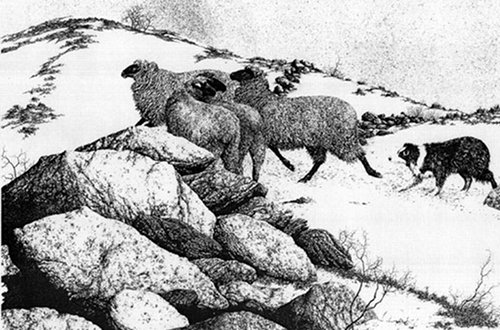

Over the past two weeks, we’ve been taking a look at the sheep/sheepdog/wolf paradigm as set out by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman. In our first post, we introduced the analogy and these different roles: Wolves are the bad guys of the world, the evil sociopaths who seek to harm and exploit others. Sheepdogs are the guardians and protectors of society — those that aren’t afraid to stand up for right, even when it means going against the crowd, and have the courage to face danger and save others. The rest of us lie somewhere on the sheep-sheepdog continuum, with the vast majority of the population firmly on the sheep side. In our last post we explained the sociological and psychological reasons for this.

Now for today’s post, I had naively planned on laying out all the specifics for the physical and mental training a man would need in order to transform himself into more of a sheepdog than a sheep. But as I often do with series (remember when I thought our 7-part honor series would only take 3 articles?! Harharhar), once I dove into my research and investigation, I learned that there’s much more to cover than I originally thought. So rather than delving into the nitty gritty at this point, the goal with this post is to lay out some broad principles on what a man needs to do if he wants to become a sheepdog. The focus is on what Grossman calls the “software” or mindset in sheepdog training. Many of the points below warrant their own articles, and that is exactly what they will become over the next year. Hopefully, what this post will provide is a framework for these future posts and offer you a roadmap on your own journey to becoming a sheepdog. Also use the post as a resource page and jumping off point for doing your own research; we’ve linked to quite a few articles that ourselves and others have done over the years in regards to these topics.

Decide to Become a Sheepdog

Unlike the real-life sheep or sheepdogs which are born into their animal roles, humans default into passivity unless they make the choice to become proactive protectors. Grossman emphasizes the weight of this decision in his book, On Killing:

“In nature the sheep, real sheep, are born as sheep. Sheepdogs are born that way, and so are wolves. They didn’t have a choice. But you are not a critter. As a human being, you can be whatever you want to be. It is a conscious, moral decision.

If you want to be a sheep, then you can be a sheep and that is okay, but you must understand the price you pay. When the wolf comes, you and your loved ones are going to die if there is not a sheepdog there to protect you. If you want to be a wolf, you can be one, but the sheepdogs are going to hunt you down and you will never have rest, safety, trust or love. But if you want to be a sheepdog and walk the warrior’s path, then you must make a conscious and moral decision every day to dedicate, equip and prepare yourself to thrive in that toxic, corrosive moment when the wolf comes knocking at the door.”

So the first step in becoming a sheepdog is to simply decide to become one. Don’t take this decision lightly. There are heavy moral, physical, emotional, and psychological costs that come with it. When you decide to become a sheepdog, you’re also deciding to live a life of service to your fellow man, to run to danger when others flee, and to stand up for right despite the cost. Are you ready to accept those responsibilities and risks, and the consequences that come with them?

Adopt “If Not Me, Then Who?” as Your Mantra

As we discussed in our previous post about our natural sheepishness, all of us are prone to the Bystander Effect. Whenever we’re part of a group, our inclination to help or take action when we see a threat or a need diminishes. You think that someone else in the group will do something, so you hold back. The problem is, that’s exactly what everyone else in the group is thinking too. While everyone is waiting for someone else to do something, no one does anything.

To overcome the Bystander Effect, adopt “If not me, then who?” as your personal mantra. Decide today that you will take action whenever you see something that is wrong. Stop thinking that someone else will come along and do it. Chances are they won’t. If you don’t do something, nobody will.

