There are people we really love — friends and family we consistently enjoy and feel strong affection for.

There are people we completely despise — folks we positively can’t stand.

Then there is a category of people which sits right in between. You might call them “frenemies,” though the “enemy” part of that compound can feel like too strong a descriptor. Social scientists have a better term for these kinds of ties: “ambivalent relationships.”

Both positive and negative elements exist in every relationship. In a good, supportive relationship, the positive significantly outweighs the negative. In a bad, aversive relationship, the negative significantly outweighs the positive. In an ambivalent relationship, neither the positive nor the negative predominates; your feelings about the person are decidedly mixed. Sometimes this person is encouraging, and sometimes they’re critical. Sometimes they’re fun, and sometimes they’re a drag. Sometimes they’re there for you, and sometimes they’re not. Sometimes you really like and even love them, and sometimes they bug the ever-living tar out of you.

We can have ambivalent relationships with co-workers, friends, family, and even our spouses. And while we don’t tend to think about our ambivalent relationships as much as we do those on the more polarized ends of the affection spectrum, they actually make up about half of our social networks.

If we feel so lukewarm about ambivalent relationships, why do we end up in so many of them?

Sometimes you see enough good in a new acquaintance to feel intrigued, and to put aside their more annoying qualities to keep giving them chances and getting to know them. In the early stages of any relationship, its newness generates a dopamine-derived haze that magnifies the other person’s better qualities and downplays their flaws. However as time goes on, and this haze wears off, those flaws increasingly come to the fore and feel progressively more bothersome. But, by that time, you may have hung out enough with the person that it feels like you’re friends, and it’s hard to break up with a friend.

Sometimes the connection you feel with someone is very strong when you first meet, but over the subsequent years and decades, you change, and they change, so that your lifestyles, outlooks, and personalities end up more and more disparate. You still think of yourselves as friends, and still have a bond built on a shared history, but your connection is more conflicted than it once was.

Sometimes you’re friends with someone because your spouse is friends with their spouse. They’re not someone you would have actively chosen to be friends with, but because you spend time together as couples, you end up in a relationship, albeit an ambivalent one.

Sometimes you’re just thrown together with people. There are office colleagues and fellow church congregants and roommates who you neither strongly like nor strongly dislike, but that you come to feel quite familiar with because of how much time you spend together. Sometimes this familiarity rises to the level of affection, and sometimes it doesn’t, and sometimes the relationship just kind of is what it is.

Sometimes you simply fail to invest in the maintenance of a marriage. At the start of the relationship, the positive greatly outweighed the negative; over time, and several seasons of neglecting to cultivate your connection, the latter has risen to the level of the former.

And, of course, there’s the whole dynamic of family. You may have grown up around certain blood relations, but you otherwise share little in common, and the fact you still get together is based more on biological bonds, and the expectations around filial piety and familial obligation, than genuine desire and enjoyment. You’re in fact more likely to have ambivalent relationships with family members than friends, which makes sense; while relationships with friends are a matter of voluntary choice, you end up connected to family members by chance.

Why Ambivalent Relationships Are So Terrible for You

Supportive relationships have been shown to buffer stress, boost resilience, and improve physical and mental health.

Aversive relationships have been shown to amplify stress, diminish resilience, and damage physical and mental health.

You might think that because ambivalent relationships feel middle-of-the-road, their impact on your life would be similarly neutral. But in fact, multiple studies have shown that their effect is significantly and uniformly negative, and that “ambivalent relationships not only are less effective at helping individuals cope with stress but also may be sources of stress themselves.”

Studies have found that your blood pressure goes up more when you interact with someone with whom you have an ambivalent relationship, than it does when you interact with someone with whom you have a supportive relationship. Even just anticipating interacting with an ambivalent tie triggers a greater increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Researchers speculate that this heightened stress response is due to the unpredictability of an ambivalent relationship: Are you going to enjoy your time with this person or are you going to get in a fight? Are you going to have fun or just feel annoyed? Are they going to be supportive or critical?

We might hypothesize a couple other reasons that cardiovascular reactivity increases when interacting with ambivalent ties.

One is the greater exercise of self-control you have to muster during one of these interactions; you have to check yourself from rolling your eyes, showing signs of your boredom or frustration, offering an overly harsh rebuttal to an opinion you strongly disagree with — and this takes effort. The heightened stress response experienced around ambivalent ties may also be due to the psychic split you feel over whether you even want to be hanging out with this person at all. You don’t dread seeing them the way you might the dentist, but you don’t really look forward to seeing them, either. The interaction feels more compulsory than voluntary, more obligatory than willful, and we feel a measure of frustration when we don’t experience ourselves as fully autonomous and have to do things that are contrary to our personal desires.

