Welcome back to our series on the libraries of famous men.

Jack London led one of the most interesting and extraordinary lives in history, even though his life was half as long as most. By age 17, he had navigated San Francisco Bay as “Prince of the Oyster Pirates” and sailed the Pacific as a seal hunter. By age 21, he had crisscrossed the North American continent by foot, rail, and steamship and prospected for gold in the Klondike. By age 24, he had become a well-established writer and been declared the “American Kipling.” He wrote the international classic The Call of the Wild at 27, took on the role of war correspondent at 28, became the highest paid writer in America at 30, and set off to sail the world at 31. By the time of his death at age 40, he had established a ranch and authored 200 short stories, 400 non-fiction pieces, and 20 novels.

Described by The San Francisco Examiner as having “instincts of a caveman and aspirations of a poet,” and by his wife Charmian as being both “Doer and Thinker,” London’s incendiary trajectory in life had as much to do with his wild, driven thumos as his sensitive, curious intellect. Indeed, the adventures sought by the former quality, were inspired, facilitated, and accompanied by the latter — especially as it concerns his love of books.

Books as Enticements to Adventure

I’m omnivorous. I read everything I can lay my hands on. —Jack London

It was books that first introduced a young Jack London to new horizons — both in terms of exotic physical locales he might explore and professional heights he might reach — that were wider than the borders of his financially and emotionally unstable upbringing.

London’s sights were first expanded at age eight when he stumbled upon a tattered copy of Signa by Ouida (the pseudonym of English novelist Maria Louise Rame). Though the last section of the book had gone missing, he read and re-read what remained, which told the tale of an Italian youth who battles from an auspicious start to become a celebrated composer and violinist. The story, London remembered, “put in me the ambition to get beyond the sky lines of my narrow California valley and opened up to me the possibilities of the world of art. In fact it became my star to which I hitched my child’s wagon.”

London’s discovery of the Oakland Public Library proved just as revelatory. While his formal education would be truncated and intermittent, within the walls of this edifice he developed a commitment to autodidactic learning that would last a lifetime. The library was fatefully staffed by Ina Coolbrith (something of a literary celebrity in her own right), who mentored the nine-year-old patron and stoked his bibliophilia. After London became a success later in life, he wrote her to say:

Do you know, you were the first one who ever complimented me on my choice of reading matter. I was an eager, thirsty, hungry little kid — and one day, at the library, I drew out a volume of Pizarro of Peru . . . You got the book & stamped it for me. And as you handed it to me you praised me for reading books of that nature. Proud! If you only knew how proud your words made me.

Often lonely as a boy, the Oakland Public Library became a kind of refuge and second home to London. He spent as much time there as he could, checking out as many books as he could; when he reached the limit that he was able to procure under his own name, he had all the members of his family apply for library cards, and then used them to check out more books for himself. He remembered of this time:

I read everything, but principally history and adventure, and all the old travels and voyages. I read mornings, afternoons, and nights. I read in bed, I read at the table, I read as I walked to and from school, and I read at recess while the other boys were playing.

When being the bookish loner brought London to the attention of a school bully who teased the boy for being “a dam sissy,” Jack, though smaller than his antagonizer, knocked him over with a powerful punch to the nose. The roughs at school didn’t mess with him anymore after that.

This was a pattern which would continue throughout London’s young life: He was tough and scrappy enough to drink and brawl with the ruffians who populated the Oakland waterfront, where he would spend an increasing proportion of his youth. But he never gave up his love of reading, never stopped visiting the library when he wasn’t hanging out in saloons, and never stopped thinking that the wider world of ambition and adventure he discovered in books might be something he could seize for himself.

Books as Companions to Adventure

[Jack was] seldom in waking hours without books or spoken argument exerting upon his wheeling brain. —Charmian London

A significant obstacle to London’s nascent reading habit arose at the age of ten, when he was forced to take on multiple jobs to help support his family. Yet he still stuck with his goal of reading “two good-sized books a week,” even when that meant staying up until 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning — leaving him just a couple hours to sleep before he rose to begin delivering newspapers before school.