One example of a man who overcame the Bystander Effect by living “If not me, then who?” was an 18-year-old busboy named Walter Bailey. Because of Walter’s decisive action, he saved hundreds of lives in one of the most fatal fires in U.S. history. Back in 1977, Walter was working at the Beverly Hills Supper Club, a popular nightclub and theatre just outside of Cincinnati. Around 8:30PM on May 28, a fire ignited in one of the club’s rooms due to faulty wiring. Two waitresses walked into the room, noticed the fire, and went to alert their supervisors. Fire trucks were dispatched to the club, but no efforts were made to evacuate patrons. At the time the fire started, nearly 3,000 people were in the building, including members of a large wedding reception. Because the building lacked adequate firewalls, the blaze began to quickly spread to other parts of the club.

When the fire started, Bailey was working in another room, clearing dishes as over a thousand people listened to a comedic act. A waitress told him about the fire and he immediately went to let his supervisor know and recommend that he clear the room. His supervisor just gave him the brush, so Bailey went to find the club’s owners. But then he turned around. “This is stupid,” he told himself. “I’m wasting time. Either he has to clear this room or I will.” He told his supervisor again to begin the evacuation, but the supervisor shrugged and walked away. Instead of waiting for someone else to do something, Walter Bailey took matters into his own hands.

“This isn’t going to do,” he told himself. “This room has to be cleared out, and it has to be cleared out soon. I’m probably going to lose my job, but I’m just going to do it.”

Bailey boldly walked up the steps of the stage and grabbed a microphone right from the hands of a comedian in the middle of a bit. An awkward silence fell over the crowd. “I want everyone to look to my right,” he said. “There is an exit in the right corner of the room. And look to my left. There’s an exit on the left. And now look to the back. There’s an exit in the back. I want everyone to leave the room calmly. There’s a fire at the front of the building.” Then he left to warn other customers in other parts of the club.

Some of the people who heard Bailey’s warning began to leave, but many just stayed put (Normalcy Bias!).

The fire soon consumed the entire building. Two hundred people were injured and 165 people died that night, making the Beverly Hills Supper Club the third deadliest fire in U.S. history. But thanks to one young man who overcame the Bystander Effect by asking “If not me, then who?” hundreds of people survived.

Adopt “Not if, but When” as Another Mantra

“Instead of saying, ‘If it happens then I will take action,’ the warrior says, ‘When it happens then I will be ready.’” – Grossman, On Combat

I first learned this next mantra from AoM contributor and survival instructor, Creek Stewart. It’s how he ends all his emails and blog posts. As I researched for this series, I learned that not only is it a popular phrase among preppers, but also “professional” sheepdogs like soldiers, police officers, and firefighters.

“Not if, but when,” is a reminder not to live in denial of the fact that bad things can and will happen to you and those around you – that it’s not a matter of if, but when they happen.

In truth, you might very well go your whole life without getting in a violent altercation, being faced with an emergency situation, or grappling with a weighty ethical dilemma; the mantra describes a mindset rather than a statistical truth. But most folks seize on those chances and swing their mindset in the opposite direction — pretending that bad stuff will definitely never happen to them. While they recognize that evil exists or that natural disasters occur, they try to, as world-renowned security expert Gavin de Becker puts it, “compartmentalize the hazards in order to exclude themselves.” They tell themselves things like, “Sure, violence is a problem, but that doesn’t happen in this part of the city.” “Well, yeah tornadoes kill people every year, but we don’t have to worry about that here.”

Besides giving people a false sense of security, denial gives people a false sense of sophistication. People don’t want to seem overly paranoid about unseen dangers – it makes them feel cool and smart and above it all to wave off the need for such preparations. To them it doesn’t seem rational to train for things that might not happen, and figure that if by wild chance they do happen, they’ll just figure things out then, or that the government or aid organizations will see them through it anyway.

But to me, training to be a sheepdog is very rational. Here’s my own thought process on it: 1) even if my skills aren’t called upon in a crisis, learning those skills is enjoyable, offers a sense of confidence and mastery, and makes me a more complete and knowledgeable man, 2) even if my training isn’t called upon for a big crisis, those skills, along with my sense of confidence, will be very effective in solving smaller problems, 3) training for a variety of scenarios doesn’t necessitate paranoia, just awareness, and 4) if something does happen, I am completely ready, and don’t have to live with the “if only” regret: “If only I had a bug out bag!” “If only I took the handgun training!” “If only I took action!”

