Once again we return to our So You Want My Job series, in which we interview men who are employed in desirable jobs and ask them about the reality of their work and for advice on how men can live their dream.

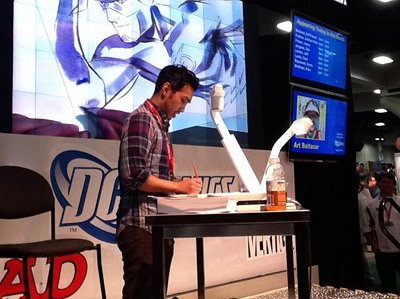

Today we have the pleasure of hearing from Ted Slampyak. Mr. Slampyak is an illustrator who draws the daily comic strip Annie and also works on movie storyboards, most recently for the film Terminator Salvation. Any man who’s doodled has wondered what it would be like to get paid for his drawings. But before you send for the free art talent test advertised on the back of a matchbook, check out Ted’s interview for the lowdown on this profession.

To see samples of Ted’s work, check out his website, Storyteller’s Workshop.

1. Tell us a little about yourself (Where are you from? How old are you? Where did you go to school? Describe your jobs and how long you’ve been at them, etc.)

I grew up outside of Philadelphia. I graduated from Tyler School of Art, a part of Temple University back in 1983, and I’ve been a freelance illustrator ever since. I moved here to New Mexico about twelve years ago.

I’ve been drawing comics — comic books and comic strips — professionally since graduating college, and on an amateur level all my life. My first published work was in some science fiction fan club newsletters while in college. I’m currently drawing the Little Orphan Annie strip, now just called Annie, which still runs in papers around the country and online.

I’ve also been drawing storyboards since college, as a way to apply my comics skills in something that pays well! Last year I worked on storyboards for the new Terminator film — more on that later!

2. Why did you want to become an artist? When did you know it was what you wanted to do?

I’ve been telling stories through pictures for as long as I can remember, since before I could read or write. It’s always just been the way I can visualize and communicate.

3. Did anyone try to steer you away from being artist-telling you couldn’t make money at it?

That’s a great question! You know, thinking back on it… no. I can’t think of anyone who discouraged me. Now, it’s possible that some did, and I was just oblivious to it. My parents were very encouraging but insisted I go to college, so I had a degree to help me whether I pursued illustration or something else. And I’m glad I went to an art college — it gave me some great exposure to so much more than I’d been aware of as an artist.

4. If a man wishes to become a comic strip or storyboard artist, how should he best prepare?

Even more important than making good likenesses, you need to be able to convey different moods, different camera angles, and emphasize different things. That means you need to know how to prioritize what people see and how they “read” the images. There’s a science and an art to composition, lighting and detail that all effect how the reader takes in what you’re showing.

And for comics, for Pete’s sake learn to do professional lettering. It’s as important as the drawing, and so many artists ignore it at their peril.

5. Would you recommend going to art school?

I would recommend getting exposed to as many styles, as many ways of seeing and drawing and painting as you can. Art school is a great way to do that, if you approach it properly, but it’s not the only way. I immersed myself in the parts of the craft I wasn’t so good at — composition and graphic design, typography, light and shadow — and then incorporated those new skills back into my comics work.

And of course, art school can be a great way to meet other artists and build friendships among people who understand what a vanishing point is.

I’ve taught at a couple of art schools, and I’ve seen a lot of young people there who wouldn’t try anything outside their comfort level, or accept that what they’re doing might not be the best way to do things. Why waste everyone’s time? What are you there for? Don’t bother going to art school unless you want to be a student.

6. How did you break into the comic strip business? Do you have any tips for men who wish to do likewise?

I started by creating, writing and drawing my own comic book, Jazz Age. Back in the 90’s, there were no web comics, so I had to find a small publisher willing to run my book. Nowadays, lots of storytellers make their names and build followings on the web. Though I haven’t worked on it lately, “Jazz Age” is still available.

Jazz Age never had a large readership, but it seemed to get into all the right people’s hands. I’d run into other artists and writers whose work I admired, and they all had heard of the book. Or at least they were being polite!

But even though Jazz Age never paid very much, and usually not at all, I think just about every paying gig I’ve ever gotten in comics, including Annie, I got through Jazz Age. It’s been a terrific portfolio for me over the years, so in that sense it was very much worth the investment in time and labor.

