“Boxing is the sport to which all other sports aspire.” -George Foreman

All sports have the potential of becoming about much more than athletics, transforming into symbols of a culture’s and country’s mood, insecurities, conflicts, and hopes. But perhaps no sport lends itself to this kind of transposition more than boxing. For the purity of boxing gives it the nature of a blank canvas; there is no playing field or special equipment; the rules are few and easy to understand. There is but two men, facing off with nowhere to go, with only their fists and their determination to decide their fate. Thus boxing easily becomes a metaphor for debates over our values: good vs. evil, immigrant vs. nativist, bravado vs. humility, intellect vs brute strength.

The idea boxing has most often been over-layed with is manliness. Joyce Carol Oates (boxing may be a manly sport, but some of the best books on it have been written by women), argues that boxing’s appeal lies in the fact that it is “without a doubt . . . our most dramatically ‘masculine’ sport.'” Indeed, the sweet science of bruising has for its entirety history been inextricably tied up with a culture’s perception and conception of manhood.

This connection to cultural ideals and masculinity has given boxing a volatile history. At times when society felt its manliness to be on the wane, boxing was wildly popular and seen as the iron needed to fortify a pansified culture. At other times, people have recoiled as boxing’s perceived brutality, seeing the sport as evidence of a barbarism at odds with a perception of themselves as too enlightened for such pursuits. All of which makes for a fascinating history and a subject every man should know something about.

Boxing in Ancient Times

The Terme Boxer, Greek sculpture from the first century B.C

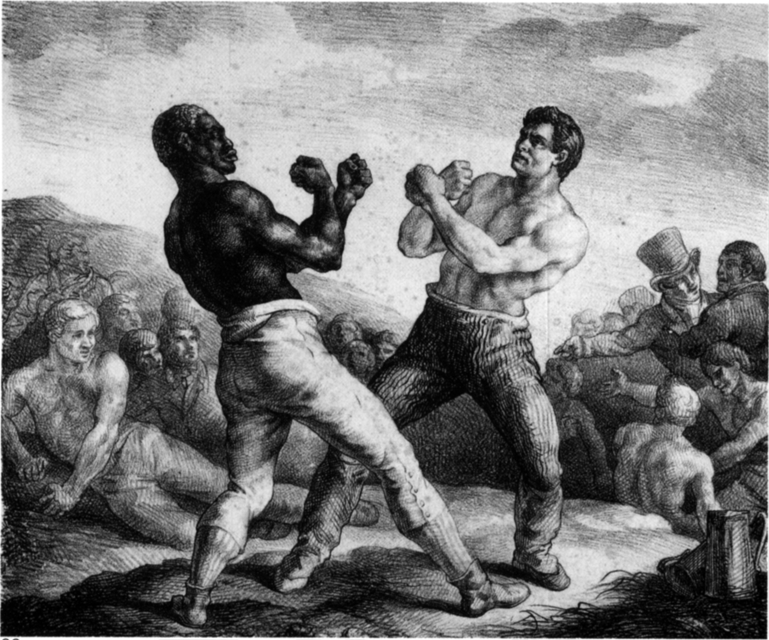

Boxing has likely been around since the dawn of time. Our caveman ancestors surely put up their dukes when fighting another dude for a hunk of meat or the heart of a cavelady. The first hard evidence of boxing can be found in third millennium Egypt and Mesopotamia. The first record of a “prizefight” occurs during the funeral games for Patroklus as recorded in the Iliad. Boxing moved from ceremony to sport with its inclusion in the Olympics and the other Panhellenic festivals. Still, this was boxing in its most primitive form: no rounds, ring, weight classes, rest periods, or points systems. A boxer was declared the winner when his opponent could no longer continue and cried uncle. Boxing was also quite popular in Ancient Rome both as a sport and as part of the Gladiator contests. Gladiators would wrap their hands and forearms with leather straps, sometimes studded with metal shards (the cestus), and battle it out, often until death.

Boxing in the Age of Enlightenment

When the traditions of Ancient Greece and Rome fell into obscurity during the Middle Ages, boxing was eclipsed by popular Medieval pursuits. Commoners still got into the occasional scuffle, but the aristocratic class concentrated on activities like jousting, archery, and hunting. It was not until the upper-classes began taking an interest in boxing in the early 18th century that boxing would really begin to flourish.

