bangers. But once they get on TV, that’s when they become part of our culture.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah. Television has a really interesting push and pull relationship with Christmas movies. You could argue it helped create the very concept of the term Christmas movie simply by virtue of the fact It’s a Wonderful Life and A Christmas Carol and then Christmas in Connecticut, Miracle on 34th Street, they started playing on television all the time in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s. And I think that cemented, in a lot of the public’s mind, the idea of watching a movie at Christmas time that really has Christmas in it. At the same time… Oh, the same thing happened with A Christmas Story, by the way. That was not a big success when it opened, but then it found new life on cable television. But another thing about television is that it took over the production of what might have been Christmas movies in the ’60s and ’70s. There are very few movies in those decades that I think really are Christmas movies. So what was happening in television? All the Christmas specials that we still love, from the Rankin/Bass, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Charlie Brown, all of those. They took over the Christmas market, I think, in those years.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the Muppets Christmas special with John Denver. Like I still watch that one. Or Emmett Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas. So you mentioned Christmas Carol. Another favorite of yours is “The Muppet Christmas Carol”. And that’s my favorite because I just, I loved how Michael Caine played Scrooge, like he’s surrounded by these puppets, and he could have been kind of goofy with it, but he played Scrooge straight. He was like I’m gonna be Scrooge. And he did it like a professional.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah, he did. He said he was gonna… He said, I’m gonna play it like I’m doing this with the Royal Shakespeare Company [laughter] And that’s a great contrast when you have Muppets all around you being the Muppets. I just, I love that movie because it is such a faithful adaptation of the story, but it also gives us what we want from the Muppets the sense of irreverence and the crazy comedy. I mean, it’s just a perfect blend.

Brett McKay: Alright, so we can’t talk Christmas movies without talking about It’s a Wonderful Life. We’ve already sort of mentioned it, but what’s the backstory on that film? I know it originally wasn’t… It wasn’t made as a Christmas movie, I don’t think even… It didn’t even release around Christmas time. Is that right?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, it actually did get a limited release in December of 1946, although it didn’t open widely until January, 1947. It was sort of a last minute addition to the Christmas release schedule, because another movie by the studio, Sinbad the Sailor wasn’t ready for release. So they needed to slot something else into that slot.

Brett McKay: Was it a hit when it first came out?

Jeremy Arnold: No, it was not a hit. It lost money, but it was not a bomb. It wasn’t a huge box office bomb as sometimes is reported. It just didn’t do very well. And the way it came about was after World War II, Frank Capra had… He’d been changed by the war. He’d made war documentaries and propaganda films, and he’d been really affected by the imagery of war and combat that he saw. And so he was interested in making something darker than the films he’d been known for. And so he returned and formed a company called Liberty Films with William Wyler and George Stevens. And around this time, the story, the short story that “It’s a Wonderful Life” was based on, found its way to him. RKO had owned it and had been failing miserably in trying to adapt it into a screenplay. And so they sold it to Capra. And this was the problem. It was a mix of tones and it was hard to capture the balancing act of the tragedy and the darkness with the lightness and the warmth and comedy in the film. Capra liked it because of that mix, especially the darker aspects. And so he adapted it with three other writers into the screenplay that we know and brought back Jimmy Stewart, who he’d directed several times before. And it just really came out of all of those elements.

Brett McKay: Well, speaking of the war’s influence on this movie, so this was made after the war. We did a podcast interview several years ago with an author who did a history of Jimmy Stewart’s service as a bomber pilot during World War II. And one thing he noted was in that famous scene where George Bailey is basically… Hit rock’s bottom. He’s at Martini’s, and he says that prayer, and he starts crying. Apparently Jimmy Stewart kind of used his experience in war to summon those emotions that he conveyed in the film.

Jeremy Arnold: Yes. He did say that later on, and it’s a really powerful moment. I mean, this is George Bailey at his lowest point. It’s just before he goes to the bridge to commit suicide… To plan to commit suicide. And the the camera moves in. We have this intense closeup, and he’s praying and praying for any kind of heavenly help that he can get and that line, “I’m at the end of my rope. I don’t know what to do.” Very powerful.

Brett McKay: What do you think is the most Christmas-y scene in that film where you’re watching and you’re like, “Oh man, Merry Christmas. It’s here. I love the holidays.”

