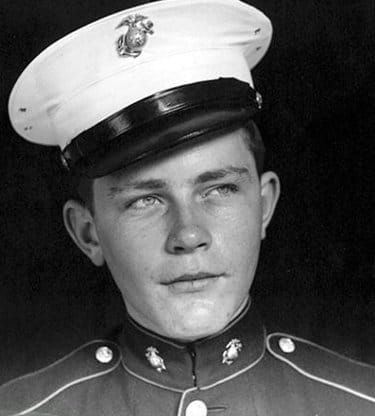

On September 9, 1965, Navy pilot James Stockdale was flying a mission over North Vietnam when his A-4 Skyhawk took anti-aircraft fire. The cockpit filled with smoke. Warning lights flashed red. He ejected, breaking a leg in the process.

As his parachute carried him toward a crowd of villagers armed with machetes and pitchforks and the certainty of captivity loomed, Stockdale had one clear thought: “I’m leaving the world of technology and entering the world of Epictetus.”

You see, Stockdale wasn’t your typical hotshot naval aviator. He was also a philosopher — albeit an accidental one. In 1959, six years before his plane was shot down in Vietnam, the Navy sent him to Stanford to get his master’s degree. There, he met the philosopher Phil Rhinelander, a World War II veteran who introduced him to the Stoic philosopher Epictetus.

Years later, when his plane was shot down and he was imprisoned in the infamous POW camp known as the “Hanoi Hilton,” Epictetus’s Enchiridion would become a survival manual for Stockdale and the men he led. It would also help birth a guiding principle that got Stockdale through seven and a half years — four of them in solitary confinement — of torture and debasement: what’s now called the “Stockdale Paradox.”

The Stoic in the Hanoi Hilton

As the highest-ranking U.S. officer in the Hanoi Hilton, Stockdale became his fellow prisoners’ de facto leader. He organized secret communication systems by tapping on the walls, created a code of conduct for resisting interrogation, and encouraged a culture of courage, or what he called “hard-heartedness.”

Through all the trials and tribulations, Stockdale said, “I lived on the wisdom of Epictetus.”

Stockdale would recite lines from the Enchiridion silently to himself in the dark. He reminded himself that his captors could control his body, but not his will. They could take away everything external, but not his “inner citadel,” as the Stoics called it.

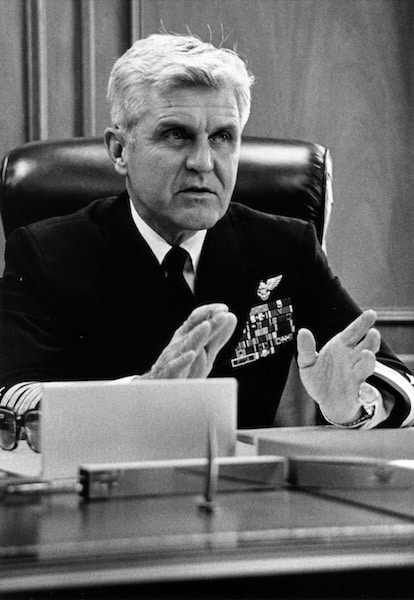

After seven and a half years in captivity and enduring excruciating torture, Stockdale’s war finally ended. On February 12, 1973, he was released as part of Operation Homecoming — the U.S. mission that brought American POWs out of North Vietnam. He was among the first group to leave the Hanoi Hilton.

The men were loaded onto transport planes and flown to Clark Air Base in the Philippines. As the aircraft crossed the Vietnamese coastline, Stockdale later wrote that he felt “a sense of completion — of having seen the worst that man can do, and having come through it with my honor intact.”

When the plane landed, officers and reporters saw a gaunt figure stepping carefully down the ramp, gray-haired, limping, and visibly fragile. He was 49 years old. He saluted sharply and, according to Navy accounts, his first words were characteristically dry: “I’m fine. I’ve been in worse places.”

After a quick medical evaluation, doctors cataloged the damage: a broken back, a fused knee, and other injuries that would keep him from flying again. He began the slow process of physical recovery and reintegration into everyday life. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1976 and devoted the next 30 years to leadership, teaching, and public service.

