When you picture a gunfighter, you probably think of a Hollywood cowboy — spurs jangling, six-shooter on his hip, squaring off at high noon in a dusty frontier town. But gunfighters weren’t just products of Hollywood. They were real men who lived and died by a code: one rooted in a particular sense of honor.

My guest today is Bryan Burrough, author of The Gunfighters: How Texas Made the West Wild. We dig into the true story behind America’s gunfighting era — how it grew out of the South’s dueling culture, was intensified by the violence of post–Civil War Texas, and spread across the frontier via the cattle drive. We explore why so many gunfights had less to do with crime and more to do with reputation, why the Colt revolver transformed personal conflict into deadly spectacle, and how young men came to see violence as a rite of manhood. Along the way, Bryan also explores how gunfighters went from frontier figures to pop culture icons — and which films, in his view, captured their essence best.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Johnny Ringo

- John Wesley Hardin

- Wild Bill Hickok

- Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

- Fight scene in Gangs of New York

- AoM Article: The Best Western Movies Ever Made

- AoM Article: 21 Western Novels Every Man Should Read

- AoM series on honor, including What Is Honor? and Honor in the American South

- AoM Article: The Rough and Tumble

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. When you picture a gunfighter, you probably think of a Hollywood cowboy. Spurs jangling, six-shooter on his hip, squaring off at high noon in a dusty frontier town. But gunfighters weren’t just products of Hollywood. They were real men who lived and died by a code, one rooted in a particular sense of honor. My guest today is Bryan Burrough, author of The Gunfighters: How Texas Made the West Wild. We dig into the true story behind America’s gunfighting era, how it grew out of the South’s dueling culture, was intensified by the violence of post-Civil War Texas, and spread across the frontier via the cattle drive. We explore why so many gunfights had less to do with crime and more to do with reputation, why the Colt Revolver transformed personal conflict into deadly spectacle, and how young men came to see violence as a right of manhood. Along the way, Brian also explores how gunfighters went from frontier figures to pop culture icons, and which films, in his view, captured their essence best. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/gunfighters. All right, Bryan Burrough, welcome to the show.

Bryan Burrough: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you recently published a book called The Gunfighters: How Texas Made the West Wild, and this is all about the Old West gunfighter that you see in Old Westerns and TV shows. I’m curious, why did you do a deep dive into the gunfighter?

Bryan Burrough: Because I felt like the time was right. This was a field of study, if you want to call it that, that was probably at its high-water mark 50, 60 years ago in the ’60s and ’70s. And while there had been books on individual gunfighters, in fact, there’s a new Jesse James book pretty much every year, a new Billy the Kid every two or three years, I kind of felt like it had been quite a while since anyone had come in and really taken a fresh look at the entire subject, the entire field, and tried to tell the whole story of this gunfighter era that took place in America on the frontier after the Civil War. And I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to say new, but I just felt like it was time to freshen up the canon and that I could take a big… I thought I could swing for the fences on this one, and so I kind of did. It kind of went out over my skis a little bit to badly mix my metaphors. And the reception, as you know, has been very generous and very surprising.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think what you do in this book, I really appreciated this, is you provide the context of why there was this period in American history where you had guys shooting at each other. Let’s talk about this. What makes a gunfight a gunfight? And what makes a gunfighter a gunfighter?

Bryan Burrough: Well, typically the way you would differentiate is a gunfighter is anyone, I think, widely defined, as anyone who had an exchange of gunfire on the American frontier that did not involve the military, so not a soldier or Native Americans. So this is exclusively civilian gun violence. It could be a sheriff versus a bad guy. It could be two feudists. It could be two drunken cattlemen. It was civilian gun violence. But having said that, it comes in every way, shape, and form. I guess the one thing that makes a gunfight a gunfight is if there is an exchange of gunfire as opposed to, you know, for instance, Jesse James, most of the people he killed he just executed. So there is a difference between a murderer and a gunfighter, and I think generally that’s pretty clear. If you think about the classic gunfight, what most of us know about this from movies, and the classic one that came up in Westerns in the middle of the last century was, you know, two men standing alone in the middle of a sandy street in a small town, and then they draw and they shoot. And while that’s not unknown, I can maybe point to 10 or 15 actually like that.

In fact, Old West gunfights are not typically different in style from any gunfight today. I can point to you gunfights on horseback, gunfights where one guy was laying down and the other was standing up. I got one where one guy shot another while he was down in a well. I mean, it just happened in every way, shape, or form. But the rarest was probably that classic two men squaring off, although ironically, the one that I opened the book with and the first nationally recognized gunfight, what really began to make the gunfighter a thing, was very much that type of classic cliche gunfight, two men in the street. In this case, it involved the famous gunfighter Wild Bill Hickok in his first nationally recognized gunfight in July of ’65 in Springfield, Missouri. And it was very much in the style of an old duel like from the Old South, where they came together in the middle of the square in Springfield, Missouri. The fight was over a gambling dispute with townspeople lined up on both sides, and then they draw simultaneously. And of course, Hickok is the victor.