Jeremy Arnold: [laughter] Well, I mean, I would have to say the ending, the finale in the Bailey home where everyone is together and people are coming in and giving money to save everything. And he realizes that he’s the richest man in town and he’s with his family framed in front of the Christmas tree. And it’s joyful. I mean, it’s probably the most joyful finale of any movie ever made. ’cause we really earn that joy, not just George Bailey, but the audience, because the movie puts us through the wringer. It’s a really traumatic film at times with some real darkness in it. So it’s a very cathartic release at the end.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Okay. So another oft-overlooked Jimmy Stewart Christmas film is The Shop Around the Corner. And I watched this one, Katie and I, my wife, we were at a bed and breakfast around Christmas time, and we were just watching films. And The Shop Around the Corner was on, it was on Turner Classic movies. And we were like, “Oh, what’s this?” And we started watching it and we really enjoyed it. So what’s the basic plot of this movie and what makes it a great Christmas movie?

Jeremy Arnold: Well, this is one of the great romantic comedies produced and directed by the great Ernst Lubitsch. And it is a story set in a shop, and the employees of the shop are the characters in the film. And Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan play two coworkers who really can’t stand each other. They bicker, they argue, they get on each other’s nerves all the time, but at the same time, they don’t know this yet, but they’re each engaging in anonymous pen pal letter writing [laughter] with someone else. And they’re falling in love with this anonymous person that they’re each writing letters to. And it turns out that they’re writing letters to each other anonymously. And at a certain point in the story, Stewart figures this out, and it’s sort of, it’s a great moment where he just suddenly sees Margaret Sullavan in a completely different light and realizes that the person that he’s been bickering with on her surface is not who she really is.

And the same is true of him. And in time she comes to realize that too, it’s no spoiler to say they end up together at the end. I mean of course they do, but the way they get there is by scratching beneath the surface of things and being vulnerable and really seeing the inner core of the other person. And so it’s a really beautiful way that they fall in love. And what makes it a great Christmas movie is how the season becomes more and more present in the story and the frame, on the soundtrack as the movie goes on. And as these two characters fall in love, and you sort of get the sense that Christmas, the season is like a force that’s pushing these characters together, sort of nudging them to each other, but it also allows for a great mix of tones, not to the same degree as “It’s a Wonderful Life”. But in the same vein. There are subplots that deal with marital infidelity and the great pain that that causes, there’s a suicide attempt, like “It’s a Wonderful Life”. It doesn’t shy away from the darkness and the loneliness of life and of the season. And so it’s that mix of tone that I think makes it feel like a really complete movie.

Brett McKay: And if people are listening and they’re thinking, that plot sounds familiar. You’ve got Mail, the Tom Hanks movie is basically a reboot of this film.

Jeremy Arnold: It is… It is very consciously a remake. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So one thing about Christmas movies is some of our most cherished Christmas songs that we sing today around pianos and listen on the radio, they came from Christmas movies. And one of those songs is “White Christmas”, written by Irving Berlin and sung particularly by Bing Crosby. What movie did “White Christmas” debut in?

Jeremy Arnold: It debuted in the movie “Holiday Inn” in 1942, but it debuted as a song even before that. On Christmas Day 1941, Bing Crosby performed it on the radio on Christmas Day, and it became quite popular quite quickly. He made a commercial recording in the spring of 1942 just before “Holiday Inn” opened. Then the movie opened in the summer, early summer, I believe, and it was a big hit played all summer long. It was shown to troops abroad. The song became a really big hit around the world with the Armed Forces. And then the following year it won the Academy Award and for almost every year of the rest of the decade, it reached number one or close to it on the pop charts every holiday season. So, I mean, it is still by some measures, the single bestselling song in music history. What I find really interesting is the way that the song has sort of evolved in its meaning over the years when it’s in “Holiday Inn”, it’s used purely romantically.

It’s used to represent love between Bing Crosby and Marjorie Reynolds. He sings it to her and it’s a very romantic setting, and it’s a cozy Christmas time living room with a fireplace, that kind of thing, snowing outside, and he sings it really intimately and then she sings and they sing together. So it’s literally bringing them together in song and love. By the time of “White Christmas”, the movie in 1954, in that film, the song is not presented romantically at all. It’s presented purely on the basis of nostalgia. We first hear it in the opening sequence when Bing Crosby is in a war zone and he’s singing it to troops who are all sort of sitting with their heads hanging, clearly thinking about their families and homes thousands of miles away. And the song isn’t about love it’s about home and remembering home and wanting to be with family.

