In case you’ve forgotten, Halloween is this Wednesday. With all the ghosts and goblins decorating homes these days, I figured it’s a great time to talk about one of my favorite genres of art: memento mori.

Memento mori is Latin for “Remember death.” The phrase is believed to originate from an ancient Roman tradition in which a servant would be tasked with standing behind a victorious general as he paraded though town. As the general basked in the glory of the cheering crowds, the servant would whisper in the general’s ear: “Respice post te! Hominem te esse memento! Memento mori!” = “Look behind you! Remember that you are but a man! Remember that you will die!”

Memento mori. Remember that you will die.

Us moderns don’t like to think too much about death. It’s a bit too depressing and morbid for our think-positive sensibilities. Our culture is devoted to perpetuating the lie that you can stay young forever and your life will go on and on.

But for men living in antiquity all the way up until the beginning of the 20th century, rather than being a downer, death was seen as a motivator to live a good, meaningful, and virtuous life. To help men remember death, artists created paintings, sculptures, and mosaics depicting skulls, skeletons, and other symbols of death. Churches would display memento mori art to compel viewers to meditate on death, reflect on their lives, and re-dedicate themselves to preparing to meet God. Devout Christians would often ask that their tomb or grave marker have some sort of skeleton motif on it to remind their visiting family members to get right with God before they too bit the dust.

Below, I’ve put together a collection of famous memento mori artwork. Not only would these paintings of skulls and skeletons look badass hanging in your home, they can also help remind you that you’re dying daily, encourage you to quit wasting your life away on stupid stuff, and motivate you to start living the life you want NOW.