To me, there’s no downside, and it’s a very rational calculation. There is a time investment, of course, but I think all men would be better served carving out some time from our abstract cyber surfing to learn some tangible, hands-on skills. It feels good to have them, very good indeed.

I think in the end people don’t like to think of themselves as vulnerable, and to soothe the cognitive dissonance they feel when they do, they wave off training for those scenarios as paranoid or stupid. The discomfort is gone and they feel great about themselves. But they have no bulwark against a crisis besides this feeling of complacency.

Grossman says the thing that separates sheep from sheepdogs is denial. “The sheep pretend the wolf will never visit, but the sheepdog lives for that day.” When you live your life as if danger and evil will never come knocking at your door, you might as well open your mouth and say “Baaa.”

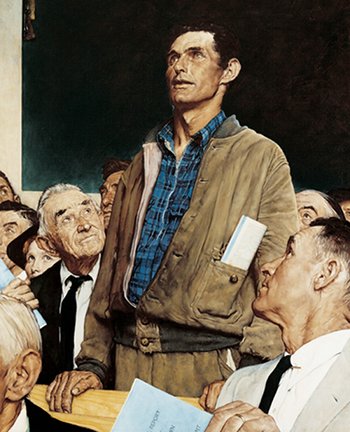

Be a Leader

Remember, most folks quickly congeal into a mass of conformity when crisis strikes. They simply follow the herd, even to their detriment. And they’re easily led by someone who tells them what to do and where to go. Humans are predisposed to obey authority; they’ll follow anyone who seems credible. “It was a very strange phenomenon,” says retired New York City firefighter Jim Cline. “People will follow you, even when they don’t know why they’re following you.”

Now this can be a scary part of human nature, because it means that wolves, sometimes in sheep’s, or more accurately, sheepdog’s clothing, can direct people down a very bad path.

But it also means that true sheepdogs are absolutely vital – both to protect the sheep and to keep these wolves-in-disguise at bay and prevent them from luring the sheep into danger. Grossman defines true sheepdogs as those who not only have the capacity to lead, but do so in harmony with an inner moral compass that compels them to act for the good of the flock.

In times of crisis, when there is no leader, people become paralyzed by inaction, endlessly milling about and asking each other, “What should we do?” Studies have shown that groups that had leaders in a disaster were more likely to survive than groups that didn’t. For example, one study by the U.S. government that looked at three different mine fires found that the commonality among the eight groups that were able to escape was that each had a clear leader.

When it comes to leadership during a crisis, sheepdogs share a few things in common. First, they don’t bully their way into power; they earn the respect of others by their decisiveness, knowledge, and calmness. Second, like real-life sheepdogs, human sheepdogs aren’t afraid to bark at sheep-people if it means lives will be saved. In other words, sometimes you have to forsake niceties in order to save lives.

Airlines have spent a lot of time and money trying to figure out how to get more people off a plane after it crash lands. As we discussed in our previous post, normalcy bias causes most people in a plane crash to remain placidly in their seats. And even those who do get up have a tendency to look for their carry-on luggage before heading towards the exit! Then, when they finally reach the exit, they often pause indecisively for a long period of time before jumping to safety. Yet time is of the essence. You typically have about 90 seconds to get out of a downed plane safely, so there’s no time for lollygagging.

Aviation experts have found that by simply having a flight attendant (or some other person) stand at the exit and aggressively yell at people to move and jump, escape times decreased. The key is aggressiveness. These same researchers found that if flight attendants acted politely during evacuations, “they might as well not have been there at all,” meaning escape times increased.

Rescue workers tasked with saving people from a body of water will often bark at victims before getting to them. They’ve found that if they don’t, victims have a tendency to grab the rescuer and pull them under the water. Firefighters in Kansas City will often yell profanity-laced threats as they approach a victim in order to get their attention and so they don’t drag the rescuer down. Captain Larry Young says, “I hope I don’t offend you by saying this. But if I approach Mrs. Suburban Housewife and say, ‘When I get to you, do not f***ing touch me! I will leave you if you touch me!’ she tends to listen.”