And at the end of the movie, it’s performed again in a huge musical number with a lot of characters on the stage. And it’s presented in a stage setting, performed in front of an audience in the film of veterans of their army friends and others. And so it has this great meta effect where you really get the sense that the people in the audience, in the film are not just thinking of home when they’re hearing the song this time. They’re thinking of their time together during the war when they became a family a band of brothers themselves. So it’s sort of layered that way. Really interesting. And I just think it’s fascinating how one song can take on such clearly different meanings.

Brett McKay: And what’s interesting about “Holiday Inn” and “White Christmas” is “White Christmas” is… It’s kind of a reboot of “Holiday Inn”. They play a lot of the same songs, you have Bing Crosby in it, and Holiday Inn, it’s Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. Phenomenal. They’re great. They wanted to bring back both of them for “White Christmas”. And Fred Astaire is like, “I don’t wanna do that.” And that’s how Danny Kaye got in there. Which one do you like better? Do you like “Holiday Inn” or “White Christmas” better?

Jeremy Arnold: I prefer “Holiday Inn”. It has a stronger story. It moves really quickly. It’s full of energy. “White Christmas” has a less strong plot. It’s a much more leisurely film and it’s long, it feels long. It’s two full hours.

Brett McKay: Yes.

Jeremy Arnold: Now I don’t dislike “White Christmas”, at least not that much [laughter] and it has grown on me over the years, but it’s just more about nostalgia than it is about love. And you get a stronger sense of human relationships forming in Holiday Inn, I think. “Holiday Inn” is also so funny and has such great dancing. A lot of people I think today know “White Christmas” more than they really know or see “Holiday Inn”. So I would encourage people to seek it out.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’m with you. I think “Holiday Inn” is the better film. I think “Holiday Inn” has a plot. There’s a story to it. The dancing’s great, the chemistry between Crosby and Fred Astaire is phenomenal. “White Christmas”, I think, like you said, it’s more vignettes. There’s like just… It’s like scenes and it kind of plods along. And so for me, when I watch “White Christmas”, I love the beginning of “White Christmas” where they sing “White Christmas” at the war. And then I like it at the end where they give the honors to their general, and it’s fantastic. The in-between stuff, I fast forward through that because I just felt like they were just putting that in there to fill a movie.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah, no, it definitely has that feeling to it. I agree.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It’s like that weird, like 1950s avant-garde kind of modern… Yeah. It’s just… I don’t care for it. Another Christmas song that we sing and cherish is “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” sung by Judy Garland in “Meet me in St. Louis”. “Meet me in St. Louis” is an interesting Christmas movie because it’s a movie about a family that goes through the seasons of a year and Christmas plays one part in that. But the song like that season is just… It’s a big part of the story. What’s interesting about “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is the original version that was written wasn’t the one that ended up in the movie. What’s the backstory on that song?

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah, the original version of the song began with the lines “Have yourself a merry little Christmas. It may be your last.” [laughter] So it’s quite a bit darker, quite a bit more downbeat. What happened was that the composer, Hugh Martin, he was trying to write a song for this scene where Judy Garland is trying to console Margaret O’Brien, who’s distraught at having to move from St. Louis to New York. And in that moment, she’s distraught over the fact that she can’t bring her snowman with her that she just made. And so she’s crying and they’re out the window and Judy Garland starts singing this song to her. And so Hugh Martin was having a really hard time coming up with something that would work. His songwriting partner, Ralph Blane, heard what he’d written so far and said, “No, you’re really onto something. This is a really good melody.

You need to keep working on it.” So Martin went back and he read the script again, and he thought about the melancholy of that moment, and the rest of the song and the words now just sort of came to him. And it was a beautiful melody, but everyone agreed it was like way too sad and downbeat, Judy Garland said, “I can’t sing this. If I sing this to Margaret O’Brien, the audience is gonna think I’m a monster.” So she asked him to change it and Blane said No and… [laughter] So this impasse went on for a couple of weeks and everyone was trying to convince Ralph Blane to change the lyrics. Finally, another actor in the film, Tom Drake, the story goes, sat down with Martin and said, stop being a stubborn idiot and just change the lyrics and for whatever reason that made him finally acquiesce.