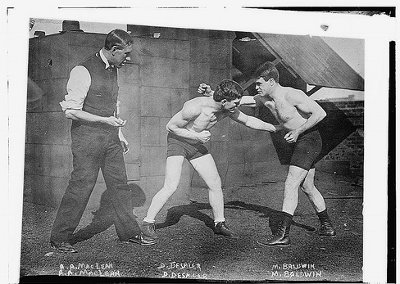

During the Age of Enlightenment, Europeans took a keen interest in recovering the knowledge and traditions of antiquity. Such curiosity brought with it a revived interest in boxing, especially in England, the true birthplace of modern prize fighting. Wealthy patrons supported their chosen pugilists and put huge wagers down on their fights. With such great sums on the line, the need for rules to settle disputes soon became clear. In 1743, rules governing the sport were set down. The rules regulated the behavior of umpires and seconds and made it illegal to hit a fighter who was down. A fight was now ended when a second could not bring his fighter back to a chalk square in the middle of the ring within 30 seconds.

John Broughton, the reigning champion from 1734 to 1758, did much to bring what was called “the noble science of self-defense” to prominence and greater respectability. It was he who first set down the above rules. He did so initially merely to regulate the matches at the school he had opened. Broughton invited high society gents to make the leap from sponsoring fighters to becoming pugilists themselves by enrolling at his academy. In order to attract “persons of quality and distinction,” gambling at the school was dispensed with and the fighters donned padded gloves or “mufflers,” as they were then known. The gloves were designed to prevent a gent from having to go courting with “black eyes, broken jaws, and bloody noses.” Broughton also traded on Enlightenment ideals when attempting to attract gentlemanly clients. His ads quoted from the Aeneid and called to Britons who “boast themselves inheritors of the Greek and Roman virtues” to “follow their example in conflicts of this magnanimous kind.”

Broughton also pushed boxing as a cure for “foreign effeminacy.” The sport was to him a “truly British art” that would preserve British identity and manliness. Many of Broughton’s contemporaries agreed with such a sentiment. Pierre Jean-Grosely remarked that boxing was “a special form of combat” not “merely congenial to the character of the English” but “inherent in English blood.”

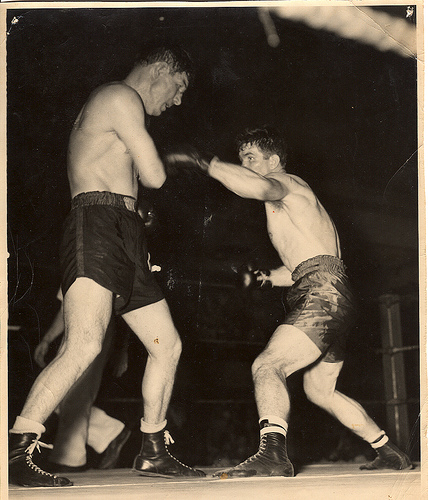

The Regency Period: Boxing’s First Golden Age

The 1780s ushered in the first golden age of modern boxing. The aristocracy’s interest in the sport, which had waned since Broughton’s heyday, experienced a resurgence. And England’s war with France spurred a sense of nationalism and a desire for men to take up this “truly British art.” The popularity of a series of fights between Richard Humphries and Daniel Mendoza also created widespread interest in the sweet science. These matches were some of the first to trade on ethnic rivalry, as Mendoza was Jewish and often known simply as “The Jew.” Mendoza’s fighting style also changed the nature of the sport. Pugilists had formerly stood toe to toe and simply slugged each other back and forth. Fighters would block shots but there was very little weaving, bobbing, and fancy footwork. No floating like a butterfly; just stinging like a bee. Mendoza brought in the dancing and the defense, making him highly successful, although also the object of scorn. Some spectators found this agile style to be “ungentlemanly.” Still, even the critics could admit it was more fun to watch than a straightforward pummeling. Trading on this battle between ethnicities and fighting styles, the bouts between Mendoza and Humphrey were wildly popular and fueled by boxing’s first war of words; each fighter sent taunting letters and brags to the newspapers before fights.

The British public’s enthusiasm for the sport led to the creation of numerous boxing schools and academies. Men were drawn to boxing’s promise to grant the athlete vigorous health and “courage to the timid.” They sought teaching in the art of self-defense in order to be able to hold their own when accosted by scalawags on the mean streets of London. Boxing was further sold as a way to defend one’s honor without resorting to the deadly tradition of dueling. The sport also dovetailed nicely with the Enlightenment’s burgeoning interest in equality. Boxers needed only fists and fortitude to compete, not special weaponry. Boxing was thus seen a great leveler in which all classes could compete on equal footing.