And shortly thereafter, an Eastern rider for a big magazine found out about this, wrote about it, and it was really the first moment where Americans became aware, oh, not only are there people shooting each other out on the frontier, but that this is, it somehow struck a chord, something in the American character that really, you know, at a time where people were shooting each other on the streets of Boston and Baltimore every night, nobody cared other than it being a crime. This seemed to be something different. And the gunfight, the frontier gunfight, has fascinated Americans really for 160 years ever since. I mean, we’re still talking about this stuff 160 years later.

Brett McKay: How do you demarcate the gunfighter era? When did it begin and when did it end?

Bryan Burrough: Well, one big challenge for me going into this, of course, is that how do you write a book about gunfighters when they’re all over the place? This goes on for, you know, decades. And most of these, you know, Jesse James has nothing to do with Billy the Kid, who has nothing to do with John Wesley Hardin. And so the first thing I did was demarcate my time. So I grandly called what I dubbed the gunfighter era from July of 1865 until 1901 when Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid famously got on that freighter for South America. The ending of the last brand name outlaw seemed like an appropriate place to end it. And so then the question became, how do you tell that all as a single story? And I think I found a way that I could actually hold it all together as one story.

Brett McKay: And how many gunfights were there during that era, you think?

Bryan Burrough: It would all depend on how you define gunfights. I honestly have no idea. Clearly, it’s in the hundreds. I know Bill O’Neill, a well-known Texas historian. In fact, I believe he was the state historian for a while. I want to say he came up with like 580 what he called significant gunfights. And again, very difficult to explain to you what significant is, but in large part, they’re the ones that made the newspapers and thus the history books, and typically more than one newspaper suggesting some public interest. So certainly things like the gunfight beside the O.K. Corral starring Wyatt Earp, certainly anything involving Billy the Kid, John Winsley Hardin. In general, the notable gunfights, what I call marquee gunfights, are those that made more than one newspaper at the time.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. Okay, so you mentioned that all these gunfights, they happened all over the place. They seemed like they weren’t connected. So your challenge was trying to figure out, okay, what is the connection? And your connection that you found was Texas, where you live, your home state. And what I took away from the book, Texas contributed several factors that gave rise to the gunfighter. And a big part of that is cultural. So tell me about this cultural component of the gunfighter. You talk about how they’re developed after the Civil War, or even before the Civil War, this idea of Texan honor that developed out of Southern honor. So tell us about that. Tell us about the Southern honor code, and then how did that develop into the Texan honor code? And then we can talk about how that led to the gunfighter.

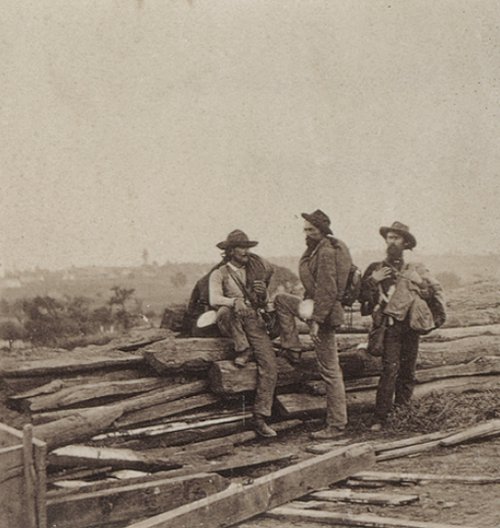

Bryan Burrough: Sure. When you’re looking at a way to explain why all this happened, the only thing that I could figure out to do was to understand why it happened, why it happened there, and what were the factors that caused all these gunfights. And I remember one of the first times it really hit me was in reading accounts of that first Hickok gunfight in 1865. And they were ostensibly fighting over the other guy took Bill Hickok’s watch as a gambling debt, and Hickok wanted his watch back. And later somebody said, why on earth would you kill a man over a watch? And he said, I’m not killing a man over a watch. This was about my honor. This was a challenge to my honor. I’d read stuff like that before in Western literature. And I happened to be from the South and happened to be from Texas. And that struck a real chord to me. And just immediately I realized, well, when was the only time in American history before the gunfighters after the Civil War that a group of civilian men were famous for shooting each other? And it was in the dueling culture in the antebellum South from the 1790s or so into the 1840s. Duels were a very big thing in the South.

And what mattered to me was less the formal structure of the duel, because obviously we didn’t have a ton of duels in the Old West, but rather the factors that caused it. There’s this thing that historians write an awful lot about in the antebellum South, and it’s the male honor culture. And that is, you know, it calls for things that you might expect, you know, to be brave and kind to women and kind to horses and such. But the part that matters for our story is that any time that a Southern male in that time period was challenged, if he was told that he was ugly or his wife was ugly or his horse was ugly, you know, he had an opportunity and in many cases an obligation to respond with force, even deadly force. And that’s what led to these duels. And what you find as you follow that culture as it moves west with the South into Texas, Texas became another Southern state, but Texas was different. It was the only Southern state that had not one but two violent frontiers, the Mexican border, of course, but also we forget the Native American, the Comanche frontier, which split the state in half on a diagonal into the 1870s.