Here’s the really surprising thing: blood pressure not only rises more when you’re interacting with an ambivalent tie versus a supportive one, it also rises more when you’re interacting with an ambivalent tie than it does when you’re interacting with an aversive one. In other words, you feel more stressed when interacting with someone you like/dislike, than you do when interacting with someone you entirely dislike.

The reason for this counterintuitive phenomenon goes back to the uncertainty surrounding an ambivalent relationship. With an aversive relationship, you know exactly where to set your (very low) expectations. You already know the interaction isn’t going to be pleasant. You’re inured to its inherent negativity. You also don’t care about an aversive person, so if they say or do something negative or hurtful, you take it with a grain of salt. With an ambivalent tie, however, you never know what you’re going to get, and this unpredictability creates stress. Plus, since you do care about them, and may have a close relationship with them, when they say or do negative things, it’s significantly more irksome. You can never entirely relax in the presence of an ambivalent friend.

Given that we feel stressed when interacting with ambivalent ties, we unsurprisingly turn to them a little less often than we do to our supportive relationships, whether in a positive (e.g., sharing good news), negative (e.g., sharing bad news), or neutral context. And when we do turn to our ambivalent relationships, we’re less open and share less about ourselves and what’s going on in our lives. This is likely because, as research has found, we don’t experience the responses of our ambivalent friends/partners/family members as supportive. In fact, research suggests that even when an ambivalent friend offers active support when you’re in the midst of tackling something stressful, their presence doesn’t have any stress-buffering effects whatsoever, and isn’t any better than having no support at all.

We might hypothesize that people also tend to share less with their ambivalent ties because self-disclosure is one of the primary things that builds intimacy, and people are, well, ambivalent as to whether or not they want to get closer to folks they have such mixed feelings about. People think, “Well, we’re in a relationship, and sharing things is what people in a relationship do, but I’m not 100% sure I even want to be in this relationship, so I’ll share, but I’ll only share a little.”

This emotional distancing and disengagement only leads to deeper ambivalence. Studies have found that spouses who feel ambivalent about each other have less intimacy in their marriage.

Whether from the stress, the lack of effective support, the impoverished intimacy, or the general burden of constantly keeping a handle on conflicted feelings, people who have a greater number of ambivalent ties in their social network are more likely to experience cardiovascular reactivity, anxiety, interpersonal conflict, and depression, and may even suffer accelerated aging as well. And this is true regardless of the number of supportive ties they also have in their network.

In short, ambivalent relationships are pretty terrible for your all-around well-being.

How to Deal With Ambivalent Relationships

When psychologist Julianne Holt-Lunstad, who authored many of the studies cited above, began to get a sense of the impact that ambivalent relationships have on people, a subsequent question naturally arose: If ambivalent relationships are so potentially detrimental, why do people maintain them?

While she found that people gave various answers, from external barriers like being stuck in the same workplace, to feelings of obligation, folks most frequently said that they held onto their ambivalent ties because of the positive aspects they perceived in these relationships.

You might be maintaining your ambivalent relationships for a similar reason. But once you know what the research says about these ties, you might want to reevaluate this assessment, considering whether a certain relationship really is a net boon in your life, and if it ultimately isn’t, how to mitigate its potentially negative effects.