And so he changed it to the version that we hear in the film. And the great irony is that even the version in the film is notable for how melancholy and downbeat it is in addition to being really beautiful. So it’s enough of being downbeat in order to get the point across and it injects honesty into the season because sadness and melancholy is part of the season. And so I think that’s the way this film speaks to the full spectrum of emotions that we link to the season. And also, I just wanna say, as you say, most of the movie is not set at Christmas time. It’s season by season and Christmas is the… Well, it’s not technically the last season of the movie, there’s a brief epilogue where it’s Spring again, but it’s really the culmination of the story. And it is on Christmas Eve that the family finally gets together and resolves this central problem, which is will they move to New York? And Leon Ames says, “I’ve changed my mind. I’m not gonna take the job. We’ll stay in St. Louis until we rot.” [laughter] my favorite line. And it’s a big moment of triumph and the family will stay together in St. Louis. And that’s what we wanted all along. And it took Christmas, which is the ultimate family day, arguably, to finally make it happen.

Brett McKay: Yeah, “Meet Me in St. Louis”, if you haven’t seen it. It is a fantastic film. I really enjoyed it. Judy Garland’s phenomenal in it. The trolley song, can’t beat that. It’s great. So we mentioned earlier that a lot of Christmas movies, they’re not box office hits, because basically if they’re released around Christmas time, they have maybe two months around that period to make money in theaters. There’s one exception to this trend, and that’s “Home Alone”. Everyone watches “Home Alone” every Christmas season. I think a lot of people forget how big of a phenomenon “Home Alone” was when it came out. So how big of a Box Office success was this movie?

Jeremy Arnold: Oh, it was enormous. It is still considered, or it still is the highest grossing live action comedy in the United States when adjusted for inflation. And that really says something, I mean, it opened in late November 1990, and it played into the summer of 1991.

Brett McKay: That’s crazy.

Jeremy Arnold: Which is like… That never happens anymore. It’s really astonishing how well it played. I was actually looking at the Weekly Box office tally on that not too long ago. And even like five or six months later, it was grossing over a million dollars every weekend, which is quite amazing. So I think the fact that “Die Hard” is… Not “Die Hard”, that “Home Alone” is still so popular, it shows another thing about what’s an important ingredient to making Christmas movies that endure. And that is to make a movie that appeals to all audiences, young and old. Back in the ’40s, most movies were made for all audiences and kids and grownups could all enjoy a lot of the same movies. And that changed at some point. And usually now it’s quite segmented. But the ones that really catch on, “Home Alone”, “Elf” is a great example too, young and old. We all love them and love going back to them as we grow older too.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and “Home Alone” almost didn’t get made. I think Warner Brothers was doing it, and then they’re making the movie, they wanted a budget increase, and they’re like, “No, we’re not going to do that.”

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah.

Brett McKay: And then Fox picked up the film, and that was a good move.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah, I think the budget increase was like $2 million or something like that. I think the budget was somewhere around $20 or a little less than $20. So it’s relatively minor, and it’s one of the great misjudgments in the entirety of Hollywood history because Fox came in, swooped it up and released it and made a mint. They just minted money with it. But in fairness, I don’t think anyone could have foreseen just how popular “Home Alone” would be.

Brett McKay: What do you think is the most Christmas-y scene in that movie? What’s the scene where you’re like, “Boy, I’m really, I’m feeling the holiday spirit.”

Jeremy Arnold: [chuckle] I’m almost reluctant to say this because it’s the same thing I said for It’s a Wonderful Life, but I would say the ending when, when the mother comes home and she’s quickly followed by the rest of the family, because that’s what Christmas is all about. It’s about families coming back together. Though I will say that I also love the sequence where Macaulay Culkin is decorating the house, putting up the holly and the tree and all that. It’s quite poignant because he’s all alone.

Brett McKay: What’s your take on Home Alone 2?

Jeremy Arnold: Not really a Christmas movie in the same way. I don’t think it really uses the season as meaningfully. It’s been a little while since I’ve seen it.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Jeremy Arnold: But that’s my take.

Brett McKay: And then we’re not going to talk about Home Alone 3 because that doesn’t exist.

Jeremy Arnold: No, that’s better left unsaid. By the way, I will add that Home Alone and Die Hard are very close to the same movie.

Brett McKay: Really? Oh man.

Jeremy Arnold: Very similar stories.

Brett McKay: I never thought about that. And yeah, I mean the Die Hard thing, you included that in the book. You think it’s a Christmas movie?