The Queensberry Rules

The dawn of the Victorian Age extinguished British ardor for the sweet science. In a time marked by the desire for all things moral and upright, pugilism’s violence, both in the ring and behind the scenes, rumors of thrown fights, and its association with gambling, doomed boxing to be labeled a “a low and demoralizing pursuit,” unfit for the interest of a respectable gentleman.

But the British weren’t through in adding their legacy to the sport. In 1867, the Queensberry rules were published, barring any wrestling moves, and essentially setting up the structure of modern boxing. Perhaps the most important of these new rules required pugilists to don gloves. The wearing of gloves drastically changed the nature of the sport. The bare knuckled fisticuffer stood upright, leaned back slightly, and held his arms with forearms facing outward. The gloved boxer leans forward and protects his face with his gloves. While gloves made the sport less brutal in some ways, they made boxing more dangerous and deadly by allowing fighters to punch with far greater strength (the bare knuckled boxer had to mitigate the impact of his blows for fear of winding up with a broken hand). The bones of one’s head are harder than those in the hand; thus, gloves helped the hitter and hurt the hittee. This accelerated the development of the more defensive style of boxing that Mendoza had begun, with a greater emphasis placed on bobbing, slipping, blocking, ect. Nonetheless, gloves greatly increased the frequency of knockouts and the battering boxers took often led to long term head injuries and the so-called “punch-drunk” syndrome.

The Queensberry rules may have made boxing more dangerous, but it also made it more entertaining, positioning the sport for commercialization and widespread appeal.

Boxing Moves to America

“The men who take part in these fights are as hard as nails, and it is not worth while to feel sentimental about their receiving punishment which as a matter of fact they do not mind. Of course,the men who look on ought to be able to stand up with the gloves, or without them, themselves; I have scant use for the type of sportsmanship which consists merely in looking on at the feats of someone else. “ –Theodore Roosevelt

As boxing waned in Britain, the seeds for the sport’s next Golden Age were being planted on American soil. In the early decades of the 19th century, boxing was barely on the American cultural radar. That began to change in the 1830’s when British pugilists, starved for matches at home, traveled to the States seeking other opportunities to fight. Bare knuckled showdowns, often between Brits and Irish immigrants or between American “natives” and the Irish, slowly began to attract Yankee interest.

In the latter half of the 19th century, boxing found advocates within the “muscular Christianity” movement which saw sports as a way to increase not only a man’s physical, but also his moral strength. Many churches ran their own gyms and supported fighters. Theodore Roosevelt, advocate of living the strenuous life and forever concerned about American men going soft and losing their manliness, was also a keen advocate of the sweet science. TR argued that “powerful, vigorous men of strong animal development must have some way in which their animal spirits can find vent.” As NY’s police commissioner he encouraged his officers to train in the ars pugandi, and he later sought its implemetation in the character-building program of the YMCA and in the training for men of the Armed Services. He himself boxed as a young man, throughout his years of college, and into his presidency, only stopping when a pugilist’s blow detached his left retina, leaving him blind in that eye (not one to let something like blindness dampen his fun, TR then took up jujitsu). Roosevelt especially recommended the sport to city dwellers who had limited space but wished to build up their strength and vigor.

