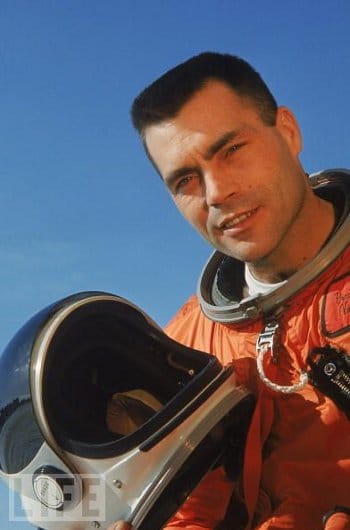

On August 16, 1960, Joseph Kittinger parachuted from nearly 20 miles above the earth’s surface.

What drives a man to jump from space?

Scientific discovery certainly. The jump represented more than a daredevil’s thrill or a desire to break records; this was nascent space travel, the world’s first manned space program. Kittinger’s work with Projects Manhigh and Excelsior would study the physiological effects of space on a human subject and test the communications and logistics systems needed for sending a man on high. Before Project Mercury, before even the monkeys were launched into orbit, Joseph Kittinger would travel to the top of the world.

But it was more than that. It was manliness at work. The pioneering spirit. The explorer’s courage. The desire to go farther and higher, simply to see what is out there and what man is capable of. The need to push the limits of what is possible.

Stories like Kittinger’s make me feel something electric in my bones. They inspire me to push myself as a man. That’s why in this two-part series I’ll be profiling the stories of a couple of amazing “pre-astronauts.” Today we start with Kittinger.

Project Manhigh

“Everything good that had happened during my life had come from volunteering.”

Joseph Kittinger, a fighter and test pilot for the Air Force, adhered to a personal rule: always volunteer for whatever assignment came up. It didn’t matter how little information he had about a potential opportunity, he was game to try it.

So in 1953, while testing planes at Holloman Air Force base in New Mexico, when he heard that a Colonel John Paul Stapp was looking for someone to help with experiments in zero-gravity, he didn’t hesitate to sign up. He was the only pilot there to do so.

Stapp initially had Kittinger flying planes in large parabolic arcs, giving the researchers on board a small window in which to experience and study weightlessness.

Stapp’s next experiment was to send a manned balloon to record heights-deep into the earth’s stratosphere. This was Project Manhigh, and Stapp needed a pilot to take the balloon on its maiden voyage, to test how the capsule, and the man, would handle being above 99% of the earth’s atmosphere. Kittinger volunteered.

Manhigh I

The Manhigh test flight lifted off on June 2, 1957. Kittinger, floating inside a pressurized gondola, would soar 24,000 feet higher than any balloon had ever gone.

But the flight was not without problems. The radio communication failed; Kittinger could hear the ground crew, but they couldn’t hear him. He therefore had to use Morse code to relay his messages. Then, less than an hour into the flight, a more critical problem was discovered. The hose that was supposed to be venting the oxygen into the capsule was venting it out. Half of Kittinger’s O2 was already gone. But he refused to abort the mission, figuring he’d just have to carefully ration the oxygen and hopefully squeak by with just enough.

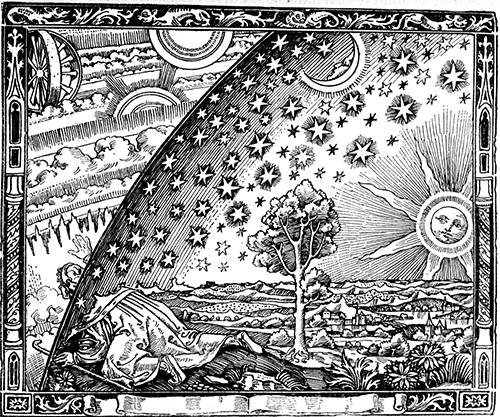

His balloon lifted through the clouds, the warm troposphere, the violent buffetings of the jetstream and finally into the hostile vacuum of the stratosphere. The sky above him turned from baby blue to indigo to an indescribable inky darkness. Above him stretched the infinity of outer space, below him rested the curvature of the earth.

When the balloon reached 96,000 feet, only enough oxygen to make it safely back to earth remained, and Kittinger was ordered to begin his descent. C-O-M-E-U-P-A-N-D-G-E-T-M-E Kittinger tapped out in response. The ground crew panicked, worried their pilot was experiencing “breakaway phenomenon,” a supposed hallucinatory state where a pilot lost touch with reality and disconnected from the ground. But Kittinger was simply having some fun and had in reality already begun to descend. He landed without an atom of oxygen to spare.

The Manhigh test flight had been a success. Other pilots would take two more flights in the balloon, eventually reaching 101,500 feet. But Kittinger’s next project would involve not only rising into space, but leaping from it.

Project Excelsior

In 1958 Col. Stapp asked Kittinger to come to the Aero Med Lab at Wright-Patterson in Dayton to work on their program for improving emergency escapes. Kittinger spearheaded a project to solve the problems associated with high-altitude parachute jumps. Parachutists could lose control and get stuck in a dangerous “flat-spin,” spinning to earth at an ever accelerating speed. Flat spins had been clocked at up to 200 revolutions a minute, fast enough to dislodge a man’s brain and scramble his organs. The solution Kittinger and his team came up with was a multistage parachute system-three parachutes opened automatically at different times to stabilize the man in freefall. Would the system work for pilots ejecting far above the earth, hurtling at near supersonic speeds? Kittinger volunteered to find out.

