Testosterone. It’s what makes men, well, men. But my guest today argues that this hormone is a paradox. On the one hand, it makes men physically strong, courageous, and ambitious. But on the other hand, testosterone can contribute to prostate cancer, heart disease, and asocial aggression.

My guests’s name is Charles Ryan. He’s an oncologist that specializes in prostate cancer, and in his book, The Virility Paradox, he walks readers through the upsides and the downsides of testosterone. We begin our conversation discussing testosterone’s role in prostate cancer and how Charles artificially lowers T levels in cancer patients to prevent its growth. Charles then walks us through how our exposure to testosterone in the womb has a huge role in how we respond to testosterone later in life. We then delve into the positives and negatives of T, including the way it decreases the risk of Alzheimer’s but increases your chances of balding and can even inspire asocial aggression. We end our conversation discussing whether TRT is the fountain of youth for older men or can turn young guys into beasts.

Show Highlights

- How Dr. Ryan got started studying testosterone and its effects

- The ways in which testosterone depletion affects Dr. Ryan’s patients

- Signs of prostate enlargement

- Prostate cancer statistics and treatments

- What characteristics does testosterone drive (in both men and women)?

- The relationship between parenting and T levels

- Testosterone sensitivity and how every man reacts differently to it

- Fetal testosterone and how it impacts T levels throughout life

- 2D:4D ratios, and how that impacts one’s response to T

- Testosterone and a man’s sex drive

- What life is like on testosterone hormone therapy

- Falling in love, libido and sex, and T

- A surprising link between testosterone and Alzheimer’s disease

- Why does testosterone stimulate facial hair growth, but also balding?

- What’s with the onslaught of drugs that reduce balding? Are there dangers in taking them?

- The connection between asocial aggression and T, and the danger in connecting high T to criminality

- Testosterone’s negative effects; should men temper their biology?

- Older men with declining T and TRT (testosterone replacement therapy)

- Men in their 20s and 30s taking TRT for functionally “cosmetic” reasons

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- AoM series on testosterone, including how to naturally raise it

- How to Protect the Health of Your Sperm

- Master Your Testosterone

- How Testosterone Fuels the Drive for Status

- Do T-Boosting Supplements Really Work?

- The 2D:4D Ratio: What the Length of Your Ring Finger Says About Your T

- “The Abstinence” episode of Seinfeld

- Simon Baron-Cohen

- How to Grow a Beard

- Balding Gracefully: Tips and Hairstyle for Balding Men

- Getting Strong vs Getting Ripped

- Prostate Cancer Foundation

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Slow Mag. A daily magnesium supplement with magnesium chloride + calcium for proper muscle function. Visit SlowMag.com/manliness for more information.

Grasshopper. The entrepreneur’s phone system. Have a separate number that you can call and text from by going to grasshopper.com/manliness and get $20 off your first month.

The Black Tux. Online no-hassle tux rentals with free shipping. Get $20 off by visiting theblacktux.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Testosterone, it’s what makes men, well men. My guest today argues that this hormone is a paradox. On the one hand it makes men physically strong, courageous, and ambitious, but on the other hand testosterone can contribute to prostate cancer and asocial aggression. My guest name is Charles Ryan. He’s an oncologist that specializes in prostate cancer. In his book, the Virility Paradox, he walks readers through the upsides and the downsides of testosterone. We begin our conversation discussing testosterone’s role in prostate cancer growth, and how Charles artificially lowers T levels in cancer patients to prevent its growth. Charles then walks us through how our exposure to testosterone in the womb, yes when you were a fetus, has a huge role in how we respond to testosterone later on in life. We then delve into the positives and negatives of testosterone, including the way it decreases the risk of Alzheimer’s, but increases your chance of balding. We end our conversation discussing whether TRT is the fountain of youth for older men, or can turn young guys into beasts.

After the show is over, check out the show notes at aom.is/virility. Charles joins me now via clearcast.io. All right, Charles Ryan, welcome to the show.

Charles Ryan: Thank you. Happy to be here.

Brett McKay: You published a book called the Virility Paradox. Tell us about your background. What got you thinking about testosterone? It’s all about testosterone. What got you thinking about testosterone and wanting to write a book about it?

Charles Ryan: Yeah so I’m a medical oncologist, and I focus on the management of prostate cancer. Actually, I focus on two diseases, prostate cancer and testicular cancer. Both of them tend to involve testosterone, but most importantly prostate cancer is a disease that is driven by testosterone, and the management of it, for many patients if not most ultimately, is the depletion of testosterone in a way to sort of cut off the fuel supply to the cancer. Ultimately, this disease, in those who die of it, it becomes resistant to these effects and it figures out a way, the cancer does, to make its own testosterone, to be really sensitive to testosterone, so testosterone is all around prostate cancer. It’s really the central foundation, or the foundation of how we think about it and manage it.