It made the Texan particularly adept. It was a martial culture. They were adept from the beginning with guns. It was the Texans, the Texas Rangers, to be sure, who initially discovered and popularized the first Colt revolvers. You know, it was Texans who made it a thing, but it really wasn’t until the 10 years after the Civil War, when Texas was engulfed with rebellion against the federal government, that that type of hyper-violent ethos really rose to the fore, where it was just Texas was, during Reconstruction, I think just about every academic study puts it this way, by far the most violent of the Southern states. You can find academic analyses that will say that the decade of civilian violence in Texas after the war may have been the bloodiest period of civilian violence in American history. And what I posit is that it made the Texan a little bit of a different animal. If you go and look at the marquee gunfights out there, Brett, I’m saying 60, 70% of them involve a Texan in some way. And what I had not understood, what confused me initially is, well, what were Texans doing having gunfights in Arizona, in New Mexico, in Wyoming, in Nebraska?

And that’s when I discovered the thing that spread Texas culture and this Texas kind of hyper-violence across the frontier was the open ranged cattle industry. It was a business that began in Texas and that thrived in Texas after the war. Texans pretty much had a monopoly on beef cattle for a few years. And what began to spread Texas cattle and Texas cattlemen, Texas cowboys across the frontier, of course, was the need to get to Northern markets when they began driving these cattle up the cattle trails, up the Chisholm Trail, most famously, into Kansas, which really became kind of the beginning of this gunfighter era when gunfighters began to get national attention.

Brett McKay: Yeah, there’s a lot to unpack there, but honing in on this honor idea, I think this is very foreign for a lot of modern listeners because, I mean, this idea of honor that these guys had in the South, and you see it somewhat in the North, not as much, but it really took hold in the South. It was all about protecting your reputation. I mean, that’s what it was. It was all about your reputation as a man. And if your reputation was somehow called into question, you had to defend it with violence. And there’s a theory that the reason why the South has a particularly strong notion of honor, I think, was it Richard Nisbet, his book, The Culture of Honor?

Bryan Burrough: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Talked about how a lot of people in the South, they came from these shepherding cultures in Scotland.

Bryan Burrough: Scotland and Ireland, especially.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Bryan Burrough: Those who work around livestock, it’s always been violent cultures, in part, the need to dissuade thieves. And for whatever reasons, much of it becomes wrapped up in honor. You can read so many explanations of why Southerners became obsessed with honor. A lot of historians seem to believe it has to have something with slavery. You can read people that say it has something to do with the heat. I come down with the feeling that it basically arose from the planters’ class, the wealthiest class in the South, where we had something in the South that we never had in America, which was the idle rich, an entire class of idle rich for whom Black people, slaves, did most, if not all, of their work. And so in a need to kind of differentiate themselves from those below them who worked, they modeled themselves after the aristocrats of Europe, for whom honor had been sacrosanct for hundreds of years. And that’s kind of my feeling on how Southerners became obsessed with honor. And it filtered down through the classes. If you wanted to move up, you needed to have honor.

And this happened in a world where not a lot of people had college degrees or educations that they could talk about or financial statements. And in a world where everybody kind of looked the same, honor became the way you measured people, the way you measured men. And as silly as it may sound to our ears today, if someone went up to you in New Orleans in 1844 and pinched your nose or called you ugly or made a remark about your children, you were expected to lash back in some way, shape, or form. And I think it was the development of that culture that migrated into something different, something even more violent via Texas on the old West frontier.

Brett McKay: Yeah, my take on it was the honor code in the South. And again, you saw it somewhat in the North, but it was really pronounced in the South. The way you protected your honor differed amongst classes. So amongst the upper class in the South, you would follow the codice duello, like the dueling code.

And it was designed basically to prevent violence. Like there’s all these different protocols you went through. You had a second, you try to do some negotiation. And then oftentimes you just show up and like shoot your pistol in the air. And you called it good. The lower class, they tended to just like, they didn’t use weapons. They didn’t follow the formal dueling code. They would just oftentimes engage in like, they called it the rough and tumble.

Bryan Burrough: I mean, I’m telling you, fist fighting and wrestling back in those days was a different thing. I mean, you’re talking about gouging out eyes and ripping people’s mouths. I mean, several states had to pass laws against eye gouging, if you can imagine. Anyway, this whole honor thing seems to have come out of the Revolutionary War when American officers kind of got close and personal with their British and French counterparts for whom honor was a very big deal. But it stopped in the North, as you point out, and most people believe that was about the Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton duel in Weehawken, New Jersey in 1803. After that, duels all but disappear from the North. And yet, they not only don’t disappear in the South, they’re all but embraced. I mean, you can point to any number of known people, Andrew Jackson, Sam Houston, Abraham Lincoln, who all either involved in duels, you know, shot people in duels, or in Lincoln’s case, he managed to talk himself out of one. Duels were not, like, I think we look back now and think, oh, that’s kind of a lunatic fringe type of deal.

But if you look at the people who are engaged in duels, who, you know, put out public notices, they were often politicians and people involved in public life for whom an assault on their honor was kind of widely known. If you were an up-and-coming congressman in St. Louis, and somebody, you know, talked bad about you, I mean, you were challenging them to duel. Missouri was, Missouri and St. Louis was kind of the northern boundary of all this.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And for our listeners, if you want to see an example of like a lower-class notion of honor, like the rough and tumble that we were talking about, that wrestling, like no-holds-barred wrestling, there’s a great scene in the Gangs of New York where the DiCaprio character, who’s from Ireland, he first meets Bill the Butcher, and there’s like some other, one of Bill the Butcher’s heavies is there, and there’s some sort of insult or slight, and then they just immediately take off their coats and they start punching each other, but then there’s some like fish hooking and things like that. I’m like, that’s an old-school Civil War notion of honor amongst the working class.

