Welcome back to another episode of the Art of Manliness podcast!

In this edition, we talk to author Marcus Brotherton about his new book, co-authored with Adam Makos: Voices of the Pacific: Untold Stories of the Marine Heroes of WWII. Marcus has written over 25 books, including New York Times bestseller We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers. In addition to writing books, Marcus regularly writes at his blog, Men Who Lead Well, as well as at The Art of Manliness.

Highlights from today’s show:

- The three factors that made the battles in the Pacific some of the most atrocious of WWII.

- The average age of Marines fighting in the Pacific.

- Lessons that today’s man can take from the men who fought in the Pacific.

- Much more!

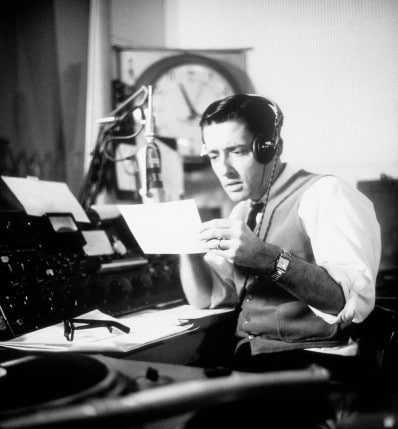

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Well, our guest today is a regular contributor to the Art of Manliness. It is Marcus Brotherton. Marcus is an author and has written over 25 books and he has focused a lot of his writing on the history of the World War II. More specifically, the lives of the men who fought in World War II. One of his books actually reached the New York bestselling list. It’s we who are alive and remained untold stories from the Band of Brothers and today we’re going to talk about Marcus’s new book Voices of the Pacific: Untold Stories from the Marine Heroes of World War II. Alright Marcus well, welcome to the show.

Marcus Brotherton: Thanks, Brett.

Brett McKay: It’s actually interesting. You are actually my very first podcast interview, when I started the podcast with the Band of Brothers book. So let’s talk about Voices from the Pacific.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about, what I found really interesting is this you teamed up with an author and you’re a different writer on this, Adam Makos, who had that great book…

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. His first book Higher Calling did very, very well.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So, how did that partnership come about?

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. I met Adam a number of years ago at an air show and worked with him on several editing projects over the years. He is a very smart guy, very driven. He has got a huge heart of compassion for the men for telling their stories and so when it came to this project Voices of the Pacific, unlike The Men of Easy Company Association, it was much more difficult to track down the Marines who are featured in the Pacific. There just was one main association for them. So, Adams’s company had spent two years doing this, meeting the man, explaining the project, winning their trust and then the time came to do a history project, Adam called me up and said, hey, you know, you’ve done this before with We Who Are Alive and Remain, time is of the essence with these men and their ages, thus join resources, do it together. You know, it’s perfectly a good partnership all the way through.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. That actually, you just mentioned something that leads me to my next question. Is the reason why, it just seems like there is the perception is out there that the men who fought the Pacific don’t get as much attention as the men who fought in Europe like the Band of Brothers, is a reason of that because they’re so hard to track down, is that part of the reason why there hasn’t been much attention brought to these men?

Marcus Brotherton: Undoubtedly, you know I think the – well, I think the spotlight is probably increasing over the years certainly battles like Guadalcanal and Okinawa where they received good coverage. You know Clint Eastwood produced two movies, Flags of Our Fathers and Iwa Jima. So, it’s a more Grassley side of the world, let’s say. I mean, certainly there were atrocities in the European Campaigns, but the battles of the Pacific by enlarge I would say you need a stronger stomach to take them. So that may be just keeps, keeps more people away.