Brett McKay: So I imagine as you’ve reduced testosterone in patients you’ve seen effects of that, like in their personality, things like that?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, absolutely. That’s one of the really interesting things as an oncologist in the management of cancer. This is really the only cancer, I guess ovarian and breast would be the others potentially, but more so prostate, this is the only cancer where to treat the cancer we have to deplete a chemical that is so fundamentally important to identity as testosterone is to the identity of a male. That’s something that we’ve done for a generation now, since the 1940s when it was first discovered that you could do this. Interestingly as I’ve been practicing medicine for many years now, I’ve had many people who have sort of worked in my clinic, or have met my patients, reflected almost jokingly your patients seem so nice in a way. I used to sort of joke back with them and say of course they’re nice, of course these men are nice, they have no testosterone. Which is not always the case of course, but that sort of joke in a way, or that observation, percolated within me over the course of many years and I actually began to think maybe there’s actually something to this.

So I started researching it, and I started gaining an appreciation for all of the other factors, things that testosterone does to our bodies and our brains, and ultimately to our society. That was the genesis of starting to write the book. Once it hit me, I started digging in to the research on it outside of the world of prostate cancer and really began to realize that this chemical, this hormone, has lots of roles in our world.

Brett McKay: Before we get into those roles testosterone plays, and not only in the individual but into society, I’m curious about this link between testosterone and prostate cancer. I guess without getting too technical and complex, why is it that testosterone drives prostate cancer?

Charles Ryan: Sure. It’s actually pretty simple. The prostate is an organ that is involved in reproduction. It’s a reproductive organ. It doesn’t’ really develop until puberty. It develops during puberty because of the rise of testosterone. The prostate’s normal function in life is to create some of the fluids that are in semen, that protect sperm and allow us to reproduce. It’s every bit linked to our fertility and to reproduction, and it comes to life, so to speak, at puberty and is driven by testosterone. A lot of people, a lot of men as they age get enlargement of the prostate, but not prostate cancer. That in a way is also driven by long term stimulation from testosterone. It makes sense then, if you think about cancer, that a cancer that arises from this organ that is driven by testosterone would itself be driven by testosterone. That is in fact the case, and has been known for 80 years.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the enlargement of the prostate, that’s something that if you have to get up a lot to go to the bathroom, that’s one of the signs your prostate might be enlarged.

Charles Ryan: Right. A lot of men as they age their prostate gets big. What happens is it … The prostate sits, by the way, right at the base of the bladder, so when the bladder is emptying when you’re urinating, if the prostate’s big, that process stops early and so the bladder doesn’t empty. So you have to go to the bathroom more often. That’s what’s a common condition called benign prostetic hypertrophy, or BPH, but it’s a really common reason why men have to get up at night to pee. That begins at different ages in men, but frequently as early as age 35 or 40 even people start to have that phenomenon.

Brett McKay: Right. I’ve heard, I don’t know if this is true, but like if a man lives long enough, you’re probably going to get prostate cancer. I mean it’s like a disease of old age basically that is almost inevitable.

Charles Ryan: Yeah it is an age related disease. Now there’s a couple points there. I think that your statement is largely true. I’ve heard that ever since I started studying medicine as well. The epidemiologic data say that about one in six American men will get prostate cancer. A lot of men will get prostate cancer that is not that aggressive. It’s a cancer interestingly that doesn’t almost need treatment. That’s interesting, but the other thing about it is, getting back to the testosterone idea, is that this is a cancer that is again being driven by the chronic persistent stimulation from testosterone. The longer we get, if we have testosterone in our bodies, that may increase the likelihood of this occurring.

Brett McKay: Okay, and we’ll talk about that later on when we talk about TRT because we’ll discuss, I want to discuss that a bit. Let’s talk about, let’s move away from prostates, and just sort of what are some of the attributes that we know that testosterone drives in men, but also women too?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, so we can think about this in sort of both the positive and the negative way, which is that I attribute, I credit testosterone with a lot of really great things in life, such as our ability to be strong, our ability to navigate space, to defend ourselves, and I’m going way back now even in our evolution, to hunt, to fight off aggressors, to be aggressors, in so far as that can be a good thing, and to explore the world. I mean I think that that’s a pretty well known anthropologic phenomenon that this chemical and other processes have helped create our ability to build the beautiful world that we have and survive the aggressors that we’ve faced. That’s a sort of a positive way to look at it.