Bryan Burrough: Yeah, I had forgotten about that. That was a very good example of it, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Okay, so, and then this notion of honor, it moved to Texas, and I think what happened in Texas, in the sort of notion of Texan honor, it got democratized, I think, significantly. It wasn’t just like the aristocrats who were protecting their honor, it was these guys who had herds who felt like they needed to maintain their reputation for violence so people would just not mess with them. And then you see this introduction of, you mentioned earlier, the Colt revolver. So there’s a technological component to the gunfighter. Tell us about that. How did the Colt revolver change the game in the Old West?

Bryan Burrough: There is no gunfighter. There is no gunfighter age without a revolver. If you think of it, back in Antebellum days, when they would have duels, typically it would be with single-shot pistols. So bang, the other guy goes bang, and then everybody takes 15 seconds to reload. You can’t exactly kill a lot of people in that way, but when you had a six-shot revolver, you could do an awful lot of damage. We sometimes forget that when Colt was kind of a nobody, a rich kid out of Massachusetts who was fascinated with tinkering and thought he could make a revolving gun. But when it was introduced for the first time in, I want to say 1837, it was a complete flop. In fact, five years later, Colt is out of business and no one’s using revolvers. And then out of nowhere, a young officer named Jack Hayes in the Texas Rangers, who spends much of his time on the Comanche frontier fighting Native Americans, stumbles on a shipment of them that was basically sitting in a warehouse. It had initially been sent, I love this, to the Texas Navy back when Texas had a Navy as an independent nation.

Jack Hayes took these revolvers, showed his men how to use them, and famously in 1844 at the Battle of Waller Creek, northwest of San Antonio, he was engaged with his crew of, I want to say 23, 24 guys against a group of Comanche that was said to number around 100. And for the first time, the Rangers charged into the Comanche firing the revolvers. And in the ensuing fight, 23, 24 Comanche were killed and only one Ranger. And the great takeaway quote afterwards, years later, the chief who had been involved there said, I shall never fight Jack Hayes again, for he has a bullet for every finger on his hand.

Brett McKay: And then how did the Colt change the game for gunfighters?

Bryan Burrough: Well, first off, you don’t notice a huge difference immediately countrywide until the years after the Civil War when you can talk about how the war influenced gunfighters and these people doing this violence to each other out on the frontier. And common sense tells you the war must have had something to do with it. It’s often been speculated that many of these gunfighters must have been suffering from something like PTSD, which is compelling and probably correct, but it still has to remain speculative because we don’t have anybody at the time, you know, blaming, I’m sorry I killed those four guys, I had a bad day at Gettysburg. But what you can point to about the war influencing violence is that in 1865, 1866, something on the order of 1.3 million handguns were auctioned or given away by the federal government after the war. And so for the first time, what we call today as open carry, while not unheard of before the war, you can find memoirs in which people say, oh, I saw a man wearing a gun on his hip in Georgia in 1815. It happened. But what becomes clear is that after the war in the 1860s, it becomes commonplace, such that people are just kind of stunned that men across the South, across the frontier, are wearing pistols with no more thought than the way they used to wear a necktie or their glasses.

And one of my favorite memoirists out of Missouri, in a reference to that rough and tumble type of style, says that type of problem resolution is gone now. People here handle such things with a pistol in a much quicker and more efficient fashion. And that’s really the dawn of the gunfighter era.

Brett McKay: We’re going to take a quick break for your words from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Okay, so you had this notion of honor instead of a duel with these elaborate procedures and rituals. You just had guys who were like, let’s just take care of it now. And they were all heavily armed. They’re all carrying pistols. Some guys had two pistols on them. It’s just everyone was armed in Texas and in the frontier. Pretty much. Another aspect or another way technology contributed to the rise of the gunfighter was the telegraph and mass media. Tell us about that.

Bryan Burrough: It’s funny. I think most people that look at this think that gunfighting and gunfighters were somehow a creation of the media, a creation of dime novels and pulp fiction. In fact, the gunfighters type violence that I’m writing about here and that we see in movies was very real. I think what telegraphs and the media allowed is for the fascination with this phenomena, which, by the way, did not begin in the East. It begins in the communities where these things happen. You can read it in the local newspapers. All the pulp fiction and dime novel writers did was pick up on something that was initially very popular in the West. You can read one of my favorite stories about this is from very early in the game when Mark Twain, as a young writer, went out to Nevada during the Civil War to become a journalist. And on the way on these stagecoaches, all anybody ever wanted to talk about was a certain gunfighter, a guy named Jack Slade, who was a local legend.

And that was months, if not years, before anybody uttered his name back East. So I think that the media, and we see this especially with Hickok’s creation, you know, the media broadcast this legend, but they don’t create it. I think that’s where a lot of cynics want to say they created it. And I would argue, no, this was a genuine organic phenomena that they picked up because it fascinated Americans. For some reason, and we can speculate why, you know, this type of behavior really struck a chord with Americans. So there would still have been gunfighters, but I’m not sure they would have become the American archetypes they did if not for media.