From 1977 to 1979, he served as president of the Naval War College, where he developed a curriculum focused on ethics and character under pressure. He told young officers that the development of virtue was the foundation of strategy.

After retiring from the Navy as a vice admiral in 1979, Stockdale returned to Stanford as a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution. There, he lectured and wrote about philosophy, duty, and the discipline of command. He published a few books based on his experience as a prisoner of war and how philosophy helped him get through it, including Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus’s Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior.

In 1992, Ross Perot (the guy with big ears and charts) tapped Stockdale as his running mate on the Reform Party ticket. Millions of Americans first met him on live television when he opened the vice-presidential debate by asking a pair of unusual and characteristically philosophical questions, “Who am I? Why am I here?”

It was an opener that summed up a man who’d spent his life asking those questions when the answers held the highest stakes.

After the campaign ended, Stockdale returned to teaching and writing. He never chased celebrity. He knew his mission in life: keep translating Stoic philosophy into a language sailors, soldiers, and ordinary citizens could understand.

The Birth of the Stockdale Paradox

Decades after Stockdale was released from prison, business writer Jim Collins interviewed him for his book Good to Great. Collins asked how he managed to survive when so many didn’t.

Stockdale paused and said:

You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

That single sentence became known as the Stockdale Paradox.

In practice, it meant living in two opposing realities at once: facing the brutal truth of the moment while maintaining unbreakable faith in the eventual positive outcome.

Stockdale told Collins that the men who didn’t live to see the light of freedom were often overly optimistic. “They were the ones who said, ‘We’ll be out by Christmas.’ Then Christmas would come and go. Then Easter. Then Thanksgiving. And they died of a broken heart.”

Hope unmoored from realism collapses under its own weight.

Stockdale’s insight wasn’t unique to him. In another prison camp two decades earlier, psychiatrist Viktor Frankl made the same observation.

In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl described how prisoners who tied their survival to a specific date — “we’ll be home by Christmas” — often perished when that day came and went. Their hope snapped under the pressure of unmet expectations.

According to Frankl, the individuals who managed to survive often adopted a “tragic optimism.” It meant finding meaning in your suffering so that you could endure it.

Both men discovered that real hope isn’t naïve. You have to face reality squarely. It is only by accepting how terrible things are that the faith to endure can grow.

Practicing the Paradox in Everyday Life

Most of us will never be POWs, but we’ll all face our own dark nights of the soul: financial setbacks, illness, loss, betrayal, uncertainty. The Stockdale Paradox can help guide you through these moments.

Here’s how to put it into practice:

- Face the facts. Don’t sugarcoat what’s in front of you. But don’t dramatize it, either. Just call a spade a spade. Your business is tanking. Your marriage is on the rocks. Your kid is struggling. You can’t fix what you won’t look at.

- Keep faith in the long game. Stockdale never doubted he’d go home. He just stopped pretending it would happen in the immediate future. Real hope doesn’t live on a timetable. Keep faith that things will be alright in the end, accepting that the positive outcome you desire may happen later rather than sooner.

- Focus on your circle of control. Epictetus’s favorite idea: distinguish between the things you can influence and the things you can’t. Effort, honesty, and attitude are in your control. Outcomes aren’t.

- Find meaning in the suffering. Frankl said that those who had a why could bear almost any how. Stockdale’s why was leading and taking care of his men and upholding his honor as a soldier. Yours might be keeping your family’s spirits up during a dark time. Find your why.

Desperate Times Call for Rational Insanity

Stockdale once joked that surviving required a form of “rational insanity” — the ability to see how bad things were and still say, “We’ll make it.”

That’s the paradox distilled. You acknowledge the ugliness of your current suffering while still believing that things will work out. You balance the realism of a soldier with the faith of a saint.

You can see the same mindset in everyday life: the single dad putting himself through night school while working and taking care of kids; the woman going through harsh chemotherapy that’s killing the cancer in her body, but also her body at the same time; the business owner scrambling to meet payroll in a struggling business. None of them pretends it’s easy. They just refuse to call it hopeless.

Practicing the Stockdale Paradox means learning to live in the tension between truth and hope, control and surrender.

So face the facts. Keep the faith. But don’t expect to be home by Christmas.