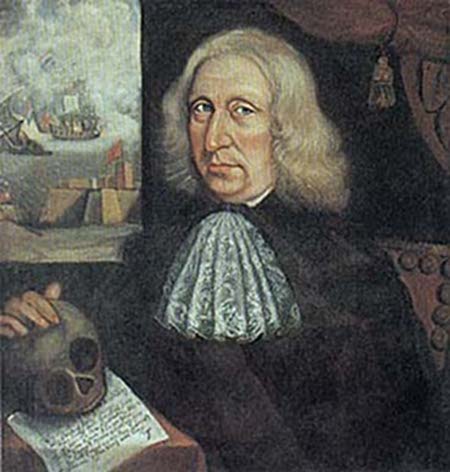

Self Portrait by Thomas Smith, 1680

Memento mori woodcut by Alexander Mair, 1605

In ictu oculi by Juan de Valdés Leal, 1672

Saint Jerome by Albrecht Dürer, 1521

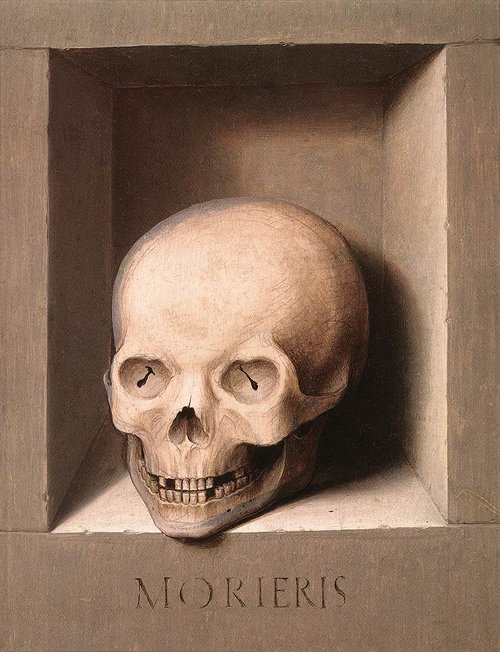

Morieris by Hans Memling, 1483

Unnamed illustration by Mary S. Gove, 1842

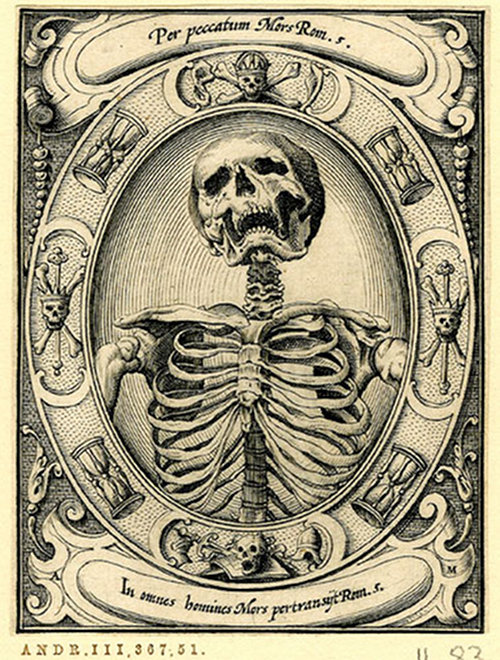

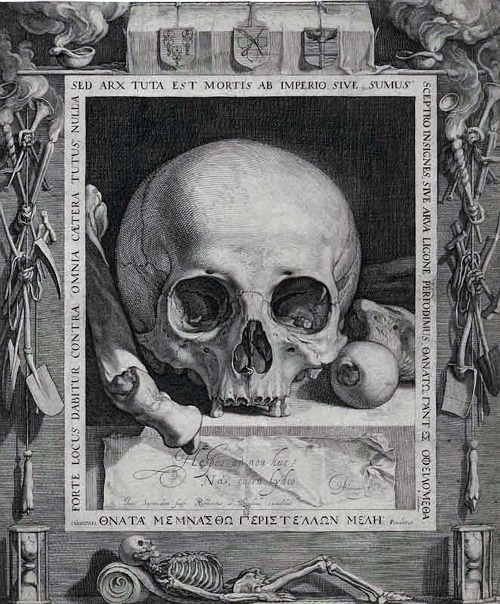

Memento Mori by Jan Saenredam, late 16th century

Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull by Frans Hals, 1615

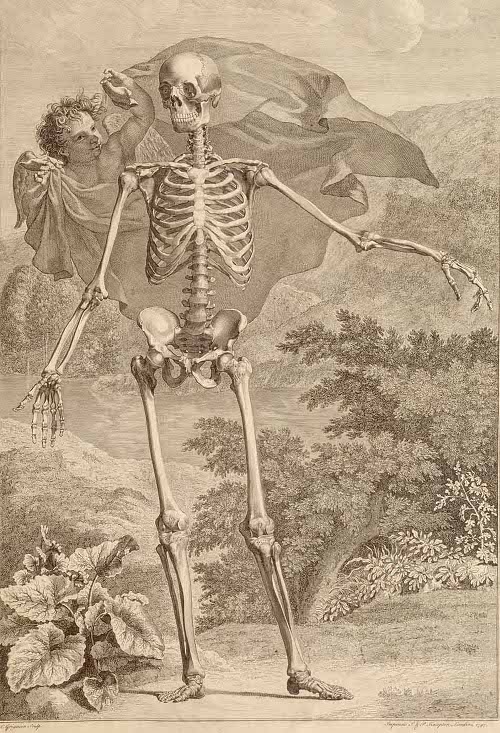

sceleti et musculorum corporis humani by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, 1749. Albinus was an anatomist who would often depict human skeletons in traditional memento mori motifs.

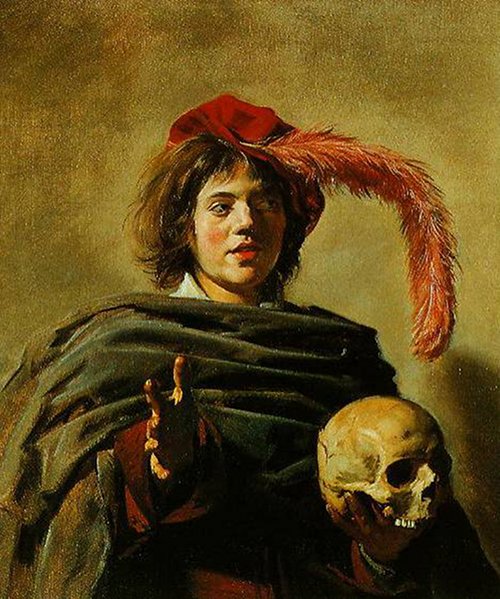

Young Man Holding a Skull by Frans Hals, 1626.