Brett McKay: Why do you think it struck a chord with Americans at the time?

Bryan Burrough: I think it has to do with the fact that the American West really became the American origin story. You know, we can tell all the tales we want about George Washington and men in powdered wigs beating the British, and that’s clearly the actual origin story. But stylistically and in terms of values and behaviors that we might want to emulate, I’m not sure there was that many that people look to the the Revolutionary War to find. Instead, I think when people think about American values, when they think about the American dream, the American dream, as I define it, would be the idea that any person, certainly any man in America, can rise from humble beginnings and chart his own way. And nowhere was that more evident than on the frontier, where thousands of Americans went out, you know, and pitched a dent on a patch of dirt and tried to make something of themselves.

And it made the frontier, I think, kind of a cradle for the American worship of individualism, the idea that anyone can do it. And there’s something about the gunfighter who’s kind of the ultimate individual, isn’t he? You know, what’s more, what is more of an equalizer than a gun, where a man who’s 4’11 could kill a man who’s 7′ tall and a wrestler? The gunfighter became kind of a symbol, one of many probably, but a symbol, an abiding symbol of American individualism and of the American dream. That’s my theory, at least.

Brett McKay: So these gunfights are happening organically. Back East, they picked up on it, started writing about them in the paperbacks and the dime novels and the National Police Gazette was a big place where all these stories were published. I’m curious, I’ve heard that, kind of fast-forwarding and looking at another area of American history related to crime and violence, The Godfather, the movie The Godfather, I’m going a completely different stream here, but I’m going somewhere with this.

Bryan Burrough: I’m with you.

Brett McKay: Some people speculate that the movie The Godfather influenced the mob, the actual mob. Like these mobsters, they watched The Godfather, and they’re like, well, we got to act this way because that’s what it says in The Godfather. Did you come across anything like that where you see that with the gunfighter? Like there’s young men who are reading these dime novels, and they’re like, well, I got to carry my gun this way, or I got to do this so I can be like the gunfighters that I read about on the National Police Gazette.

Bryan Burrough: I know way too much about The Godfather, and you’re exactly right. I mean, the woods are so full of mafia guys, you know, back in the ’80s, ’90s, who talked about how, yeah, they needed to live that way. And you see exactly the same thing in the Old West. I can think of individual moments. For instance, Butch Cassidy in his second robbery in Utah, and I want to say 1896, which was very late in the game on the frontier. He had a partner named Elzy Lay. And I can remember in the middle of this robbery when one of the guys that they were robbing tried to make a move,Elzy Lay said to him something like, don’t pick up that gun or I’ll fill your belly full of hot lead. Like, who talks like that? The fact is nobody talks like that. It’s so clear that he got that from Pulp Fiction. He got that from a dime novel. But you also see that from the very beginning with the Texas cowboys who spread across the frontier, first to Kansas, but then to New Mexico and beyond. You can find memoirs. I’m thinking of Teddy Blue Abbott’s famous cowboy memoir.

And he talks about how he was yearning to get to Kansas so he could shoot someone, so he could prove his honor, so he could prove his manhood. You know, being involved in a gunfight was not something in that time, in that place, among those people that was something to be shied away from. It was something, in fact, that a lot of young men attempting to prove who they were yearned for and sought. And it’s one way that, you know, when you look at the behavior of Texas cowboys in the 1870s especially, I mean, there’s so many things where you’re like, really? They shot him over that? They shot him because he got jostled in a bar? They shot him because somebody, you know, beat him at go fish? They’re just silly things that caused gunfights. But if you take into this the context that many young men wanted to prove their manhood with guns, some of those silly gunfights make much more sense.

Brett McKay: Well, speaking of the cowboys, that was another factor that contributed to the rise of the gunfighter. It was an economic factor. You see the rise of the Texas cowboy and the Texas longhorn, the steer. How did the cattle boom from Texas contribute to the gunfighter?

Bryan Burrough: Well, the cattle boom took a southern honor culture that had been already, you know, pumped up to pretty new heights in Texas and added kind of the final block to the wall, if you will. And that is the Texas cattle business, especially as expanded into new areas in the 1860s and ’70s. So moved from South Texas into much of the rest of Texas, especially Central Texas, was legendarily violent because this was open range cattle ranching. So no barbed wire fence. The cattle range free. You put a brand on them and when it was time to go to market, you went and rounded them up. Well, obviously that made this industry especially prone to thievery, to theft of livestock. And so that’s the reason why Texas cattlemen, like generations of cattlemen before them, resorted to violence so readily. You know, often it was hanging. And this, by the way, played out in a dozen of kind of feuds across Texas in the decade after the Civil War, all of which dwarfed the body count of a feud like Hatfield and McCoy. This was probably eight of the 10 worst feuds in American history were around the cattle industry in Texas. And a lot of the violence was hanging, but much of it was also gunfights.

And especially as those behaviors spread across the West, that’s how you explain Texas cattlemen in gunfights pretty much everywhere you want to look in the West.