Jeremy Arnold: Oh, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Jeremy Arnold: I mean, it starts as the most common type of Christmas movie, which is a family trying to get together again to rectify their differences over the holidays. And John and Holly McClain are in the process of doing that when the terrorists take over and he has to spring into action. But a lot of his motivation is driven by his desire to fix things with his wife. But that’s not the only way it’s a Christmas movie. It also, in the music and lots of dialogue references, opening the vault is like opening a big Christmas present in a way, the way it’s presented. Ode to Joy is playing on the soundtrack, which is linked to the season. But the most vital thing I think is that Die Hard is violent, but it’s not unpleasant. It’s very joyful and cheerful. And that is probably linked to the season more than anything else about it. Home Alone, of course, has a lot of violence in it, but it’s cartoonishly joyful. So…

Brett McKay: All right. So yeah, Kevin McCallister is John McClain.

Jeremy Arnold: Right.

Brett McKay: I never thought, that’s a great, I like that.

Jeremy Arnold: John McClain is a kid. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So you mentioned Elf. That is our family’s favorite Christmas movie. In fact, we’re watching it right now, watching little bits of it each night. Elf’s got an interesting backstory because it came out in 2003, but the idea of Elf had been shopped around for a long time before that. So tell us the backstory of this movie.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah, it had been written in the early 1990s, so about 10 years before the movie opened. And it was written by David Berenbaum. And I have not ever read the original script, but what Jon Favreau has said was that it was much darker, much darker than the final movie. And why didn’t it get made until later? I don’t know. This is just the way of things in Hollywood. It’s not uncommon for scripts to take years, just sort of work their way through town until someone finally decides to make it. But Favreau got the original screenplay and read it, and he thought if I could soften this up, if I could warm this story up a bit and make it a PG movie rather than a PG-13 movie, that’s something I’d like to do. He was really driven, he said, by the fact that we’d just gone through 9/11, and he wanted to reclaim New York. He wanted New York to not just be thought of as the site of these horrible attacks, but to reclaim it for New Yorkers and for Americans in a more romantic, beautiful way. And so it’s sort of a love letter to the city as much as anything else. It was filmed a lot on location, although a lot in Vancouver as well, [laughter] to be honest. But that’s the way he approached it. And it’s actually, there are other Christmas movies that also started out as much darker scripts that were softened, and those are Die Hard and Gremlins, which are much lighter and more joyful than their original screenplays were.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And you mentioned in the book, originally, Elf was written with Jim Carrey in mind. But that’s hard to imagine. I could never see anyone else playing Buddy the Elf except for Will Ferrell. It’s like he was made for that part.

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah. And I could also see though that if the script were darker and edgier and more cynical.

Brett McKay: Yeah, okay.

Jeremy Arnold: I could see Jim Carrey being more appropriate to that version because he can get pretty dark.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Jeremy Arnold: At least in those days. It also… It was first offered to, well, not first, but just before Favreau came on, it was offered to Terry Zwigoff to direct, and he turned it down and decided to do Bad Santa instead, which came out a couple of weeks after Elf.

Brett McKay: What do you think the appeal is of this movie? Why are people still watching it 20 years later?

Jeremy Arnold: I just think it’s timeless. It’s timeless in the way that it was made more than anything. Favreau has spoken much of his conscious decision to make it in a sort of analog way. So no computer animation, but practical special effects, traditional stop motion for some scenes, the use of forced perspective to create the illusion of a grownup human at the North Pole with little elves. I think that it’s interesting if you compare it to The Polar Express, which came out a year or two later, that is so dated today because it uses this motion capture computer animation that has greatly been improved since then. Even when it came out, it didn’t really look that good. So when you go back to the tried and true practical technologies, there’s a charm and timelessness to them that really endures, I think. And he was influenced by the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, TV special in the ’60s, all of those ’60s Rankin/Bass films. He wanted to capture the spirit of those in Elf. I also think that Elf, as we talked about with Home Alone, it appeals to all audiences, young and old.

James Caan is a very Scrooge-like adult character. He transforms like Scrooge himself. Almost every Christmas movie has some kind of Scrooge-like transformation happening. And Zooey Deschanel also, I would say, undergoes a Christmas transformation. She doesn’t like Christmas at first, and by the end, she most certainly does.

Brett McKay: So Elf, and you can maybe say Love Actually, they seem like they were the last classic Christmas movies made, and that was 20 years ago. Both these movies were made in 2003. Do you think another Christmas classic could be made in the age of streaming?