Bottom line, if you want to be a sheepdog, you can’t be afraid to take the lead like Walter Bailey did at the Beverly Hills Supper Club and you can’t be afraid to get aggressive and bark at others. So if you’re a quintessential “Nice Guy,” the time to start working on your assertiveness is now; if you can’t tell your boss you can’t work this weekend, you’re sure as hell not going to be able to tell people to get out of a building. Practice being assertive in little things, so you have the confidence to be aggressive with big things.

Sure, some people won’t like you telling them what to do and will even resent you for it, but that’s to be expected. As Grossman says, “the sheep generally do not like the sheepdog. He looks a lot like the wolf. He has fangs and the capacity for violence. ” Rubbing a few folks the wrong way is a small price to pay to preserve the safety of the flock.

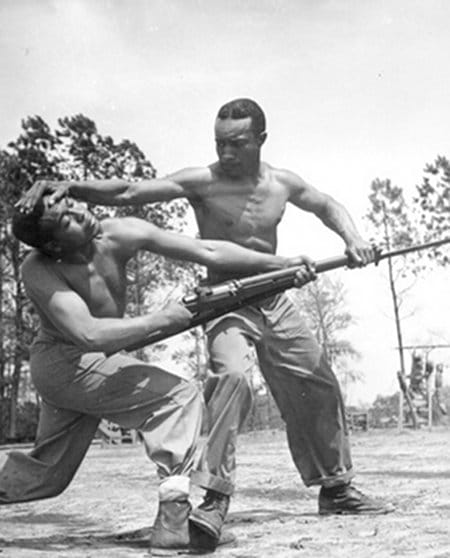

Train Hard

“The more you sweat in training, the less you bleed in battle.”

The most important thing you can do to overcome your sheep-like tendencies is to train them out of yourself. At least that’s what all the research on surviving combat and disaster scenarios tells us. It’s typically the people who trained and prepared for those events that survived and thrived.

To overcome the normalcy bias, you need to repeatedly train yourself to instinctively respond to dangerous situations. Training also inoculates you to the deleterious effects of stress that come with high-stakes scenarios.

There’s a saying amongst soldiers: “you do not rise to the occasion in combat, you sink to the level of training.” You can’t expect to magically perform in high-threat scenarios if you’ve never practiced for them. Moreover, when you do practice, it needs to be regimented and deliberate. You can’t half-ass it.

If you decide to own a handgun, make the commitment to learn how to use it safely and effectively every day. Attend classes taught by professionals; do your daily 20 minutes of focused dry fire so that handling your gun becomes second nature; make it to the range at least once a week for live fire training.

To ensure that your family (and business, for that matter) survives a tornado or fire, routinely have practice drills on what to do in those situations.

If you want to be able to help injured victims, regularly practice first aid skills.

If you want to be able to do the right thing when you notice an ethical wolf wreaking havoc in your company or community, role-play with your friends and colleagues on what you would do in various scenarios.

The day you commit to become a sheepdog, you also make the commitment to keep your warrior’s edge constantly sharp. There’s no time for periods of slacking off. The moment you stop training is the moment your skills begin to decline.

Mentally Rehearse

In addition to regular physical training, researchers and combat experts are discovering that mental rehearsal is a vital part of success in high-conflict and dangerous scenarios. High performance athletes have known for decades the power of visualization exercises. Research has shown that athletes who regularly take part in intense visual imagery exercises perform better than athletes who don’t. It’s only recently that military and police forces have begun to apply this technique to combat and emergency situations.

Emerging research shows that warriors who take part in visual exercises display better marksmanship than those who don’t. There’s also evidence that visualizing successful management of high-stress situations reduces a combatant’s anxiety and stress response when the events actually occur.

Research has also shown that individuals trained in CPR who regularly visualize having to perform the technique respond faster to actual emergencies than individuals who just received the regular training. Not only that, individuals who regularly visualized performing CPR did the technique more correctly than individuals who didn’t practice visualization.

I plan on devoting an entire post to how to use visualization to boost your performance in a variety of situations — not just tactical or survivor scenarios — in a few weeks. Until then, here’s a brief rundown on how to use visualization to prepare yourself for life or death situations:

- Make the visualization as vivid as possible. Incorporate all your senses and emotions.

