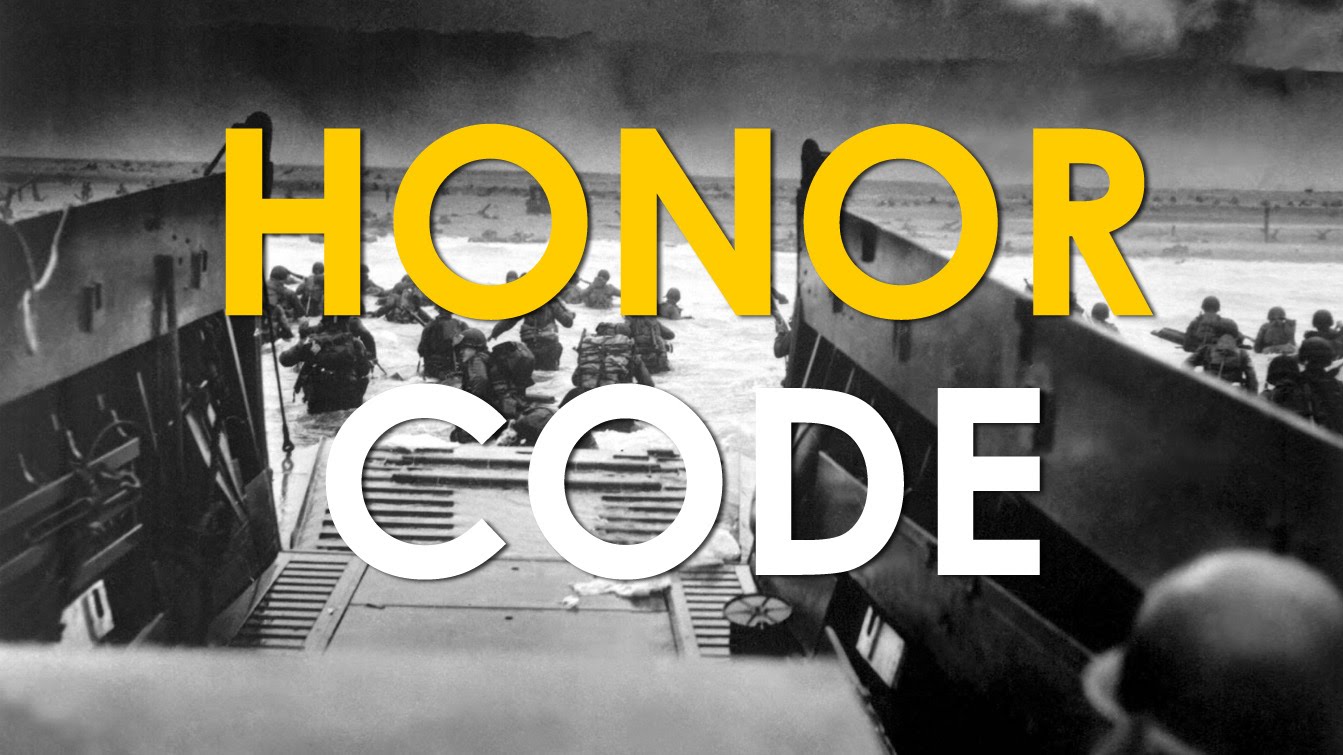

When we think about affairs of honor in 19th-century America, our minds typically bring up images of well-dressed gentlemen facing each other at dawn, pistols gleaming in the morning light. The duel — with its elaborate codes, precise choreography, and aristocratic flourishes — has captured our collective imagination as the quintessential way men settled disputes of honor in the past.

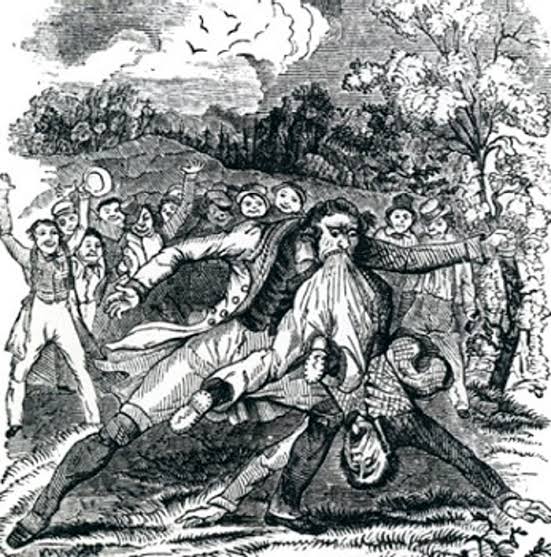

But there was another tradition of honor running parallel to the gentleman’s duel — one that was far more brutal, common, and chaotic: the rough and tumble.