7. How did you break into the storyboard business? Do you have tips for men who wish to do likewise?

I started doing storyboards for ad agencies to sell their ideas to clients over twenty years ago. When more and more movies and TV shows were being made here in New Mexico, I moved into that.

There’s no big secret to breaking into the business. Just put together good samples and get them out there. Get film screenplays and draw up sequences from them — preferably for movies you’ve never seen. Volunteer your work to student films so you can show actual work.

Also, there are web site directories where professionals list themselves. Get on to those and put your samples up. If they’re good, they’ll get you some inquiries.

8. Of your two jobs, comic strip artist and storyboard artist, which do you prefer and why?

I love them both, but wouldn’t like either one as much if it were all I do. Comics gives me a great deal of control over the storytelling, even when I’m not the writer, because I do everything else. Storyboards makes me part of a large team and gives me opportunities to collaborate with lots of talented people — and they get me out of the home office. Being able to switch between the two, as well as doing other freelance illustration work gives me lots of variety and keeps me fresh.

9. Can a man make a living just doing one or the other, or are they the kinds of jobs that alone need supplemental income?

Comics usually don’t pay well, at all. If you’re lucky, you can get involved with a project that’s a good money-maker, but that’s at the upper levels. I’m lucky that Annie gives me a fair income, and it’s steady, week-after-week work, which is rare in the freelance illustration biz.

Storyboards often come with a good day rate, particularly if you’re in a union, but unless you live in a big movie town — say, New York or LA — it can be hard to find enough work. More and more places are, like New Mexico, luring film productions to their area, so more places are finding such opportunities.

10. What is the work/family/life balance like?

My wife is also a freelance illustrator and designer, so we both work at home. That helps when you have to work late hours — you still can see each other, even if you can’t do much together.

But there’s always a need to keep that balance in mind. I try to keep my weekends free as much as possible, and try to finish the day’s work by 5:00 if I can. Keeping that distinction between “work time” and “home time” — even when both are at home — are essential for being able to close the laptop and put it behind you for awhile.

11. What is the best part of your jobs?

With the comic strip, the best part is seeing your work in print — in a comic book, or a newspaper. Or, when it’s published online, getting positive comments and seeing your viewing numbers go up. It’s the closest to applause that drawing can get.

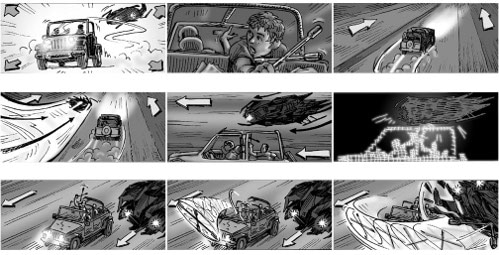

With the storyboards, it’s the praise and feedback that comes from the director or DP (Director of Photography) you’re working with. I spent nearly six months last year working on Terminator Salvation. It was a dream job. I worked directly with the director, McG, in a creative atmosphere where I was encouraged to contribute ideas — some of which made the final cut of the movie. Seeing those few moments was as much a thrill as seeing my name in the credits at the end!

Terminator Salvation Storyboard

12. What is the worst part of your jobs?

Both jobs require creativity whether you’re feeling creative or not. I can’t fake it — I have to come up with new ideas and generate my own enthusiasm. It can be exhausting. Plus, with the comics job, I work at home and don’t have anyone looking over my shoulder, so I need the discipline to keep at it and get it done on time, even when it’s almost painful to stay at that art table.

13. What is the biggest misconception people have about your jobs?

With storyboards, the biggest misconception is no conception at all — many people have no idea what storyboard artists do, or what a storyboard is. When I tell them a storyboard is essentially a script in pictures, they get it.

The biggest misconception I get about comics is when I tell them what I do, and they say, “Oh, do they still publish that?”

14. Any other advice, tips, or anecdotes you’d like to share?

Always be on your best behavior. Dress well, and reassure everyone around you that you’re easy to work with, that you pay attention, you take criticism well and are willing to see the project through the client’s eyes. Remember that people aren’t just buying artwork, but hiring an artist. You. You are the product, as much as your work.

Also: always promote yourself. Don’t expect — as I naively did when I started — that hard work alone will get people talking about you. You have to get the word out. Like this: http://www.storytellersworkshop.com

Tags: So You Want My Job