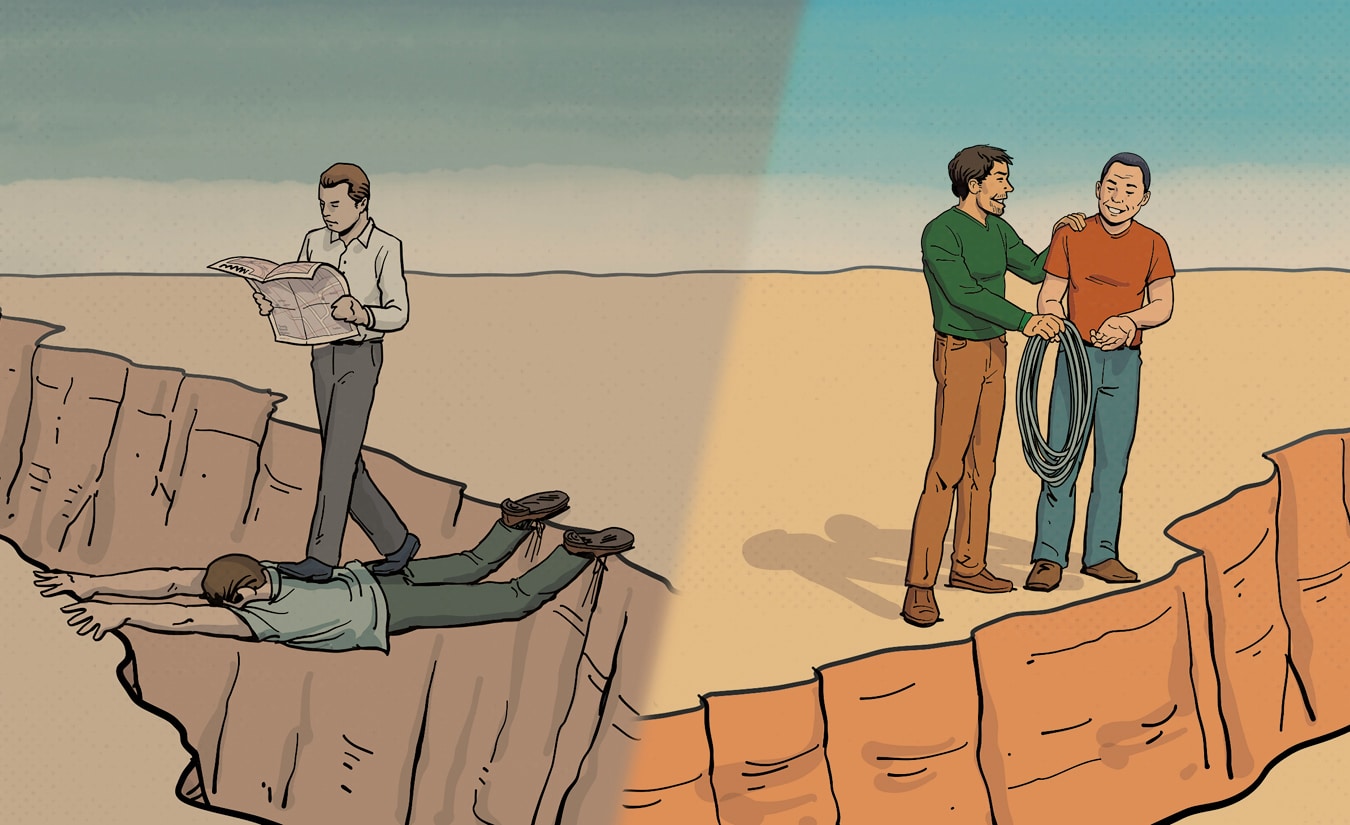

When it comes to how to do that, your recourses to action take three primary forms: removing the relationship, reframing the relationship, or recalibrating the relationship’s ratio of positive to negative elements. Which of these three R’s you should pursue depends on which category a particular relationship falls into.

The first category of ambivalent relationships includes people you feel generally indifferent about. You don’t share some backstory like a long history or a family bond. These people annoy and frustrate you, and while there’s some good to the relationship too, contemplating losing that good only makes you shrug your shoulders. People you were randomly thrown together with — roommates, co-workers, associates in the various organizations to which you belong — are apt to fall into this category.

Removal is your best strategy here, and you should feel free to pursue it without guilt, as it will benefit your life with minimal downside. Request to do more fieldwork outside the office; avail yourself of WFH options; request to serve in a different position at church; find a new roommate (or decide to live by yourself) once your lease is up. Of course, you can’t always easily extricate yourself from these situations, but doing so may be more possible than you think, and if it isn’t possible to get away from an ambivalent person altogether, you can at least look for ways to put more distance between you. As Eric Barker recommended in our podcast interview with him, keep the relationship strictly transactional.

The next category of ambivalent relationships includes people you do have a backstory with — family members or folks you’ve been friends with for years — and do feel possess some positive aspect you’d like to hold onto. However, when you really think about it, you realize that your backstory with this person is the positive aspect of the relationship, and the relationship doesn’t actually impart something good to your life outside of it.

How to navigate these relationships represents one of the thorniest, most difficult questions in life. On the one hand, you have a righteous desire to be committed and loyal. This person may have done a lot for you and you want to reciprocate. You may feel like you owe them. On the other hand, you want to look out for yourself, and while you may sometimes protest to the contrary, you have probably viscerally felt that these relationships are a net drag on your life.

There are no easy answers here. If there’s one bit of advice that’s universally applicable, it’s that everyone can probably put a little more distance between themselves and this kind of relationship than they currently have. You can have a little less contact. You can say no a little more often. If you struggle to do so without guilt, keep these things in mind:

1) While the desire to be loyal is a worthy one, it’s not always connected to a higher plane of virtue, but to an ingrained evolutionary impulse — a basic instinct to contribute to mutual survival that isn’t nearly as relevant and applicable in the modern age. 2) Just because you share a past with someone doesn’t necessarily mean you need to share a future. 3) While you feel like you may “owe” people, the extent of this debt, and when it is “paid,” is inherently subjective and unclear. For example, people often say that children “owe” their parents for raising them. Yet, speaking for ourselves, neither of us experiences parenting as an altruistic, unselfish endeavor. Instead, we feel that our kids have at least given us as much as we’ve given them; our lives would be hugely impoverished without them! We don’t feel like either party owes the other; it’s a reciprocal, mutually beneficial relationship. 4) The language of obligation is often thrown around in the absence of investment, i.e., someone doesn’t make the effort to be the kind of person you’d willfully want to have a relationship with, and so they resort to appealing to duty to keep you tied to them. Might we all be better off if we based relationships more on genuine, mutual, voluntary, intentional, earned connection and affection, rather than a standard like “years known” or where it is that people randomly, passively fall in a family tree?