You’ll often hear biologists talk about how mammals — including humans — engage in “rough and tumble play.” Rough and tumble play is cute. It’s roughhousing.

But the rough and tumble in 19th-century America was the opposite of cute.

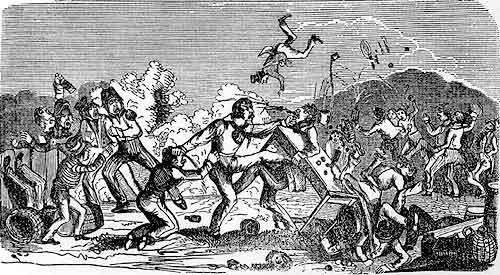

It was a no-holds-barred style of fighting where pretty much anything went. The goal was to disfigure your opponent permanently. We’re talking about gouging out eyes, biting off ears and noses, and fish hooking someone until their cheek tore.

I first came across the practice of rough and tumble fighting way back when we wrote our series about male honor. Ever since I learned about it, I’ve been fascinated by it. The idea that men would regularly try to gouge each other’s eyes out over perceived slights seems almost incomprehensibly savage from our modern perspective. Yet for thousands of working-class American men in the 19th century, this brutal form of combat was as normal and socially acceptable as settling disputes through lawyers is today.

Below, we take a look at this forgotten, but important, practice of American honor culture.

The Scotch-Irish and the Birth of American Brutality

The rough and tumble traces its roots back to the fighting traditions of the Scotch-Irish immigrants who flooded into America during the 18th century. They were a pastoral people who came from the borderlands between England and Scotland — a region where life was hard, government was weak, and personal honor was often the only thing standing between a man and his livelihood.

In a pastoral culture, such as was practiced by many Scotch-Irish, your livestock was your livelihood. The problem with animals is that bandits or a rival family could easily steal them. As a consequence, shepherds not only kept a constant eye on their flocks and herds, but they also developed and maintained a reputation for violence to deter would-be thieves. If someone messed with you or your family, an 18th-century Scotch-Irish man was expected to respond with brutal force. Killing someone over a slight wasn’t off the table.

When these immigrants settled in the backcountry regions of the American South, they carried this violent notion of honor with them. How that violent honor manifested itself began to splinter across class lines. Southern aristocrats, wanting to distinguish themselves from black slaves and lower-class whites, looked to European aristocrats as a model of settling disputes of honor. From European nobles, the Southern gentleman borrowed the code duello — an elaborate code of conduct governing duels that emphasized decorum and restraint. The goal of the code duello seemed to have been to curtail brutality, while still allowing for a man’s sense of offended honor to be restored.

Meanwhile, the poorer class of Scotch-Irish continued to use the raw violence of their ancestors to settle scores. Scratching, biting, hair pulling, and eye gouging were all fair game. The goal of this style of fighting wasn’t just to defeat your opponent; it was to mark him permanently, to leave visible, lasting proof of his humiliation. This style of honor fighting among the working-class in the South became known as the rough and tumble.

Rules? What Rules?

Unlike dueling, which required knowledge of complex codes of conduct, expensive weapons, and social connections to arrange the affair properly, anyone could engage in a rough and tumble. It was democratic. All you needed was a grievance and a willingness to endure unspeakable pain.

That’s not to say there were no conventions at all. Rough and tumble fights typically began with a ritualized challenge. One man would announce his readiness to fight by issuing a specific throwdown to his opponent. A man of honor had no choice but to accept. The challenger could ask, “Rules?” His opponent could then respond with something like, “Queensbury rules.” But he was apt to just say: “rough and tumble.” And when he did, the violent melee would begin right there and then.

There’s an episode of Disney’s old Davy Crockett show that shows this back and forth before a rough and tumble (hat tip to Dying Breed reader Mark McGrath for sharing this with me):

Before the actual fighting started, the combatants would usually strip to the waist. This served a practical purpose as clothes could be grabbed. But it also served as a symbolic gesture indicating that this was a serious business; there was real skin in the game.