Brett McKay: What are some of the differences I mean why, why were the battles more atrocious in the Pacific than say in Europe.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. I could think at least three reasons. One was just the climate was certainly different, I mean the battle about stone in Europe, it was all about snow and cold and not having enough more clothes. The battle for say Pelileu was all about heat. You got a 120 degrees days, then men are all thirsty, there is not enough water in our canteens, there is flies everywhere and then it’s such a different enemy. I mean Imperial Japan was a pretty modern society in many ways. You have this emperor Hirohito, who is the, he is a political head of the state of Japan during World War II and then he is also kind of considered sacred. So, he is believed to be directly descended from a sun god. I think it was, so he is considered divinity and that creates a climate where a lot of Japanese soldiers during World War II, they are really fanatical in their devotion to him. They are willing to die in his honor rather than be captured by the enemy and so, you really have that different world view, you know and in Germany, you have at least a – at least a semblance of a Judeo-Christian world view among the soldiers any way. They recognize such things as Mercy, tolerance and compassion, basically what the Western world considers fair play. By contrast in Japan, you have a world view that considers Mercy, tolerance and compassion to be signs of weakness. So, in Japan if your enemy surrenders to you, you wouldn’t treat them with Mercy, you would treat them with contempt. Surrender in the eyes of the Imperial Japanese soldiers, a sign of weakness, cowardice. So, the Japanese soldier even, even if he is being beaten, he will not surrender. He is going die by suicide first, and this creates a very brutal enemy, a very aggressive enemy. It is the enemy who doesn’t fight by the same rules that are understood by the western world.

Brett McKay: I imagine that was a big culture shock for a lot of these young men who were used to that notion of fair play and they come to an enemy who has no regard for that whatsoever.

Marcus Brotherton: Absolutely, absolutely.

Brett McKay: And yeah, talking about the climate and the weather that was something that really jumped out to me while I was reading the book. The thing that really stuck out to me was the emphasis on the Jungle Rot. Lot of those, lot of the men brought up this fighting Jungle Rot. Can you kind of describe what Jungle Rot was?

Marcus Brotherton: A Jungle Rot, a horrible condition, you might call it jock itch today, but it would be like a 100 times worse and it would be in various of your body than you could imagine. So, it comes from the situation where you’re just always wet all the time and coupled with the wet, you’re always in this really hot humid climate.

Brett McKay: And it seems like a lot of these men too got malaria and they had it for 30 to 40 years after the war. They are battling this.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah malaria, very tricky and sneaky degrees disease where you know it can sort of hiding your spleen, I believe it is and like you are saying, where you can be fighting it for years and years to come, so very, very tough situation there.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And another aspect of the environment that I found was you know different from say what the Band of Brothers face was these islands and we think of islands in the Pacific, I think there is sort of idealize version of islands in the Pacific comes to mind like you know sandy beaches, pristine waters, but the islands that these men were fighting on were, some were just made of coral like it wasn’t made of sand, some were made of just volcanic ash and then some were just dense jungle. So, these weren’t like typical islands I guess.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. Pretty difficult fighting conditions all around and you think about how many times a soldier may be down his knees or on his belly and you know crawling along you know to keep out of sight of gun fire and if you’re falling down on coral you know 10 times within an hour I mean that’s going to really rip up your front pretty easily, pretty quickly, so it’s just brutal condition these guys are fighting in.

Brett McKay: Yeah and even digging foxholes was impossible, like they could.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah just kind of get like a shallow hole on that was their foxhole. One thing that struck out to me, as I was reading this book was the age of these the men who fought in Pacific. I mean we’re talking 16, 17 years old with some of them, was that something common in the marines during World War II?

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. You have a great question. It may have been just the men we featured in this book. You know, young enlistments were fairly similar across the board. I think they had actually be 18 to go in, but a lot of men just, it’s not like you had really concrete documents back then and in many ways, so you know I think one of the factors that really sets apart the studies of the Pacific is length of time that the men fought for. You know, in Band of Brothers, you have a much long training period to begin with and essentially, the men they fight for about a year from D-day June 1944 to probably May 1945 in Austria where the high points mainly began to be rotate at home. So, the marines featured in the Pacific by contrast they’re fighting from say like August 1942, which is Guadalcanal until August 1945, VJ day and then even some of them until 1946 they are fighting into occupied China. So, it’s more like three years of battle there just a longer series of campaigns on that side of the world.