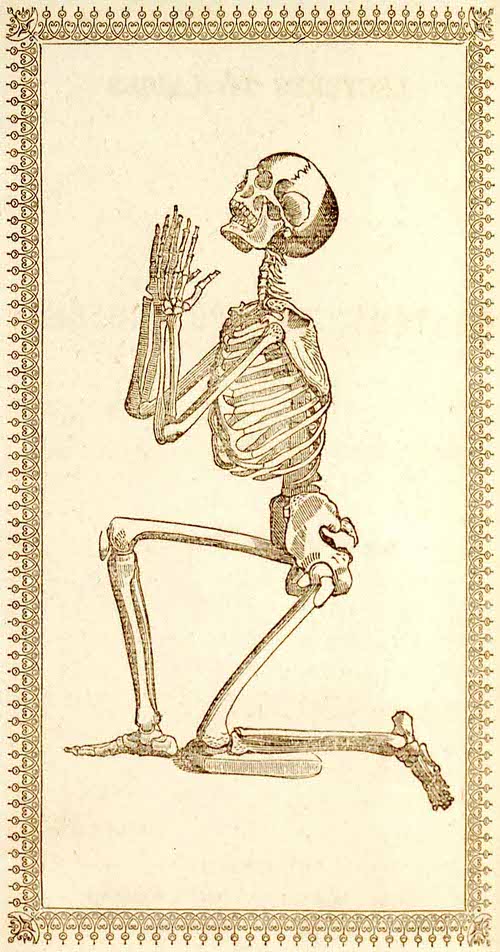

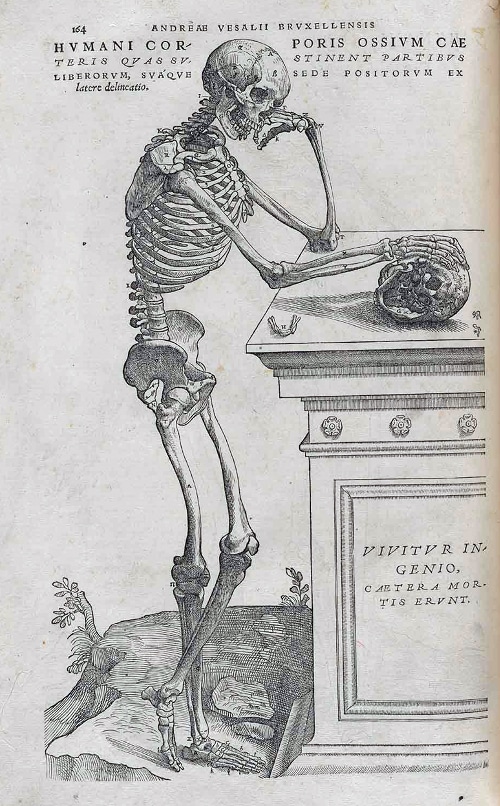

Unnamed illustration by Andreas Vesalius, 1543. Vesalius is considered the founder of modern anatomy and published the first comprehensive anatomy book of the modern era: “De humani corporis fabrica.” This illustration is an obvious play on memento mori motifs. It’s actually kind of meta. Death mediating on death.

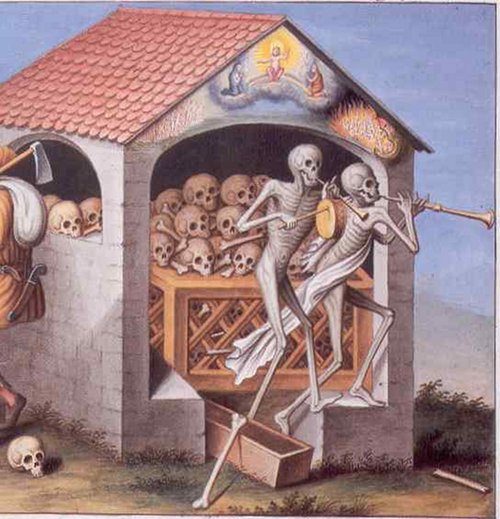

Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death

The Dance of Death by Michael Wolgemut, 1493

A sub-genre of memento mori art is Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death. This genre of art has its origins in late medieval times but became popular during the Renaissance. Dance of Death paintings typically portray a skeleton (signifying Death or the Grim Reaper) walking, dancing, or playing music. To convey the universality of death, people from all walks of life — kings, popes, peasants, and children — are invited by jovial skeletons to follow them in a dance to the grave. Dance of Death art (and it also took the form of plays and poems), grew out of the grim horrors of the 14th century: famine, the Hundred Years War, and, most of all, the Black Death. The latter starkly demonstrated the way in which death united all, felling the population without the faintest regard for age or rank.

Some Dance of Death paintings are rather morbid, graphic, and downright creepy. Whether or not it gives you the heebee jeebees, there’s no denying its powerful reminder that we’ll all have to pay the fiddler once our mortal hoedown is through.