But when London had to quit school altogether at age 14 in order to work 16-20 hours a day, seven days a week, at a cannery, something had to give. The fact that there were “No moments here to be stolen for my beloved books,” was part of what convinced Jack to seek freer ways to earn an income.

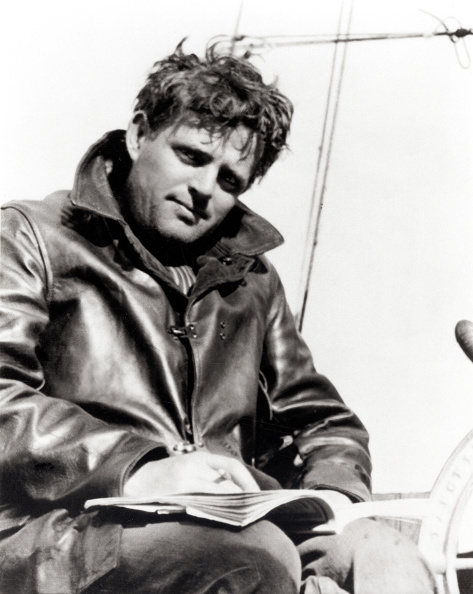

15-year-old London became an oyster pirate, piloting a small sloop in dead-of-night raids. After a night of stealthily plundering areas of San Francisco Bay which had once been public and since been turned into private tidal farms, followed by plenty of cavorting with his gang along the waterfront, London would retire to the cabin of his boat, to crack open his beloved books. This would be the beginning of a new role for books — as constant companions in adventure — which would last throughout London’s entire life.

When London journeyed to the Bering Sea to hunt seals as a 17-year-old seaman, he brought along a sack of books which included Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, and most appropriately, Moby-Dick. While wintering in an abandoned mining camp in the Yukon, London whiled away the freezing, blizzard-filled weeks by reading. His partner on the prospecting trip remembers the 21-year-old as a “strong, vital man, full of the joy of living and getting the most from life [who] soon had found every book in camp and eagerly devoured every bit of reading matter he could secure.”

Later in life, when a thirtysomething London attempted to sail around the world with Charmian, he stocked the ship with a 500-volume library, which included books by Joseph Conrad, Henry James, Rudyard Kipling, and Robert Louis Stevenson. London deliberately made literary pilgrimages part of the voyage’s itinerary as well, stopping in the Marquesas to see the setting of Melville’s Typee, and on the island of Upolu in Samoa to visit the gravesite of Stevenson. Even though reaching the latter required an arduous hike up a jungle-covered mountain, London made the trek happily, quietly saying to Charmian as they turned to leave the memorial, “I wouldn’t have gone out of my way to visit the grave of any other man in the world.”

Books as Facilitators of Adventure

There is so much good stuff to read and so little time to do it in. It sometimes makes me sad to think of the many hours I have wasted over mediocre works, simply for want of better. –Jack London

Doing stints in various, and variously exploitative, labor jobs in between his adventures, as well as seeing the lives of men who had been broken by the economic system as he tramped around the country, convinced a young Jack London that his ticket out of an oppressive, impoverished life didn’t lie in his body, but in his mind. Books were his way out, and his way up.

After he returned from the Klondike, London determined that he needed to hit those books in a more systematic way than he previously had. When a return to high school at age 19 didn’t work out, he decided to cram for the University of California’s rigorous entrance exams — passage of which was the only requirement for admission.

London committed himself to learn years of material in just three months, eagerly buckling in for the superhuman challenge ahead. Holed up in a small room at the back of his parents’ house, he sat at a small table with a stack of books and studied for nineteen hours straight, seven days a week. Though Jack retired to bed at midnight and rose at five, he jumped out of bed each morning with relish and enthusiasm; as he wrote of his fictional alter ego, Martin Eden, “Never had the spirit of adventure lured him more strongly than on this amazing exploration of the realm of the mind.”

English, science, math, history — Jack uploaded it all into his brain. As he worked through chemical formulas and quadratic equations with only scant rest, “his vitality,” Charmian wrote, “was taxed almost to bursting. His muscles twitched . . . Even those dependable sailor-eyes wavered and quivered and saw jumbled spots, but as always through life, he won out.”