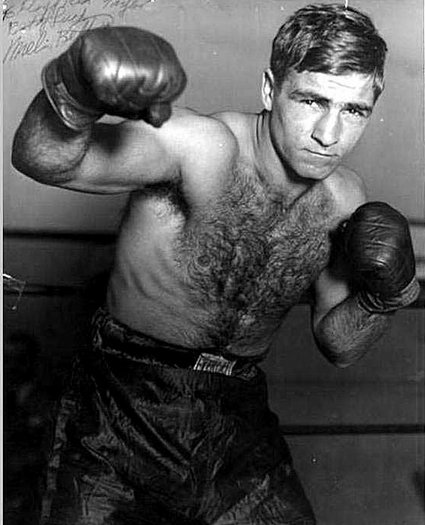

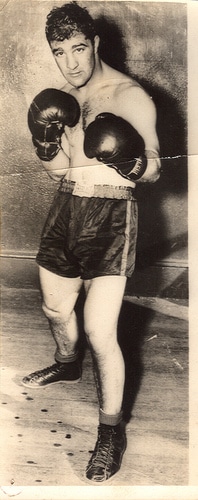

John L. Sullivan and the End of Bare Knuckle Boxing

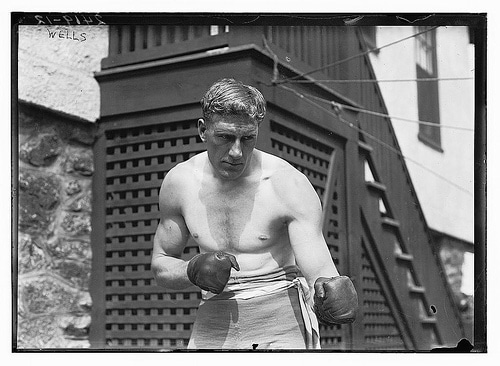

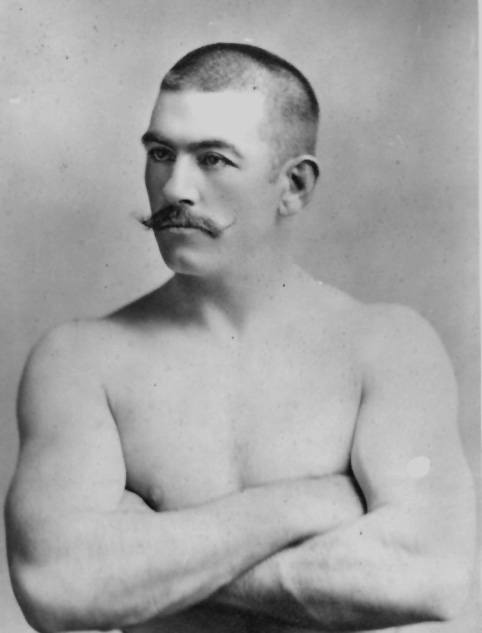

John L. Sullivan

“In this world, strength of a certain kind-matched of course with intelligence and tirelessly developed skills-determines masculinity. Just as the boxer is his body, a man’s masculinity’s his use of his body. But it is also his triumph over another’s use of his body. The Opponent is always male, the Opponent is the rival for one’s own masculinity, most fully and combatively realized….Men fighting men to determine worth (i.e., masculinity) excludes women as completely as the female experience of childbirth excludes men.” -Joyce Carol Oates

The man that would truly turn the corner of American boxing interest was John L. Sullivan. Born in 1858, Sullivan straddled the world of bare knuckle and gloved boxing, and helped to forever secure the popularity of the latter. Nicknamed the Boston Strongboy and His Fistic-holiness, John L. Sullivan would be bare knuckle boxing’s last champion and the first heavyweight champion by the new Queensberry rules.

Sullivan’s boxing prowess and colorful personality made him the nation’s first sport’s celebrity. Critics thought he was a drunken lout, but others felt the champion was a masculine, rough and tumble breath of fresh air in the feminized and button-up Victorian age. Sportswriter Bert Sugar said, “Maybe after George Washington, he was our first icon: the biggest thing we had between the Civil War and the Spanish-American War in any field. He was a hero.”

While often pictured as a bare knuckled boxer (that’s him in the AoM header), Sullivan fought the vast majority of his fights in gloves. His preference for gloves gave the sport new respectability and popularity. Boxing soon became legal in states where it had previously been outlawed.

As the sport rose to prominence in the States, its popularity continued to decline in England. Brits waxed nostalgic about their Golden Age and saw boxing’s ascendancy in America as another symbol of the way in which that country was eclipsing them in power and growth. Like many Britons, Arthur Doyle linked his country’s loss of dominance in the sport with what he perceived to be a parallel drop in manliness. When Doyle chose to have boxing figure prominently in his novel Rodney Stone, he was asked by his publisher, “Why that subject of all subjects on earth?” Doyle answered, “Better our sports should be a little too rough than that we should run the risk of effeminacy.” Indeed, in the book Stone looks back at boxing’s golden age longingly:

“The ale drinking, the rude good-fellowship, the heartiness, the laughter at discomforts, the craving to see the fight-all these may be set down as vulgar and trivial by those to whom they are distasteful; but to me, listening to the far off and uncertain echoes of our distant past, they seem to have been the very bones upon which much that is most solid and virile in this ancient race was molded.”