Dance of Death by Emmanuel Büchel, 1773

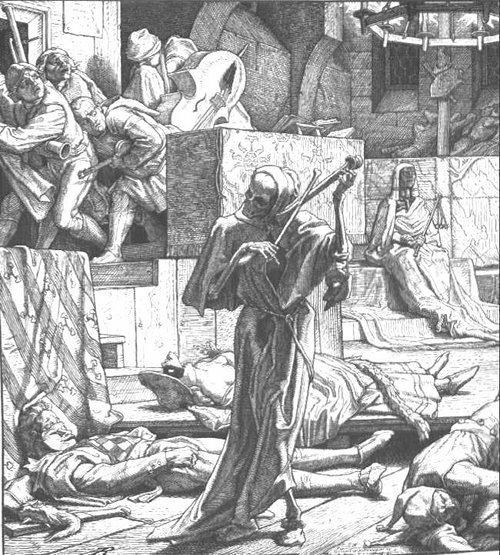

Death as a cutthroat by Alfred Rethel, 1851. Rethel was inspired by an account of how an outbreak of cholera ravaged a masquerade during the Carnival of Paris in 1832.

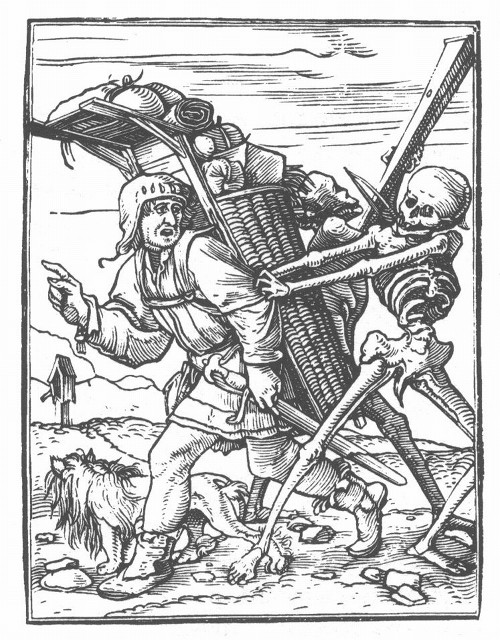

Dance of Death. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523-1526. This woodcut is part of a series Holbein did on the Dance of Death theme.

Unnamed illustration by unknown author, 1488. This image (and the 3 below) comes from a series of late 15th century woodcuts based on the Dance of Death theme. The book that contained these woodcut images was entitled Heidelberger Totentanz. Scholars believe it was the first collection of art dedicated solely to the Dance of Death theme.

This appears to be a king accompanied by a trombone-playing skeleton.

Sadly, as people in antiquity knew all too well, even children sometimes can’t escape the dance with death.

Life is often a game of chance. Fortunes come and fortunes go. But we all have to cash out and head to the big casino in the sky.

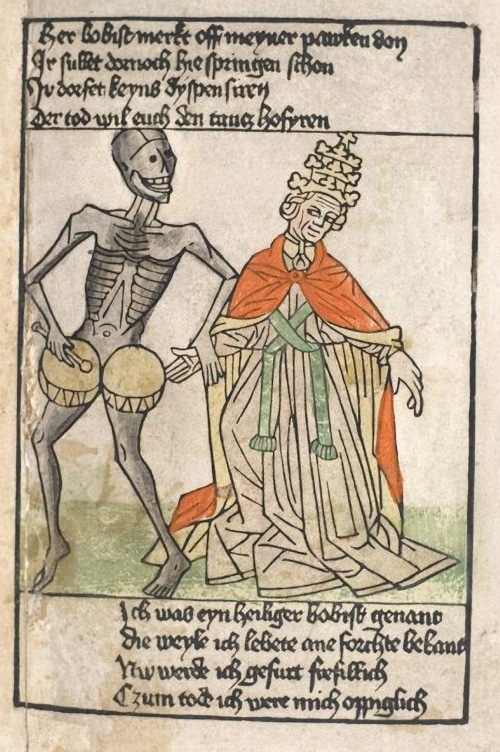

Heidelberger Bilderkatechismus, 1455. This is possibly one of the earliest depictions of the Dance of Death. That king kind of looks happy to be hanging out with Death. But I guess if the Grim Reaper had to come, at least he came playing the drums.

The 13th century legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead was a popular theme of murals and frescoes. In the legend, three gentlemen or kings meet the cadavers of their ancestors, who warn them: “Quod fuimus, estis; quod sumus, vos eritis” (What we were, you are; what we are, you will be!).