London passed the three-day entrance exams with distinction and was granted entry to Berkeley. Yet he only spent a semester there, finding that college did not live up to his expectations, and feeling he could learn more through self-study than by sitting in a classroom.

Thereafter, London committed himself to trying to make it as a writer. In between doing odd jobs, he relentlessly penned essays and articles in every possible genre, and sent them to every possible magazine. Yet all he received in return was a stack of rejection notices.

He knew he needed to improve the quality of his writing, and turned to reading as the vehicle to do it. He not only read books specifically about writing, like Herbert Spencer’s Philosophy of Style, but he pored over the work of literary greats past and present, reaching back to Homer, Shakespeare and Milton, as well as examining contemporary favorites like Poe, Melville, and Kipling. He would not only read these and other books, but copy down the texts (especially Kipling), to better move their literary rhythms into the marrow of his mind. In “unlearning and learning anew,” he searched for the “principle[s] that lay behind and beneath” the writings of eminent authors so that he might recombine them into a style that was wholly original and entirely his own.

In his pursuit of becoming a professional writer, Jack kept to the same Herculean schedule he had adopted while studying for the university entrance exam: 19 hours of work; five hours of sleep. Wash and repeat, seven days a week. He would write during the day, only taking breaks for eating and reading (and he would do the latter while engaged in the former, holding a fork in one hand and a book in the other). At night he’d visit the Oakland Public Library, and return to read the armfuls of books he checked out. If he wasn’t writing, he was reading, and so it went until his work finally broke through to public acclaim.

Books facilitated the adventure of achievement, and the spoils of achievement would facilitate further adventures — via travel, farming, ranching, and more.

The Library of Jack London

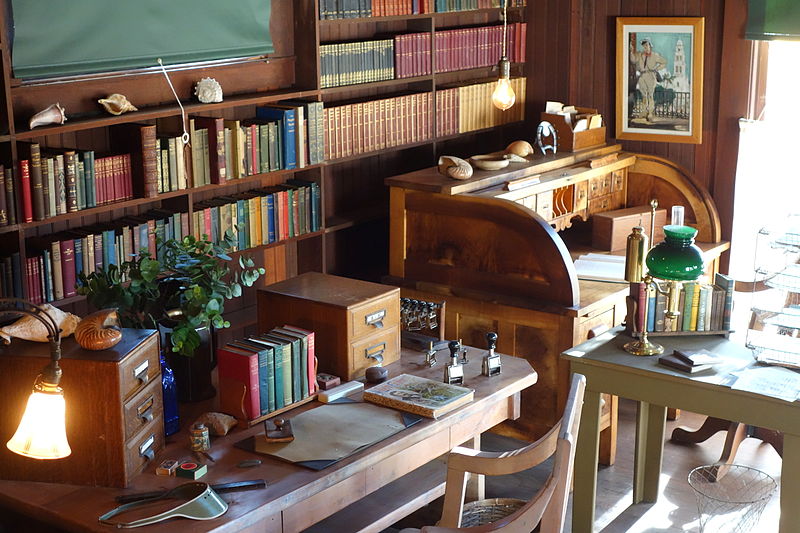

While Wolf House was being built in Glen Ellen, CA, Jack moved into a cottage on the property and set up shop in this study, which, Charmian remembered, involved “an orgy of book-arranging.”

I regard books in my library in much the same way that a sea captain regards the charts in his chart-room. It is manifestly impossible for a sea captain to carry in his head the memory of all the reefs, rocks, shoals, harbors, points, lighthouses, beacons, and buoys of all the coasts of all the world; and no sea captain ever endeavors to store his head with such a mass of knowledge. What he does is to know his way about in the chartroom, and when he picks up a new coast, he takes out the proper chart and has immediate access to all information about that new coast. So it should be with books. Just as the captain must have a well-equipped chart room, so the student and thinker must have a well-equipped library, and must know his way around that library.

I, for one, never can have too many books; nor can my books cover too many subjects. I may never read them all, but they are always there, and I never know what strange coast I am going to pick up at any time in sailing the world of knowledge. –Jack London

Given the prominent role that books played in Jack London’s life, it’s no surprise that part of what he most looked forward to in building Wolf House — his dream home — was being able to retreat to its large study, underneath which, connected by a spiral staircase, would sit a large library where he could store his collection of 15,000 books (which was so large, it had until then been stockpiled in various locations).