Brett McKay: And this is why you say, you know, Texas made the West wild. The cattle industry spread through what was an Indian territory up to Kansas, Abilene, Dodge City. And that’s why we had that famous gunfight in Arizona, the O.K. Corral. I mean, that was basically…

Bryan Burrough: I mean, Texans practically colonized New Mexico, Texas cattlemen. When you look at Arizona, I think Arizona went from, I want to say, 3,000 cattle in 1870 to 5 million in 1890, and all those were brought in by Texans. It’s funny, when you look at the outlaw gang that Wyatt Earp fought against in Tombstone that led to the famous gunfight beside the O.K. Corral, they were known as the Cowboys, usually spelled Cal hyphen boys, except from below the border where they stole many of their cattle, Mexican ranchers called them the Tejanos because so many of them were from Texas.

Brett McKay: All right, so the rise of the gunfighter, we’ve got the honor culture that morphed into Texan honor culture, the rise of the Colt Revolver, and then the cattle boom spread this violence across the American West. Something else I was struck by in your book, a lot of the gunfighters you highlight were gamblers. What was the connection? Why were so many gunfighters gamblers?

Bryan Burrough: Well, first off, almost everybody in the Old West was a gambler because there wasn’t much else to do. Keep in mind, no TV, no internet, no radio, nothing much to do but sit around and talk and drink and, oh yeah, play cards. So almost every main gunfighter I can think of, other than maybe Jesse James, who is not really a gunfighter, but that’s a story for another day, engaged in gambling as a pastime and occasionally as their profession. And there you could cite Doc Holliday, you could cite the Texan Ben Thompson and the Texan Luke Short as being kind of the three great gambler gunfighters. But you raise a question that perplexed me at the beginning, which is if you start to look at these marquee gunfights, you see a disturbing number of them involve arguments over gambling, which just didn’t make much sense to me. If you and I are sitting there playing five-card draw, Brett, and I throw out two fives and you throw out two fours, well, it’s pretty obvious I won. What is there to argue about? And then I started reading the histories on gambling, and it turns out that gambling on the frontier was a little bit different today.

And the reason it was so violent, I came to believe, is that, well, two things. One, Americans finally figured out that most gambling, certainly card-based gambling, was fixed, that people who did it professionally or did it often knew how to cheat. This was thanks to a riverboat gambler who in the 1840s came out and wrote a book about all the ways that gamblers could cheat and did. So everybody on the frontier was on the lookout for cheating, and cheating was endemic. And certainly any challenge of cheating, and that’s what an awful lot of the gambling-based arguments were about, was you cheated. Prove it. Well, here’s a gun. But if you were challenged to cheating, that was an acute challenge to your honor, and that led to a lot of gunfights, an awful lot of them. I mean, maybe, I don’t know, maybe 30%, 40% of the gunfights that I write about seem to have something to do with gambling.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I think it’s called giving someone the lie. It’s like when you accuse someone of lying.

Bryan Burrough: Ooh, I wish I’d known that. That’s a good line.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Let’s talk about some particular gunfighters that stood out to you. So a lot of these gunfighters, thanks to the dime novels, the pulp newspapers, they had a lot of hype around them. Like, well, this guy killed 30 men and this guy killed 50. If you look at the actual numbers, most of them maybe killed one or two guys. Some of them got up to maybe five. Out of all the gunfighters you researched and wrote about, which one actually lived up to the hype that they had?

Bryan Burrough: John Wesley Hardin of Texas, who of what I call the big five gunfighters, meaning the most famous, those would be Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and the least known is John Wesley Hardin , who very much is a transition figure from kind of exclusively Texas violence to violence out on the frontier. He was just another kid in rural Texas until he killed a black man in 1868 when he was 15, an argument over a wrestling match, at which point he was obliged to become a fugitive. And Hardin , very much like Jesse James and many of the earliest gunfighters, was a diehard rebel who felt like the South was being unjustly occupied and dominated by Northern troops. And so Hardin embarked on a career for six years where he kind of wandered Texas killing people. And generally not for reasons he expected, almost always because of arguments and things that went round. Hardin was the type of guy, if you said something wrong about Texas, he would shoot you. I mean, he was literally a serial killer, and he was almost certainly, by the dictionary definition, a psychopath.

He also embodies this spread of Texas violence because after killing, and he is credited between 24 and 42 killings. By the time he was 21, most before he was 18. And of course, his most famous jaunt was the single cattle drive he took up the Chisholm Trail to Abilene in 1871, where he came face to face but did not shoot while Bill Hickok, who silkily kind of disarmed him before gunplay. But in the four months that Hardin was in the Abilene area, I think I tied it up that he killed, believably, eight men, five at once in a big gunfight out on the prairie with his cousins. And the most famous of Hardin ‘s gunfights, which really was not a gunfight, was the one where supposedly it was always said that he killed a man for snoring. And of course, for 150 years, people have kind of rolled their eyes and said, oh, that’s just a Texas myth. But the facts are he was asleep or drunk in his hotel room there in Abilene at four in the morning, and he shot a man in the next room through the wall with four gunshots. And they probably didn’t get into an argument since they were in separate rooms and couldn’t see each other.

I think, why else would you shoot somebody through a hotel room wall than if they were snoring? So I’m prepared to believe it.

Brett McKay: Who was the most overrated gunfighter?