Excelsior I

“Stapp once told me to think of it as being enveloped in cyanide. You were essentially swimming in an invisible poison that would kill you in seconds. If the suit were cut open, there would be no contingency. You’d have less than ten seconds of useful consciousness. It didn’t matter how smart you were, how well-prepared you were, how tough you were. You were simply dead.”

Unlike the closed, pressurized capsule used in project Manhigh, Kittinger would now be traveling in an open gondola. The only thing protecting him from the deadly stratosphere would be his pressurized suit. If the suit should rip or his helmet’s visor open, in a matter of seconds his saliva would boil, the fluid in his body would begin to evaporate, interior gases would expand and grotesquely swell his body, water vapor would fill his lungs, and his blood vessels would burst. Not a pretty way to go.

Excelsior’s first flight lifted off on Nov. 15, 1959 from Truth and Consequences, New Mexico. It did not go smoothly. Solar glare blinded Kittinger for much of the way up, his helmet felt like it was about to pop off, and condensation fogged his visor. But things would get really hairy during his jump. Leaping from 76,000 feet, his first parachute malfunctioned, wrapping its cords around his neck and throwing him into flat-spin at 120 revolutions per minute. Unconscious, Kittinger fell for 73,000 feet before his reserve chute automatically deployed, snapping him awake before landing.

Excelsior II

A month later, Kittinger was back in the stratosphere once again. His team had tweaked the suit and gondola, and he made a successful jump from 74,440 ft. With that altitude under his belt, he set his sights on 100,000 feet. From that staggering height, if anything went wrong, death was almost guaranteed.

Excelsior III

On August 16, 1960, weighted with 320 lbs of gear, Joseph Kittinger stood 103,000 feet above the surface of the earth. Because the right hand glove of his pressurized suit had malfunctioned, his hand had swollen to twice its size. But he had decided to keep this information from the ground crew; they had come too far and the mission’s funding was too vulnerable to abort now.

As he prepared for the “long, lonely leap,” he took in his surroundings:

“The spectacle was breathtaking. I could see a thunderhead boiling up above Flagstaff, Arizona, 350 miles to the west. I could make out Guadalupe Pass in Texas to the east. It was almost like a painting. I can’t really describe the feeling I had hanging there in that tiny gondola and seeing this magnificent planet set against the utter backdrop of outer space. I suddenly had a powerful and unfamiliar sense of my own remoteness from everything I cherished in life.”

Kittinger now stepped to the edge of the gondola. From 19 miles above the earth, he jumped.

In the stratosphere there is no atmosphere, no wind, and thus no sensation of speed. But though he couldn’t feel it, Kittinger was gaining 22 miles an hour per second as he plummeted to earth. He hurtled through space and sky at over 600 miles per hour, approaching the speed of sound (in comparison, the average skydiver jumps from 13,000 feet and will only reach 115 mph). Kittinger was in freefall for over 4 minutes. It took 13 minutes and 45 seconds for him to finally reach the ground. (Think about a location that’s 14 minutes from your house and then think about falling from the sky for the entire time it takes to get there.)

With his amazing dive from the heavens, Kittinger had accomplished an impressive set of records: highest manned balloon flight, highest parachute jump, highest freefall, and longest freefall. Despite our strides in technology, these records have stood for fifty years. Other men have tried to break them and failed. Some have been killed in the attempt.

Encore

For most men, leaping from space would have thoroughly quenched their desire for adventure. Joseph Kittinger is not most men. His work on Project Excelsior was only the beginning of a life that forever sought a challenge.

Kittinger could have stayed on doing research projects in Ohio but instead volunteered for combat service in Vietnam. Having never flown in combat, he felt he “owed it to the United States Air Force” to serve in that capacity.

After two tours of duty in Vietnam, he was stationed in Germany and finally got to enjoy some relaxation. But the not-so-friendly skies kept calling to him, and he volunteered for one more tour in Southeast Asia. This time he was made squadron commander of the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron, the Triple Nickel. As a leader he volunteered for all sorts of missions; he had a firm policy of not ordering men to do jobs he was unwilling to do himself.

And so 17 days before going home, Kittinger volunteered for a mission and was shot down during a dogfight with a MiG. He was taken prisoner, tortured, and spent 11 months at the infamous Hanoi Hilton. He was released after 11 months. Decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Silver Star, the Air Medal and the Purple Heart, Kittinger retired as a colonel from the Air Force in 1978.

But he would not stay grounded.

Kittinger did sky writing for a couple of decades, “barnstormed” around the country taking passengers for rides in biplanes, and won several hot air balloon races. He wasn’t finished setting records either. He made the first solo balloon flight across the Atlantic Ocean, setting a distance record while he was at it. Not the least bit surprisingly, he was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1997.

Now almost 82 years old, Kittinger has not still not retired to a life of golf and prune juice. In fact, in a way his life has come full circle. He is a member of the Red Bull Stratos project which for over three years has been working on a mission to get Felix Baumgartner to break the speed of sound by having him jump from 23 miles up. Kittinger is advising Felix on how to do what no other man has been able to in half a century-break his record for the longest, loneliest leap.

Read Part 2: Nick Piantanida’s “Magnificent Failure”

Source: Come Up and Get Me by Joseph W. Kittinger and Craig Ryan