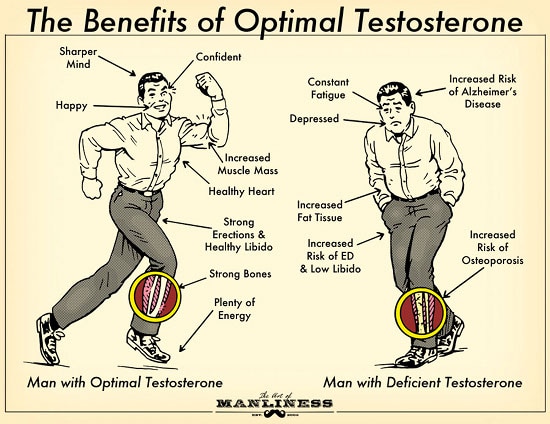

Testosterone can keep our bodies fit, not only muscular, lean, by reducing fat in our bodies. It can also help with certain aspects of cognition, even memory and other aspects of how we think. There’s a lot of evidence to show, and we know this from treating prostate cancer by taking testosterone away, that testosterone may help prevent things like diabetes and muscle loss, or sorry bone loss, bone thinning rather, and other aspects like that. It’s no question in my mind that testosterone is an important part of health, both for men and women. Mostly for men because the quantities in men are about 10 times higher than they are in women, but that’s, and that’s a topic of conversation in the book.

The other issue around testosterone and what it does to health is of course it drives reproduction, drives libido, drives, like I said, the prostate and keeps the reproductive organs going. It’s really sort of one of the fuels of the reproductive system. Without testosterone, the world, as I say in the book somewhere I think, the world would be a lot less exciting place, and in fact we probably wouldn’t have evolved to the point where we are today.

Brett McKay: What about the negatives?

Charles Ryan: The negatives are things that a lot of it comes from some experimental psychology and other aspects. Some of this might be intuitive to the listeners. Too much testosterone, too much aggression could be a problem. I write a chapter and mention very frequently empathy, for example, and lack of ability to sense the emotions in others. Giving testosterone to research subjects has been shown to reduce their sensitivity to the emotions of others. It’s been shown to sort of reduce moral ambiguity, like people are willing and able to make decisions that may be difficult decisions, like hurting others or killing others even in experimental models. In the book I also talk, I try to bring it in to sort of the modern world and talk about how we’re not out there all hunting for our food and fighting wars everyday, but things like higher testosterone levels in men whose partner has recently given birth is associated with a decreased level of attentiveness to the newborn.

There has been studies, and I cite one of them in the book, responsiveness to a crying infant. You can actually measure brain activity when a crying infant is in your midst. The researchers have shown that higher testosterone activity reduces or delays the responsiveness of this. This gets in a little bit to the empathy idea and our ability to connect with the emotional state of others. But also, as I think is important and it’s fairly consistent, research shows that our parenting and our parental involvement is related to testosterone. Men with higher testosterone levels even have been shown to spend less time with their kids. There is a higher rate of divorce and marital strife and relationship problems in men with higher testosterone. Those are behavioral things related to higher levels of testosterone.

In terms of physical health related to higher levels of testosterone, what we get on that level has to do mostly with what we learn from people who are taking anabolic steroids, which is not exactly taking testosterone, but it’s taking chemicals with a testosterone like activity. We know that there can be problems associated with the heart, problems associated with potentially even affecting bone health in a negative way in certain circumstances. That’s something that is slightly related to the natural levels of testosterone, but really comes at the extremes.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s the virility paradox. There’s both these positives and negatives that come with it.

Charles Ryan: Right.

Brett McKay: Okay well let’s talk about this, sort of get into, starting from the beginning, from when you’re a fetus and how testosterone affects you. Well let’s talk about this, testosterone sensitivity. A lot of people think if you just jack up your testosterone levels it’s going to have all these amazing effects on you, but as you talk about in the book, some people are more sensitive to testosterone. Why is that?

Charles Ryan: I think this is probably the most important teachable moment, teachable issue I’d like to get across related to testosterone, which is it’s not a one size fits all thing. There are really three components that I term the virility triad that have to do with how sensitive we are to testosterone. We talk about testosterone levels as if that’s all that really matters, but the other thing is fetal testosterone, which is how much you’re exposed to before you’re born. Then the other thing, I’ll come back to that, the other thing is the anogen receptor, which is the sensitivity of this receptor in all of these cells to the testosterone that’s there. It’s like a trigger. It’s got a certain level of sensitivity.