- Visualize problems and sticking points, but — and this is the critical part — always visualize yourself successfully overcoming the problem or obstacle. Never visualize failure.

- Never rely on visualization alone. It’s important to combine it with tactical practice and role playing.

A few example scenarios you can use during your visualization exercise:

- Visualize what you would do in a severe bleeding scenario. Vividly see yourself performing the requisite steps to successfully treat the victim.

- If you’re taking a defensive handgun class, visualize a live shooter situation. Are there instances when you would or wouldn’t draw your gun? If you do draw your gun, visualize yourself successfully overcoming gun jams and other problems you might encounter. Always visualize yourself winning the fight.

- To prepare yourself for becoming a whistleblower, visualize yourself finding incriminating evidence. Visualize yourself talking to the authorities; visualize the consequences of that decision — job loss, media scrutiny, etc. — but visualize yourself successfully managing and overcoming that stress and anxiety. Visualize the emotions and personal satisfaction of knowing you did the right thing.

- Visualize what you would do in a plane crash. See yourself immediately grabbing your loved ones and heading towards the nearest exit. Don’t forget to imagine the smoke and flames that will likely surround you.

Build Your Resilience

When you decide to become a sheepdog, you accept the responsibility of running towards danger when others flee. A natural consequence of this responsibility is that you’re going to encounter potentially traumatizing events that can break your will to survive and thrive. While training, role-playing, and visualization can help give you confidence and inoculate you from stress, if you don’t have that iron will to keep going even when the chips are stacked against you, you can’t call yourself a sheepdog.

Research on survivors and professional sheepdogs shows that they tend to be a resilient bunch, some naturally so. While genetics plays a role in how resilient we are, we can actually strengthen our resilience through concerted effort.

A few years ago, we devoted an entire series of blog posts to how to increase your resilience. They’re all based on the latest psychological research. I recommend that you read through them and put the suggestions into practice. For a more in-depth look on how to boost your resilience, read the following books:

- Resiliency Advantage by Dr. Al Siebert

- The Resilience Factor by Dr. Karen Reivich and Dr. Andrew Shatte

- Undefeated Mind by Alex Lickerman

- Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges by Steven M. Southwick and Dennis S. Charney

- Learned Optimism by Martin E. P. Seligman

Develop Your Intuition

“Technology is not going to save us. Our computers, our tools, our machines are not enough. We have to rely on our intuition, our true being.” —Joseph Campbell

For us men, intuition is one of those touchy-feely concepts that we typically associate with women. As Gavin de Becker explains, men “much prefer logic, the grounded, explainable, unemotional thought process that ends in a supportable conclusion.” But to become a truly effective warrior or sheepdog, you need to become more intuitive and instinctual.

According to psychologist Daniel Kahneman, our minds have two systems or ways of thinking. First, there’s slow thinking. That’s the type of thinking that we’re most familiar with. It’s what we use when we do math, make logical arguments, or deliberate a decision with facts and figures. Fast thinking, on the other hand, is subconscious, automatic, and emotional. Kahneman calls this type of thinking “System 1.” A better name for it would be intuition.

While our intuition can certainly steer us in the wrong direction, if properly trained and relied upon in certain contexts, it can save your life or the lives of those around you. That’s the premise of de Becker’s book, The Gift of Fear, a book I highly recommend you read.

It’s interesting to note that the root of the word intuition, tuere, means “to guard, to protect.” How appropriate for a sheepdog.

Take up a Martial Art/Combat Sport

Sheepdogs, unlike sheep, have a propensity for violence – they just channel that capacity towards honorable ends. Sheepdogs must be capable and willing to use force to eliminate or at least subdue a threat. But as Grossman thoroughly explained in his book, On Killing, most humans (at least of the modern, civilized variety) have a natural repulsion to kill or even engage in conflict, be it physical or verbal.

I was talking to a gentleman at church a few months ago who is probably in his early 70s. Somehow fighting came up and he mentioned that he’s never been in a fistfight in his entire life. It’s not that he tried to avoid them; the opportunity just never presented itself. The great majority of men in America are in the same situation; they’ve never punched another man, nor know what it feels like to be punched. They’ve never grappled with another man, or been put in a headlock and experienced the surge of fear and adrenaline of being locked in hand-to hand combat. This doesn’t prevent the average man from imagining how he’d totally kick ass if the opportunity did present itself, of course, but if the experience of being in a physical fight is completely foreign to you, you won’t automatically know what to do when you find yourself in one. This is a specific area where it’s particularly important to train before the moment comes.