London would never realize his dream; Wolf House tragically burnt to the ground days before he and Charmian were set to move in. But we fortunately still have a good idea of many of the volumes that would have lined the shelves of its library.

To view the seminal bookends of London’s reading life, we would see on one side the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Herbert Spencer, and Charles Darwin, which developed in his youth a worldview of stark realism and rational materialism — of life as a strictly biological matter of survival of the fittest. On the other side, sits a book which electrified Jack in a way he hadn’t experienced since discovering those authors 20 years prior. Carl Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious made London feel that “I am standing on the edge of a world so new, so terrible, so wonderful, that I am almost afraid to look over into it.” As his biographer Earle Labor observes, “[Jack’s] reaction was a shock of recognition, for his ‘primordial vision’ — Jung’s term for this creative gift — had distinguished much of London’s best fiction from the start.” London’s discovery of Jung would energize his emerging interest in myth, folklore, and spirit and catalyze a renewed period of creativity that would tragically be cut short by his untimely death.

In between these bookends, Jack read many, many more books. Here is a small selection of them (with a few annotations taken from Tools of My Trade):

- Signa by Ouida

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens

- Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens

- Rudyard Kipling’s complete works — whom he read “quite steadily”

- On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

- Herbert Spencer’s works

- A Genealogy of Morals by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Das Kapital by Karl Marx

- Paradise Lost by John Milton — companion on his first voyage to the Yukon

- Through the Gold Fields of Alaska by Harry de Windt — “as well as other books about the region . . . the Klondike was London’s great and most important adventure and literary resource”

- Shakespeare’s complete works

- Voices of the Night by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- The Ring and the Book by Robert Browning

- Alfred Lord Tennyson’s works

- Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s complete works

- Tales of Soldiers and Civilians by Ambrose Bierce

- The Cynic’s Word Book by Ambrose Bierce (later retitled The Devil’s Dictionary)

- Black Riders by Stephen Crane

- The Social Contract by Jean Jacques Rousseau

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Primer of Philosophy by Paul Carus

- Foster’s Complete Hoyle (card game encyclopedia)

- Leo Tolstoy’s complete works

- Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

- Joseph Conrad’s complete works (only near the end of his life did London feel worthy of writing letters to Conrad as a peer)

- The Oregon Trail by Francis Parkman

- Anecdotes of Dogs by Edward Jesse — “provided him with information about canine behavior”

- My Dogs in the Northland by Egerton Young — “gave him accurate data about the traits of sled dogs”

- Elinor Glyn’s novels — which London liked so much he wrote the author asking for autographed copies

- The Social Unrest by John Brooks

- Henrik Ibsen’s plays

- Our Benevolent Feudalism by William James Ghent

- Life of Jesus by Ernest Renan

- Rooseveltian Fact and Fable by Annie Hale

- Oscar Wilde’s non-fiction works

- Sailing Alone Around the World by Joshua Slocum — read with Charmian, who wrote: “It was the book that got us started planning our own trip”

- The Jungle by Upton Sinclair — read multiple times, including once by Charmian who read it aloud to Jack

- The Fat of the Land by John Streeter — for building his ranch; “especially for information about the best kind of chickens to buy, the perfect hog pen, and other helpful farming hints”

- Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Dana — for which he wrote an introduction

- The Will to Believe by William James

- Thomas Carlyle’s works

- Foxe’s Book of Martyrs

- Geronimo’s Story of His Life by Geronimo

- Studies in Deductive Logic by William Jevons

- Fishing for Pleasure and Catching It by Edward Marston

- Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

- Typee by Herman Melville

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

- Edgar Allan Poe’s complete works

- Matthew Arnold’s works

- John Ruskin’s works

- The Practice of Medicine by William Francis Waugh

- Psychology of the Unconscious by Carl Jung — London wrote that “It is big stuff”; his copy contains over 300 notations, more than any other in his library

To learn more about the life of Jack London, listen to my podcast with his biographer, Earle Labor:

Tags: Books