But with regards to the fetal testosterone, I found this to be really fascinating, and frankly this is not something I knew in my line of work, that when we are in about our week 15 of gestation, so I guess that’s towards the end of first trimester and middle trimester, where testosterone levels spike in a fetus, in both male and female fetuses, but it does across a whole spectrum. When this occurs, the brain is undergoing obviously a ton of development during fetal life, and the higher the fetal testosterone, the more there may be traits associated to what we might assert would be related to testosterone later on in life. This has been studied by both looking at levels of testosterone in the amniotic fluid, and then traits in the babies that were subsequently born from those women, which is really interesting.

Then also there’s a phenomenon where this thing called a 2D to 4D ratio. If you look, your second digit, which is 2D, is your index finger, and your fourth digit is your ring finger. If you hold up your right hand and you look at the ratio of how long your ring finger is to your index finger, that ratio is roughly proportional to the amount of testosterone that you were exposed to as a fetus. That’s because there are anogen receptors in our fingertips, crazily enough. If your ring finger is a lot longer than your index finger, that’s actually a low ratio, like .75, or .8, or something like that as opposed to .99. That’s higher testosterone in fetal life. That simple observation launched a lot of interesting research in behavioral science, if you will.

One that I cite in the paper is really interesting. A researcher named Coates in the UK looked at this factor, 2D to 4D ratio, in day traders in the London Stock Exchange and found that the income, the bonus of the day traders was directly proportional, after correcting for a lot of other factors, to their 2D to 4D ratio. The implication was that day trading is a gamble in a way, it’s a risk taking behavior, and it requires sort of setting aside doubt and moving forward and making these kinds of snap decisions. I love this paper. It was in a very respected journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, where they showed the yearly bonus of those with the highest fourth, the highest quartile, of the 2D to 4D ratio was like 10 times to that of the yearly bonus of those in the lowest, even after they corrected for the years of trading experience. What this says is that testosterone may have affected the brains of these individuals most well before they were born. This is says nothing of their actual testosterone levels in their blood, so a fascinating area.

This has been studied with respect, women have the same effect, and it drives the sensitivity to testosterone. If you give testosterone to somebody then you measure their behavior or whatever after that, people who have different levels of this prenatal testosterone will respond differently to the testosterone that you give them. That’s kind of the idea that there’s this altered, that there’s this spectrum of sensitivity to what the levels of our blood testosterone do to our body.

Brett McKay: So if you have the longer ring finger, you respond better to testosterone?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, it’s actually in some cases the opposite because you’re not, you’re more malleable by exogenous testosterone, is one way to think about. There’s research going in a lot of different directions, but yeah I think of the prenatal testosterone, from what I was able to gather from it, as a driver of how malleable we are by testosterone levels throughout life. One of the things we don’t know, which is interesting, is, for example in my world of prostate cancer, it has been shown that the longer ring to index finger ratio is associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer, which kind of makes some sense maybe. But what we don’t know is whether that matters in terms of the survival of the people, and whether the cancer is more aggressive or whatever based on that. So we’re studying that.

Brett McKay: Do they know why some fetuses are exposed to more testosterone than others?

Charles Ryan: It’s genetic really, has to do with the genetics of probably both parents. It’s not something that’s related too much to diet or health of the mother, although one could imagine a setting where the mother is in a health impaired situation that the testosterone level could be lower. There have been some speculation about diurnal rhythms and seasons of the year, for example, because testosterone does undergo a little bit of a rhythm with daylight and darkness, but that’s not really been substantiated to the point where I think that it’s completely known.

Brett McKay: Okay so you talk about some of the attributes. If you’re exposed to high levels of testosterone in the womb, you’re probably going to show more what we call masculine traits, risk taking, that sort of lack of empathy, et cetera.

Charles Ryan: Fair. Yeah, that’s a decent way to put it.

Brett McKay: Okay. Let’s talk about, I mean I think we all intuitively know what happens if you have high testosterone. We probably have met those guys. They’re just, I don’t know, they’re manly right.

Charles Ryan: Yup.

Brett McKay: But what happens, we’ve talked about this a bit, but what happens when you artificially decrease their testosterone with prostate cancer treatment? Do they just become these big teddy bears? What happens? What goes on there?

Charles Ryan: Well, some do. This is what’s, this is why I got interested in this topic, which is that, and this is basically what I do in my clinic. The patients I’m treating, many of them have had suppressed testosterone for many many years. They do that because it controls the cancer. Now there are some individuals who will say to me, when I have this conversation with them, look I need to use hormonal therapy, which is what we call it, against your prostate cancer. They will refuse at first. Some of them will refuse the whole time because they will fear so much the loss of their testosterone, or they will hear that it’s so awful that they will do everything that they can to avoid it.

