Welcome back to our series on the history of the American bachelor. In Part I of the series, we took a look at the bachelor during colonial and Revolutionary War America. In Part II, we discussed the emergence of a distinct bachelor culture at the turn of the 20th century. Today, we’ll jump ahead to describing the position of the bachelor at mid-century, as well as take a look at the state of the American bachelor today.

Post-WWII America: The Bachelor Settles Down

As we discussed in our last segment, the bachelor population swelled in America in the decades after the Civil War. In many large cities, more than 50% of the adult male population was single. Moreover, young men began putting off marriage. In 1890, the average marrying age for men peaked at 26.

After the bachelor boom of the late 19th century, the median marriage age for men and the proportion of all adult males who were unmarried began to decline slowly and eventually leveled out during the Great Depression. In 1930, the average marrying age for American men was 24; 41.7% of the male population was single.

During both World Wars, the United States used conscription and relied primarily on bachelors to quickly raise their troop levels. While both single and married men were required to register for the draft, married men with dependents were sometimes given deferments, while single men shipped out.

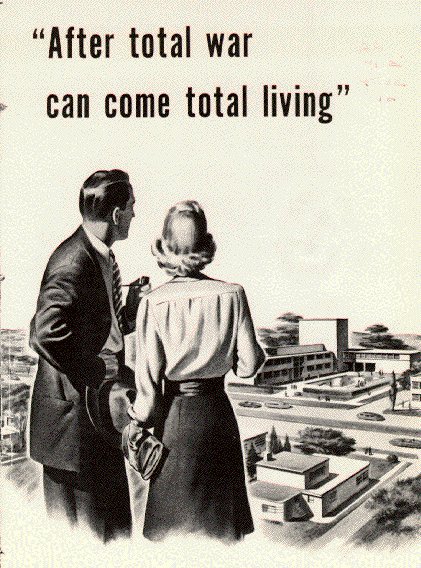

Before heading off to war, young GIs often decided to tie the knot with their girlfriends, ensuring they’d have love and support from the home front and someone to look forward to coming back to. Once the war was over, the men who returned still single had had their fill of violence, deprivation, and living in an all-male environment, and were more than ready to trade their ditches and cots for the tranquility and domestic comforts of hearth and home, along with the touch (and delicious meatloaf) of a woman.

And economic conditions after the war were ideal for fulfilling those desires. While the rest of the world recovered from the ravages of war, the United States entered a period of unprecedented prosperity and became an industrial powerhouse. Jobs were plentiful and paid well, and thanks to the GI Bill–which defrayed the costs of going to college, offered loans to those who wished to start a business or farm, and provided low mortgage rates to veterans–the dream of education, homeownership, and a comfortable life became accessible to millions of men.

This newfound prosperity made marriage and family life possible for post-WWII men much earlier in their adult lives than their 19th and even early 20th century counterparts. Thus the average marrying age and the population’s percentage of single men began a sharp decline in 1949. That year, the average marrying age dipped to 23–the lowest since the Census had begun tracking this statistic back in the 1880s.

During the 1950s, family life took center stage in America. Settling down, buying a house in the suburbs, and having kids was seen as the patriotic thing to do. Television shows and movies during the 1950s portrayed family life in an idyllic fashion–mom vacuuming and wearing pearls, dad coming home from work to piddle around in the yard or his workshop, and the kids getting into mischief.

Meanwhile, bachelors were often portrayed as social misfits who caused trouble–after all, many thought, if a comfortable family life was so much more accessible than ever before, if you still weren’t settling down, there was probably something wrong with you. Psychologists, social scientists, and clergymen during this period began a public relations campaign against, not only bachelors, but single women as well. In the 1949 book, Why Are You Single? several psychologists and sociologists submitted essays which labeled singledom “unnatural and socially dysfunctional.” Single people were portrayed as maladjusted and in need of fixing. In an essay called “The Marriage-Shyness of the Male,” a Freudian psychologist painted the bachelor as a sort of basket case, battling inner as well as outer demons that prevented him from taking a wife.

The social pressure to marry, along with the lower costs of living, continued to drive down the marriage age and the size of the bachelor population throughout the 1950s. By 1960, only 23% of American men remained single, and the average age men were getting married was about 22. The bachelor had become the family man.

But the state of the bachelor, ever in flux, would soon shift once again.

The Sexual Revolution: A New Bachelor Emerges

The decline of the American bachelor in the 1950s was short lived. Starting in the 1960s, the marriage age and the number of single men began to inch back up. As Baby Boomers came of age during the Sexual Revolution of the late 1960s, American Bachelorhood experienced a revival.

For much of American history, marriage was a prerequisite to sex. Yes, people have had sex out of wedlock since time immemorial. In fact, bachelors sowing their wild oats and corrupting young women was one of the biggest fears society had about single men in the 19th century.