Brett McKay: And, I also found it interesting how a lot of these men ended up in the marines and a lot of times, it was just sort of happens to answer, they ended up in the marine, like they try to get into the navy, but the navy rejected them, they try to get in the army, but the army rejected them and then they showed up that the marine recruiting office and they are like, okay I will take you. It wasn’t like the Marines were their first choice in a lot of cases.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah like Sid Phillips I believe it was. It was just a shortest line and he had to get back to work or school or something like that. It’s like well you know you can either wait for hour in this line or we can wait for 5 minutes in the line for marine. So, that’s how it became a marine.

Brett McKay: It’s amazing though I get to that, the way you make that choice could have such life altering you know, life-altering impact on you.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: It could have been a Band of Brother, but because he – it’s a shorter line. I’m going to go serve in the pacific now.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah.

Brett McKay: So, let’s talk about the men today. What’s the average age of the veterans who have survived?

Marcus Brotherton: Most of them we talk to are late 80’s, early 90’s. One of the men is 95. Yeah they’re all the time is ticking like we say.

Brett McKay: Yeah and how many of them are left?

Marcus Brotherton: I couldn’t speak for the marines on the first division, I was told the main features in our book I think it’s all except one or two now you know.

Brett McKay: Wow, that’s amazing. Marcus, is there anything I mean you’ve been studying or talking to World War II veterans for several years now, but is there are any way that you’ve changed as a man after talking to these specific men who served in the Pacific.

Marcus Brotherton: Well, I am continually astounded and continually challenged really about the men I meet in these projects. A few years back, I was in an airshow, I met TI Miller who was featured in the book and you know after the war TI he comes home and right away marries a childhood sweetheart and he finds the only job that he can find in West Virginia where a young man can get without education and that’s mining coal. So, you know, he goes to work right away in the coal mines pretty tough think you are 22, 23 and you’re mining coal day long. So, one of his is first jobs is called cleaning belt and it’s a dusty heavy job. He is down in the barrels of the mine just every day in darkness just watching that belt go by basically and like you’re talking about malaria, TI had contacted malaria back in the Pacific and one of those things that when you it battle the rest of your life, it just sort of shows up without warning anytime and anywhere and symptomatically, its fevers and chills and aches so bad, you think your body is going to, going to rattle apart, TI said. So, one day TI Miller is down in the coal mine, he is cleaning belt and he feels this malarial fever coming on very quickly, very suddenly and he is almost instantly in this deliria and he is beginning to hallucinate and you know if you or I are already are beginning to hallucinate, you know, we might see some scary things or some normal things, but TI goes back in his mind and he begins to hallucinate about all the horse he has faced during the war. So, he starts literally seeing these dead Japanese soldiers riding by on a belt in front of him, you know, basically his phantoms are in front of them and he is still with it enough to know that he needs to get it serviced pretty quickly. So, he calls up another miner and the other miner helps him get to the surface and up to the side and his apparitions basically disappear once he gets to the surface. So, he goes in the hospital, he spends another 20 days in the VA Hospital recovering from his fever. The point of that story is, a story like that, I meet a man like that. He tells me that story face-to-face and I just go wow, you know, that helps me put my own job into perspective. You know, we all have bad days at work, even though you know some of us have really great jobs, but the point is we’re down in the darkness of the coal mine fighting off malarial attacks while having hallucinations of dead Japanese soldiers and so, a fought like that goes just a long way toward me being grateful today.

Brett McKay: Yeah. That’s an amazing story. Is there any, is there another story from the interviews you took part and that really stuck out to you?