Jeremy Arnold: I do, but it’ll be a lot harder. Our viewing habits are so segmented now. We’re so used to watching things alone at home on a TV or our computers. Going to the cinema is still, it may have shifted permanently because of the pandemic. I hope not. A lot of things have threatened theatrical movie-going over the decades, and it always endures. So there’s hope there from history. But, nonetheless, there are so many outlets to watch content on now, watch Christmas movies. I think the streaming Christmas movies, they’re their own genre. I don’t really see them in the same way as I see these theatrical Christmas movies. They’re not my cup of tea, but they do show that there’s still a great hunger for some kind of seasonal content, story to see during the holiday season. And I think the success of this year of Barbie and Oppenheimer, that proves that it is still possible for a theatrical movie to garner huge audiences. So if Barbie could do it, the right kind of Christmas movie could as well.

Brett McKay: Let’s say someone wants to watch a Christmas movie, but they’re tired of the popular standards. A Christmas Story, TBS is airing that 24/7, It’s a Wonderful Life, Elf, Home Alone. Is there a lesser known Christmas film you would recommend watching? So I think we mentioned a few, Holiday Inn. If you haven’t seen Holiday Inn, but you’ve seen White Christmas, I’d recommend checking out Holiday Inn. Two or three that you would recommend people checking out.

Jeremy Arnold: Sure. My number one recommendation would be Remember the Night, which is a 1940 release starring Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray. This is the first of four movies they made together. Their second would be Double Indemnity, a few years later, which is hard, cynical film noir. This is warm, poignant, romantic comedy drama. It’s a mixture written by the great Preston Sturges. And it’s about an assistant DA in New York, played by MacMurray, who’s prosecuting Barbara Stanwyck for shoplifting. And the trial gets postponed until after the holiday, until the new year. And when MacMurray realizes that Stanwyck is going to have to spend that time in prison, he bails her out and ends up driving her to her childhood home in Indiana, because he’s going to his own childhood home elsewhere in Indiana, and so decides to give her a lift. And when they get to her childhood home, the house is unforgettably presented. It’s dark, it’s cold. It’s the least inviting house in the history of movies.

And her mother is one of the iciest mothers in the history of movies. And she treats Stanwyck terribly and cruelly. And MacMurray sees this and immediately decides to take her to his own home for Christmas, which is a warm, light-filled, loving house with his mother and aunt and a cousin, I think. And so Stanwyck starts to see what a positive family Christmas can really be like. And this all helps them start to, of course, fall in love. So this is what makes it a great Christmas movie. It’s using the season to literally define the characters and create the story. This film could not really work as well if it were not set during the holiday season. And it’s also just so funny and romantic. People who see it fall in love with it. So I’d recommend that.

Brett McKay: One more you’d recommend?

Jeremy Arnold: Yeah. So I’m going to give one on the more curmudgeonly end of the spectrum for people who like that, and I’m one of them. I can’t decide which one to say. I’m going to mention both. The Man Who Came to Dinner is a 1942 satire, Monty Woolley, based on a great Broadway hit. And it’s about a literary critic who breaks his leg in a small Midwestern town and is confined to the home of a couple in this Midwestern town over the Christmas season, which he thinks it’s uncivilized and horrible, and he just wants to get back to his sophisticated New York. So he takes over the house, invites all his eccentric friends to come and visit, and it’s just a crazy farce. But it really speaks to something true about this season, which is the idea of a house guest who never leaves. I think we have all had guests who overstayed their welcome, and we have all been guests who overstayed their welcome at some point in our lives. And so that creates a lot of the comedy, and it’s just full of witty, acerbic, verbal barbs every five seconds. And the other curmudgeonly one, which really is under-known, is We’re No Angels, starring Humphrey Bogart, which was made in 1955.

And this is a black comedy about three escapees on Devil’s Island who plan to murder and rob a shopkeeper. But then when they realize his plight, that his brother is ruining his life and his business isn’t going well, they soften and they undergo a Scrooge-like transformation and then decide to help the family instead of killing them. And it’s all set during the season, and it’s very farcical, but also dark beneath the humor, which is very refreshing when we’re watching movies like Elf.

Brett McKay: Yes.

Jeremy Arnold: We want something to relieve that.

Brett McKay: Well, Jeremy, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about your work in the book?

Jeremy Arnold: They can find the book on Amazon and on the Hachette Book website. That’s the publisher, hachettebookgroup.com.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Jeremy Arnold, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure, and Merry Christmas.

Jeremy Arnold: Merry Christmas to you, Brett. It was great talking to you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Jeremy Arnold. He’s the author of the book, Christmas in the Movies. It’s available on amazon.com. Check out our show notes at aom.is/christmasmovies where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AoM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. And until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AoM Podcasts, but put what you’ve heard into action.