But overall, sex outside of marriage was frowned upon if not privately, then culturally, and those guilty of it suffered a high social penalty, especially if their relations resulted in an out-of-wedlock child. For many men, giving up some of their freedom to get married was the price for regular, safer, and more socially acceptable sex. Thus when the birth control pill made its debut and the taboo of women having casual sex began to lift, many men started to put off marriage. “What’s the point of getting married if I can get sex without it?” bachelors began to ask themselves. A bachelorhood that extended not just through one’s 20s, but one’s 30s and beyond, began to be seen as a viable, and for some, a very desirable, option.

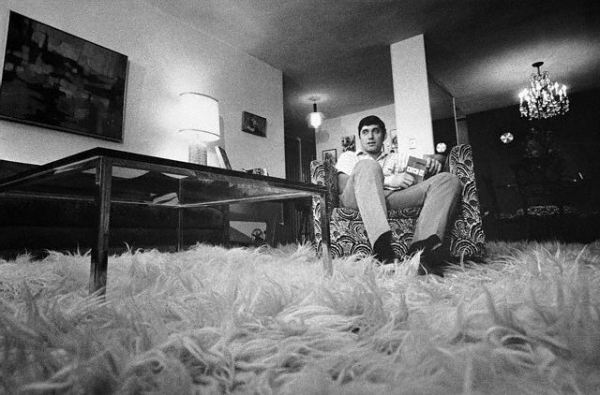

Joe Namath was a paragon of the 60s bachelor ideal: young, virile, rich, lots of girlfriends, and a sweet bachelor pad complete with fluffy carpet.

In addition to the loosening of sexual mores, young Baby Boomer men enjoyed high paying jobs and low-cost homes and apartments that made living alone a viable option for many of them. In fact, living alone became a status symbol for men during the 60s and 70s. The era of the bachelor pad with its swanky and masculine decor began. The new bachelor could date many women, and he needed a swinging place in which to entertain them.

Overseeing (and in many ways directing) this Bachelor Renaissance was a young magazine publisher named Hugh Hefner. In 1953, Hefner started his iconic Playboy magazine (which was initially going to be called Stag Party) that became famous for its nude Playmates and ever-so-well-written articles. Within the pages of Playboy, Hefner created a new kind of bachelorhood. Instead of the sporting male with his blue collar tastes, Hefner promoted a bachelorhood that was more urbane and sophisticated. According to him, a Playboy man was different from the rugged, outdoors-y man promoted in other men’s magazines:

“We like to spend most of our time inside. We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, and sex.”

If the 1950s squashed the idea of the rebellious and independent bachelor that was forged in the 19th century, Hugh Hefner helped resurrect it. His campaign to remove feelings of shame about sex and his unabashed rebellion against societal norms not only earned him powerful enemies, like Richard Nixon and J.Edgar Hoover, but also fans in single men who saw Hef as a hero for the American bachelor. Regardless of how you feel about old Hef yourself, his influence on our cultural conception of the American bachelor is undeniable.

The 21st Century: Marrying Age and Living Arrangements

Today, the average marrying age for American men continues to increase. In 2010, it was 28. Many social commentators wring their hands about this trend, feeling that it represents an unprecedented shift in American history and a cultural decline that began at some point in the shrouded mists of the past. This worry is typically rooted in a comparison (whether the commenter is aware of it or not) between today’s marrying age and what it was in the 1950s and 60s (22 years old).

But if you compare the modern marrying age to the marrying age for men in the 1890s (26 years old), modern men are putting off marriage just two years longer than their great-grandfather’s generation. And if you compare the modern marrying age to all average marrying ages since the beginning of the Republic, the low marrying age and low single population of the 1950s was actually a very short-lived anomaly, made possible by a booming economy and help from Uncle Sam. Now, in this current economic downturn, men are putting marriage off longer.

Of course, I’ve never understood why folks think that they must be financially well-off before marrying; it isn’t any harder to be poor and married than poor and single, and getting hitched when you’re young and broke allows you to grow together, and has much to recommend it in my opinion. But I guess that’s another discussion for another time.

Social commentators have also raised a lot of hubbub about the fact that more and more young, single adults are moving back in with mom and dad or aren’t even heading out on their own at age 18. Magazine articles lambast these young adults for “failing to launch” or pejoratively call them “boomerang kids.” Young, single men seem to get the brunt of this criticism because studies show that the proportion of single men living with their parents has increased much faster than the proportion of single women doing the same.

However, again, if you look at the historical record, the hand wringing and criticism appears to be overblown. In 1860, 60% of young, single men lived with their family. Today, that number is 18.7%. And the percentage of single men living with their parents has only increased 4% since 2007. So while more single men are living with their folks, it isn’t the unprecedented crisis in maturity that the media makes it out to be.

Rather, it is often a move that just makes good financial sense and is part of the reality of our current economic climate. Men in the 1950s could get a good paying job without even having to go to college. Today, young men are emerging from college saddled with huge student loan debt and must navigate an economy with fewer good job prospects. It simply takes longer for young men to get on their feet these days. Certainly some young men are using free accommodations with mom and dad to put off responsibilities and delay their adolescence, but many very much want to get out on their own as soon as possible and are working towards their goal…just like Great-Grandpappy did.