The Rise of Professional Boxing

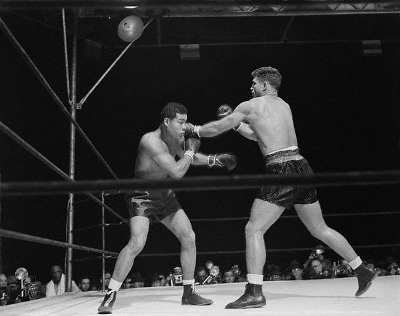

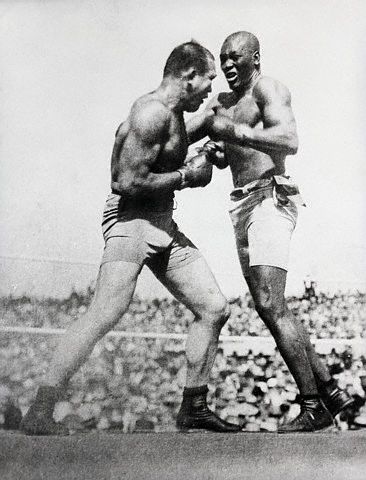

Jack Johnson battles James J. Jeffries, 1910

“The psychologist Erik Erikson discovered that, while little girls playing with blocks generally liked to create pleasant interior spaces and attractive entrances, little boys are inclined to pile up the blocks as high as they can and then watch them fall down: “the contemplation of ruins,” Erikson observes, “is a masculine specialty.” No matter the mesmerizing grace and beauty of a great boxing match, it is the catastrophic finale for which everyone waits, and hopes: the blocks piled as high as they can possibly be piled, then brought spectacularly down.” -Joyce Carol Oates

Up until 1920, prize-fighting was in a period of flux, legal in some places and not in others. The brutality of the sport did not concern the states, it was boxing’s connection with gambling and corruption which had government officials keeping it at bay.

To skirt the rules, matches were often held on islands and barges or by hastily created boxing “clubs” in which one could pay to become a “member” and thus watch the fight. These “clubs” were often sponsored by saloons, and bars soon became epicenters of the sport. The saloon was already popular as Jack London observed, as a “place where men believed they could escape from the narrowness of women’s influence into the wide free world of men.” Boxing merely added to this existing appeal.

Boxing matches of the early 20th century often traded on ethnic and racial animosities to promote fights. This dimension of boxing worked to catapult Jack Johnson to fame, when he became the first black man to become the heavyweight champion of the world in 1908. As soon as Johnson won the title, America began a frantic search for find a “great white hope” to dethrone him. Johnson picked off several potential “hopes” before facing undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries. Jeffries declared that he had come out of retirement “for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.” The fight, advertised as “the ultimate test of racial superiority,” proved a dark day for white supremacists.

Triumphant in the ring and provocative and flamboyant outside of it, Johnson was scorned by whites and beloved by African-Americans, who celebrated him as a hero of the race. He was one of the most famous and infamous celebrities of the time, and his high-profile career helped boxing gain an ever larger following.

Listen to our podcast on the rise and fall of the American heavyweight:

Boxing in the Golden Age of Sports

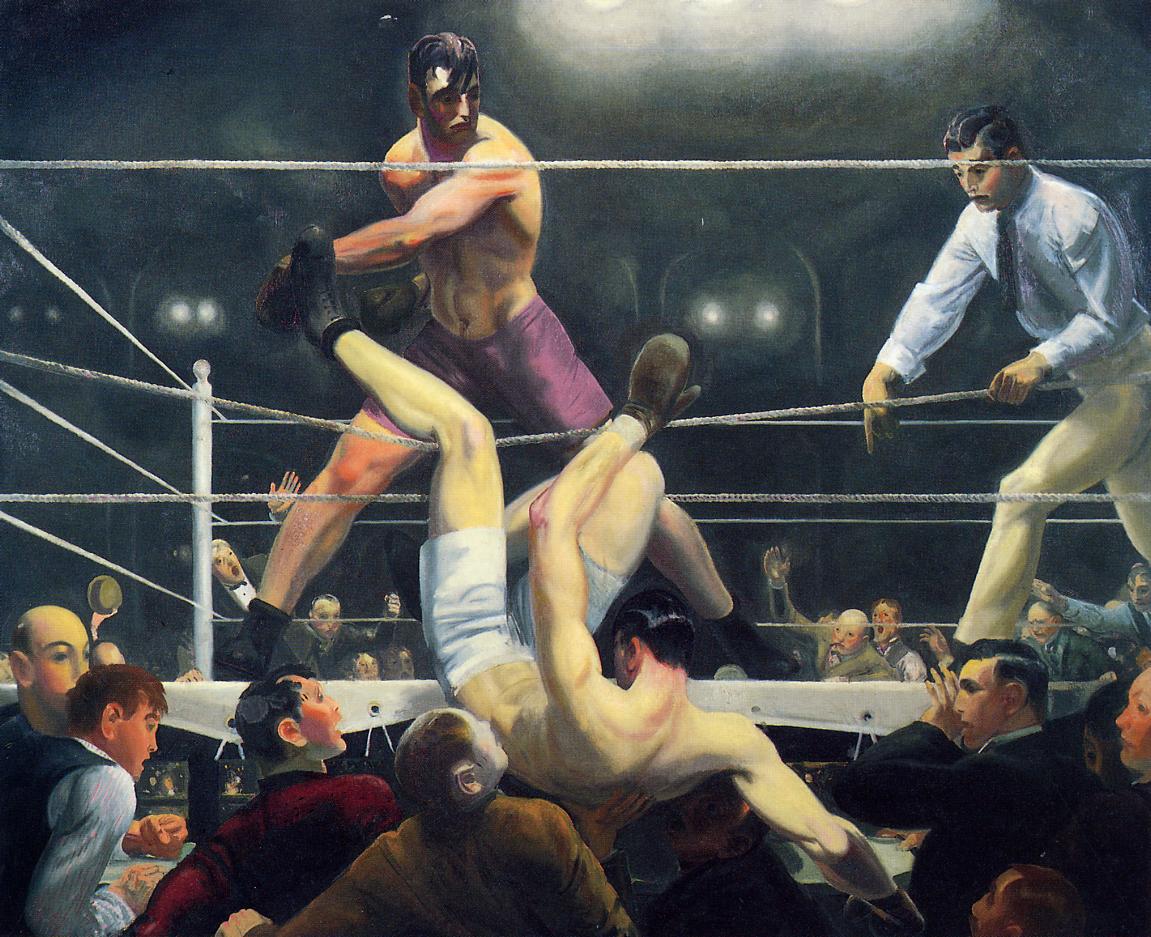

Dempsey and Firpo by artist George Bellows, 1924

The 1920’s are often cited as the most sports-crazy decade in American history. Decades before, the frontier had closed and been eulogized by Frederick Jackson Turner, and Americans feared that the hearty, resilient pioneer character of the country was fading away. The playing field thus became the new “frontier” to which Americans looked to find rugged individuals who reassured them that American grit was alive and well.

Jack Dempsey fit this bill. Born in Colorado and raised poor, Dempsey was an old fashioned “self-made man” with a fighting style that was brutal, direct, and efficient. After spending many years dispatching opponent after opponent, Dempsey captured the heavyweight title by pulverizing Jess Willard, who had previously taken the belt from Johnson.

But it was his bouts against Irish-American Gene Tunney which would become legendary. Dempsey first fought Tunney in 1926, before a crowd of 120,000 spectators. The fight was promoted as a battle between two different kinds of manliness: Tunney was the intellectual, clean-living, Marine of “self-improving and self-controlling masculinity,” while Dempsey was a rough and tumble symbol of “untameable virility and independence.” Tunney won the bout, and a rematch was set up a year later in Chicago. The fight simultaneously broke a record for the first $1 million gate and the first $2 million gate in entertainment history. The fight was not only watched by over 145,000 spectators at Soldier Field, but new radios allowed millions of Americans to tune in and listen as Tunney once again triumphed over Dempsey (although not without some controversy over the “Long Count“).