For some of them, they’re right to think that way because when they undergo this depletion they really suffer, others not so much. That’s what I find to be interesting is that others actually either don’t have much in the way of side effects. The other phenomenon, which I find really fascinating and I write about in the book, is there are others who feel like it’s actually helpful to them when their testosterone goes away. For example, I’ll have some people who will say, “I used to think about sex all the time. It was part of my daily stream of thought, every minute on some level, and all of a sudden that’s not there anymore. And I don’t mind that because it’s almost like I’ve freed up more mental space for other things.” I think that this is an issue that some people face. I mean healthy libido is a great thing, but I think there are some people who have, maybe have a little too much, and that they appreciate it when it comes down.

I have this quote in the book from Plato’s Republic, a book written over 2,000 years ago in which they talk about this phenomenon of as you get older and you lose your libido or your desire to be with a woman, it actually opens up other parts of your psyche. It opens up other parts of your mind. As Plato puts it, “it allows for the emergence of character.” Once I saw that quote, I thought wow this is something that is so fundamental to human philosophy and psychology that Plato was writing about it. I see this whole spectrum in my patients, and it’s not a one size fits all treatment. With all of that said, I would never say to a patient you’re going to feel better after we take away your testosterone because you’re not going to have a libido. That’s not what I’m saying because it’s really troubling for a lot of people.

From a physical perspective, just incidentally, the signs and symptoms of low testosterone in my patients are also what you might see in patients who are not getting their testosterone depleted, but it’s just going down naturally. Fatigue, loss of energy, loss of muscle mass, hot flashes can occur, and of course loss of libido. Getting back to your teddy bear comment, I would have to say that I actually do think that some people kind of do become big teddy bears, and that’s what part of the fun, or the joy of treating these patients. Sometimes they kind of realize that hey you know, I’m in my late 60s, and my testosterone’s gone, and it kind of changes them a little bit away. Many of them are wonderful people to begin with, and become maybe softer and more empathetic as time goes on. I try to write about that in some cases in my book as well.

Brett McKay: Again, this is not one size fits all. People are going to respond differently right?

Charles Ryan: Absolutely. Right.

Brett McKay: That thing about you don’t think about sex all the time, and it opens up a new life to you, it reminds me of that Seinfeld episode where George Castanza stops having sex and he becomes really like a genius.

Charles Ryan: Yes! I wish I had had that idea, would have been a good anecdote for the book, but yes.

Brett McKay: When you reduce testosterone artificially in your patients, is this a permanent thing, or is it temporary?

Charles Ryan: It’s temporary. We have shots that we give. We can give it to last for one month, for three months, that kind of thing. Rarely, and historically what was done is if you remove the testicles obviously that’s permanent, but we do it temporary for some patients. There might be somebody, for example, who’s going to get let’s say radiation treatment for their prostate, and they might take the hormone therapy for a year or two years. Aaron, the character or the patient who I profile in the book, he gets a year of hormone therapy because we want to slow down the rise of his PSA. His story is really his one year on hormone therapy, and his adjustment to sort of life as a trial attorney, and thinking how’s this going to, is this going to take away my edge, and what it does to him, and things like that. That’s a pretty typical scenario. Now, in men with more aggressive prostate cancers or more advanced disease, many of them will ultimately need to have permanent hormonal depletion.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. Let’s get into some of these fun, I don’t know, explorations of testosterone and how they affect us personally. You talk about testosterone levels when men and women fall in love. What happens there and is there a difference between the two?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, so I try to make a distinction between falling in love and libido and sex because they’re kind of different things. Libido and sex is driven a lot by testosterone, it’s that drive to perform sex, if you will. Falling in love is different in so far as it’s more of a settling in. There’s a chemical known as oxytocin, which is really the opposite of testosterone. You’ll sometimes hear oxytocin called the cuddle chemical. If you give oxytocin to a man, it will make him more physically affectionate, but not necessarily in a sexual way. When falling in love occurs, testosterone may in fact sort of go down a little bit, and oxytocin may sort of drive it. That also what happens for example when your partner has a child and you’re getting more into sort of parenting mode, or nurturing mode is what I call it. That’s not a testosterone driven thing.