Vanitas Vanitatum Omnia Vanitas

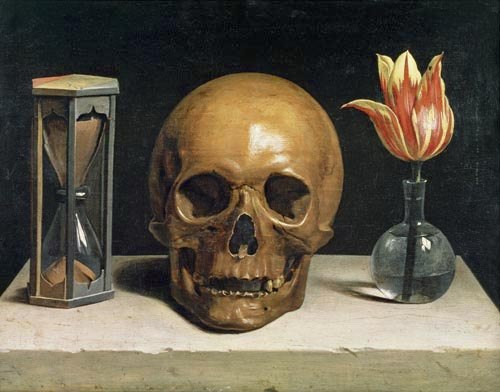

Still Life with a Skull by Philippe de Champaigne, 1671. The three essentials of existence: life, death, and time.

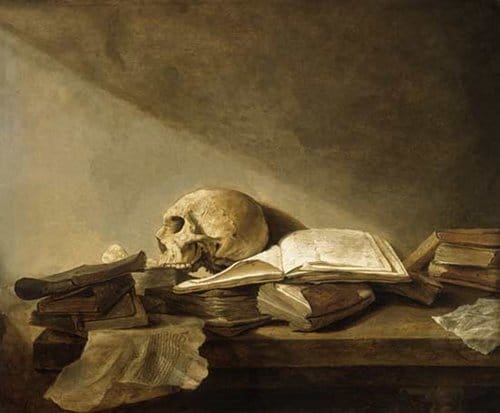

Another sub-genre of memento mori art is called vanitas. This artistic motif was particularly popular among Dutch Golden Age artists of the 16th and 17th centuries. The famous passage from chapter 1 of Ecclesiastes on the fleeting and impermanent nature of our mortal life is cited as the inspiration for this morbid art.

2 Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

3 What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?

4 One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.

5 The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

6 The wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits.

7 All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

8 All things are full of labour; man cannot utter it: the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.

9 The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.

10 Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us.