The Brown Bomber and Radio

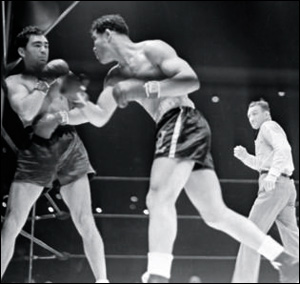

Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, 1938

“Some time ago one of the southern states adopted a new method of capital punishment. Poison gas supplanted the gallows. In its earliest stages, a microphone was placed inside the sealed death chamber so that scientific observers might hear the words of the dying prisoner….The first victim was a young Negro. As the pellet dropped into the container, and gas curled upward, through the microphone came these words: “Save me, Joe Louis, Save me, Joe Louis, Save me Joe Louis…”

After Tunney retired in 1928, boxing enthusiasts felt that another of the sport’s golden periods had come to a close. The heavyweight champion title passed through many hands in the ensuing decade. A.J. Leibling, the masterful sportswriter and boxing enthusiast, called these years boxing’s “Dark Ages.” This brief dark “age” was ended in 1937 by boxing’s next big celebrity: Joe Louis. Louis snatched the title from Depression-era hero, James J. Braddock, the “Cinderella Man.” Louis then held the title for 12 years.

The proliferation of radio was a huge boost to boxing and garnered the Brown Bomber fans the all over the country. People would gather around the radio in stores, homes, and churches to listen to his fights. As Miles Davis recalls, “We’d all be crowded around the radio, waiting to hear the announcer describe Joe knocking some mother****r out. And when he did, the whole goddamn black community of East St. Louis would go crazy.”

The Brown Bomber’s bouts are arguably the best examples of the way in which boxing can transcend the confines of mere sport to take on greater cultural meanings. Louis fought Primo Carnera in 1937, shortly after he had been photographed giving a fascist salute. Then, in 1938, he took on Max Schmeling, who had previously defeated him. Schmeling was a German fighter, touted by Goebbels and Hitler as a prime example of Aryan supremacy. The fight thus took on nationalistic overtones. FDR invited Louis to the White House before the fight, and feeling his biceps, said, “Joe, we’re depending on those muscles for America.” Joe’s muscles knocked out “Hitler’s pet” (as dubbed by Richard Wright) in little over 2 minutes. For whites, the victory symbolized the supremacy of American democracy over authoritarian fascism. For blacks, Louis was, like Jack Johnson before him, a hero of the race. A decade before Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, Louis was breaking both noses and racial barriers. After the Schmeling victory, 500,000 African-Americans took to the streets of Harlem, dancing, celebrating, and shouting “Heil Louis!”

Boxing in the Age of Television

Unlike sports like baseball with its giant playing field, large cast of characters, and tiny ball, television was an ideal medium to broadcast boxing. The action was easy to follow and the two dueling opponents fit nicely into one’s screen. Thus, during the late 40’s and 1950’s, boxing dominated this nascent medium, flickering on television screens almost every night of the week. While television brought the sweet science to a much wider audience (fight nights attracted 31% of the primetime audience), purists lamented its perceived drag on the sport. For them, the beauty and power of pugilism could not be felt through a tiny screen. One had to be there ringside, smelling the sweat of the combatants, and feeling the electricity of the crowds. After all, quipped A.J. Liebling, watching at home prevented you from “telling the fighters what to do.” More than that, Liebling lamented the way in which televised boxing was hurting the vibrancy of the live variety. With free boxing being televised every night of the week, attendance at live fights dropped significantly. This “knocked out of business the hundreds of small-city and neighborhood boxing clubs where youngsters has a chance to learn their trade and journeymen to mature their skills.” Television’s’ frequent broadcasts required a constant stream of fresh boxers, dipping into a pool of pugilists who were not yet experienced enough to go toe to toe with a bruiser for 12 rounds. As a result, several boxers expired as the cameras rolled.

When Boxers Were Kings

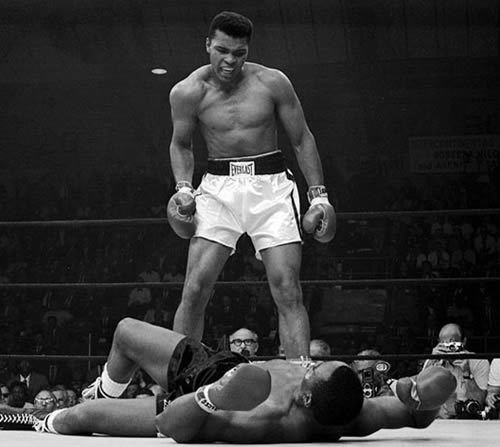

Muhammad Ali stands over a fallen Sonny Liston, 1965

“Boxing is for men, and is about men, and is men. A celebration of the lost religion of masculinity all the more trenchant for its being lost.” -Carol Joyce Oates