For men for whom moving back in with their parents is not a possibility or something they can stomach, sharing a house or apartment with a bunch of friends is a common option. The percentage of men living with same-sex roommates has been increasing since 2007. In Guyland, Michael Kimmel notes that more and more young, single men are pooling resources to rent fairly decent bachelor pads. They’ll equip their place with big screen TVs and video game consoles, and the atmosphere in these multi-person bachelor pads often feels like a continuation of college life.

Into the 21st Century: Bachelor Culture Morphs to Bro Culture

While bachelorhood has always been a period in a man’s life where he enjoyed the benefits of freedom and independence by taking part in vices and fun that might not be fitting for a family man, there was a general understanding among men that their bachelor years would eventually end and that they needed to use their single years to lay a foundation for the rest of their lives. Drinking and playing pool was balanced by membership in mutual improvement societies and fraternal lodges, and by a general code of behavior among men (see the third paragraph of this Manvotional). Moreover, while bachelorhood became more and more accepted in America, there was an expectation that young, single men still be useful and productive members of society. The bachelor worked hard and played hard.

Today’s young bachelor often doesn’t have that same understanding nor the societal expectations of his predecessors. He also rarely has a group of positive, older male mentors to help balance his masculine desires to act out with some wisdom on how to segue into approaching life more maturely. Diminished expectations towards young, single men, coupled with a more crude, and in many ways less mature notion of masculinity, has resulted in a new, lowest common denominator idea of the bachelor: The Bro.

Like parts of bachelor culture in previous decades, Bro culture encourages drinking, sports, and sex as ways a young man can display his masculinity. The difference is that Bro culture amps it up several notches. The dream of the Bro is that his adolescent-esque life never has to end. Books like Tucker Max’s I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell highlight the bawdy and raucous Bro lifestyle that many young men aspire to today. The internet has spread Bro culture and in many ways shaped it. There are about a dozen websites out there with the word “bro” in the URL: brobible.com, brosome.com, statusbro.com, broslikethissite.com, just to name a few. While many of the sites are tongue-in-cheek and self-aware, the young, male readers of these sites definitely can relate to and find identity with the type of masculinity they highlight.

The replacement of the oldtime bachelor culture with bro culture has a number of deficiencies of course, particularly, for the purposes of this series, as it concerns the effect of bro culture on male camaraderie. While bro culture provides ample opportunities for posses of friends to bond over drinking and carousing, it leaves men who are less interested in such activities with a more difficult time finding a place in a social circle. And bro culture doesn’t travel well. During the “Golden Age of the Bachelor,” a young, single man could move to a new city, easily find the “bachelor district” in town, move into a boarding house or private club with a bunch of guys the same age, meet a bevy of peers at the local pool hall or lodge, and very soon have a new cadre of best buddies. For modern dudes, bro culture works great when they have a group of friends from high school or college to party with, but once they move to a new city where they don’t know a soul, it can be hard to make new friends and assemble a new posse. I believe the modern bachelor oftentimes experiences more loneliness than his turn-of-the-century predecessor did.

The Future of the Bachelor?

Trends indicate that both men and women are marrying less. Only 51% of the adult population today is married. Most experts expect single folks to outnumber marrieds in the next few years–the first time that has happened in America’s history. While co-habitation without marriage has increased over 1500% since the 1960s, according to the Pew Research Center, the number of people choosing the single life (people not forming long-term relationships) has been increasing in the past 10 years as well.

There’s also an interesting trend taking place once you parse the general numbers further. While the percentage of people marrying has fallen for all socioeconomic groups, the decline has been much steeper for the poor and working classes. For college-educated, white collar people, the marriage rate has only declined 11% since 1960; in that same period, the marriage rate for blue collar workers without a college education declined 36%. The divorce rate among the college-educated is much less than the general population as well–just 11%. Thus it is possible that marriage will come to be seen as sort of a privilege and status symbol for the upper classes, which might make endless bachelorhood less sexy–something associated with being lower class.

At any rate, with America’s shifting attitudes towards marriage and the sub-optimal economic conditions in the United States right now, bachelorhood will probably extend further into a man’s adult life for the foreseeable future. Knowing that, perhaps young single men will take a more active role into shaping modern bachelor culture into a period of life that involves something more than drifting along and partying. Already, you see a few signs that this is occurring. Certainly there are some bachelors who have delayed marriage or don’t think they want to get hitched, who are still striving to be productive and well-rounded citizens. Fraternal lodges are seeing a little revival and some college fraternities are actively seeking to return to their roots in balancing having a good time with improving themselves as men. Hopefully the young, single chaps out there will continue this trend!

History of the American Bachelor Series:

Colonial and Revolutionary America

Post-Civil War America

The 20th and 21st Century