What’s really interesting is I write a little bit, and there’s a lot of science and controversy around autism because there’s a link, or I should say an association between higher levels of this fetal testosterone that we were talking about before and traits that we might think of as autistic traits, behavioral traits. Again, a little bit of a generalization, but not expressing empathy, not expressing emotion, focusing on detailed things as opposed to understanding the emotions of people around you, et cetera. That has been linked to high prenatal testosterone. But what’s interesting is that there’s sort of this theory that autism is kind of excessive male brain. It’s called the Excessive Male Brain Theory, EMB. In the treatment of autism now, they’re studying giving oxytocin. They’re studying giving the opposite of testosterone in a way to see if they can improve affection, and empathy, and those types of things. These two chemicals kind of go yin and yang.

In the book I write about a patient of mine who, a very dear patient who was widowed, had to go on hormonal therapy, was trying to meet women, and date women, and ultimately decided that he wanted to come off of all of his treatment because he wanted to be able to meet a woman. Ultimately what we discovered, or he discovered, is that falling in love can happen even when testosterone is low. I think that that’s the key thing is that I wouldn’t want people to think that libido, and testosterone, and virility, and falling in love are all wrapped up in the same thing because they’re kind of different.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that extreme male brain theory, Borat’s cousin is the guy that came up with that.

Charles Ryan: Yeah. I’m sure he would love to hear you call him that. He’s actually very well respected-

Brett McKay: He’s a genius, yeah. He’s really smart. He’s very well respected.

Charles Ryan: Yeah, I mean he’s a professor at Cambridge University. He’s doing a lot of really important work, not only in autism, but just in sort of the acceptance of autistic people, and inclusion, and things like that. He seems like a fascinating person. I’ve communicated with him by email about my book and things, and I told him about some of my observations. I actually wondered out loud to him why nobody has really looked at using the kinds of drugs that we use for prostate cancer in people with autism, right because we block testosterone. If autism is an extreme male brain, maybe there would be some benefits. Who knows.

Brett McKay: Right. Let’s talk about, I thought this chapter was interesting about testosterone’s connection to Alzheimer’s disease. What is that connection?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, so it’s, this science is still evolving, but there have been observations that men who have prostate cancer who live a long time with low testosterone have a higher, potentially higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease. We clearly know that there are cognitive effects, even in the short run, from the hormone therapy that we give. We hypothesize that there is sort of a spectrum, so maybe there are men who are at risk for cognitive problems in the short run from hormone therapy, and maybe that’s going to lead to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease for them. But the reality is, what’s really interesting, is that forget about prostate cancer for a second, is that the brain cells are happier in the dish, if you grow them in a lab for example, they’re happier if there’s testosterone in the mix. If you take testosterone away, they get thinner, they get less protected, and they’re more likely to become damaged. That’s one component of it.

Then also research has shown that if you look at testosterone levels in the brain between the ages of 50 and 80, testosterone levels in the brain go way down, like by 80%. So some theory that when we lose this, as we naturally lose this protection of brain testosterone, the neurons may in fact become damaged, and that may lead to some impairments. Now Alzheimer’s disease is a pretty specific entity where there’s an accumulation of proteins in the brain called amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These are things that accumulate. You can, if you do an autopsy on somebody who had Alzheimer’s disease, you can actually see these sort of actual plaques in the brain. There is a way that our … The plaques are really the accumulation of protein garbage in our brain, and testosterone will stimulate the break down of some of this garbage. It’s almost like, if you will, testosterone helps our brain cells take our their garbage. When testosterone is low, the garbage accumulates and it forms these plaques, and that’s what Alzheimer’s disease is. Now that’s a gross oversimplification of course, but there is a connection.

Brett McKay: Let’s move outside the brain to the cranium, the thing that encases our head. Testosterone has been connected with balding. Why is that? Testosterone stimulates facial hair growth so you think it would stimulate growth on the hair on your head, but it doesn’t. What’s going on there?

Charles Ryan: And there’s the paradox right. It stimulates growth of the beard and stimulates loss of hair on top of the head, exactly. Baldness is really interesting, not only for its connection to testosterone, but it is connected to some other health phenomena. Long story is that chronic exposure to testosterone, which is by the way converted into a chemical called DHT, which many people may have heard of, dihydrotestosterone. DHT stimulation on the follicles of the hair on a scalp will cause a thickening of the follicle. It will basically, if you think about the tunnel that the hair grows out of, that tunnel thickens. The hair thins, and ultimately that thinning hair goes away. That’s again a sign of chronic testosterone exposure, the health issues that it’s linked to for example. Baldness is a sign of a chronic testosterone exposure as is potentially heart disease and prostate cancer as I mentioned.