Bryan Burrough: Johnny Ringo. He was very famous up until, let’s say, the last 50 years. Like, there were Johnny Ringo television series in the ’50s. There were Johnny Ringo movies during the ’60s. He was kind of a second-tier gunman in Tombstone, best known as a gunfighter who had a particular animosity for Doc Holliday. But beginning in the ’70s, a series of researchers basically realized that not only was he not a gunfighter, he had never been in a gunfight of any type. The only time we ever understand that he actually fired a gun in anything like Anger was once in a drunken argument with a miner in which I think the miner was winged. And the only other gunfight he was ever in, he was probably the one that killed him. In fact, we believe he committed suicide, found dead against a tree in the middle of nowhere. Wyatt Earp, famously years later, decades later, bragged that he did it, but he didn’t. And we now know that Johnny Ringo, and none of this was Johnny Ringo’s fault, the Old West kind of disappeared from American conscience for about 30 years, from the 1890s into the 1920s, when it was rediscovered, famously by a magazine article in which the writer’s lead was, who remembers Billy the Kid, which ignited this interest in gunfighters and all manner of Western things.

And that was really the beginning and in some ways the peak of Ringo’s fame. I mean, there were people that wrote in books that he was not only the greatest of American gunfighters, but that he was a college man known for spouting stories in Latin, all of which is purely made up by modern writers or writers from the 1920s. Poor Johnny Ringo was not responsible for any of it. The runner up though was probably Wild Bill Hickok, who, while he became a gunfighter of note, when he first got all the attention as a result of that opening gunfight there in Springfield, Missouri in 1869, the writer wrote with a straight face in Harper’s Weekly, you know, a notable magazine that he had no doubt that Hickok had killed over 100 white men. And by my count, the exact number at that point would appear to be two, although two men that he wounded in one of them died, but they were killed by other people, so technicality. But even that is a long way from 100. So that type of thing, you know, you see in three or four of these careers.

On the other hand, Brett, there’s any number of gunfighters whose stories are even better than we remember. You know, Hardin is probably underappreciated solely as a source of, you know, gunfighter mayhem.

Brett McKay: This is probably a morbid question, but after all your research, which gunfight was the most impressive, for lack of a better word?

Bryan Burrough: Well, you know, I mean, I hate to go to the one everybody knows, but O.K. Corral is amazing. Eight men, which was initially 10, and several of them backed away. And so it was four Earps versus three bad guys. So seven guys shooting from ranges from five to 15 feet. And a gunfight that lasts 30 seconds. Three guys end up getting killed. That was pretty impressed. The other two crazy ones were one from California, of all places, during the gold rush, before the actual gunfighter era, but in kind of a manic prelude, in which one guy on a mountain trail with his sack of gold powder was ambushed by a bunch of bandits. And he killed 11 of them by himself with a gun and then with a knife. But hands down, the craziest gunfight of all, I think, and I got to give you the short version of this because the long is too great, was a group, a young Hispanic deputy in New Mexico in 1884, in what’s today the town of Reserve, way out on the Arizona border up at altitude, had the temerity to arrest a drunken Texan for shooting his gun in the air.

The next morning, after he processed him through the courthouse, he came out and there was a crowd of 80, eight zero Texas cowboys who worked at the ranches outside town, who chased him down. He took refuge in an adobe hut and they kept him under gunfire under siege for the next 36 hours. He ended up killing four of them. He walked out unhurt in part because everyone only learned afterwards that this little adobe hut had a false bottom and he was able to lay flat about 18 inch below ground level. And these cowboys just kept shooting and shooting and shooting and every single shot went over his head. And the young man’s name was El Fago Baca and he went on to be tried and found innocent twice of murder and went on to a long career in New Mexico as a politician and a sheriff of note.

Brett McKay: So we’ve talked about the gunfighter era. When did it start drawing to a close?

Bryan Burrough: You know, after the early 1880s, that’s pretty much the peak of the gunfighter era. You certainly see gun violence for another 20 years, but a lot of the craziest stuff from the early days begins to pass and gunfights in the 1880s and 1890s tend to be much more about something, typically about fights over the division of resources, whether it’s cattlemen, you know, fighting farmers or fighting sheep farmers. It more often becomes about something in those later years.

Brett McKay: It’s not about honor anymore.

Bryan Burrough: Not as much. I mean, you can certainly find gunfights that seem to be taking part for a man’s honor, but what you see much more often is, you know, big feuds over land. And, you know, after 1901, there were certainly gunfights. I can name some, but what you find there is that in terms of newsworthiness and cultural importance, frontier violence kind of gives way to a fascination with frontier entertainment. So Western movies first, but also Western literature. I’m thinking of the Virginia Owen Wester’s 1901 book, certainly the rise of Remington and his sculpture. So I argue that it’s in that decade, in those years, in the early part of the 20th century, where Western violence begins to move from headlines to history. And so I think that’s a fair place to end the story.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And then, as you said, the gunfighter kind of got forgotten a little bit, but then there was this revival in the ’20s. And it just seemed like for the next 30 years, through the 1950s, I mean, it just provided fodder for Hollywood for these stories where they’re pumping out TV shows, radio shows, comic books, movies. What do you think was going on there? Like, why this sudden uptick in the interest in the Old West and particularly the gunfighter?

Bryan Burrough: Well, it’s funny because the gunfighter really wasn’t a thing in the Old West. I mean, you could read stories about gunfighters, but in terms of like dime novels and popular entertainment, Indian fighters, even detectives, soldiers were much more popular stock figures than gunfighters.