Sugar Ray Robinson, arguably the best pound for pound boxer in history, was the next fighter to captivate boxing fans until his last title win in 1955. Though Robinson was prolific, he never quite became a cultural institution the way Dempsey or Louis had. And after his career declined, boxing once again hit a stagnant period. These doldrums were broken by the “Poet and Pedagogue,” Cassisus Clay. Whether you loved him or loathed him, Clay was handsome, charismatic, and exciting to watch in the ring. His penchant for bravado, prophesy, and poetry charmed many a fan back into the boxing fold. Clay’s transformation into Muhammad Ali, his affiliation with the Nation of Islam, and his refusal to serve in Vietnam made him a hero of liberal blacks and whites alike. Conservative boxing fans meanwhile gravitated to Ali’s rival, Joe Frazier.

The meeting of these bitter rivals in 1971 was dubbed the “Fight of the Century,” and it lived up to its billing, with Frazier knocking down Ali with a fierce hook in the final round. These two pugilists were brilliant fighters, but they weren’t alone in trading the title back and forth. George Foreman was a third character in the era’s holy trinity of boxing greatness. With such competition, no fighter could hold the title for long. Thus in 1973, in one of boxing’s greatest upsets, Foreman downed Frazier with an uppercut that knocked him off his feet during the Sunshine Showdown.

Foreman would pick up two more knockouts on his way to his next title defense fight with Muhammad Ali, bringing his total KO’s to 37. And the odds for 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle were heavily in this prodigious puncher’s corner. The historic bout, staged in Zaire in 1974, would turn out to be another monumental upset. Ali exhausted Foreman by giving him the “rope of dope” treatment. Then, in the eighth round, he dropped Foreman to the canvas.

The legendary bouts of the 70’s were not quite over yet. Frazier and Ali squared off in 1975 for their third meeting, the Thrilla in Manila. In 100 degree heat, these rivals duked it out. Ali had been mercilessly taunting Frazier for some time, and the acrimony between the men was manifest as they ground through 14 rounds. Frazier’s trainer would not allow his fighter to come out for the 15th round, and his corner threw up the sponge.

While Ali’s career was not quite finished, the Thrilla in the Manila was certainly the high point of this legendary time of pugilism. Boxing would see a resurgence in the coming of fighters like Sugar Ray Leonard and Mike Tyson, but the bout marked the end of what many consider the greatest and final golden age of boxing.

Boxing Today

I wonder if the American audience in this current day and age wants to deal with something as raw as the sweet science. Like jazz music, what seems straightforward, easily understood, and mastered is, well, not. -Bob Margolis, amateur boxer and jazz musician

Boxing is nowhere as popular as it once was during the time of Ali, or even Tyson. Its place in popular culture has been weakened by several factors. First, for most of boxing’s history, it did not have to compete against many other sports; even in the 1920’s the baseball and football seasons were shorter and there was no NASCAR or NBA. Today, boxing must attempt to carve out a niche alongside these other sports, not to mention compete against the burgeoning popularity of MMA and the UFC. And unlike many sports, boxers do not compete in long seasons, fighting only several times a year. The sweet science has been further weakened by boxing’s mutliple governing boards and “Alphabet titles.” These numerous divisions make it hard to call one fighter the absolute champ, and there hasn’t been a truly break-out star since Mike Tyson.

What has perhaps weakened boxing the most, however, and it is a thing that has always been it’s achilles heel, is a flagging public appreciation for the complexity and poetry of the sport. While often simplistically painted as a straightforward and barbaric pursuit, nothing could be farther from the truth. It may contain vestiges of our primitive impulses, but it has also been called a “science” for good reason. While many see today’s fighters as not the brightest bulbs, history shows that its allure has attracted men from all classes, from lower-class ruffians to aristocrats and artists (the list of authors who have been drawn to writing about boxing but who also boxed themselves is legion: Hemingway, London, Eliot, and Doyle to name a few). Those who really take the time to understand boxing, know it to be a brutal art. It is a chess game, full of finesse and strategy. And so we plan on doing more articles in the future to further your understanding of the sweet science, in hopes of doing our part to usher in yet another golden age of pugilism.

Sources:

Boxing: A Cultural History, by Kasia Boddy

On Boxing, by Joyce Carol Oates

.