A couple of years ago there was an observation made that men who are losing their hair at 45 on the top of their head, not a receding hair line, but the middle, back of the head, they were at higher risk for prostate cancer, for high risk prostate cancer. This is a sign of sort of the testosterone role in our bodies. On the beard it’s totally the opposite, which is that it stimulates hair growth and it doesn’t stimulate the thinning out of those follicles.

Brett McKay: I think the same goes for nose and ear hair as well right? It keeps stimulating that growth. That’s why when you get older you get these bushes growing out of your ears.

Charles Ryan: Yeah. I hadn’t really delved into the science of nose hair that much. Maybe that will be in the second book because I’m sure we’d all like to see that chapter.

Brett McKay: Right.

Charles Ryan: But yeah, basically you’re right, facial hair, whether it’s on the ear or the nose.

Brett McKay: In the past few years there’s been this uptick I’ve seen, maybe just this psst year, there’s this uptick in companies selling pharmaceuticals that can reduce balding. You take these drugs. It’s not supposed to grow your hair back, it’s just supposed to slow it down. Do you know what’s going on there, what those pharmaceuticals do? And are there any dangers to those?

Charles Ryan: Yeah. A lot of those pharmaceuticals try to block the very effective testosterone on the hair follicle. There’s one that I highlight in the book called Propecia, which is very commonly used. Propecia is a drug, it’s the same drug that we use to slow the enlargement of the prostate, except at a lower dose. It blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, and therefore reduces the amount of testosterone that’s stimulating the hair follicle basically. Now getting back to this issue of the sensitivity to testosterone that we talked about before, there are many men, in fact there’s a foundation out there following men who took Propecia for hair loss who experienced in some cases irreversible loss of libido, irreversible sexual dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, and things like that. Indicating that some young men, and these are all men in their 20s and early 30s, some young men are extremely sensitive to these types of pharmaceuticals, so there’s definitely a danger to them.

Then there’s other, there are more benign things like there are shampoos that are designed to basically wash the testosterone out of the hair. I’ve actually used one of those for years, and I think it actually works, but it doesn’t penetrate into the system. It’s not getting into the blood and causing behavioral effects, at least as far as I know.

Brett McKay: Let’s get into sort of how testosterone affects us individually, but which ends up affecting us socially, the connection between testosterone and social aggression. This is kind of a paradox because there are some men who have higher levels of T, I think they’ve done studies where they show criminals typically have higher levels of testosterone than non-criminals, but there are some men with high levels of testosterone and they’re functioning, pro-social members of society. Why is that paradox there?

Charles Ryan: I would say that the science of criminality if you will, like that’s trying to link testosterone and criminal behavior, is kind of dangerous territory to be honest with you. There’s probably an association, but this is a great example to use the phrase association is not causation. For example, and we haven’t talked about this much, the androgen receptor, which is basically if you think of testosterone as the key, the androgen receptor is the lock into which the key goes. Any of our body tissues that respond to testosterone, whether it’s our muscles, or our brains, or our prostates, or whatever, have lots of androgen receptors in them. Your androgen receptors are not a monolith either. You can have an individual genetically may have fast androgen receptors, or may have slow androgen receptors. In fact, there’s a condition of very very slow androgen receptors called Kennedy’s Disease where they don’t develop muscles, and they don’t develop secondary sex characteristics, et cetera.

Anyway, I give this introduction to say that there was a study that I cite in the book that was done in India where they looked at individuals in prisons in India. They looked at controls who were not in prisons. They looked at people who had committed rape, they looked at people who had committed murder, and they looked at people who had committed rape and murder together, like violent rapists. I should say, I guess all rapists are violent, but I should say rapists who murdered their victims. What they found was that as they looked at this number, it’s called the CAG Repeat, it’s a molecular number, the lower the number the faster the androgen receptor. As they looked at the more violent the crimes were, they found that the androgen receptors were more active in those subjects, in those prisoners, compared to controls. They found a statistical significant association between that.

Now that does not mean that having a fast androgen receptor is going to make you a rapist or a murdered. It just is probably one ingredient in a very complex sociological and biological mixture that led to a violent act occurring. Now having a fast androgen receptor might make you a better athlete. It might make you stronger, or be able to jump higher, or do something else, or it might make you a better architect. There’s all kinds of ways that these things could have a beneficial effect. The science of criminology based on hormone levels is, as I looked at it I said wow this is kind of weak science, but it’s also just kind of interesting too. But I really try to make the point that this is association and not causation.

Brett McKay: Right, so I guess this is where environment would come in, on whether or not testosterone-

Charles Ryan: Absolutely.