Develop Your Capacity to Love

Sociologist and holocaust survivor Samuel Oliner has spent his career studying what causes some people to go to the aid of their fellow man. His research found that heroes have a few things in common. First, rescuers tend to have had healthier and closer relationships with their parents. Second, they’re more likely to have friends of different religions and classes. Third, and most importantly, heroes are empathetic.

While the sheepdog and wolf both have a propensity for violence, what separates them is that the sheepdog has a deep and abiding love for the sheep he watches over. Thus, while you’re training to use violence, you must simultaneously train to love.

How do you do this?

First, it’s important that you develop your empathy. Teddy Roosevelt called empathy “fellow-feeling.” It’s that ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and see and feel how they see and feel. As the great Atticus Finch put it, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view — until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” It’s hard to show love towards someone that you can’t empathize with. To gain empathy, you have to step away from your screen, and from solely interacting with fellow humans as disembodied selves. The more we rub shoulders with people in the flesh, the more fellow-feeling we develop for them. This feeling is heightened through service, especially to those who are different than us. The leadership of a sheepdog is that of a servant leader — so volunteer, become a mentor, and look for opportunities to serve in your day-to-day life. As you serve, you will come to love your flock.

Get in Shape

Being physically fit gives you two big advantages in a high-conflict/high-stress situation. First, the man who is physically strong has a strength and endurance advantage over the man who doesn’t. All fights aren’t gunfights. Do you have the strength and endurance to successfully win in hand-to-hand combat? Could you chase down a purse snatcher? Lift debris off another person? Carry someone to safety? Could you even save your own life?

Second, and more importantly, physically fit men handle stress better than their less fit counterparts. “Overall stress tolerance is great in well-conditioned individuals,” says Grossman and “they demonstrate a more stable mood,” as well as “show a clearer mental functioning under stress.” As we’ve discussed before, our physical and mental abilities begin to deteriorate in high-stress situations. However, it is possible to train our minds and bodies to continue to perform despite high levels of stress. Skill training and visualization are important pieces of this puzzle; fitness training is the third.

If you haven’t started a regular workout routine, but fancy yourself a sheepdog, make the commitment to start exercising today. We’ve laid out several workouts on the site over the years. Pick one that appeals to you and do it. I’ve always found it helpful to have some sort of goal or benchmark to work towards in order to stay motivated for exercise. Make it your goal to be able to pass the WWII military fitness test or fulfill the benchmarks old-time strongman Earle Liederman argued were proof a man could save his own life.

Nip Dishonesty and Unethical Practices in the Bud

While Grossman concentrates his discussion of the role of the sheepdog in physically confronting wolves, I think a true sheepdog is equally prepared to deal with wolves that weaken the fabric of society through dishonest and deceitful practices. He’s willing to stand up, be a whistleblower, and stop sheep from being fleeced. While it’s easier to imagine training for a combat or disaster situation, you can train yourself to be an ethical sheepdog too.

Grossman argues that only around 1% of the population are true wolves – real sociopaths – and psychologist Dan Ariely interestingly found this to be true when conducting experiments on cheating. Even when given the opportunity to cheat, and offered a financial reward for doing so without any consequences or chance of being caught, very few participants in his experiments cheated to the full extent possible. And yet most people still cheated – just by a little bit. For example, when given math puzzles to solve, offered a few dollars for each one they got correct, and allowed to self-report their performance, participants on average reported solving two more problems correctly than they really did. Ariely calls this the “fudge factor theory” – people want to gain financially, but they also want to be able to keep seeing themselves as good, honest people. They solve the dilemma by cheating just a little — enough to get an advantage, but not so much that it affects their positive self-image.