Marcus Brotherton: One of the saddest story I think Jim Young, he tells this, it’s a pretty tragic narrative really, one day the navy is helping supply the marines on Guadalcanal, I believe that it is and so Jim Young, he has come down with his bad case of hemorrhoids, which he kind of set with a chuckle when he told me about it and so the lieutenant calls him over, gives him a sword and says, hey, you know, take 12 men, you’re squad leader, whatever you know, go down to beach, help unload this destroyer and he is like man, I can hardly walk much less help unload a ship. So, lieutenant comes and calls over the Carmen, Carmen check out, say oh yeah, you know this is poor Jim, you know, he can barely walk and so the lieutenant, he calls another man to take Jimmy Young’s place. That other man’s name is Clifton Barger he is a Corporal. So, Clifton Barger and the man they go down to the beach, they begin to unload the ship and just sort of a typical afternoon on Guadalcanal, air raids start and enemy planes fly over and bombs start falling down on the men. So, the men they all jump in the trucks and try to make a run for it. It’s too late, bombs are raining down and they all jump in this bomb crater and I think they’re going to be safe all together, but it pretty much proves to be a direct hit and one of the bombs falls right on top of them. So, one of the marines survives the blast when he runs back to the company with the news, the Lieutenant and Jimmy and other guys they jump into a jeep, they race to the spot and they say that when they get their it’s just a, just a blood bath, you know, five of the guys are dead, everybody is badly wounded. You could hardly tell who is who and Jim Young finally locates Corporal Barger, the guy who has taken this place and barter is badly wounded. He just begging for water and Jimmy Young said a fragment about the size of the softball had gone through this guy and so they really, there isn’t anything more than they do for Corporal Barger and churn off. There is a few last words spoken and then, Corporal Barger dies. So, Jim Young is telling me the story, I mean, it’s 67 some years later and tough as nails Marines and his voice is choking, his voice is cracking when he is telling me the story and he says you know it was my fault that this man was killed instead of me. It was supposed to my working party, but he died so that I could live. So, you know a story like that. I’m just hanging on just listening to it and so much power, so much poignancy and so much selflessness coming through. This whole theme of another man dies, so that you can live and Jim Young says how are you going to live out the rest of the days in light of that fact. That’s just a powerful statement.

Brett McKay: Wow. It is a really powerful. Let’s talk a little bit about, you know about a Jim Young a little bit. Did he talk about how he dealt with that grief or that feeling of responsibility when he came home to civilian life?

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah you know it’s a story that’s strangely enough is not isolated to him. I mean it’s basically what happened in Saving Private Ryan and I think a man lives with a sense of obligation and a sense of uncommon gratitude and he wants to live his life dedicated to somebody in terms of what was given to him.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And what I loved about the book too is that you don’t’ stop with the story when the war is over. You follow up with them and see you ask them about their life after the war and what I found interesting with this book and also with your interviews with the men who have served with the Band of Brothers. It seems that for the most part men who served during World War II, they had their wounds, they had their emotional scars, but for the most of the it they seemed well adjusted. They got back into civilian life. They had jobs and I guess maybe, maybe it’s just my perception, perhaps it’s wrong, but then you didn’t see a lot of the posttraumatic stress syndrome, that you see in a lot of are we turning veterans today in our most recent wars. Is that perception correct, I mean, was the lot of guys who served in world war II, a lot of men come back and get back in the civilian life okay or did they actually have those scars?

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah. It’s a good question, may it simply be the perspective of the time that we’re dealing with here in the books. I am not part of the veterans of World War II adjusted any better, maybe it’s just a perception like I say, sometimes they just didn’t talk about it, you know, back in that generation, it just a man came home and a lot of the men talk just say, well you know nobody wanted to hear what I had to say, so I just climbed up for rest of my life and until I was elderly or whatever. There certainly were a lot of stories, you know, maintain home, dealing with nightmares, flashbacks, rage, depression, men of that generation turned to alcohol, a lot of the time it’s kind of that generation’s drug of choice and so I had seen more of the veterans have talked to would say that war effects any man, you know, no matter what time period he lives in, so it’s really raising a valid question here and I don’t all the specific answers to it, it’s you know, can we do anything differently or battle as a country in a culture to help our returning soldiers, really that’s the question.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Marcus Brotherton: And

Brett McKay: Go ahead. Well, it seemed to me that in your interviews a lot of these men had communities, like tightknit communities to return home to and.

Marcus Brotherton: Tighter than today maybe yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah and I think you know we have that less so day. A lot of people, they come home and you have these soldiers they are sitting in their apartment by themselves, away from family, no friends, and I guess two of us, one thing I found very interesting about soldiers who fought in World War II, they have the reunions right where they get back together and I don’t know is that something that’s common with more recent veterans. Do they have reunions or is it too soon for that?