Brett McKay: Like high testosterone, or high androgen receptor sensitivity is either going to be positive or negative.

Charles Ryan: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, and also this is I think one of the overarching themes of the book, which is we’ve got this paradox, which is that testosterone and this whole system of virility has gotten us to this point in our evolution. We’re good hunters. We’re able to survive. We create cities and societies, and maybe testosterone helps that. But it doesn’t always help it, and maybe this virility that got you to this point in our evolution is not quite needed so much anymore. I begin to ask the question of, knowing this and seeing this, are we in a position as men, or as a species really, to sort of temper this biology. In other words, we’re now able to control our environment. We are able to control so much of the natural world.

We now have a recognition of this paradox of virility I think, but are we able to control it. When we think about empathy and we think about behavior, and really more importantly when we think about nurturing and parenting, and being just good people, and we think about how some of our impulses that are built into our biology through our evolution may make us not so good people. I wonder if understanding that, understanding this paradox of virility might allow us to think about how we act and behave in certain circumstances, and actually ask ourselves from time to time is this the right thing to do or is this my testosterone acting.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about TRT. I’m sure people who are listening, they’ve probably seen the commercials or the billboards, getmyerectionback.com, lowlibido.com, whatever. You have all these men who are in their 50s, late 40s, 50s, 60s, who naturally would have their testosterone levels would have gone, but now they’re starting to take TRT. How is that changing your job as an oncologist?

Charles Ryan: Yeah, it’s not changing my job that much, although I do occasionally run into patients who were diagnosed with prostate cancer after they started TRT. That is probably because of carelessness on the part of their physician to not screen them for prostate cancer before they started testosterone, but it’s also just an inherent risk of taking testosterone, that you might wake up a sleeping cancer. But I think in the bigger picture just in terms of healthcare, there’s a couple points I look at. I say TRT is great for some men. Some men really benefit from it and I think it’s good to have it there for some men. It gives them a sense, it helps them to reduce body fat for example, maybe have more energy, and certainly help boost libido. When one looks at the studies in which you have a control group and a TRT group, the studies seem to suggest that there are benefits, but they tend to be early, and they tend to not persist beyond much of a year or so.

The major variable that I write about in the book is a variable called vitality, which is a mixed outcome if you will from a clinical intervention that has to do with energy and sort of activity of daily living type of things, and enjoyment of these things. Vitality spikes a little bit when you start testosterone replacement therapy, but by a year it’s back down to essentially the same levels as on a placebo. But I would say that shouldn’t dissuade somebody from considering it if they think it may be of benefit to them and their doctor agrees because there’s a spectrum. Some will benefit a lot, and some will benefit not so much. I guess I would just say that for those who don’t benefit so much it’s because of other things, or it may be because of just variability to which their body responds to testosterone, which is really the subject of the book because of the androgen receptor and because of the fetal testosterone and things like that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think a lot of younger guys are interested in TRT because they’re thinking well I might not have clinically low testosterone, but it’s on the lower end. If I can jack it up to over 1,000, I’ll become this super beast, and that might not be the case. At a certain point you might have enough testosterone and your body is just like well we’re not going to do anything extra with this extra testosterone you’ve given us.

Charles Ryan: Yeah. Actually, good point by the way. I was referring to older men who have a declining testosterone who take TRT. Then there’s the younger men, men in their 20s and 30s, who are taking it because of, let’s just call them cosmetic reasons, or other things. There it’s not studied as much because what you have in those settings is you have a selection bias because of the data that are published on the use of testosterone are coming from gyms and places like that where people are highly motivated. That’s different from being a 75 year old man with a declining testosterone and being on a placebo controlled trial where you get data with a control arm. But I guess the point remains the same. The effect that it has on the subject, the man, varies based on their individual biology. I think that that’s a key point to make at any age.

Brett McKay: Well Charles this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work.

Charles Ryan: The book is available online, on Amazon. It’s actually published also by Ben Bella Books, and you can buy it directly from their website. It’s also available on Audible.com, and hopefully your local bookstore, which would be good for you and the bookstore. My work focuses on prostate cancer. That’s my academic side. Men interested in learning more about prostate cancer I would turn them to The Prostate Cancer Foundation, which is a great website, as well as your standard websites like Medscape and those others that might have information for them on prostate cancer risk, and prevention strategies, and detection.

Brett McKay: Awesome. Well Charles Ryan, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Charles Ryan: Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Charles Ryan. He’s the author of the book the Virility Paradox, available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/virility where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed this show, please give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. As always, thank you for your continuing support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.