The problem with these little dishonest acts is that they can lead to a domino effect that poisons the ethics of a whole culture. Ariely found that the more someone cheated, the more likely they were to reach an “honesty threshold,” the point in which they became subject to the “what-the-hell effect” in which they would think, “What the hell, as long as I’m a cheater, I might as well get the most out of it.” They went from cheating a little, to throwing caution to the wind and cheating at every opportunity they could during the experiment. Ariely also found that dishonesty can spread like an infection through groups; because we look to each other to see what’s socially appropriate, when we see someone else cheating, we’re more inclined to do it too. His experiments led him to conclude that the best way to curtail unethical behavior in society is by nipping it in the bud while it’s still small and emerging:

“The bottom line is that we should not view a single act of dishonesty as just one petty act. We tend to forgive people for their first offense with the idea that it is just the first time and everyone makes mistakes. And although this may be true, we should also realize that the first act of dishonesty might be particularly important in shaping the way a person looks at himself and his actions from that point on—and because of that, the first dishonest act is the most important one to prevent. That is why it is important to cut down on the number of seemingly innocuous singular acts of dishonesty. If we do, society might become more honest and less corrupt over time…

Passed from person to person, dishonesty has a slow, creeping, socially corrosive effect. As the ‘virus’ mutates and speeds from one person to another, a new, less ethical code of conduct develops. And though it is subtle and gradual, the final outcome can be disastrous. This is the real cost of minor instances of cheating and the reason we need to be more vigilant in our efforts to curb even small infractions.”

To train to become an ethical sheepdog, practice integrity even in the small things – telling the cashier that they gave you too much change or fighting the temptation to offer a lie to excuse your tardiness. Setting an example of honesty will encourage others to act honorably too.

Ariely has also found that cheating greatly diminishes when people know they are being observed. That’s why it’s so important to have sheepdogs who are alert and aware (see below) and are willing to speak out even when small moral and ethical standards have been violated. Again, this may not make the sheepdog popular – people don’t like a “narc.” But the sheepdog’s role is to stop the “infection” before it slowly spreads and weakens the flock.

Semper Vigilantissimi

Semper vigilantissimi. Always vigilant. Real-life sheepdogs are constantly on the lookout for threats. They’re always scanning their environment and investigating if things don’t seem right. If you wish to be a human sheepdog, you must be equally vigilant. You should always be in a “relaxed alert” frame of mind, or what defense expert Jeff Cooper calls “Condition Yellow.” When you’re in Condition Yellow, no specific threat exists and you’re not paranoid about nonexistent threats. You’re simply aware that the world is a potentially dangerous and unfriendly place and you’re ready to defend yourself or take action to assist others. When you’re in Condition Yellow, you’re constantly taking in information about your surroundings in a relaxed but alert manner. You’re what tactical experts call “situationally aware.”

Conclusion

As I mentioned at the outset of the post, there’s no way that I could cover everything a man needs to know in order to become a sheepdog in a single article. As you can see, even laying out these general principles has taken up quite a bit of space! However, I hope that this post has provided you with a roadmap on what you need to do in order to overcome your natural sheepishness. I know many of you are hungry for more details on many of these concepts, but I hope you will believe me when I say they’re each worth an in-depth post of their own. I’m really excited about revisiting them in the coming months and hope you are too. Here are some of the subjects we will be taking up in-depth this year, in addition to continuing our usual sheepdog-related articles on things like gunmanship, first aid, fitness, self-defense, and survival:

- How to Develop Your Intuition

- How to Inoculate Yourself Against Stress

- How to Use Immersive Visualization

- How to Develop Situational Awareness

- Levels of Awareness

- Hack Your Mind Like a Twenty-First Century Soldier

- How to Increase Your Personal Integrity and the Foster Integrity in Society

- The Sheepdog Library (the best books on developing into a sheepdog)

Any other skills and mindsets you think I should cover in the future? Please let me know in the comments!

______________________________________

Sources:

On Killing by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman

The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes – And Why by Amanda Ripley

Warrior Mindset by Dr. Michael Asken, Loren W. Christensen, Dave Grossman and Human Factor Research

On Combat by Dave Grossman and Loren W. Christensen

The Survivors Club: The Secrets and Science that Could Save Your Life by Ben Sherwood

The Gift of Fear by Gavin de Becker

The Honest Truth About Dishonesty–How We Lie to Everyone, Especially Ourselves by Dan Ariely

Tags: Self-Defense & Fighting