Marcus Brotherton: I honestly don’t know I mean I hear about them in the news once in a while. Donovan Campbell wrote that great book. It was Joker One where he really talks about the commemoratory that has men felt and he really led with that, really a theme of love is the word he uses, which is the kind of the word that you don’t expect, you know, veterans really to use, but that was really, the kind of the guiding and shepherding principle that he had with those men, so it’s a good question I mean you don’t have, how do we help veterans of today transition back to our communities, to our workplaces, to our training programs, or universities or churches, it’s a great question and you know certainly begins with a gratitude. I think we do see that much more today than we did you know so say in the Vietnam era and yet gratitude can’t exist on an isolated plane. Gratitude is got to be expressed with actions followed up with actions. You know, it begins by saying thanks for what he did and then followed up with me and so, you know, great question.

Brett McKay: One of the things that I love what you do with your writing on your blog and you’ve done it on when you written articles for the Art of Manliness is extracting lessons that men today can apply to their life from these soldiers who fought in World War II. What are some of the lessons that you think that men can take today can take from the men who fought in the Pacific.

Marcus Brotherton: Yeah, I always want to let the men speak for themselves as much as possible and so most of the lessons that I do talk about or the lessons that they’ve actually, they’ve actually talked about and the things that they wanted to convey to the men, so I guess I want to be careful to answer that question like I don’t want to stand in place with the man and yet it is really hard as a journalist to not interact with this material and have that effect you as a man or have it you now life lessons are often universal in terms of humanity, so you think about you know big lessons of war and I think we see a lot of iconic images today both from wars of yesteryear and wars of today, and I think iconic images of national triumph are really a good thing, you know, you can think about the 82nd division marching in New York Times or in New York ticker tape parade or you think of the image of the nurse who has kissed sailor in Times Square after Japan surrendered and those images are really good, really good and yet it’s the other images of the war that we also need to continually bring to national forefront. It’s the blood images, the gruelish images, it’s you know its Dan Lawler. He has addressed that story in the book. He finds this five-year-old girl in Okinawa and she wraps her tiny arms around his neck and he just waves at the injustice of the civilians being caught in crossfire. I mean, that’s an image we want to burn into the consciousness today for, you know, Clarence Ray. There is a scene in the book where he goes to this hospital in Guam after he is wounded in his arm and Clarence Ray, he glances around the hospital ward and just you can kind of tick him off, one by one. There is a man with both legs amputated. There is another man with his jaw shot off. There is another man who is burnt so badly. He doesn’t look human anymore and that’s really the message of this book. Its wars, war and we can never forget that.

Brett McKay: Very powerful stuff. So Marcus, you’ve interviewed, you’ve talked to men and interviewed men who fought in Europe, you’ve talked to men and interviewed men who fought in the pacific, whose story do you plan on capturing next?

Marcus Brotherton: Well it’s always a great question and I’m always on the lookout for the next great story, you know, strangely enough, I’ve been doing a lot of, I run an editorial company in my off days I suppose, not in my off days, but on my other time and I’ve been doing a lot of editing work lately with historical fiction, which really fascinates me, so I just had a project by a guy name Shawn Hoffman. He is a movie producer in Hollywood and he wrote a historically based novel called Samson, it’s about Boxers in Oshawa’s and so Shawn, he uncovered this fact that, Nancy Guard, they used to hold boxing matches on weekends for entertainment and basically they would get two Jewish prisoners to fight and the winners would receive extra food ration and a loser would go to the gas chambers. So, I think that book is going to out maybe late this summer. So, it’s just projects like that I’m always on the lookout just the next, next powerful story.

Brett McKay: Very great stuff. Well, Marcus, thank you so much for your time. Voice of the Pacific was a great book and I can’t wait to – I hope my readers go out there and check it out.

Marcus Brotherton: Well, thanks Brett, it’s always great to talk.

Brett McKay: Our guest today was Marcus Brotherton; Marcus is the author of the book, Voices of the Pacific: Untold Stories of the Marine Heroes of World War II. You can find at book on amazon.com or any other book store and you could find out more about Marcus’s work at marcusbrotherton.com.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com and until next time stay manly.