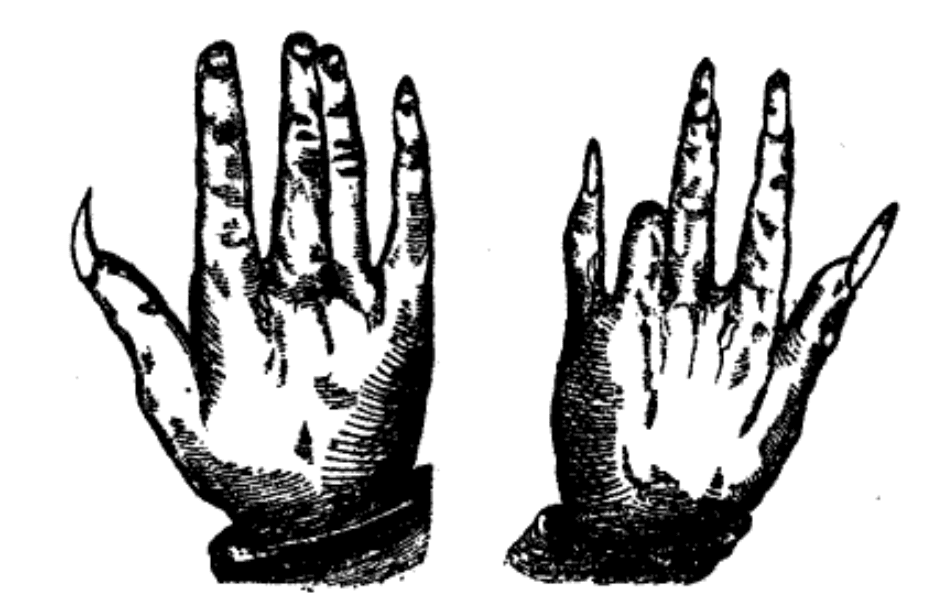

Once the fight began, conventional rules of fair play went out the window. Gouging out eyes was not only acceptable but expected. In fact, eye gouging was so common in rough and tumbles that this style of fighting was often called “gouging.” Some men even grew their fingernails out to increase their gouging efficiency.

Grabbing a man by the hair and bashing his head into the ground or a nearby tree was par for the course. Biting off ears and noses was considered good technique. Fish hooking was a go-to tactic in rough and tumbles. A fighter would jam his finger (or fingers) into his opponent’s mouth and hook it into the corner of the cheek, then pull violently in an attempt to tear the flesh. The goal was to rip the corner of the mouth open. Some fighters would even attempt to twist and tear their opponent’s testicles.

A rough and tumble ended when one man either couldn’t continue or acknowledged defeat.

The Rough and Tumble Spreads

In the 19th century, the rough and tumble gained wider notoriety through “Crockett almanacs.” These cheaply produced pamphlets portrayed Davy Crockett and other Southern-born frontiersmen taking part in rough and tumbles and boasting of their gouging skills. The tales cemented the image of the American frontiersman as a man who solved problems with raw violence. It also helped spread the rough and tumble across the country.

It even cropped up among Northern men. Historian Lorianne Foote notes that working-class Union soldiers often settled disputes with rough and tumbles, while middle and upper-class officers stuck with aristocratic dueling conventions. Once again, class shaped the form honor disputes took.

If you’ve seen Martin Scorsese’s epic film Gangs of New York, you’ve actually seen a Yankee version of the rough and tumble. It’s the scene where Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, Amsterdam Vallon, squares off with Bill the Butcher’s heavy, McGloin (played by Gary Lewis). The fight begins like a boxing match but quickly devolves into a rough and tumble, ending with a near fish hook before Bill the Butcher calls it off. Besides capturing the spontaneous brutality of the rough and tumble, the film also gets the cultural context right. Such fights weren’t fought between gentlemen. Both Vallon and McGloin were Irish immigrants, and they duked it out in the working-class slums of the Five Boroughs.

The Death of a Violent Tradition (Mostly)

So what led to the decline of the rough and tumble? Two main factors converged to hasten its demise. First, the rise of professional law enforcement, which shifted dispute-settling to the state, and second, evolving ideas of masculinity, which increasingly frowned on extreme violence as a way to adjudicate honor.

Yet the tradition never vanished completely. Variations still surface in isolated communities today. During a podcast I did with Stayton Bonner about bare-knuckle boxer Bobby Gunn, we discussed the Irish Traveller community Bonner grew up in. In that culture, men still settle disputes of honor by stripping to the waist and fighting with bare hands until an opponent is maimed and gives up. Like their historical predecessors, when a Traveller engages in a rough and tumble, there’s eye gouging, fish hooking, and testicle twisting. It’s a brutal echo of honor’s violent past.

For more on how the idea of male honor has changed over the centuries, check out our series on the subject.