11 There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after.

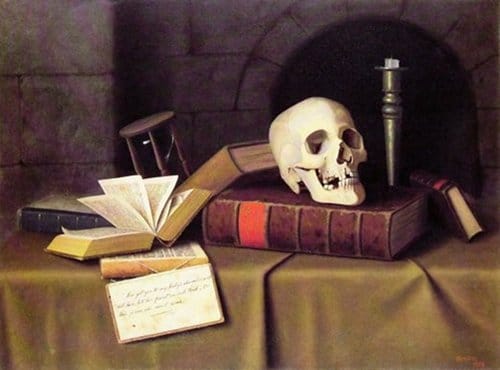

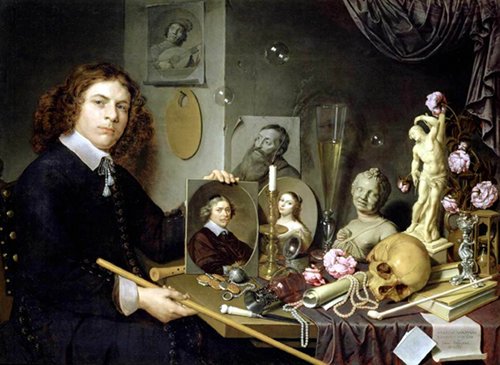

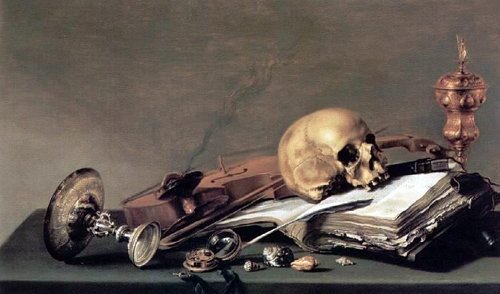

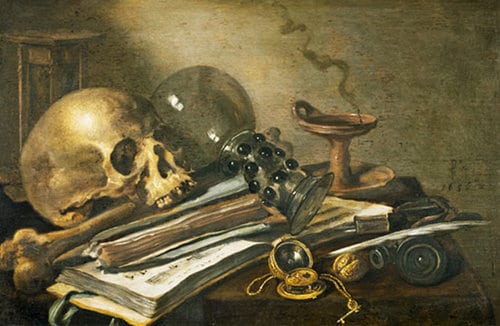

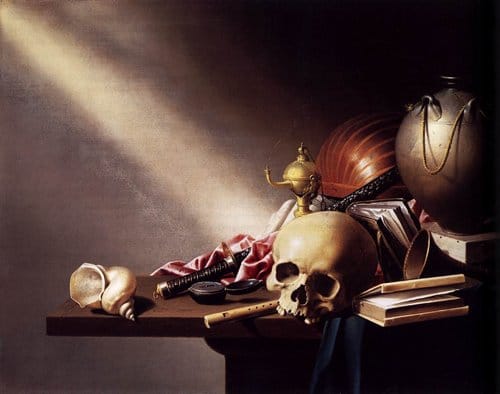

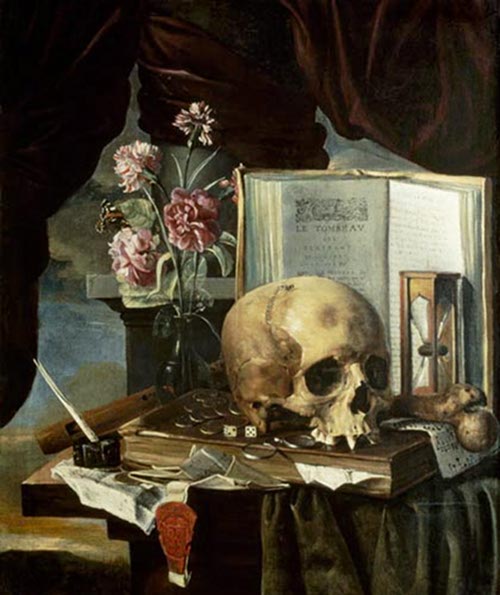

In vanitas art, the certainty of death and our mortality are still the main themes, but there’s an added emphasis on the fleetingness and insignificance of earthly glory and pleasures. Common symbols in vanitas art include the skull (representing the certainty of death); bubbles (representing the brevity and fragility of life and earthly glory); smoke, hourglasses, and watches (every minute that passes brings you closer to death); rotting fruit and flowers (representing the fragility and decay of earthly things); musical instruments and music sheets (representing the ephemeral nature of life); torn or loose books (representing earthly knowledge); and dice and playing cards (representing the role that chance and fortune play in life).

The purpose of vanitas art is moral instruction. It’s to remind the viewer that life is precious, so they better not waste it on frivolous and meaningless things.

Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols by David Bailly, 1651. Notice the bubbles.

Vanitas Still Life by Jacques de Gheyn the Elder, 1603. Notice all the vanitas symbols: skull, bubble, smoke, and flower. Money seems to be another symbol in this painting. It likely represents the foolishness of “laying up your treasures where moth and dust doth corrupt.”

Vanitas Still Life by Jan Davidsz de Heem, 17th century

Vanitas Still Life by Jan Davidsz de Heem, 17th century.

Vanitas Quiet Life by Pieter Claesz, early 17th century. Which vanitas symbols can you see?

Vanitas Still Life by Simon Renard de Saint-André, middle of the 17th century.

Still Life, An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life by Harmen Steenwijck, 1640.

Vanitas Still Life by Simon Renard de Saint-André, middle of the 17th century. Notice the hourglass, pair of dice, and sheet of music.

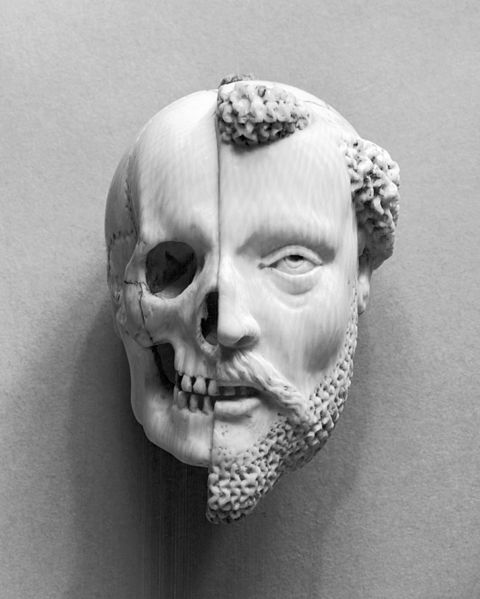

Memento mori themes were common in mediums beyond paintings as well, such as this 16th/17th century ivory pendant: Monk and Death. I like this one, because Kate often says to me, “Whoa, you have a skeleton under there.” Whoa indeed.

I know death isn’t the most pleasant thing to think about, but today I challenge you to pick out one of the memento moris above and really study it. Think about the symbols and what they mean. As you do so, ask yourself: Am I dedicating my life primarily to activities and things that will simply fade away like smoke and bubbles? Or I am making the most of my life by creating a legacy that will live beyond the grave?

Memento mori, gentlemen.