A third category of ambivalent relationships includes people with whom we do feel a genuine connection and who do offer a real, perhaps even irreplaceable, aspect of positivity, even if they sometimes drive us bananas. These folks may be worth holding onto, but not in the context of the default relationship you currently maintain.

Here you can work to mitigate some of the frustration and stress this type of relationship can generate in your life, by reframing your expectations for it.

Oftentimes, we want every friend to be the end-all-be-all for us — someone with whom we connect on nearly every level. These kinds of bosom buddies are surely one of life’s greatest treasures, but they are a rarity, rather than the norm. With most people, there are going to be places you align, and places you conflict. The trick to appreciating these folks is not to expect them to be a relational jack-of-all-trades, but to enjoy them for their particular “specialty.” You wouldn’t call a carpenter to unclog your sink, and you shouldn’t call your fun-but-not-particularly-empathetic friend to talk through some setback. Enjoy people in the contexts in which they shine, while avoiding interacting with them in the contexts where they frustrate. Don’t expect your flaky friend to show up for you at the hospital, but appreciate what a hoot he is at parties. Don’t expect your overly-competitive brother to ever be able to play basketball with you without losing his cool, but appreciate the way he always has good feedback about how to build your business.

Marriage represents the final, special category of ambivalent ties. Having pledged a solemn, voluntary vow to your spouse, you should want to stick around and feel a duty towards making your marriage last. And you probably want to experience a level of intimacy with them that goes beyond only connecting in certain contexts.

Nearly every romantic relationship starts with a very high degree of positivity, and a very low degree of negativity. But in the post-honeymoon period, the latter can begin to creep up, both because spouses start to take each other for granted — slacking in the little niceties and affection-building behaviors that once drew them together — and because the goggles of new love fall off, so that each partner begins to see flaws in the other they hadn’t noticed before. After the swooning season subsidies, romantic partners may not come to outright despise each other, but the feeling between them may turn decidedly “meh.”

Fortunately, the closeness of marriage, the fact that you have so many moments of daily interaction, provides plenty of material that can be rejiggered towards a better and more intimate relationship. If the happiness of early love rested on having a positive ratio of good to bad in the relationship, the task of the ambivalent couple is to restore that balance. You can find a complete guide on how to make these kinds of positive deposits in your relational “bank account” here.

Life’s Too Short to Live in a Relational Gray Area

It would be short-sighted and immature to expect everyone in your life to be someone with whom you’re well matched. In reality, you won’t come to really like the vast majority of people you meet. Yet within this sizable cohort of ambivalent ties will reside plenty of folks who may serve valuable roles in your life. Learning to get along with various kinds of people and navigate interpersonal differences is part of how we grow as humans.

Yet, there’s a difference between life-enhancing stress, which works towards your greater good, and life-negating stress, which simply grates. Discerning which category your ambivalent relationships fall into takes an ample dose of phronesis — the kind of intentional reflection which most people don’t engage in when it comes to this area of their lives.

Research shows that people have as much contact with their ambivalent ties as they do their primarily positive ones, and while they turn to the latter a little more often than the former for support, they still lean on their ambivalent relationships quite a lot too, despite the fact that the support those relationships offers doesn’t actually feel supportive. This suggests that many people hold onto ambivalent relationships from a fear of loneliness, and the feeling that having someone, anyone, around is better than having no one.

It’s true that loneliness carries its own significant risks to physical and mental health, and no research has yet directly studied which is worse for you: having lots of ambivalent relationships or being alone. But in most cases, folks don’t have to make such a binary choice. Ambivalent ties only make up half of the average person’s social network, so that if they choose to distance themselves from their lukewarm relationships, half of their ties will still remain. Shrinking your social circle in this way so that it’s dialed down to just the people who are true positives — opting for quality over quantity — may ultimately be more of a gain, than a loss; life’s too dang short to spend it hanging out in the tepid gray zone of relationships.

___________

Citations for all the research studies mentioned above can be found in this summary paper authored by Julianne Holt-Lunstad and Bert N. Uchino.