In the last several years, talk about the idea of “self-care” — doing things to care for your own mental, emotional, and physical health — has become more and more common. At first, the term felt a little cringey and self-indulgent, something used largely amongst women-focused lifestyle blogs to rationalize booking a spa day and by the wellness industry to sell pampering products.

But if self-care has sometimes been overused as a buzzword, its fundamental premise is still quite sound. In any time, the frustrating, stressful, anxiety-ridden, existential-angst-generating nature of modernity can wear a person down, and the past year has only highlighted this fact all the more acutely. Consequently, folks have come around to the idea that to stand a chance of keeping your head above water, practicing self-care is vital — for both women and men alike.

If, despite the penetration of self-care into the cultural zeitgeist, you still struggle with feeling like it’s sissified, indulgent, or simply not something for which you have time, it’s helpful to realize that men with arguably the most pressure-filled job on earth — serving as leader of the free world — made time for self-care. While they wouldn’t have called it that, many American presidents pursued habits, pastimes, and hobbies that were intentionally designed to ameliorate their stress and rejuvenate their mental and physical faculties. They didn’t do so despite the taxing nature of their work, so much as because of it; rather than being selfish, these practices allowed presidents to “sharpen the saw,” restoring their ability to function in their demanding duties.

Below we highlight five examples of the way past POTUS-es did self-care, as inspiration for prioritizing your own.

Abraham Lincoln — Theater

He had never seen Shakespeare performed on the stage until he became President. After that he rarely missed an opportunity. In February and March 1864, at one of the most dangerous periods of the war, he took time off from his duties to see the great tragedian Edwin Booth perform in Richard III, Julius Caesar, The Merchant of Venice, and Hamlet. —David Herbert Donald, Lincoln

Though Abraham Lincoln became a fan of literary drama, especially Shakespeare, amidst the dogged self-education he undertook as a youth, opportunities to see these works performed on the stage were virtually non-existent for him before arriving in Washington to serve as president. From then on, however, theatergoing became a regular source of escape and entertainment — even when, in fact especially when, the turmoil of the Civil War deepened. It’s estimated that Lincoln attended over 100 plays during his time as president, or, on average, about once every other week.

Lincoln always went to the theater with a friend or adviser, eschewing his security detail’s near-constant warnings against being in crowds of any sort. These outings weren’t slyly about politics or strategy; they were about socializing and Lincoln getting the chance to remove his thoughts from the war. As an article from the Ford’s Theatre Foundation notes: “Theatres were places people could forget their everyday lives and concerns.”

Think about how immersive the experience of going to a theater is — the darkness, combined with the stage lighting, focus your attention almost like blinders on a horse. At the end of a long show, you come out of the theater almost in daze, wondering what time it is and how the hours passed so quickly — and, hopefully, enjoyably. One can picture the lanky president coming out of the theater with a smile on his face, having relieved his stresses, even if just for a few hours. It is, of course, the saddest of ironies that his life was taken from him in a theater — a place he so loved — right when he was first able to appreciate the closing of the war years.

Rutherford B. Hayes — Genealogy

I have an attack of genealogical mania. It came on about ten days ago, superinduced by reading a family tree which a friend sent me. It is in a violent form but I trust it will soon abate. —Rutherford B. Hayes, in a letter to a relative

You’ll be forgiven for doing a double take at the name of our 19th president. In most polls, he’s actually among the least recognized of our country’s 44 chief executives. He served a single term — by his own choosing — in the midst of Reconstruction, from 1877 to 1881. His election was one of the most contested and corrupt in history; until 2000, Hayes was the only candidate to lose the popular vote but win the electoral college. The nation was still trying to heal itself from the Civil War, and the Gilded Age of full-throttled industrialism was just beginning to gain steam (literally, in the form of the steam engine). Hayes had plenty to concern himself with, and yet found time to pursue his lifelong passion: genealogy.

Today, it’s easy to think of genealogy as a mostly sedentary pursuit; just head to ancestry.com and let the internet do most of the work for you. In the 19th century, it wasn’t nearly so passive. From a young age, when he first met his extended relatives, Hayes developed his passion for exploring his own ancestry, which later in life expanded to include an interest in his wife Lucy’s family tree as well. This involved writing a flood of letters addressed to unknown people in far-flung places, as well as a lot of traveling to visit libraries and genealogical societies. Hayes’ research wasn’t just about gathering names and filling in lines on his family tree, either; he wanted to actually meet and converse with the relatives he came to identify. It was a pastime that filled his soul to the brim, especially when he could get away to take part in reunions and various heritage festivals.

While his pre-political life and retirement were the most fruitful periods for his hobby, he did find entire days at a time during his governorship of Ohio and as president to roam the countrysides and find more genealogical branches. Though he wasn’t a great president, perhaps Hayes’ knowledge of his family’s past contributed to both his optimistic nature and largely corruption-free tenure in the White House. As Brett and Kate wrote regarding the practice of genealogy, “It makes you think more about the choices you’re making now and how they might affect your posterity.”

