I finally got around to watching Casablanca this year. I’m a little embarrassed it took this long. I think the delay was due to the fact that I already thought I’d seen it, on account of seeing clips of it so often. It’s part of the ether of pop culture. I knew all the famous lines from the film because they’ve become part of our lexicon: “Here’s looking at you, kid.” “We’ll always have Paris.” “I think this is the start of a beautiful friendship.”

When I actually did watch the whole thing for the first time, a lot of the beats were indeed familiar. But some things certainly felt fresh, one of them being the themes that jumped out to me. I knew the film centered on a romance, but it turns out to not only be about love itself, but something more profound: the way love can lift a man out of his cynicism and into higher virtues.

Rick Blaine: The Cynical Hustler

The movie takes place in 1941. The world is starting to come apart. Refugees from all over Europe have flooded into Casablanca, a city in French Morocco under the jurisdiction of the Vichy government — the Nazi-collaborating regime in unoccupied France. They’re all hoping to get an exit visa to Lisbon.

The town becomes a waiting room for people trying to escape the chaos of war. You can feel the existential angst there. People can’t go home, and they don’t know how long they’ll be stuck in limbo. The uncertainty breeds anxiety.

While Casablanca is a temporary stop for everyone, for Rick Blaine, it’s home.

Rick (played by Humphrey Bogart) is an American running a popular nightclub and casino called Rick’s Café Américain. It’s the place everyone goes: Vichy officials, Nazi officers, refugees, resistance fighters, and thieves. Everyone goes there because Rick has created a space where anything can happen. He’s taken a hard stance of neutrality on everything going on. As long as you’re a paying customer and behave yourself, you’re welcome to hang out at his cafe.

But to maintain that neutrality, Rick has to keep everything and everyone at arm’s length. He never drinks with customers. He never shows emotion. And, as he says himself, he definitely never, ever sticks his neck out for anyone.

Rick Blaine embodies what some modern film analysts call the ‘Cynical Hustler’ archetype. A deliberate withdrawal from moral participation characterizes it. The Cynical Hustler convinces himself, and those around him, that he is motivated solely by profit and self-preservation.

Rick presents himself as a businessman and nothing more. He keeps conversations short and transactional. When people come to him with problems, he listens just long enough to make it clear he won’t be helping.

Caring, in his mind, is for suckers.

But the interesting thing about Rick is that he wasn’t always like this.

In fact, in a previous life, he was a serial idealist.

In 1935, he ran guns to Ethiopia (a losing cause). In 1936, he fought for the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War (another losing cause).

So how did guns-a-blazing idealist Rick Blaine end up as Cynical Hustler Rick Blaine?

The same way all idealists end up jaded and cynical: he got wounded.

What Cynicism Really Is

Cynics often like to talk about their detachment and aloofness as if it were a wise stance to take towards the world.

But psychology doesn’t consider cynicism to be wisdom or intelligence. In clinical psychology, cynicism is sometimes described as a stance that offers a “protective shell of skepticism” that shields an individual from overwhelming emotion, specifically guilt, shame, and heartbreak. Cynicism is the psyche’s way of ensuring it’s never blindsided by disappointment again. Comedian George Carlin summed it up well when he said, “Inside every cynical person, there is a disappointed idealist.”

Rick’s cynicism stems from being a very disappointed idealist.

Before he ended up in Casablanca, Rick lived in Paris. This was 1940, shortly before the Nazis invaded. Amidst the tension of an imminent Nazi takeover, Rick began a love affair with a beautiful, charming woman named Ilsa (played by Ingrid Bergman). Rick had planned for them to leave Paris together via train as the Germans advanced. But on the day they were supposed to depart, Ilsa never showed. Rick waited for her on the platform in the rain until his friend brought him a letter from Ilsa saying she could never see him again, but offering no explanation for this gut-wrenching ghosting.

It devastated Rick and turned him into the Cynical Hustler. Having been heart-stompingly blindsided, he wanted to make sure it never happened again.

Many men can relate to Rick.

A guy goes through a bad breakup or a divorce and comes out the other side with a new philosophy: don’t expect much, don’t invest too deeply, and definitely don’t trust anyone too much. He calls it being realistic.

A guy gives ten years to a company, and then is unceremoniously laid off after a restructuring meeting. From then on, every promise has an asterisk and anyone who still talks about “mission” sounds naïve to him.

A guy watches a church or civic organization implode and decides that getting involved in groups is stupid. He still shows up out of obligation. But he does the bare minimum while offering running commentary about all the obvious problems going on and how it’s all bound to fall apart.