Brett McKay: Yeah, like Kit Carson was a popular dime novel character.

Bryan Burrough: Much bigger deal than Hickok. You know, Billy the Kid became a household name, but he was the rare gunfighter that at the time achieved true national fame. And much of that was just because he had a stellar nickname. But it really wasn’t until the 1920s that the gunfighter was introduced in a serious way into American entertainment. But what took it to the next level was the introduction of television around 1950, which suddenly out of nowhere had, you know, three or four networks and a real need for what we call today original content for original programming. And frankly, a gunfighter show was stunningly cheap to make. You just needed a back lot with some Old West buildings. And then it’s what, you know, 10 white guys and some guns. I mean, this is not expensive television to be made. And something like a third or 40% of every TV show on in during the ’50s, during the first 10 years of modern television, was a Western and most of those featured a gunfighter. But, you know, what really got good though, for those of us who are aficionados, was in the late ’60s and early ’70s with the introduction of Butch Casting the Sundance Kid in ’69, it really introduced something like more realistic Westerns to Hollywood cinema.

If you look at the Westerns that came out from Hollywood from ’69 for the next decade, I’m thinking about the, you know, Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch, McCabe and Mrs. Miller with, wasn’t that Warren Beatty? I mean, suddenly, you know, we lost kind of the glamour and the glitz and the, you know, singing to damsels in the moonlight and got something that was gritty and dirty and nasty and bloody. And those are the movies I think that have fueled, to the extent that gunfighters have continued to be a thing, I think much of it was because of those movies more even than 50s era television. Having said all that, and with apologies to Taylor Sheridan and Yellowstone and all that, you know, the gunfighter is just not what it used to be. A lot of the adventures, a lot of the narratives that used to star gunfighters now are set not in the Old West, but in outer space. And, you know, it’s a shame. There’s still a Hickok or a Billy the Kid movie every five or 10 years, and sadly, they no longer really attract the best and brightest. A lot of them just go kind of what we used to call straight to video.

Brett McKay: What do you think is the best movie that depicts an Old West gunfight?

Bryan Burrough: Ooh, you’re killing me here. There’s so many. I mean, I like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid a lot. It’s closer to reality than a lot of people want to believe. The Wild Bunch has to stand out because it was not only the most violent, but people forget it was the first most violent, you know, it was the first over the top violent Western. I think today, you know, just thinking about movies made in the last 40 years, it’s hard not to nod toward the Kurt Russell Tombstone from 93, which people just seem to love. And with the passing of Val Kilmer earlier this year has kind of been rediscovered for a lot of people. I watched that again the other day. And some of the performances in that movie from Powers Booth as Curly Bill Brocious to Michael Biehn as Johnny Ringo are just really wonderful. But even though Val Kilmer, of course, steals it, are just really wonderful. And yesterday I just watched the movie that it went up against, which was the Kevin Costner Wyatt Earp movie, which put me to sleep then and pretty much put me to sleep again the other day.

How do you make a boring Wyatt Earp movie? Well, they pretty much did.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I remember when I saw Wyatt Earp when it first came out in the movie, I fell asleep in the movie theater.

Bryan Burrough: There you go.

Brett McKay: One movie, and I remember you mentioned it, and it’s not very good. But I remember when I watched this when I was, I don’t know why I was watching this rated R, I was like 9 or 10. But back then my dad didn’t care. He was like, well, you know, he just watched HBO. And if you decide to watch with him, he’d just let you watch rated R movie. Young Guns, I for some reason, I watched that movie and I became fascinated with Billy the Kid after I watched Young Guns, but it’s pretty cheesy.

Bryan Burrough: You know, but it’s not cartoonish. Yeah, the facts don’t really jive. I mean, it’s what the best thing you could say about it is it’s two or three cuts above Young Guns 2. And the one thing that I appreciate about it, watching it is that Emilio Estevez’s portrayal of Billy is someone who’s not totally stable. And that is the sense that you get about Billy, that he was not entirely stable. And I thought more than a lot of Billy the Kid movies, he brought that out.

Brett McKay: Well, Brian, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Bryan Burrough: Oh, golly, you know, this is my eighth book. It’s called The Gunfighters. It’s available on Amazon and in pretty much all bookstores now. It’s the first one I’ve written about the Old West. It’s the third I’ve written about Texas. I wrote it for people who don’t know much about the Old West, but were looking for one book that would kind of not only introduce them to a lot of these characters, but would really fill in in footnotes and elsewhere with other books where you can go to read, you know, if you want the best books about Billy the Kid, the best books about Wyatt Earp and such. You know, I made a point to point to other people’s work here, too.

Brett McKay: That is it. Well, Brian Burrow, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Bryan Burrough: Brett, fabulous. Thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Bryan Burrough. He’s the author of the book, The Gunfighters: How Texas Made the West Wild. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check out our show notes at aom.is/gunfighters, where you find links to resources where you delve deeper into this topic. Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you find our podcast archives and make sure to sign up for our new sub stack newsletter. It’s called Dying Breed. You can sign up at dyingbreed.net. It’s a great way to support the show directly. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, it’s Brett McKay. Remind you to listen to the AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.