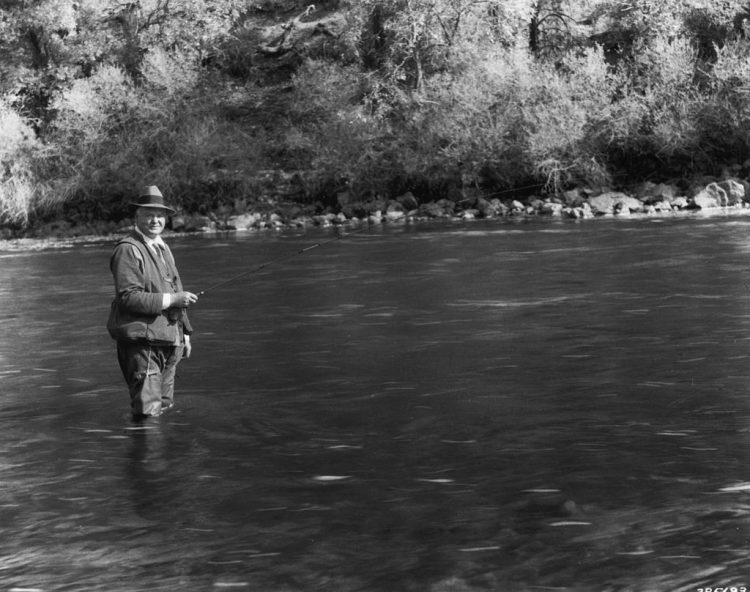

Herbert Hoover — Fishing

Herbert Hoover was never more at peace than he was standing in an Oregon stream in search of rainbow trout or trolling off the coast of Florida for fighting fish. Public service was his vocation, but fishing was his respite from a hectic world. —Senator Mark Hatfield

Of all the presidents, perhaps none were as committed to and enamored with their pastimes as Herbert Hoover was with fishing. The love affair started early in Hoover’s life, when he roamed the Iowan prairies and streams he grew up on, sometimes hauling in over 100 fish in a single outing. Those experiences cemented a passion that was truly lifelong, lasting up until his death in his late eighties. No mere hobbyist, Hoover became an expert fisherman who, as one biographer observed, “mastered nearly every kind of freshwater and saltwater fishing,” and even wrote a book on the subject, Fishing For Fun — And to Wash Your Soul.

While his time as president is often ridiculed, before that Hoover was a superb businessman and one of the true administrative heroes of World War I. His level-headedness and optimism — which served him well before his presidency, but rather poorly during the Great Depression — can be attributed to his time spent in the great outdoors. He said it himself, “This civilization is not going to depend upon what we do when we work so much as what we do in our [own] time.” How we spend the latter feeds and informs the quality of the former. As regards fishing, Hoover truly believed that the qualities cultivated by the master angler mirrored those that were needed in broader society: patience, optimism, realism, humility, and respect.

Franklin D. Roosevelt — Nightly Cocktail Hour

Serving for over 13 years and in the midst of two of America’s most monumental crises — the Great Depression and World War II — meant that Franklin Roosevelt needed a lot of recuperation time, especially given his already poor health. He took frequent one- and two-week fishing vacations, read mystery novels at night, and most memorably, hosted a nightly cocktail hour in which all talk of war and politics was barred. Franklin often whipped up the drinks himself (even during Prohibition), making them strong and experimenting with different liquors and mixers rather than sticking to a single favorite.

These gatherings allowed FDR to, as one researcher put it, “cast aside the burdens of his office and socialize with friends and associates.” Eleanor, owing to both a childhood steeped in alcoholism and her more dour personality, wasn’t a fan of her husband’s cocktail hours, as she felt the time could be better used to discuss important policies and plans for the nation. But Franklin found them beneficial enough to his mental health to continue hosting them up until his death in office.

As could only be expected, the rule that banned any political or strategic conversation was not strictly followed every day. You get enough political people in a room together, and the subject will naturally come up. Nonetheless, the very idea of it kept the heavy topics from dominating; more idle subjects of interest included the latest books/movies, DC social gossip, and whether the local Senators baseball team had a chance at the pennant (the answer, in those years, being a confident “no”).

Doris Kearns Goodwin was such a fan of FDR’s practice, which she discovered while writing a biography of him, that she adopted it herself; one of the ways the historian and author escapes the anxieties of work is by planning social events with friends and family on an almost nightly basis, with the same rules applied: for a few hours each evening, talk of work or politics is banished.

Dwight D. Eisenhower — Golf

Without golf, he’d be like a caged lion, with all those tensions building up inside him. If this fellow couldn’t play golf, I’d have a nut case on my hands. —Major General Howard Snyder, Eisenhower’s personal physician

While William Howard Taft wasn’t the first president to golf, he was the first to be open about it, bringing the game to the masses where it had previously been known only as a sport for aristocrats. Since then, only two presidents — Truman and Carter — have stayed off the links.