When men turn cynical, it’s usually because they were disappointed by someone or something. And because acting wounded feels weak, a lot of guys take the cynical stance. It makes you feel wise and above it all.

But as Tom Wolfe put it in The Bonfire of the Vanities, “cynicism [is] a cowardly form of superiority.”

Cynicism lets you feel smart and tough — without ever having to put any skin in the game. You get to be the guy ready with the wry comment about how something will never work. You don’t have to commit, or risk being wrong, or look foolish for caring. When you take the cynical stance, you just sit there, arms crossed, slightly amused, waiting for everything to confirm what you already “know.”

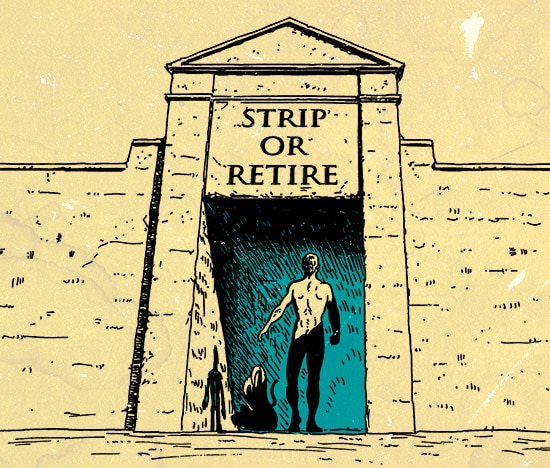

Sure, cynicism might spare you another disappointment, but it does so by keeping you on the sidelines, watching other people take the risks that actually make life meaningful. You’re spared the lowest lows, but, you don’t get to experience the highest highs, either.

You Must Remember This: Love Is the Cure for Cynicism

As Casablanca progresses, you slowly see Rick begin to shed his shell of cynicism.

And love is the catalyst for his transformation.

Ilsa shows up at his cafe with her husband, the dashing resistance fighter Victor Laszlo. She and Laszlo are trying to get out of Casablanca before he’s recaptured by the Nazis.

At first, Ilsa’s appearance tears the scab off Rick’s wound, and he becomes even more cynical and jaded. But when Ilsa explains why she stood Rick up back in Paris, Rick softens. He forgives her. And his love for her starts flowing again.

He hatches a plan to get both Ilsa and Laszlo to safety. And in the process, he overcomes his cynicism.

Rick has two letters of transit that allow passage out of Casablanca. Cynical Hustler Rick could have used them to get him and Ilsa out of Dodge and continue their love affair.

But that’s not what he does.

Instead, Rick does the noble thing. The good thing. He sends Ilsa off with Laszlo. He knows she would regret abandoning her husband, he knows Laszlo is fighting for a noble cause, and he knows Laszlo needs Ilsa to continue his work.

Rick gives up the thing he wants most because it’s the right thing to do.

Rick’s love for Ilsa starts as romantic longing, but it doesn’t stay there. It widens into a willingness to sacrifice for her husband, for the fight against the Nazis — for people he’ll never meet. Plato argued that love ascends up a ladder: romantic love can inspire a desire for higher and higher forms of the Good. That’s what love does at its best; it pulls a man out of private desire and toward something larger than himself.

What Men Can Take From Rick Blaine on Overcoming Cynicism

Rick’s path out of cynicism is one many men could learn from.

Here are a few takeaways:

1. Cynicism usually has a backstory. Most men don’t become cynical because “the world is stupid.” They become cynical because they were blindsided by something. It’s worth asking yourself: When did I start becoming cynical? What triggered it?

Naming the source of your cynicism is the first step in overcoming it.

2. The cure for cynicism is love. Rick doesn’t break out of his shell by talking to himself about it. He does it by opening his heart to love. Once he lets his heart expand in his love for Ilsa, he gains the capacity to love freedom, justice, and honor.

3. Emotional investment is risky, but rewarding. Detachment avoids disappointment. It also avoids meaning. Rick is more alive in the final ten minutes of the movie than he is in the first hour, and it’s because he finally allows himself to feel and express love. Caring about people means you’ll be disappointed sometimes. That’s the cost of love. But there’s a greater cost to never caring about anything at all.

Conclusion

Rick Blaine starts Casablanca as a man who believes detachment is the same thing as strength. He’s cool, controlled, careful . . . and living in the shallow comfort of the cowardly.

By the end, he’s risked his life, lost the woman he loves, and chosen giving a damn over safety.

He learns that while cynicism keeps you protected, it also keeps you on the sidelines. Rick decides he doesn’t want to be irrelevant anymore. He wants his choices to matter for the big, important, and noble things in life. He overcomes his cynicism by taking a chance on love.

If you continue to live within a cynical shell, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.