As common as the prevalence of golfing amongst presidents, is the criticism they receive for it. Disparagement of a president for golfing too much, to a degree that, observers argue, must surely detract from his official duties, has become more common in the last 12 years, but Ike certainly wasn’t immune to it during his tenure as POTUS more than a half century ago. On an annual basis, he did in fact golf more than President Trump (and far more than President Obama, for those keeping score). He hit the course twice every week, and most afternoons found him literally puttering around the White House lawn.

Democrats used this image of a golf-happy Eisenhower to condemn him as a “do-nothing president.” Yet Harry Truman, who himself had criticized what he perceived to be Ike’s lackadaisical approach to leadership, defended his successor on this score: “To criticize the President . . . because he plays a game of golf is unfair and picayunish. He has the same right to relax from the heavy burdens of office as any other man.”

Indeed, golf provided an essential release valve for one of Ike’s weaknesses: a famously fierce temper. His stress and anger would often build up so strongly that his psychic turmoil would manifest itself in a number of physical maladies, from frequent gastrointestinal problems to multiple heart attacks later on in his public career. The guy clearly needed to take a load off, and golf helped him do that; as Jean Edward Smith notes, the game was “as necessary to [Eisenhower’s] mental health as a good night’s sleep.”

And it wasn’t a solo hobby for him; joining Ike on the links for over 20 years was his “Gang.” They were an intimate group of friends who knew of his health and temper problems and sought to make those few hours out of doors as enjoyable and leisurely as possible. Though political talk wasn’t entirely escapable, it cannot be denied that the game of golf improved his mood, his decision making, and his physical health, which ultimately allowed him to cement a place among the top 10 American presidents.

Some Concluding Thoughts

In my research of these men I found that their self-care practices shared some notable characteristics that can offer a few lessons applicable to us all:

1) Do things that offer a change of pace from your typical work. For these presidents, their self-care practices offered a pivot from the work they had to do as POTUS to a different stripe of activity. From orchestrating the real-life drama of war, to spectating the fictional drama of theater. From sitting in an office, to sitting along a river bank. From talking politics to talking baseball.

Leisure time isn’t as rejuvenating when it’s too similar to work time: going from staring at a screen to edit spreadsheets, to staring at a screen to scroll through social media, doesn’t provide a sufficiently refreshing change of pace.

Note too that these presidents’ pastimes weren’t entirely passive pursuits; they necessitated effort (even Lincoln’s theater habit required going out instead of staying in), skill, and/or attention. The goal of a self-care practice is not necessarily physical or mental loafing, but to ease the burden of whatever is causing you anxiety — to get your mind off of one thing and onto another. As an old saying goes, “A change is as good as a rest.”

2) Make socialization part of your self-care. Most of these pastimes were done socially, and in a number of cases, that was part of the entire point. For Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Eisenhower, the pastime itself was nice, but not complete without the social and conversational aspect. Social connections help lighten our burdens. So while hobbies, and self-care in general, are often thought of as solo pursuits, and certainly sometimes should be, don’t discount the power of doing them with others too.

3) Pursue multiple outlets for self-care. While people often have one activity they’re most passionate about, living a well-rounded and psychologically resilient life requires developing a rich and varied “portfolio” of interests. Though I featured just a single pastime for each of the above men, there were others that could have been mentioned: Eisenhower enjoyed painting and playing bridge; Lincoln read voraciously and loved telling stories/jokes (especially bawdy ones!); and as mentioned above, Roosevelt enjoyed frequent fishing vacations. The presidents also invested in their relationships with family and friends. Their lives were constructed on multiple pillars of support.

4) Create your own personal self-care routine. Each of these men’s pastimes were different, as each of their personalities was different. Don’t copy the specific activities of these routines (unless you’re also interested in those things), rather, adopt the general insight that every man needs time — often quite a bit of time, or at least more than you’d perhaps expect — to rejuvenate his spirit. Find a few things you personally like and pursue them, knowing and appreciating that they’re for your unique mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual health alone.

My own self-care includes walking and hiking, baking, and reading (a lot!) and writing my newsletter (though I also read and write a lot for my job, reading and writing for pleasure instead of work offers a satisfying change of pace). Each of those pastimes include individual and social elements: I often walk around the neighborhood alone, but hike the local mountain trails with my wife, kids, and other friends and family; the time I spend with books is nearly always done alone, but I share what I’ve been reading in my weekly newsletter and discuss it in a book club with local friends; and even though baking is most often just me in the kitchen with a beer and a podcast, the goods that come out of the oven are always distributed far and wide.

Even though pursuing my hobbies and interests can sometimes feel selfish and frivolous in the moment, and like there isn’t enough time to do something just for me, those are invariably the most refreshing and rejuvenating moments of my days and weeks. When I ignore them on a regular basis, I get tense, anxious, and cranky, and my family notices it. Those “selfish” self-care routines are as crucial to your well-being, and your family’s, as everything else you do.

_________________

Sources

Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald

Rutherford B. Hayes by Hans Trefousse

Hoover the Fishing President by Hal Elliott Wert

Franklin D. Roosevelt by Robert Dallek

No Ordinary Time by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Eisenhower in War and Peace by Jean Edward Smith